Tribal Textiles of Odisha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Entire Book

Orissa Review * April-May - 2009 Integration of Princely States Under Dr. Harekrushna Mahtab Balabhadra Ghadai The Constitution of Orissa Order-1936 got the different parts of the Princely States in Orissa. In approval of the British king on 3rd March, 1936. 1938 Praja Mandals (People's Association) were It was announced that the new province would formed and under their banner, struggle began come into being on 1st April, 1936 with Sir John for securing democratic rights. In the Princely State Austin Hubback, I.C.S. as the Governor. On the of Talcher a movement against feudal exploitation appointed day in a solemn ceremony held at the made significant advance. There was unrest at Ravenshaw College Hall, Cuttack, Sir John Austin Dhenkanal also where the Ruler tried his best to Hubback was administered the oath of office by suppress it. In October 1938, six persons including Sir Courtney Terrel, the Chief Justice of Bihar a 12 year old boy named Baji Rout died as a and Orissa High Court. The Governor read out result of firing. In Ranpur there was an out-break the message of goodwill received from the king- of lawlessness and the situation became serious emperor George VI and the Viceroy of India in January 1939 when the Political Agent Major Lord Linlithgow, for the people of Orissa. Thus, R.L. Bazelgatte was messacred by the mob on 5 the long cherished dream of the Oriya speaking January, 1939 at Ranpur. The troops were sent people of years at last became a reality. to crush the people's movement. -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

Tribes in India 208 Reading

Department of Social Work Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Regional Campus Manipur Name of The Paper: Tribal Development (218) Semester: IV Course Faculty: Ajeet Kumar Pankaj Disclaimer There is no claim of the originality of the material and it given only for students to study. This is mare compilation from various books, articles, and magazine for the students. A Substantial portion of reading is from compiled reading of Algappa University and IGNOU. UNIT I Tribes: Definition Concept of Tribes Tribes of India: Definition Characteristics of the tribal community Historical Background of Tribes- Socio- economic Condition of Tribes in Pre and Post Colonial Period Culture and Language of Major Tribes PVTGs Geographical Distribution of Tribes MoTA Constitutional Safeguards UNIT II Understanding Tribal Culture in India-Melas, Festivals, and Yatras Ghotul Samakka Sarakka Festival North East Tribal Festival Food habits, Religion, and Lifestyle Tribal Culture and Economy UNIT III Contemporary Issues of Tribes-Health, Education, Livelihood, Migration, Displacement, Divorce, Domestic Violence and Dowry UNIT IV Tribal Movement and Tribal Leaders, Land Reform Movement, The Santhal Insurrection, The Munda Rebellion, The Bodo Movement, Jharkhand Movement, Introduction and Origine of other Major Tribal Movement of India and its Impact, Tribal Human Rights UNIT V Policies and Programmes: Government Interventions for Tribal Development Role of Tribes in Economic Growth Importance of Education Role of Social Work Definition Of Tribe A series of definition have been offered by the earlier Anthropologists like Morgan, Tylor, Perry, Rivers, and Lowie to cover a social group known as tribe. These definitions are, by no means complete and these professional Anthropologists have not been able to develop a set of precise indices to classify groups as ―tribalǁ or ―non tribalǁ. -

Glossary on Scheduled Tribes Of

CENSUS OF INDIA~ 1961 MADHYA PRADESH GLOSSARY ON SCHEDULED TRIBES OF MADHYA PRADESH Hy K. C. DUBEY, Deputy Superintendent, Census Operations, Madhya Pradesh. 1969 In ,the '1961 Census it was origina11y proposed to prepare ethnographic notes on all the principal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes of Madhya Pradesh. Some work had been done in this direction and notes on some tribes were also prepared. However, for various reasons the project on ethnographic notes could not be completed. We in the State Census Office thought that whether or not the ethnographic notes are prepared, compilation of a glossary on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes would be" very useful to all concerned. It 'will' show the population for all Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and synonymous groups li'sted in the Sche.duled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Li.sts (Modification) Order, 1956 which information is not available in the Census publications and it will help to briefly introduce all such Scheduled Caste s, Scpeduled Tribe s and synonymous groups. 'l'he glossary, it was thought, would be more welcome to general administration thrul the detailed ethnographic note s. Thus, the preparation of glossary on Scheduled Tribes was taken in hand in 1963 ~~d it was eompleted in 1964. Because of various other·pre-occupations a similar glossary on Scheduled Castes could not be prepared. 'The g1.ossar~' prepared at the State Census Office was submitted to the Social Studies Section of the ~1Jin- cl . Registrar General. It was scrutinised there and the suggestions received from the Registrar General were incorporated in the glossary. -

