Verbeeten Review Published

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

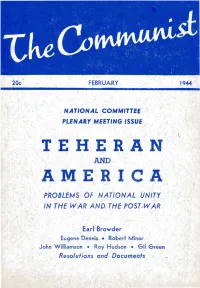

Earl Browder F I Eugene Dennis • Robert Minor John Willia-Mson • Roy · Hudson • Gil G R,Een Resolutions And.· Documents I • I R

I . - > 20c FEBRUARY 1944 ' .. NATIONAL COMMITTE~ I PLENARY MEETING ISSUE ,. - • I ' ' ' AND PROBLEMS OF NATIONAL UNIT~ ' ·- ' . IN THE WAR AND THE POST-~AR I' • Earl Browder f I Eugene Dennis • Robert Minor John Willia-mson • Roy · Hudson • Gil G r,een Resolutions and.· Documents I • I r / I ' '. ' \' I , ... I f" V. I. L~NIN: A POLITICAL, BIOGRAP,HY 1' ' 'Pre pared by' the Mc);;·Engels.Le nin 'Institute, t his vo l ' ume provides b new ana authoritative 'study of t he life • and activities of the {9under and leader of the Soviet . Union up to thf;l time of Le11i n's death. P r.~ce $ 1.90 ~· .. • , f T'f'E RED ARMY By .Prof. I. Mi111. , The history and orgon lfqtion of the ~ed Army ·.and a iJt\fO redord1of its ~<;hievem e nfs fr9 m its foundation fhe epic V1cfory ,tal Stalingrad. Pl'i ce $1.25 I SOVIET ECONOMY AND !HE WAR By Dobb ,. ' Maur fc~ • ---1· •' A fadyal record of economic developm~nts during the last .few years with sp6""cial re?erence ..to itheir bearing '/' / on th~ war potentiaJ··and· the needs of the w~r. Price ~.25 ,- ' . r . ~ / .}·1 ' SOVIET PLANNING A~ D LABOR IN PEACE AND WAR By Maurice Oobb ' ' 1 - I A sh~y of economic pl~nning, the fln~ncia l . system, ' ' ' . work , wages, the econorpic effects 6f the war, end other ' '~>pecial aspects of the So'liet economic system prior to .( and during the w ~ r , · Price ·$.35 - I ' '-' I I • .. TH E WAR OF NATIONAL Llij.E R ATIO~ (in two· parts) , By Joseph ·stalin '· A collecfion of the wa~fime addr~sses of the Soviet - ; Premier and M<~rshal of the ·Rep Army, covering two I years 'o.f -the war ~gains+ the 'Axis. -

Soviet Toilers Greet Moscow Regional Conference

Page Six DAILY WORKER, NEW YORK. FRIDAY. JANUARY 19, 1934 Daily Mr. Qreen On Fascism Chicago Workers to “You'se Guys Don’t Know When You Got It Soft” —By Burch Foreign Policy -IkTUI «UI 5.4. (StCTION Os COMMUNIST EDHEN WILLIAM GREEN, president Os the American COMMUNIST MNTT U INTI«N»nOMI> " j Federation of Labor, raises his hands in a gesture “America's Only Working Class Daily Newspaper'' Sees U. S. of horror against Hitler’s labor code, we cannot fail Greet Delegates on Body FOUNDED 1924 but to observe that this gentleman's own hands have ! EXCEPT BY THE ” PUBLISHED DAILY. SUNDAY. fascist stains on them. Way to RS.U. Meet 7; WarWithJapan COMPROD AILY PUBLISHING CO., TNC., 50 East 13th On the publication of the German Fascist labor Street, New York. N. Y". laws, decreeing formally the end of all trade unions j 30 from Middle We*t Tokyo Policy Telephone: ALgonquin 4-7954 and the absolute submission of the workers to the j Threatens Nazi conditions of wages and Mr Cable Address: "Daiv.orfc," New York, N. Y. conditions, Green j WillLeave Soon; Chicago U.S. Hegemony in China, V«-*shin*»n Bureau: Room 054, National Press Building. issued a strongly worded statement. 14th and p. St.. Washington, D. C. Send-Off Jan. 19 Pacific, It Reports He declared that Hitler’s labor signified ! Subscription Rates: code the “enslavement and autocratic control” for the German | NEW YORK.—A bus-load currying B; Mail: (except Manhattan Bronx', t rear, and *6.00: delegates Chicago organiza- WASHINGTON, Jan. -

