University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horizons '83, Meet the Composer, and New Romanticism's New Marketplace

Horizons ’83, Meet the Composer, and New Romanticism’s New Marketplace Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mq/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/musqtl/gdz015/5653100 by guest on 06 December 2019 William Robin The New York Philharmonic was not entirely confident about the pros- pects for a new festival dedicated entirely to contemporary music, to be mounted over two weeks in June 1983. Although more than $80,000 had been budgeted toward advertising and promotion—nearly a tenth of the festival’s total anticipated expenses––advance ticket sales had been slow, perhaps demonstrating that despite recent aesthetic shifts in new music toward styles like minimalism and neo-Romanticism, audiences still felt that contemporary composition was inaccessible, academic, or full of alienating and atonal sounds. On the first night of the festival, dubbed Horizons ’83, the Philharmonic had opened only one of its box office windows at Avery Fisher Hall. But, to everyone’s surprise, a large audi- ence soon appeared, and the queue for same-day tickets quickly stretched out into Lincoln Center’s plaza. As the Philharmonic’s composer-in-residence Jacob Druckman, who curated the Horizons festi- val, later described, “There were 1,500 people lined up around the square and we were frantically telephoning to get somebody to open up other windows.”1 Horizons ’83 was a hit. It would go on to fill Avery Fisher Hall to an average of 70 percent capacity over the festival’s six concerts: A major box office coup for contemporary music, and one com- parable to the orchestra’s ticket sales for standard fare like Beethoven or Mozart. -

Nasher Sculpture Center's Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Macke

Nasher Sculpture Center’s Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Mackey to be Performed at City Performance Hall; Guaranteed Seating with Soundings Season Ticket Package Brentano String Quartet Performance of One Red Rose, co-commissioned by the Nasher with Carnegie Hall and Yellow Barn, moved to accommodate bigger audience. DALLAS, Texas (September 12, 2013) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce that the JFK commemorative Soundings concert will be performed at City Performance Hall. Season tickets to Soundings are now on sale with guaranteed seating to the special concert honoring President Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his death with an important new work by internationally renowned composer Steven Mackey. One Red Rose is written for the Brentano String Quartet in commemoration of this anniversary, and is commissioned by the Nasher (Dallas, TX) with Carnegie Hall (New York, NY) and Yellow Barn (Putney, VT). The concert will be held on Saturday, November 23, 2013 at 7:30 pm at City Performance Hall with celebrated musicians; the Brentano String Quartet, clarinetist Charles Neidich and pianist Seth Knopp. Mr. Mackey’s One Red Rose will be performed along with seminal works by Olivier Messiaen and John Cage. An encore performance of One Red Rose, will take place Sunday, November 24, 2013 at 2 pm at the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Both concerts will include a discussion with the audience. Season tickets are now available at NasherSculptureCenter.org and individual tickets for the November 23 concert will be available for purchase on October 8, 2013. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1999, No.36

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Forced/slave labor compensation negotiations — page 2. •A look at student life in the capital of Ukraine — page 4. • Canada’s professionals/businesspersons convene — pages 10-13. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXVII HE No.KRAINIAN 36 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 1999 EEKLY$1.25/$2 in Ukraine U.S.T continues aidU to Kharkiv region W Pustovoitenko meets in Moscow with $16.5 million medical shipment by Roman Woronowycz the region and improve the life of Kharkiv’s withby RomanRussia’s Woronowycz new increasingprime Ukrainian minister debt for Russian oil Kyiv Press Bureau residents, which until now had produced Kyiv Press Bureau and gas. The disagreements have cen- few tangible results. tered on the method of payment and the KYIV – The United States government “This is the first real investment in terms KYIV – Ukraine’s Prime Minister amount. continued to expand its involvement in the of money,” said Olha Myrtsal, an informa- Valerii Pustovoitenko flew to Moscow on Ukraine has stated that it owes $1 bil- Kharkiv region of Ukraine on August 25 tion officer at the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv. August 27 to meet with the latest Russian lion, while Russia claims that the costs when it delivered $16.5 million in medical Sponsored by the Department of State, the prime minister, Vladimir Putin, and to should include money owed by private equipment and medicines to the area’s hos- humanitarian assistance program called discuss current relations and, more Ukrainian enterprises, which raises the pitals and clinics. -