Current Affairs Questions 30Th June 2020

Current Affairs Questions 30th June 2020 3 Exam Going to Covered in One Year In Just 450 Rs per month CG CHSL L PHAS JE E 8 STEN PRE/MAINS GD O ALL SUBJECTS MTS Question of the day Bahuda Yatra is conducted in the बहुदा यात्रा _______ राज्य में आयोजित state of _______. की जाती है। A. Gujarat A. गुजरात B. Maharashtra B. महाराष्ट्र C. Odisha C. ओडिशा D. Telangana D. तेलंगाना ● For smooth conduct of the Bahuda Yatra of Lord Jagannath and his siblings without participation of devotees, the Odisha government has decided to impose curfew in the Puri district in June. The Bahuda Yatra (return chariot festival) of the deities will be held on July 1. ● Lord Jagannath and his siblings will return from Gundicha Temple on three wooden chariots during the Yatra. ● भक्तों की भागीदारी के बिना भगवान जगन्नाथ और उनके भाई-बहनों की बहुदा यात्रा के सुचारु संचालन के लिए, ओडिशा सरकार ने जून में पुरी जिले में कर्फ्यू लगाने का फैसला किया है। देवताओं की बहुदा यात्रा (वापसी रथ उत्सव) 1 जुलाई को आयोजित की जाएगी। ● भगवान जगन्नाथ और उनके भाई यात्रा के दौरान तीन लकड़ी के रथों पर गुंडिचा मंदिर से लौटेंगे। Odisha • State: 1 April 1936 (Utkala Dibasa) • Capital: Bhubaneswar • Number of District : 30 • Governor: Ganeshi Lal • Chief Minister: Naveen Patnaik • Members of the Legislative Assembly: 147 • Lok Sabha Seats : 21 • Rajya Sabha Seats : 10 7 Festivals of Odisha ● Durga Puja ● Prathamastami ● Ratha Yatra ● Raja Parba ● Bali Jatra/Kartika Purnima ● Nuakhai ● Sitalsasthi ● Dhanu Jatra Odisha in Recent News ● On Raja Praba, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has greeted the people Of Odisha. -

Madhya Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2000 ______Arrangement of Sections ______Part I Preliminary Sections 1

THE MADHYA PRADESH REORGANISATION ACT, 2000 _____________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS _____________ PART I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title. 2. Definitions. PART II REORGANISATION OF THE STATE OF MADHYA PRADESH 3. Formation of Chhattisgarh State. 4. State of Madhya Pradesh and territorial divisions thereof. 5. Amendment of the First Schedule to the Constitution. 6. Saving powers of the State Government. PART III REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURES The Council of States 7. Amendment of the Fourth Schedule to the Constitution. 8. Allocation of sitting members. The House of the People 9. Representation in the House of the People. 10. Delimitation of Parliamentary and Assembly constituencies. 11. Provision as to sitting members. The Legislative Assembly 12. Provisions as to Legislative Assemblies. 13. Allocation of sitting members. 14. Duration of Legislative Assemblies. 15. Speakers and Deputy Speakers. 16. Rules of procedure. Delimitation of constituencies 17. Delimitation of constituencies. 18. Power of the Election Commission to maintain Delimitation Orders up-to-date. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes 19. Amendment of the Scheduled Castes Order. 20. Amendment of the Scheduled Tribes Order. PART IV HIGH COURT 21. High Court of Chhattisgarh. 22. Judges of Chhattisgarh High Court. 23. Jurisdiction of Chhattisgarh High Court. 24. Special provision relating to Bar Council and advocates. 25. Practice and procedure in Chhattisgarh High Court. 26. Custody of seal of Chhattisgarh High Court. 27. Form of writs and other processes. 28. Powers of Judges. 1 SECTIONS 29. Procedure as to appeals to Supreme Court. 30. Transfer of proceedings from Madhya Pradesh High Court to Chhattisgarh High Court. 31. Right to appear or to act in proceedings transferred to Chhattisgarh High Court. -

Development of Eco-Tourism in Tribal Regions of Orissa: Potential and Recommendations

