(35LK1295), a Site in the Chewaucan Basin of Southeast Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring Wolverines in Northeast Oregon – 2011

Monitoring Wolverines in Northeast Oregon – 2011 Submitted by The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. Title: Monitoring Wolverine in Northeast Oregon – 2011 Authors: Audrey J. Magoun, Patrick Valkenburg, Clinton D. Long, and Judy K. Long Funding and Logistical Support: Dale Pedersen James Short Marsha O’Dell National Park Service Norcross Wildlife Foundation Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Seattle Foundation The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. U.S. Forest Service Wildlife Conservation Society Special thanks to all those individuals who provided observations of wolverines in the Wallowa- Whitman National Forest and other areas in Oregon. We also thank Tim Hiller, Mark Penninger, and Glenn McDonald for their assistance in the field work. This document should be cited as: Magoun, A. J., P. Valkenburg, C. D. Long, and J. K. Long. 2011. Monitoring wolverines in northeast Oregon – 2011. Final Report. The Wolverine Foundation, Inc., Kuna, Idaho, USA. 2 INTRODUCTION The Oregon Conservation Strategy lists “species data gaps” and “research and monitoring needs” for some species where basic information on occurrence and habitat associations are not known (ODFW 2006; pages 367-368). For the Blue Mountains, East Cascades, and West Cascades Ecoregions of Oregon, the Strategy lists wolverine as a species for which status is unknown but habitat may be suitable to support wolverines. ODFW lists the wolverine as Threatened in Oregon and the USFWS has recently placed the species on the candidate list under the federal Endangered Species Act. Wolverine range in the contiguous United States had contracted substantially by the mid-1900s, probably because of high levels of human-caused mortality and very low immigration rates (Aubry et al. -

United States Department of FREMONT - WINEMA Agriculture NATIONAL FORESTS Forest Service Fremont-Winema National Forests Monitoring and August 2010 Evaluation Report

United States Department of FREMONT - WINEMA Agriculture NATIONAL FORESTS Forest Service Fremont-Winema National Forests Monitoring and August 2010 Evaluation Report Fiscal Year 2008 KEY FINDINGS Ecological Restoration: In 2008, the Fremont-Winema National Forests embarked on a 10-year stewardship contract with the Collins Companies’ Fremont Sawmill. This project is aimed at improving environmental conditions in the Lakeview Federal Stewardship Unit, while also supplying material to the sawmill. Under the 10-year stewardship contract, task orders are offered each year to provide forest products in conjunction with restoration service work to reduce fuels and improve watershed conditions. Over the 10 year stewardship contract’s life, at least 3,000 acres per year are projected to be thinned to improve forest health and reduce fuels. The contract is projected to offer at least 10 million board feet of forest products to Fremont Sawmill annually, as well as material for biomass energy. Also on the Forest, two Community Fuels Reduction Projects were completed. The Chiloquin Community Fuels Reduction Project was a 7-year project that reduced hazardous fuels on 1,400 acres within the wild land- urban interface (WUI) around the town of Chiloquin and was the first National Fire Plan project implemented on the Forest. This project was a cooperative effort with the Chiloquin-Agency Lake Rural Fire Protection District, the Klamath Tribes, and community residents. The second project was the Rocky Point Fuels Reduction Project. The Klamath Ranger District, with the assistance of local small business contractors and additional participation by the Bureau of Land Management and U.S. -

Fort Clatsop by Unknown This Photo Shows a Replica of Fort Clatsop, the Modest Structure in Which the Corps of Discovery Spent the Winter of 1805-1806

Fort Clatsop By Unknown This photo shows a replica of Fort Clatsop, the modest structure in which the Corps of Discovery spent the winter of 1805-1806. Probably built of fir and spruce logs, the fort measured only fifty feet by fifty feet, not a lot of space for more than thirty people. Nevertheless, it served its purpose well, offering Expedition members shelter from the incessant rains of the coast and giving them security against the Native peoples in the area. Although the Corps named the fort after the local Indians, they did not fully trust either the Clatsop or the related Chinook people, and kept both at arms length throughout their stay on the coast. The time at Fort Clatsop was well spent by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. The captains caught up on their journal entries and worked on maps of the territory they had traversed since leaving St. Louis in May 1804. Many of the captains’ most important observations about the natural history and Native cultures of the Columbia River region date from this period. Other Expedition members hunted the abundant elk in the area, stood guard over the fort, prepared animal hides, or boiled seawater to make salt, but mostly they bided their time, eagerly anticipating returning east at the first sign of spring. The Corps set off in late March 1806, leaving the fort to Coboway, headman of the Clatsop. In a 1901 letter to writer Eva Emery Dye, a pioneer by the name of Joe Dobbins noted that the remains of Fort Clatsop were still evident in the 1850s, but “not a vestige of the fort was to be seen” when he visited Clatsop Plains in the summer of 1886. -