Program Notes by MARTIN BOOKSPAN

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER March 24, 1999 8-10 PM New York City Opera: Lizzie Borden Program Notes by MARTIN BOOKSPAN "Lizzie Borden"- Music by Jack Beeson; libretto by Kenward Elmslie; based on a scenario by Richard Plant. World premiere given at New York City Opera, March 25, 1965. "Lizzie Borden took an ax, and gave her father forty whacks." This childhood rhyme may have passed from currency in the waning years of the twentieth century, but the event it memorialized was very much alive in the waning years of the nineteenth. Along with the likes of Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed, Lizzie Borden of Fall River, Massachusetts, assumed legendary status in the American popular imagination. In some respects the situation seems to be a remarkable parallel to one with which we are all familiar, the O.J. Simpson affair. These are the facts: on August 4, 1892, the citizens of Fall River were shaken by the brutal murder of two of its most solid citizens, Andrew Borden and his wife, Abbie Gray Borden. The finger of suspicion soon pointed to Andrew Borden's thirty-three-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, known as Lizzie, an apparently demure and reserved gentlewoman. She testified at an inquest, but thereafter refused comment, even declining to testify in her own defense at the trial that ensued. The evidence arrayed against her seemed confused and even conflicting, and many in the community could not bring themselves to believe that she was guilty. Weak testimony in her favor was offered by her sister, Emma; in the final summation, these were the words of her chief defense attorney: "To find her guilty, you must believe she is a fiend. -

2019/2020 St. Louis Symphony Orchestra Season at a Glance

2019/2020 ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEASON AT A GLANCE • Stéphane Denève begins his tenure as the 13th Music Director of the 140-year-old St. Louis Symphony Orchestra with a free concert for thousands at Forest Park’s iconic Art Hill. • The season includes three world premieres of SLSO-commissioned works by Aaron Jay Kernis, Kevin Puts, and a group of ten composers of today; the U.S. premiere of the orchestral version of Guillaume Connesson’s A Kind of Trane; 16 works by composers of today including John Adams, Lera Auerbach, William Bolcom, Anna Clyne, Guillaume Connesson, Sofia Gubaidulina, Jennifer Higdon, Pierre Jalbert, Aaron Jay Kernis, Arvo Pärt, Kevin Puts, Outi Tarkiainen, and John Williams, plus a work that includes contributions from composers Claude Baker, William Bolcom, Guillaume Connesson, John Corigliano, Truman Harris, Cindy McTee, Joseph Schwantner, Daniel Slatkin, Leonard Slatkin, and Joan Tower; 19 works that are SLSO premieres; and numerous works that have been given rare performance by the SLSO. • The SLSO’s recently announced 19/20 Live at the Pulitzer series immerses audiences at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in multimedia solo and chamber ensemble performances, including two world premieres by Susan Philipsz and Christopher Stark, as well as works by John Luther Adams, Christopher Cerrone, Phyllis Chen, Danny Clay, Brett Dean, Yotam Haber, Carolina Heredia, David Lang, Missy Mazzoli, Annika Socolofsky, and LJ White. • Denève’s close collaborator and celebrated pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet joins the SLSO as the Jean-Paul and Isabelle Montupet Artist-in-Residence, performing works by Ravel, Liszt, and Connesson with the orchestra, plus an evening of chamber music at Washington University in St. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

