In Conversation with Nick Gold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

" African Blues": the Sound and History of a Transatlantic Discourse

“African Blues”: The Sound and History of a Transatlantic Discourse A thesis submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Saul Meyerson-Knox BA, Guilford College, 2007 Committee Chair: Stefan Fiol, PhD Abstract This thesis explores the musical style known as “African Blues” in terms of its historical and social implications. Contemporary West African music sold as “African Blues” has become commercially successful in the West in part because of popular notions of the connection between American blues and African music. Significant scholarship has attempted to cite the “home of the blues” in Africa and prove the retention of African music traits in the blues; however much of this is based on problematic assumptions and preconceived notions of “the blues.” Since the earliest studies, “the blues” has been grounded in discourse of racial difference, authenticity, and origin-seeking, which have characterized the blues narrative and the conceptualization of the music. This study shows how the bi-directional movement of music has been used by scholars, record companies, and performing artist for different reasons without full consideration of its historical implications. i Copyright © 2013 by Saul Meyerson-Knox All rights reserved. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my utmost gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Stefan Fiol for his support, inspiration, and enthusiasm. Dr. Fiol introduced me to the field of ethnomusicology, and his courses and performance labs have changed the way I think about music. -

NEW RELEASE GUIDE March 19 March 26 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 12 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 19

ada–music.com @ada_music NEW RELEASE GUIDE March 19 March 26 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 12 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 19 2021 ISSUE 7 March 19 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 12 NEW EP ELASTICITY FROM SERJ TANKIAN TRACKLISTING 1. ELASTICITY 2. YOUR MOM 3. HOW MANY TIMES? 4. RUMI 5.ELECTRIC YEREVAN • New EP “ELASTICITY” from Serj Tankian (System Of A Down) out on 3/19/21. UPC: 4050538653694 Returnable: Yes CAT: 538653692 Explicit: Yes • First Instant Grat track “ELASTICITY” out Box Lot: 30 CD File Under: Rock SRP: $9.98 on 2/5/21 together with a video and EP Packaging: Digipack Release Date: 3/19/21 4 050538 653694 pre-order. • “ELECTRIC YEREVAN” will be the focus track and comes out alongside the EP on 3/19/21. It’s will also be featured in a trailer and end credits for the upcoming Serj Tankian directed documentary TRUTH IS POWER out on 4/27/21. Artist: Saxon Release date: 19th March 2021 Title: Inspirations Territory: World Ex. Japan Genre: Metal FORMAT 1: CD Album (Digipack) Cat no: SLM106P01 / UPC: 190296800504 SPR: $13.99 - 3% Discount applicable till Street Date FORMAT 2: Vinyl Album Cat no: SLM106P42 / UPC: 190296800481 SPR: $34.98 SAXON PROUDLY DISPLAY THEIR “INSPIRATIONS” WITH NEW CLASSIC COVERS RELEASE British Heavy Metal legends Saxon will deliver a full-roar-fun-down set of covers on March 19th 2021 (Silver Lining Music), with their latest album Inspirations, which drops a brand new 11 track release featuring some of the superb classic rock songs that influenced Biff Byford & the band. From the crunching take on The Rolling Stones’ ‘Paint It Black’ and the super-charged melodic romp of The Beatles’ ‘Paperback Writer’ to their freeway mad take on Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Stone Free’, Saxon show their love and appreciation with a series of faithful, raw and ready tributes. -

Sonic Records: Listening to Afro-Atlantic Literature and Music, 1650-1860

Sonic Records: Listening to Afro-Atlantic Literature and Music, 1650-1860 by Mary Caton Lingold Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor ___________________________ Laurent Dubois ___________________________ Tsitsi Jaji ___________________________ Louise Meintjes Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 ABSTRACT Sonic Records: Listening to Afro-Atlantic Literature and Music, 1650-1860 by Mary Caton Lingold Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor ___________________________ Laurent Dubois ___________________________ Tsitsi Jaji ___________________________ Louise Meintjes An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Mary Caton Lingold 2017 Abstract “Sonic Records” explores representations of early African diasporic musical life in literature. Rooted in an effort to recover the early history of an influential arts movement, the project also examines literature and sound as interdependent cultural spheres. Increasingly, the disciplines of literature and history have turned their attention to the Atlantic world, charting the experience of Africans living in the -