Bond University Research Repository Development of eco-tourism in tribal regions of Orissa: Potential and recommendations Panigrahi, Nilakantha Licence: Unspecified Link to output in Bond University research repository. Recommended citation(APA): Panigrahi, N. (2005). Development of eco-tourism in tribal regions of Orissa: Potential and recommendations. (Research paper series : Centre for East-West Cultural & Economic Studies; No. 11). Bond University. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. For more information, or if you believe that this document breaches copyright, please contact the Bond University research repository coordinator. Download date: 01 Oct 2021 Bond University ePublications@bond Centre for East-West Cultural and Economic CEWCES Research Papers Studies 2-1-2005 Development of eco-tourism in tribal regions of Orissa: Potential and recommendations Nilakantha Panigrahi NKC Center for Development Studies, Orissa, India Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.bond.edu.au/cewces_papers Part of the Growth and Development Commons Recommended Citation Panigrahi, Nilakantha, "Development of eco-tourism in tribal regions of Orissa: Potential and recommendations" (2005). CEWCES Research Papers. Paper 9. http://epublications.bond.edu.au/cewces_papers/9 This Research Report is brought to you by the Centre for East-West Cultural and Economic Studies at ePublications@bond. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEWCES Research Papers by an authorized administrator of ePublications@bond. For more information, please contact Bond University's Repository Coordinator. -

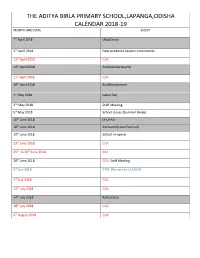

The Aditya Birla Primary School,Lapanga,Odisha Calendar 2018-19 Month and Date Event

THE ADITYA BIRLA PRIMARY SCHOOL,LAPANGA,ODISHA CALENDAR 2018-19 MONTH AND DATE EVENT 1st April 2018 UtkalDiwas 2nd April 2018 New Academic Session Commences 13th April 2018 CCA 14th April 2018 AmbedarkarJayanti 21st April 2018 CCA 30th April 2018 Buddha purnima 1st May 2018 Labor Day 2nd May 2018 Staff Meeting 5th May 2018 School closes (Summer break) 16th June 2018 Id-Ul-Fitr 18th June 2018 Sitalsasthi(Local Festival) 19th June 2018 School re-opens 23rd June 2018 CCA 25th to 29th June 2018 PA I 30th June 2018 CCA, Staff Meeting 6th July 2018 PTM (Nursery to CLASS-II) 7th July 2018 CCA 13th July 2018 CCA 14th July 2018 RathaYatra 28th July 2018 CCA 4th August 2018 CCA 15th August 2018 Independence Day Celebration 18th August 2018 CCA 22nd August 2018 BakriEid/ Id-ul-Zuha 24th August 2018 CCA 25th August 2018 Staff Meeting 26th August 2018 RakshaBandhan 1st September 2018 CCA 2nd September 2018 Janmastami Celebration 5th September 2018 Teacher’s Day Celebration 9th September 2018 CCA 13th September 2018 Ganesh Chaturthi 14th and 15th September 2018 Nuakhai (Local Festival) 21st September 2018 Muharram 22nd September 2018 CCA 24th to 29th September 2018 Half yearly 28th September 2018 CCA 29th September 2018 Staff Meeting 2nd October 2018 Mahamta Gandhi Jayanti 6th October 2018 CCA 8th October 2018 Mahalaya 12th October 2018 CCA 13th October 2018 PTM (LKG to CLASS II) 16thto 20th October 2018 Autumn Break 18th October 2018 Dussehra 22nd October 2018 School Reopens 24th October 2018 Kumarpurnima 26th October 2018 CCA 27th October 2018 CCA -

Indian Tribal Ornaments; a Hidden Treasure

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 10, Issue 3 Ver. II (Mar. 2016), PP 01-16 www.iosrjournals.org Indian Tribal Ornaments; a Hidden Treasure Dr. Jyoti Dwivedi Department of Environmental Biology A.P.S. University Rewa (M.P.) 486001India Abstract: In early India, people handcrafted jewellery out of natural materials found in abundance all over the country. Seeds, feathers, leaves, berries, fruits, flowers, animal bones, claws and teeth; everything from nature was affectionately gathered and artistically transformed into fine body jewellery. Even today such jewellery is used by the different tribal societies in India. It appears that both men and women of that time wore jewellery made of gold, silver, copper, ivory and precious and semi-precious stones.Jewelry made by India's tribes is attractive in its rustic and earthy way. Using materials available in the local area, it is crafted with the help of primitive tools. The appeal of tribal jewelry lies in its chunky, unrefined appearance. Tribal Jewelry is made by indigenous tribal artisans using local materials to create objects of adornment that contain significant cultural meaning for the wearer. Keywords: Tribal ornaments, Tribal culture, Tribal population , Adornment, Amulets, Practical and Functional uses. I. Introduction Tribal Jewelry is primarily intended to be worn as a form of beautiful adornment also acknowledged as a repository for wealth since antiquity. The tribal people are a heritage to the Indian land. Each tribe has kept its unique style of jewelry intact even now. The original format of jewelry design has been preserved by ethnic tribal. -