Nemmy Sparks Papers

THE NEMMY SPARKS COLLECTION Papers, 1942-1973 (Predominantly 1955-1973) 5 linear feet Accession No. 617 The papers of Nemmy Sparks were placed in the Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs in September of 1973 by Mrs. Nemmy Sparks. Nemmy Sparks was born Nehemiah Kishor on March 6, 1899. In 1918 he graduated as a chemist from the College of the City of New York, went to sea for two and a half years and in 1922 went to Siberia on the Kuzbas project. Mr. Sparks joined the Communist Party in 1924 and worked in organizing the seamen on the waterfront in New York, as well as founding and edi- ting the Marine Workers Voice. In 1932 he headed the Communist Party in New England, later becoming head of the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania party, and on to succeed Gene Dennis in 1937 as head of the Wisconsin Communist Party. In 1945 he was elected chairman of the Southern California Communist Party. Mr. Sparks was assigned to national work in 1950, returning to California in 1957, as legislative director, and later becoming educational director. Nemmy Sparks died May 9, 1973. Mr. Sparks papers include his unpublished manuscripts; his autobiogra- phy Prelude and Epilog, Common Sense about Communism as well as The Nation and Revolution, which was published posthumously. His papers reflect the internal struggles of the Communist Party in the latter half of the 1950's as well as after the Czechoslovakian situation in 1968. Pseudonyms used by Mr. Sparks were Richard Loring, John Nemmy and Neil Stanley. Important subjects in this collection include: National Secretariat discussions, 1956-1957 Communist Party programs, resolutions, bulletins and reports Outlines of study of the history of the Communist Party Outlines of study of Marxism-Leninism The Nemmy Sparks Collection -2- Other subjects include: Cyber culture Racism Czechoslovakia Seventieth Birthday Celebration Economy Translation Iron Mountain Twenty-six (resignations of 1958) New Left Among the correspondents are: James S. -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk McIlroy, John and Campbell, Alan (2019) Towards a prosopography of the American communist elite: the foundation years, 1919–1923. American Communist History . ISSN 1474-3892 [Article] (Published online first) (doi:10.1080/14743892.2019.1664840) Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/28259/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

1 "Commitment and Crisis: Jews and American Communism" Tony Michels

"Commitment and Crisis: Jews and American Communism" Tony Michels (Univ. of Wisconsin, Madison) Introduction During the 1920s, Jews formed the American Communist Party’s most important base of support. The party’s Jewish Federation, its Yiddish-speaking section, claimed around 2,000 members or 10% of the party’s overall membership in mid-decade. Yet that figure hardly conveys the extent of Jewish involvement with Communism during the 1920s. To begin with, a significant number of Jews were members of the party’s English-, Russian-, Polish-, and Hungarian-speaking units. Moreover, Communism’s influence among Jews extended far beyond the narrow precincts of party membership. The Communist Yiddish daily, Di frayhayt, enjoyed a reputation for literary excellence and reached a readership of 20,000-30,000, a higher circulation than any Communist newspaper, including the English-language Daily Worker. Jewish Communists built a network of summer camps, schools for adults and children, cultural societies, theater groups, choirs, orchestras, and even a housing cooperative in the Bronx that encompassed tens of thousands of Communist Party members, sympathizers, and their families. Finally, Communists won a strong following among Jewish workers in the needle trades and even came close to capturing control of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union between 1923 and 1926. (A remarkable seventy percent of ILGWU members belonged to Communist-led locals during those years.) Viewed through the lens of immigrant Jewry, then, Communism's golden age was not the Great Depression but rather the preceding decade. To be sure, Jewish Communists were in the minority, but 1 they were far from isolated. -

POLITICAL AFFAIRS a to the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism

25* FEBRUARY 1948 New Tasks and realignments in the Struggle for the Jewish State by Alexander Bittelman ־"166 - .ץ MAX GORDON ־56:335,{=> B ACTIVITIES OF THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE, C.P.S.U. GEORGI M. MALENKOV ILLUSION AND REALITY By CHRISTOPHER CAUDWELL —a "study in the sources of poetry" with a philosophy of art in terms of both the individual and society. —begins with a study of the origins of art in tribal life; discusses the development of English poetry from Shakespeare to modern times; examines the language of poetry, the differences between art and science. Price: $3-75 AMERICAN TRADE UNIONISM By WILLIAM Z. FOSTER —selected writings by a veteran Communist Party and labor leader on the past 35 years of trade union activity. —selections include: the Great Steel Strike; Trade Union Educa- tional League; the Question of the Unorganized; Trade Union Unity League; Organization of Negro Workers; Industrial Union- ism; Communists and the Trade Unions; New World Federation of Labor; the Trade Unions and Socialism. Price: $2.85 HISTORY of the LAROR MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES By PHILIP S. FONER —a detailed study of the struggles of the working class to win an improved status in American society. —a history of the rise of trade unions and their influence on the development of American capitalism. —an authoritative work based on new and previously unpublished material. Price: $3.75 NEW CENTURY PUBLISHERS .New York 3, N. Y ״ Broadway 832 ^,״׳״^ ^׳^^׳״ POLITICAL AFFAIRS a to the theory and practice of Marxism-Leninism EDITORIAL BOARD ־ V. J. JEROME, Editor ABNER W. -