ALBUM Title ) 01

2006/1/28 ( ALBUM title ) 01. Flesh and Blood / Solomon Burke Don't Give Up On Me 02. Richard Pryor Addresses A Tearful Nation / Joe Henry Scar 03. Stop / Joe Henry Scar 04. Guilty By Association / Joe Henry & Madonna Sweet Relief II: Gravity Of The Situation 05. Homecoming / Joe Henry Real - The Tom T.Hall Project 06. Safe With Me / Joe Henry Music From The Motion Picture Feeling Minnesota 07. Loves You Madly / Joe Henry Tiny Voices 08. If Jesus Drove A Motor Home / Jim White Drill A Hole In That Substrate And Tell Me What You See 09. Little Bombs / Aimee Mann The Forgotten Arm 10. Studying Stones / Ani DiFranco Knuckle Down 11. Soul Of A Man / Susan Tedeschi Hope And Desire 12. Joy / Bettye LaVette I've Got My Own Hell To Raise 13. When The Candle Burns Low / Ann Peebles I Believe To My Soul 14. Keep On Pushing / Mavis Staples I Believe To My Soul 15. Both Ways / Billy Preston I Believe To My Soul 16. Yes We Can Can / Allen Toussaint Our New Orleans 17. Backwater Blues / Irma Thomas Our New Orleans 18. Hackensack / Thelonious Monk Criss-Cross 2006/1/21 ( ALBUM title ) 01. Get Rhythm / Joaquin Phoenix Walk The Line Original Motion Picture Soundtrack 02. Goodness Gracious Me / Peter Sellers & Sophia Loren Peter And Sophia 03. That's The Way God Planned It / Billy Preston That's The Way God Planned It 04. How Can You Mend A Broken Heart / Al Green Let's Stay Together 05. Drive She Said / Stan Ridgway Fly On The Wall : Music And Commentary From Stan Ridgway 06. -

Nick Gold, the Musical Matchmaker Who Gave Mali the Blues •

Nick Gold, the Musical Matchmaker Who Gave Mali the Blues • Ali Farka Touré, left, with Nick Gold, who recorded him for World Circuit Records in sessions in Bamako, Mali, in 2004. Two of the resulting albums are due out this week. Mr. Touré died in March. Credit... By Ben Sisario • July 23, 2006 FOR the final recording sessions of Ali Farka Touré, the sage Malian guitarist who died in March, Nick Gold chose a particularly memorable location. Mr. Gold, the proprietor of World Circuit Records, Mr. Touré’s label, needed a very large space, and Mr. Touré, who was suffering from cancer, wanted to remain in Mali. So a temporary studio was set up on the top floor of the thatched-roof Hôtel Mandé in Bamako, the capital, where the wide windows offered panoramas of life along the Niger River. “All you can see is river and grasslands and villages and people in pirogues and canoes and boats,” Mr. Gold said in a recent interview. “It’s just beautiful.” Over a few fruitful weeks in June and July 2004 Mr. Gold produced three albums. The first, “In the Heart of the Moon,” by Mr. Touré and the kora (harp) player Toumani Diabaté, was released last year and won a Grammy Award for best traditional world-music album. The other two will be released on Tuesday: “Boulevard de l’Indépendance” by Mr. Diabaté’s 30-odd-piece Symmetric Orchestra — hence the need for the big room — and Mr. Touré’s “Savane,” a series of steady, pulsating meditations on the virtues of farming and hard work, in music that bridges modal West African traditions with the blues. -