Radiocarbon Evidence Relating to Northern Great Basin Basketry Chronology

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Radiocarbon Evidence Relating to Northern Great Basin Basketry Chronology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/52v4n8cf Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 20(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Authors Connolly, Thomas J Fowler, Catherine S Cannon, William J Publication Date 1998-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California REPORTS Radiocarbon Evidence Relating ity over a span of nearly 10,000 years (cf. to Northern Great Basin Cressman 1942, 1986; Connolly 1994). Stages Basketry Chronology 1 and 2 are divided at 7,000 years ago, the approximate time of the Mt. Mazama eruption THOMAS J. CONNOLLY which deposited a significant tephra chronologi Oregon State Museum of Anthropology., Univ. of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403. cal marker throughout the region. Stage 3 be CATHERINE S. FOWLER gins after 1,000 years ago,' when traits asso Dept. of Anthropology, Univ. of Nevada, Reno, NV ciated with Northern Paiute basketmaking tradi 89557. tions appear (Adovasio 1986a; Fowler and Daw WILLIAM J. CANNON son 1986; Adovasio and Pedler 1995; Fowler Bureau of Land Management, Lakeview, OR 97630. 1995). During Stage 1, from 11,000 to 7,000 years Adovasio et al. (1986) described Early ago, Adovasio (1986a: 196) asserted that north Holocene basketry from the northern Great ern Great Basin basketry was limited to open Basin as "simple twined and undecorated. " Cressman (1986) reported the presence of and close simple twining with z-twist (slanting decorated basketry during the Early Holo down to the right) wefts. Fort Rock and Spiral cene, which he characterized as a "climax Weft sandals were made (see Cressman [1942] of cultural development'' in the Fort Rock for technical details of sandal types). -

OUTREACH ANNOUNCEMENT USDA Forest Service Wallowa-Whitman National Forest

OUTREACH ANNOUNCEMENT USDA Forest Service Wallowa-Whitman National Forest The Wallowa-Whitman National Forest will soon be filling one permanent fulltime GS-0462-8/9 Lead Forestry Technicians with a duty station in Joseph, Oregon. The vacancy announcement for this position is posted on the U.S. Government’s official website for employment opportunities at www.usajobs.gov. This is a single vacancy announcement. Those that wish to be considered for this position must apply to the vacancy announcement by 11:59 p.m. Eastern Time (ET) on April 5, 2021. This position is being advertised DEMO and anyone can apply. Announcement # (21-R6-11071498-DP-LM) https://www.usajobs.gov/GetJob/ViewDetails/596379100 Position: Lead Forestry Technician (Timber Sale Prep) GS-0462-8/9 Location: Wallowa-Whitman National Forest Joseph, Oregon This notification is being circulated to inform prospective and interested applicants of the following potential opportunities: • Permanent, Competitive Assignment • Permanent, Lateral Reassignment (for current GS-9 employees) Questions about this position should be directed to Noah Wachacha (828-736-2876) or ([email protected]). About the Position The position is established on a Forest Service unit where the incumbent serves as a team leader that performs timber sale preparation duties including timber sale unit layout, timber cruising, timber marking, cruise design as well as preparing contracts and appraisals. The incumbent will be responsible for supervising 1 Permanent PSE Forestry Technician and a 1-2 person (1039) marking crew and will ensure completion of all work required prior to offering timber sales for bid. The Forest encompasses 3 Ranger Districts, the Whitman, La Grande and the Wallowa Mountains Office (WMO) and one National Recreation Area all of which have significant workloads. -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