50Th Annual Concerto Concert

SCHOOL OF ART | COLLEGE OF MUSICAL ARTS | CREATIVE WRITING | THEATRE & FILM BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY 50th a n n u a l c o n c e r t o concert BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY Summer Music Institute 2017 bgsu.edu/SMI featuring the SESSION ONE - June 11-16 bowling g r e e n Double Reed Strings philharmonia SESSION TWO - June 18-23 emily freeman brown, conductor Brass Recording Vocal Arts SESSION THREE - June 25-30 Musical Theatre saturday, february 25 Saxophone 2017 REGISTRATION OPENS FEBRUARY 1ST 8:00 p.m. For more information, visit BGSU.edu/SMI kobacker hall BELONG. STAND OUT. GO FAR. CHANGING LIVES FOR THE WORLD.TM congratulations to the w i n n e r s personnel of the 2016-2 017 Violin I Bass Trombone competition in music performance Alexandria Midcalf** Nicholas R. Young* Kyle McConnell* Brandi Main** Lindsay W. Diesing James Foster Teresa Bellamy** Adam Behrendt Jef Hlutke, bass Mary Solomon Stephen J. Wolf Morgan Decker, guest Ling Na Kao Cameron M. Morrissey Kurtis Parker Tuba Jianda Bai Flute/piccolo Diego Flores La Le Du Alaina Clarice* undergraduate - performance Nia Dewberry Samantha Tartamella Percussion/ Timpani Anna Eyink Michelle Whitmore Scott Charvet* Stephen Dubetz, clarinet Keisuke Kimura Jerin Fuller+ Elijah T omas Oboe/Cor Anglais Zachary Green+ Michelle Whitmore, flute Jana Zilova* Febe Harmon Violin II T omas Morris David Hirschfeld+ Honorable Mention: Samantha Tartamella, flute Sophia Schmitz Mayuri Yoshii Erin Reddick+ Bethany Holt Anthony Af ul Felix Reyes Zi-Ling Heah Jamie Maginnis Clarinet/Bass clarinet/ Harp graduate - performance Xiangyi Liu E-f at clarinet Michaela Natal Lindsay Watkins Lucas Gianini** Keyboard Kenneth Cox, flute Emily Topilow Hayden Giesseman Paul Shen Kyle J. -

Red Note New Music Festival Program, 2013 School of Music Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Red Note New Music Festival Music 2013 Red Note New Music Festival Program, 2013 School of Music Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/rnf Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation School of Music, "Red Note New Music Festival Program, 2013" (2013). Red Note New Music Festival. 7. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/rnf/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Red Note New Music Festival by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. calendar of events SUNDAY, MARCH 3, 2013 3 PM COMPOSER PRESENTATION CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS David Kirkland Garner centennial east building, room 229 2 - 2:50 pm the illinois state university wind symphony, conducted by daniel belongia, performs music composer david kirkland garner, winner of the by scott lindroth, john mackey, and paul dooley, composition competition, presents on his music as well as marcus maroney’s “rochambeau” (winner of the red note call for scores). COMPOSER Q&A - Tony Solitro MONDAY, MARCH 4, 2013 2-4 PM Kemp Recital Hall 4 - 5:30 pm KEMP RECITAL HALL composer tony solitro discusses his vocal music and career as a composer of opera and songs chicago-based spektral quartet leads a master class for string students in the illinois state university school of music string studio. TUESDAY, MARCH 5, 2013 8 PM KEMP RECITAL HALL MONDAY, MARCH 4, 2013 8 PM KEMP RECITAL HALL illinois state university faculty members and guest pianist blair mcmillen perform works of guest composer joan tower. -

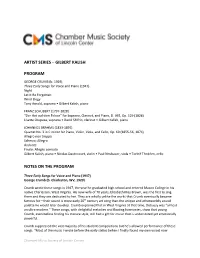

Artist Series – Gilbert Kalish Program Notes

ARTIST SERIES – GILBERT KALISH PROGRAM GEORGE CRUMB (b. 1929) Three Early Songs for Voice and Piano (1947) Night Let It Be Forgotten Wind Elegy Tony Arnold, soprano • Gilbert Kalish, piano FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) “Der Hirt auf dem Felsen” for Soprano, Clarinet, and Piano, D. 965, Op. 129 (1828) Lisette Oropesa, soprano • David Shifrin, clarinet • Gilbert Kalish, piano JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Quartet No. 3 in C minor for Piano, Violin, Viola, and Cello, Op. 60 (1855-56, 1874) Allegro non troppo Scherzo: Allegro Andante Finale: Allegro comodo Gilbert Kalish, piano • Nicolas Dautricourt, violin • Paul Neubauer, viola • Torleif Thedéen, cello NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Three Early Songs for Voice and Piano (1947) George Crumb (b. CHarleston, WV, 1929) Crumb wrote these songs in 1947, the year he graduated high school and entered Mason College in his native Charleston, West Virginia. His now-wife of 70 years, Elizabeth May Brown, was the first to sing them and they are dedicated to her. They are wholly unlike the works that Crumb eventually became famous for—their sound is more early 20th century art song than the unique and otherworldly sound palette he would later develop. Crumb explained that in West Virginia at that time, Debussy was “almost an ultra-modern.” These songs, with delightful melodies and floating harmonies, show that young Crumb, even before finding his mature style, still had a gift for music that is understated yet emotionally powerful. Crumb suppressed the vast majority of his student compositions but he’s allowed performance of these songs. “Most of the music I wrote before the early sixties (when I finally found my own voice) now Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center causes me intense discomfort,” he writes, “although I make an exception for a few songs which I composed when I was 17 or 18.… these little pieces stayed in my memory and when, some years ago, Jan DeGaetani expressed an interest in seeing them (with a view to possible performance if she liked them), I made a few slight revisions and even decided to have them published. -