Statement to the Membership of the Communist Party of America by the CEC, April 24, 1922.†

CEC: Statement to the Membership, April 24, 1922 1 Statement to the Membership of the Communist Party of America by the CEC, April 24, 1922.† A document in the Herbert Romerstein collection. The CP of A is facing a period of expansion elements which can contribute to the unification which requires the full cooperation of all vital of the Party. Communist elements for the successful develop- In voluntarily resigning from the committee ment of the American Communist movement. the withdrawing members have demonstrated a The CEC elected at the last convention [May desire for harmony in the Party ranks. They give 1921] underwent many changes during the strife way to others in order to see the various elements within the organization. This strife was the result share in the responsibility of Party leadership, and of the application of the [policies of the] Third to enable them to help strengthen and consoli- Congress of the CI.‡ During the course of the date the Party ranks. The withdrawing members application of these policies a situation has arisen will personally at the convention share fully in the within the party which caused a reawakening of responsibility of the work of the committee up to the factional spirit which for years has done incal- date. They feel that the reorganized committee, culable harm to the Party. working for the welfare of the Party and in a spirit The Party convention having been postponed of revolutionary harmony can overcome the dis- for several months in accordance with the instruc- cord in the Party ranks. The CEC feels the com- tions from the CI, we feel it to be necessary to rades who voluntarily resigned have set before the make a move to abolish this factionalism, which, membership an example of personal disinterest- if permitted to grow until the Convention would edness and Party devotion which if followed gen- seriously interfere with the success of the Party. -

Revolution and Personal Crisis: William Z. Foster, Personal Narrative, and the Subjective in the History of American Communism1

Labor History, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2002 Revolution and Personal Crisis: William Z. Foster, Personal Narrative, and the Subjective in the History of American Communism1 JAMES R. BARRETT In early 1919, the progressive novelist Mary Heaton Vorse found William Z. Foster sitting in the tiny Pittsburgh of ce where he directed the Great Steel Strike, the largest industrial con ict in the history of the U.S. up to that time. Foster remained calm and collected, sel ess in the midst of this great social movement: He is composed, con dent, unemphatic and impenetrably unruf ed. Never for a moment does Foster hasten his tempo … He seems completely without ego … He lives completely outside the circle of self, absorbed ceaselessly in the ceaseless stream of detail which confronts him … Once in a while he gets angry over the stupidity of man; then you see his quiet is the quiet of a high tension machine moving so swiftly it barely hums. He is swallowed up in the strike’s immensity. What happens to Foster does not concern him. I do not believe that he spends ve minutes in the whole year thinking of Foster or Foster’s affairs.2 This was the image Foster projected throughout his early life and the reputation by which he was known: a brilliant strategist and organizational mind, an engineer and architect of working-class movements, a dedicated militant with no apparent personal life. Certainly for any historian looking for the links between the personal and the political, Foster does not appear to be a very promising subject. -

![[Name of Collection]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7653/name-of-collection-7067653.webp)

[Name of Collection]

A Register of the Herbert Romerstein collection 1864-2011 1236 manuscript boxes, 35 oversize boxes, 17 cardfile boxes (573.2 linear feet) Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563, Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Prepared by Dale Reed 2013, Revised 2016 1 Hoover Institution Library & Archives, 2016 Herbert Romerstein collection, 1864-2011 Collection Summary Collection Title Herbert Romerstein collection, 1883-2009 Collection Number 2012C51 Collector Romerstein, Herbert collector. Extent 1235 manuscript boxes, 36 oversize boxes, 17 cardfile boxes (573.2 linear feet) Repository Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University, Stanford CA, 94305-6010 http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Abstract Pamphlets, leaflets, serial issues, studies, reports, and synopses of intelligence documents, relating to the Communist International, communism and communist front organizations in the United States, Soviet espionage and covert operations, and propaganda and psychological warfare, especially during World War II. Physical Location Hoover Institution Archives Language of the materials The collection is in English 2 Hoover Institution Library & Archives, 2016 Herbert Romerstein collection, 1864-2011 Information for Researchers Access Box 519 restricted; use copies available in Box 518. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Herbert Romerstein collection, [Box no.], Hoover Institution Archives Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 2012 with additional increments thereafter. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. -