Vol . 37, No.2 Februory 1975 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES The Ore Bin Published Monthly By STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOlOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Head Office: 1069 Stote Office Bldg., Portland, Oregon - 97201 Telephone, [503) - 229-5580 FIELD OFFICES 2033 First Street 521 N. E. "E" Street Baker 97814 Grants Pass 97526 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Subscription Rate 1 year - $2.00; 3 years - $5.00 Available back issues - $.25 eoch Second closs postage paid at Portland, Oregon GOVERNI NG BOARD R. W . deWeese, Portland, Chairman Willian E. Miller, Bend H. lyle Van Gordon, Grants Pass STATE GEOLOGIST R. E. Corcoran GEOlOGISTS IN CHARGE OF FIELD OFFICES Howard C. Brooks, Baker len Ramp, Gronfl Pass Permiuion il gronted to reprint information contained h..... in. Credit given the State of Oregon D~hMnt of Geology and Min.ollndustries for compiling this information will be appreciated. Sio l e of Oregon The ORE BIN DeporlmentofGeology and Minerollndultries Volume 37, No.2 1069 Siole Office Bldg. February 1975 P«tlond Oregon 97201 GEOLOGY OF HUG POINT STATE PARK NORTHERN OREGON COAST Alan R. Niem Deparhnent of Geology, Oregon State University Hug Point State Park is a strikingly scenic beach and recreational area be tween Cannon Beach and Arch Cape on the northern coast of Oregon (Fig ure 1) . The park is situated just off U.S . Highway 101, 4 miles south of Cannon Beach (Figure 2). It can be reached from Portland via the Sunset Highway (U.S. 26) west toward Seaside, then south. 00 U.S . 101 at Cannon Beach Junction. -

Fort Rock Cave: Assessing the Site’S Potential to Contribute to Ongoing Debates About How and When Humans Colonized the Great Basin

RETURN TO FORT ROCK CAVE: ASSESSING THE SITE’S POTENTIAL TO CONTRIBUTE TO ONGOING DEBATES ABOUT HOW AND WHEN HUMANS COLONIZED THE GREAT BASIN Thomas J. Connolly, Judson Byrd Finley, Geoffrey M. Smith, Dennis L. Jenkins, Pamela E. Endzweig, Brian L. O’Neill, and Paul W. Baxter Oregon’s Fort Rock Cave is iconic in respect to both the archaeology of the northern Great Basin and the history of debate about when the Great Basin was colonized. In 1938, Luther Cressman recovered dozens of sagebrush bark sandals from beneath Mt. Mazama ash that were later radiocarbon dated to between 10,500 and 9350 cal B.P. In 1970, Stephen Bedwell reported finding lithic tools associated with a date of more than 15,000 cal B.P., a date dismissed as unreasonably old by most researchers. Now, with evidence of a nearly 15,000-year-old occupation at the nearby Paisley Five Mile Point Caves, we returned to Fort Rock Cave to evaluate the validity of Bedwell’s claim, assess the stratigraphic integrity of remaining deposits, and determine the potential for future work at the site. Here, we report the results of additional fieldwork at Fort Rock Cave undertaken in 2015 and 2016, which supports the early Holocene occupation, but does not confirm a pre–10,500 cal B.P. human presence. La cueva de Fort Rock en Oregón es icónica por lo que representa para la arqueología de la parte norte de la Gran Cuenca y para la historia del debate sobre la primera ocupación de la Gran Cuenca. En 1938, Luther Cressman recuperó docenas de sandalias de corteza de artemisa debajo de una capa de cenizas del monte Mazama que fueron posteriormente fechadas por radiocarbono entre 10,500 y 9200 cal a.P. -

0205683290.Pdf

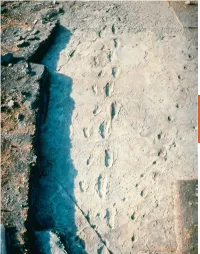

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

Oregon Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Vicki S

State of Oregon Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Vicki S. McConnell, State Geologist USING AIRBORNE THERMAL INFRARED AND LIDAR IMAGERY TO SEARCH FOR GEOTHERMAL ANOMALIES IN OREGON 1 2 3 1 BY IAN P. MADIN , JOHN T. ENGLISH , PAUL A. FERRO , CLARK A. NIEWENDORP 2013 Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries; 2, City of Hillsboro, Oregon; 3, Port of Portland, Oregon OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES, 800 NE OREGON STREET, #28, SUITE 965, PORTLAND, OR 97232 i DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. This product is for informational purposes and may not have been prepared for or be suitable for legal, engineering, or surveying purposes. Users of this information should review or consult the primary data and information sources to ascertain the usability of the information. -