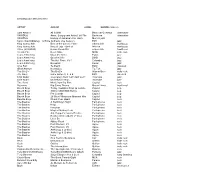

Cd Collection For

CD COLLECTION JAN 2013 ARTIST ALBUM LABEL GENRE (approx) Sam Amidon All Is Well Bedroom Commun. alternative VARIOUS Amer. Song-poem Anthol. 60-70s Bar/none alternative VARIOUS History of Jamaican Voc Harm. Munich jazz Cannonball Adderley & Ernie Andrews Live Session EMI jazz King Sunny Ade Best of the Classic Years Shanachie world pop King Sunny Ade King of Juju - Best of Wrasse world pop Africa (VARIOUS) Never Stand Still Ellipsis Arts traditional Arcade Fire Neon Bible MRG indie rock Louis Armstrong Mack the Knife Pablo jazz Louis Armstrong Greatest Hits BMG jazz Louis Armstrong The Hot Fives, Vol 1 Columbia jazz Louis Armstrong Essential Cedar jazz Arvo Part Te Deum ECM classical Gilad Atzmon Nostalgico Tip Toe jazz The B-52's The B-52's Warner Bros indie rock J.S. Bach Cello Suites 2, 3, & 6 EMI classical Chet Baker sings/plays from "Let's Get Lost" Riverside jazz Chet Baker Chet Baker Sings Riverside jazz The Band Music from Big Pink Capitol rock Bajourou Big String Theory Green Linnet traditional Beach Boys Today / Summer Days (& Summ.. Capitol pop Beach Boys Smiley Smile/Wild Honey Capitol pop Beach Boys Pet Sounds Capitol pop Beach Boys 20 Good Vibrations-Greatest Hits Capitol pop Beastie Boys Check Your Head Capitol rock The Beatles A Hard Day's Night Parlophone rock The Beatles Help! Parlophone rock The Beatles Revolver Parlophone rock The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour Parlophone rock The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts… Parlophone rock The Beatles Beatles (white album) (2-disc) Parlophone rock The Beatles Let It Be Parlophone -

Rg to Mali Booklet

MUSIC ROUGH GUIDES THE ROUGH GUIDE to the music of Mali To my mind, Mali is the crown jewel of West Africa to flat rooftops. The glassy waters of the River proud. Furthermore, it was clear that home- the founding of the Mande empire. As … though I only really ended up there by chance, Niger were perfectly still, interrupted only by the grown music took pride of place – voices such as commentators, advisers to their patrons and safe- and the luck of being in the right place at the right silhouette of black pirogues waiting to be loaded Boubacar Traore, Kandia Kouyate, Djeneba Seck keepers of an ancient tradition, jelis perform an time. With a few weeks off from university in Togo, for their journey upstream. Dry, arid and and Ali Farka Toure were some of the first I heard extremely important role in society and their and heading away from the coastal belt, I made landlocked though it is, the landscape is from local record players. profession is closely guarded. The class is my way through the forested plateau region, up formidable.’ endogamous and surnames are caste-based, so to the north of the country, and over the border Of course, I later discovered that Malian music certain names are held predominantly by to Burkino Faso, cloaked in a haze from the But without a doubt, for me the greatest discovery has a vast international following and is a force jelis, including Kouyate, Kante, Diabate, Tounkara Harmattan dust. Outside a bus station in Bobo – with little previous knowledge at the time – was to be reckoned with in the world music scene. -

L'echiquier Mp3 Collection by Genre/Artist/Album 12/09/2009

L'Echiquier mp3 collection by Genre/Artist/Album 12/09/2009 13:16 Genre Artist Album Africa - Fusion Dee Dee Bridgewater Red Earth - A Malian Journey African Ali Farka Touré Ali Farka Toure Green Red River, The Source, The Ali Farka Touré and Toumani Diabeté In the Heart of The Moon African - Electronic Vieux Farka Touré Remixed: Ufos Over Bamako Arabo-Andalouse Christian Poche La musique Asian - New Age Asian Journal Various Artists - Asian Journal ( Blues Leon Redbone Sugar Blues - Rock Rory Gallagher Blueprint Blues - Soul Hip Replacments (The) Blues and Soul Stripped to The Bone Carols 20 Classic Christmas Carols 20 Classic Christmas Carols Various Artists 20 Christmas Carols Classical BBC National Orchestra of Wales Walton, William BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Schubert No 9 (Great) Bedrich Smetana Les Grands Romantiques Brazilian Guitar Quartet, The Essencia Do Brasil Cheryl Studer, John Browning Barber: The Complete Songs [Disc 1] Choeur Et Orchestre Symphonique De Grieg Chopin - Tamas Vasary Chopin - Ballades and Liszt Annees De Ciccolini, Aldo Satie Piano Works (1 of 2) Satie Piano Works (2 of 2) Daniel Barenboom Daniel Barenboom Debussy, Satie, Ravel Arabesque Edith Vogel Beethoven: Piano Sonatas, Op. 106 & Edvard Grieg Les Grands Romantiques Ensemble Millenarium Llibre Vermell De l'Abbaye De Montserrat Françoise Hardy Tant De Belles Choses Girolamo Frescobaldi Frescobaldi Arie Musicali (1 of 2) Monteverdi Quinto Libro De' Madrigali - Alessandrini Ochestre sympohique de Montréal - Holst - The Planets Page 1 sur 17 Genre Artist Album Pergolesi: Rene Jacobs Pergolesi Stabat Mater Satie, Erik: Bruno Laplante Et Marc Durand Intégrales Des Mélodies Et Des Sibelius (Karajan) Sibelius Symphony No. -