Irish Travelling Artists: Ireland, Southern Asia and the British Empire 1760-1850

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Irish Travelling Artists: Ireland, Southern Asia and the British Empire 1760-1850 Thesis How to cite: Mcdermott, Siobhan Clare (2019). Irish Travelling Artists: Ireland, Southern Asia and the British Empire 1760-1850. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2018 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000ed14 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Irish Travelling Artists: Ireland, Southern Asia and the British Empire 1760-1850 Siobhan Claire McDermott, BA, MA, Open University, MB, BAO, BCh, Trinity College Dublin. Presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, School of Arts and Culture, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, the Open University, September, 2018. Personal Statement No part of this thesis has previously been submitted for a degree or other qualification of the Open University or any other university or institution. It is entirely the work of the author. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to show that Irish art made in the period under discussion, the late-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, should not be considered solely in terms of Ireland’s relationship with England as heretofore, but rather, within the framework of the wider British Empire. -

Paul Schoenfield's' Refractory'method of Composition: a Study Of

Paul Schoenfield's 'Refractory' Method of Composition: A Study of Refractions and Sha’atnez A document submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by DoYeon Kim B.M., College-Conservatory of Music of The University of Cincinnati, 2011 M.M., Eastman School of Music of The University of Rochester, 2013 Committee Chair: Professor Yehuda Hanani Abstract Paul Schoenfield (b.1947) is a contemporary American composer whose works draw on jazz, folk music, klezmer, and a deep knowledge of classical tradition. This document examines Schoenfield’s characteristic techniques of recasting and redirecting preexisting musical materials through diverse musical styles, genres, and influences as a coherent compositional method. I call this method ‘refraction’, taking the term from the first of the pieces I analyze here: Refractions, a trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano written in 2006, which centers on melodies from Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). I will also trace the ‘refraction’ method through Sha’atnez, a trio for Violin, Cello and Piano (2013), which is based on two well-known melodies: “Pria ch’io l’impegno” from Joseph Weigl’s opera L’amor marinaro, ossia il corsaro (also known as the “Weigl tune,” best known for its appearance in the third movement of Beethoven’s Trio for Piano, Clarinet, and Cello in B-flat Major, Op.11 (‘Gassenhauer’)); and the Russian-Ukrainian folk song “Dark Eyes (Очи чёрные).” By tracing the ‘refraction’ method as it is used to generate these two works, this study offers a unified approach to understanding Schoenfield’s compositional process; in doing so, the study both makes his music more accessible for scholarly examination and introduces enjoyable new works to the chamber music repertoire. -

Henry Brant on the Birth of Angels and Devils by Nancy Toff

The New York Flute Club N E W S L E T T E R March 2003 A Conversation With Robert Aitken Interview by Patti Monson Patti Monson spoke with Robert Aitken by phone in January. ATTI MONSON: Could you tell us often looking for works to play with instru- about some of your most recent ments besides piano. Then there are my Pcompositions? two [1977] solo flute pieces Plainsong ROBERT AITKEN: The last work and Icicle which are quite often played, [Shadows V, a concerto for flute and and may in fact become contemporary strings, 1999] was a commission for the flute classics. From time to time Plain- Chamber Orchestra of Neuchâtel [Switzer- song is a required piece in flute contests land]. They specifically wanted a work and Icicle is often a required work for related to native peoples. At first I had entrance to French music schools. little interest in doing exactly that, but Of course extended techniques are eventually I became fascinated with the used in all these pieces, but in an unpre- idea. I think it came off rather well. It is tentious, rather natural way. I hope that not an imitation of western Indian music all are playable on every flute. Of course In Concert but the inspiration for the work came one runs into trouble if a composition is from what I had learned about the music intended for a flute with B foot and the ROBERT AITKEN, flute several years ago. It is quite a long piece, flutist does not have one. But I am really PHOTO: JOHNPHOTO: SHAW Colette Valentine, piano some 22 minutes in length, [but it] seems not very upset if a practical solution is Saturday, March 29, 2003, to hold the attention of the audience.