The Chewaucan Cave Cache: the Upper and Lower Chewaucan Marshes

Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 33, No. 1 (2013) | pp. 72–87 The Chewaucan Cave Cache: the Upper and Lower Chewaucan marshes. Warner provided a typed description of the cave location and A Specialized Tool Kit from the collector’s findings; that document is included in the Eastern Oregon museum accession file. He described the cave as being nearly filled to the ceiling with silt, stone, sticks, animal ELIZABETH A. KALLENBACH Museum of Natural and Cultural History bone, and feces. On their first day of excavation, the 1224 University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1224 diggers sifted through fill and basalt rocks from roof fall, finding projectile points, charred animal bone, and The Chewaucan Cave cache, discovered in 1967 by relic pieces of cordage and matting. On the second day, they collectors digging in eastern Oregon, consists of a large discovered the large grass bag. grass bag that contained a number of other textiles and Warner’s description noted that the bag was leather, including two Catlow twined baskets, two large “located about eight feet in from the mouth of the cave folded linear nets, snares, a leather bag, a badger head and two feet below the surface.” It was covered by a pouch, other hide and cordage, as well as a decorated piece of tule matting, and lay on a bed of grass, with a basalt maul. One of the nets returned an Accelerator Mass sage rope looped around the bag. The bag contained Spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon date of 340 ± 40 B.P. two large Catlow twined baskets, a leather bag, and The cache has been noted in previous publications, but leather-wrapped cordage and sinew bundles. -

In Search of the First Americas

In Search of the First Americas Michael R. Waters Departments of Anthropology and Geography Center for the Study of the First Americans Texas A&M University Who were the first Americans? When did they arrive in the New World? Where did they come from? How did they travel to the Americas & settle the continent? A Brief History of Paleoamerican Archaeology Prior to 1927 People arrived late to the Americas ca. 6000 B.P. 1927 Folsom Site Discovery, New Mexico Geological Estimate in 1927 10,000 to 20,000 B.P. Today--12,000 cal yr B.P. Folsom Point Blackwater Draw (Clovis), New Mexico 1934 Clovis Discovery Folsom (Bison) Clovis (Mammoth) Ernst Antevs Geological estimate 13,000 to 14,000 B.P. Today 13,000 cal yr B.P. 1935-1990 Search continued for sites older than Clovis. Most sites did not stand up to scientific scrutiny. Calico Hills More Clovis sites were found across North America The Clovis First Model became entrenched. Pedra Furada Tule Springs Clovis First Model Clovis were the first people to enter the Americas -Originated from Northeast Asia -Entered the Americas by crossing the Bering Land Bridge and passing through the Ice Free Corridor around 13,600 cal yr B.P. (11,500 14C yr B.P.) -Clovis technology originated south of the Ice Sheets -Distinctive tools that are widespread -Within 800 years reached the southern tip of South America -Big game hunters that killed off the Megafauna Does this model still work? What is Clovis? • Culture • Era • Complex Clovis is an assemblage of distinctive tools that were made in a very prescribed way. -

New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes

Shillito L-M, Blong J, Jenkins D, Stafford TW, Whelton H, McDonough K, Bull I. New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes. PaleoAmerica 2018 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited DOI link to article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 Date deposited: 23/10/2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk PaleoAmerica A journal of early human migration and dispersal ISSN: 2055-5563 (Print) 2055-5571 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ypal20 New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes Lisa-Marie Shillito, John C. Blong, Dennis L. Jenkins, Thomas W. Stafford Jr, Helen Whelton, Katelyn McDonough & Ian D. Bull To cite this article: Lisa-Marie Shillito, John C. Blong, Dennis L. Jenkins, Thomas W. Stafford Jr, Helen Whelton, Katelyn McDonough & Ian D. Bull (2018): New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes, PaleoAmerica, DOI: 10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 © 2018 The Author(s).