El Oído Pensante- Año 1

Article / Artículo / Artigo I Play Wassoulou, Jeli, Songhay and Tuareg Music: Adama Drame in Postcolonial Mali, Bimusical or Multimusical? Luis Gimenez Amoros Rhodes University, South Africa [email protected] Abstract Adama is an accomplished guitarist in diverse Malian styles. The Malian guitarist is able to analyse the forms and contexts of the national musical styles he performs in regards to: the musical interaction with other musicians, timbre, rhythm and melody. In this article, I examine how Adama performs a wide range of Malian musical styles in Bamako; and how he represents and participates in different postcolonial musical cultures in Mali. In this article, Adama’s capability of understanding different national musical styles as part of the social contexts in a variety of musical cultures in Mali is defined as multimusical. Multimusicality debates the concept of bimusicality (Hood 1960) defined as the capacity of performing both, a western and non-western musical style; therefore separating musically the Self [western music] and the Other [non-western]. For Adama, the concept of multimusicality does not only extend the possibility of learning more than two musical styles, but examines the national styles he is able to play as a Malian citizen (insider) and not as the Other. This paper is based on my musical contact with Adama Drame during November-December 2006 in Mali and in the last eight years. Keywords: Multimusicality, bimusicality, musical cosmopolitanism, Malian music, postcolonial Mali Toco música wassoulou, jeli, songhay y tuareg: Adama Drame en Mali postcolonial, ¿bimusicalidad o multimusicalidad? Resumen Adama es un guitarrista competente en diversos estilos musicales de Malí. -

AFRICAN MUSIC and PEACE Conrad Grebel University College/UW 10:00 – 11:20, Monday and Wednesday, Room 1300, Professor Carol Ann Weaver

MUSIC 390/PACS 301, WINTER 2013 – AFRICAN MUSIC AND PEACE Conrad Grebel University College/UW 10:00 – 11:20, Monday and Wednesday, Room 1300, Professor Carol Ann Weaver Week Dates Material Studied; Assignment Listings 1 Jan. 7 Overview of continental Africa – its music and peace/conflict issues Jan. 9 Guest, PACS Prof. Reina Neufeldt, “Snapshots of Peace-building in Africa” Readings: G&G: Chapters 1, 2 – Intro and Geography 2 Jan. 14, 16 Senegal and Guinea – national issues, perspectives, music Readings: G&G: Chapter 3 – History 3 Jan. 21 Nigeria – national issues, perspectives, music Nigerian Documentary DVD, The Amam and the Pastor – in-class screening Jan. 23 Guest Lecturers, Dave and Mary Lou Klassen, “Peace Work in Nigeria” Readings: G&G: Chapter 4 – Politics 4 Jan. 28, 30 Mali and Cameroon – national issues, perspectives, music Readings: G&G: Chapter 5 – Economics Short-short essay on Nigeria DVD, G&G questions (Ch. 1-5), due Wed., Jan. 30 5 Feb. 4 Congo (DRC) – national issues, perspectives, music Guest: Marlene Epp (Grebel History/PACS), “Dancing with Congolese Women” Feb. 6 Guest: Maurice Mondengo (Congolese Musician), “Having to Leave The Congo” Readings: G&G: Chapter 6 – International Relations 6 Feb. 11 Uganda – national issues & perspectives Guest Lecturer, Jennifer Ball, “Children, War, and Peace in Uganda” Listening Quiz 1, Mon., Feb. 11: Files 1 – 6 (Senegal through Congo) Feb. 13* Ugandan DVD, War Dance *Screening at 9:00AM, Wed. Feb. 13, Rm 1300 Readings: G&G: Chapters 7 – Population, Urbanization, AIDS READING WEEK, -