Final Report Evaluation Study of Tribal/Folk Arts and Culture in West Bengal, Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhatisgrah and Bihar

Final Report Evaluation Study of Tribal/Folk Arts and Culture in West Bengal, Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhatisgrah and Bihar Submitted to SER Division Planning Commission Govt. of India New Delhi Submitted by Gramin Vikas Seva Sanshtha Dist. 24 Parganas (North), West Bengal 700129 INDIA Executive Summary: India is marked by its rich traditional heritage of Tribal/Folk Arts and Culture. Since the days of remote past, the diversified art & cultural forms generated by the tribal and rural people of India, have continued to evince their creative magnificence. Apart from their outstanding brilliance from the perspective of aesthetics , the tribal/folk art and culture forms have played an instrumental role in reinforcing national integrity, crystallizing social solidarity, fortifying communal harmony, intensifying value-system and promoting the elements of humanism among the people of the country. However with the passage of time and advent of globalization, we have witnessed the emergence of a synthetic homogeneous macro-culture. Under the influence of such a voracious all-pervasive macro-culture the diversified heterogeneous tribal/folk culture of our country are suffering from attrition and erosion. Thus the stupendous socio-cultural exclusivity of the multifarious communities at the different nooks and corners of our country are getting endangered. Under such circumstances, the study–group Gramin Vikash Seva Sanstha formulated a project proposal on “Evaluation Study of Tribal/Folk Arts and Culture in West Bengal, Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhatisgrah -

World Bank Document

IPP255 v3 SOCIAL ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized ORISSA COMMUNITY TANK MANAGEMENT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by Verve Consulting for Orissa Community Tank Development & Management Society, Department of Water Resources, Government of Orissa Dated the 7th of December 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized Orissa Community Tank Management Project Social Assessment Contents Sl. No. Subject Page 1. Introduction 4 2. Social Assessment Study 4 3. Study methodology 5 4. Tank irrigation systems in Orissa: the challenges 7 and opportunities 5. Diversity in tank irrigation systems in Orissa 10 6. Stakeholder Analysis 14 7. Perceived Impact on beneficiaries 26 8. Issues of significance for the project 27 9. Design elements to approach the issues 29 10. Orissa tank rehabilitation: Process Map / Cycle 36 11. Major risks and assumptions in the project 39 Annexure Brief summary note on the review of Orissa Pani Panchayat Act, 2002 and assessment of the institutional capacity of Pani Panchayats _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Verve Consulting 2 Orissa Community Tank Management Project Social Assessment _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Verve Consulting 3 Orissa Community Tank Management Project Social Assessment Abbreviations ADM Additional District Magistrate AMS Agriculture Marketing System ANM Auxiliary Nurse Mid-wife AVAS Assistant Veterinary Assistant Surgeon AWW Angan Wadi Worker -

Sonabera Ocr

T Gatibera amdist. a Up in the hill ran.iesl o!etting there lives ~n picture!quc phy11ca Sonabera plateau. in the plateau called h jias a small rribc 1 Kalahandi distrjct F / ~ lrn~ing racial and of about 7000 popu a 1J° Gonds of Orissa• cultural affinity w1tl'i,! l~ and lack of The g~gr~phical rr~e::vournble to the communication have bee . g the distinctive ibal pie for preservm 'be tri peo k f this little known trrt . cultural landmar s O · •• In such a state of isolation the BhunJtaJ have had continued a healthy,. vigorous a~ colourful ltfe devoid of a?!. m~1scnm1na. e contact with the outsid~ c1Vt!1zat1on. But in the recent times this isolation has bro en down and there has been inflow and outflow of population to and from the plateau. As .a result of such cultural contacts th~ tradi• tional tribal life is being considerably disrupted and in the process of transfor• mation. In a large measure the contact has been a serious threat to the community and in order to keep themselves off from the debasing effects of cultural contact the Bhunjias, particularly the women section of the community who are the guardian of their tribal tradition have evolved suitable measures to safeguard their identity and integrity. / This book which is written on the basis of ) direct observation and first hand contact with the people through intensive anthro• pological field investigation presents the traditional social system and cultural pattern of the tribe, types of changes which are taking place in the area and nature of problems and anxieties which have surfaced in the wake of increased external contact and communication.