Trotsky the Traitor

University of Central Florida STARS PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements 1-1-1937 Trotsky the traitor Alexander Bittelman Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bittelman, Alexander, "Trotsky the traitor" (1937). PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements. 496. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism/496 CONTENTS CHAPTER I Incredible but True................................... ................... .............. 3 CHAPTER II A Path of Treachery. ..........................•...................................... 12 CHAPTER fll Confessions and Objective Evidence ........................................ 18 CHAPTER IV Soviet Democracy Vindicated .................................................... 23 CHAPTER V A Menace to Progressive Mankind .......................................... 27 PUBLISHED BY WORKERS LmRARY PUBLISHERS, INC. P. O. BO.X 14R, STA. D, NE"; YORK CITY FEBRUARY, 19.37 ~209 CHAPTER I Incredible but True LENIN called Trotsky Judas-and cautioned the people repeatedly to beware of him. Today Trotsky and hie agents stand exposed before the whole world~ They stand exposed and branded as the worst Judases the world has ev~r known. 'Vorse than our own Benedict Arnold who betrayed his country men at a time of great stress and crisis. Naturally there are some who are s~ill in doubt. And, natur ally .again, Trotskyite agents seek to exploit these ' doUbts to confuse some people and, under cover of confusion, to pro mote Trotsky's horrible conspiracies. It is incredible, some people say, that Trotsky and his agents should have gone so far. -

Of Nationhood

Preface DREAMS OF NATIONHOOD American Jewish Communists and the Soviet Birobidzhan Project, 1924-1951 i A BBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS JEWISH IDENTITIES IN POST MODERN SOCIETY Series Editor: Roberta Rosenberg Farber – Yeshiva University Editorial Board: Sara Abosch – University of Memphis Geoffrey Alderman – University of Buckingham Yoram Bilu – Hebrew University Steven M. Cohen – Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion Bryan Daves – Yeshiva University Sergio Della Pergola – Hebrew University Simcha Fishbane – Touro College Deborah Dash Moore – University of Michigan Uzi Rebhun – Hebrew University Reeva Simon –Yeshiva University Chaim I. Waxman – Rutgers University ii Preface Dreams of Nationhood: American Jewish Communists and the Soviet Birobidzhan Project, 1924-1951 Henry Felix Srebrnik Boston 2010 iii List of Illustrations Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Srebrnik, Henry Felix. American Jewish communists and the Soviet Birobidzhan project, 1924-1951 / Henry Felix Srebrnik. p. cm. -- (Jewish identities in post modern society) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-936235-11-7 (hardback) 1. Jews--United States--Politics and government--20th century. 2. Jewish communists--United States--History--20th century. 3. Communism--United States--History--20th century. 4. Icor. 5. Birobidzhan (Russia)--History. 6. Evreiskaia avtonomnaia oblast (Russia)--History. I. Title. E184.J4S74 2010 973'.04924--dc22 2010024428 Copyright © 2010 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved Cover and interior design by Adell Medovoy Published by Academic Studies Press in 2010 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com iv Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. -

Gj|"| Subscription

Page Four THE DAILY WORKER Wednesday, October 29, 1924 ... ... - ■ - - * ■' *' ' < ANNIVERSARY OF RED NIGHT ON Come Over! from the D. E. C. to the N. E. C. of ! At any time during the day or evening if you have MUSSOLINI RULE September 11. RED EAST SIDE an hour to spare—come over and volunteer your help 2. The leaflet by the D. E. DECISIONS OF WORKERS PARTY issued < to enable us to get out a heap of mailing, inserting and C. also the Zam note to be criticized increase the on ground con- ! other odd jobs on the campaign to circu- CENTRAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE the that neither their the tents nor the demands are sufficiently lation of the DAILY WORKER and WORKERS SEES IT TOTTER MAKES BIG HIT I work local in their that they lack We are very busy and have loads of and 20. teaching personnel nature, MONTHLY. October 14 1. The must specific economic and political de- us over! The Central Executive Committee consist of reliable, active —help out—come com- mands and give a false formulation 15MO flew Members of the Workers Party at its sessions rades, who have demonstrated by Tremendous Crowds at v "• for slogans against capitalist mili- " our -- ! :--7 - —wwwwirw adopted by ---■ October 14 and 20 the follow- their relations to the party and tarism. -■■ Party ing decisions. their record of activity that they Each Meeting in Communist are 3. The D. E. C. should be criticized combination, who had hugged this themselves active and conscious fol- Negro Work. for having continued the controversy the afternoon (Spacial to the Daily Worker) lowers of the Communist Internation- By MARY RUBIN.