Music 96676 Songs, 259:07:12:12 Total Time, 549.09 GB

Music 96676 songs, 259:07:12:12 total time, 549.09 GB Artist Album # Items Total Time A.R. Rahman slumdog millionaire 13 51:30 ABBA the best of ABBA 11 43:42 ABBA Gold 9 36:57 Abbey Lincoln, Stan Getz you gotta pay the band 10 58:27 Abd al Malik Gibraltar 15 54:19 Dante 13 50:54 Abecedarians Smiling Monarchs 2 11:59 Eureka 6 35:21 Resin 8 38:26 Abel Ferreira Conjunto Chorando Baixinho 12 31:00 Ace of Base The Sign 12 45:49 Achim Reichel Volxlieder 15 47:57 Acid House Kings Sing Along With 12 35:40 The Acorn glory hope mountain 12 48:22 Acoustic Alchemy Early Alchemy 14 45:42 arcanum 12 54:00 the very best of (Acoustic Alchemy) 16 1:16:10 Active Force active force 9 42:17 Ad Vielle Que Pourra Ad Vielle Que Pourra 13 52:14 Adam Clayton Mission Impossible 1 3:27 Adam Green Gemstones 15 31:46 Adele 19 12 43:40 Adele Sebastan Desert Fairy Princess 6 38:19 Adem Homesongs 10 44:54 Adult. Entertainment 4 18:32 the Adventures Theodore And Friends 16 1:09:12 The Sea Of Love 9 41:14 trading secrets with the moon 11 48:40 Lions And Tigers And Bears 13 55:45 Aerosmith Aerosmith's Greatest Hits 10 37:30 The African Brothers Band Me Poma 5 37:32 Afro Celt Sound System Sound Magic 3 13:00 Release 8 45:52 Further In Time 12 1:10:44 Afro Celt Sound System, Sinéad O'Connor Stigmata 1 4:14 After Life 'Cauchemar' 11 45:41 Afterglow Afterglow 11 25:58 Agincourt Fly Away 13 40:17 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir Saint Hubert 11 38:26 Ahmad El-Sherif Ben Ennas 9 37:02 Ahmed Abdul-Malik East Meets West 8 34:06 Aim Cold Water Music 12 50:03 Aimee Mann The Forgotten Arm 12 47:11 Air Moon Safari 10 43:47 Premiers Symptomes 7 33:51 Talkie Walkie 10 43:41 Air Bureau Fool My Heart 6 33:57 Air Supply Greatest Hits (Air Supply) 9 38:10 Airto Moreira Fingers 7 35:28 Airto Moreira, Flora Purim, Joe Farrell Three-Way Mirror 8 52:52 Akira Ifukube Godzilla 26 45:33 Akosh S. -

El Oído Pensante, Vol

Article / Artículo / Artigo I Play Wassoulou, Jeli, Songhay and Tuareg Music: Adama Drame in Postcolonial Mali, Bimusical or Multimusical? Luis Gimenez Amoros Rhodes University, South Africa [email protected] Abstract Adama is an accomplished guitarist in diverse Malian styles. The Malian guitarist is able to analyse the forms and contexts of the national musical styles he performs in regards to: the musical interaction with other musicians, timbre, rhythm and melody. In this article, I examine how Adama performs a wide range of Malian musical styles in Bamako; and how he represents and participates in different postcolonial musical cultures in Mali. In this article, Adama’s capability of understanding different national musical styles as part of the social contexts in a variety of musical cultures in Mali is defined as multimusical. Multimusicality debates the concept of bimusicality (Hood 1960) defined as the capacity of performing both, a western and non-western musical style; therefore separating musically the Self [western music] and the Other [non-western]. For Adama, the concept of multimusicality does not only extend the possibility of learning more than two musical styles, but examines the national styles he is able to play as a Malian citizen (insider) and not as the Other. This paper is based on my musical contact with Adama Drame during November-December 2006 in Mali and in the last eight years. Keywords: Multimusicality, bimusicality, musical cosmopolitanism, Malian music, postcolonial Mali Toco música wassoulou, jeli, songhay y tuareg: Adama Drame en Mali postcolonial, ¿bimusicalidad o multimusicalidad? Resumen Adama es un guitarrista competente en diversos estilos musicales de Malí.