Maltese Language in Education in Malta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sicilian Revolution of 1848 As Seen from Malta

The Sicilian Revolution of 1848 as seen from Malta Alessia FACINEROSO, Ph.D. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Following the Sicilian revolution of 1848, many italian intellectuals and politicalfiguresfound refuge in Malta where they made use ofthe Freedom ofthe Press to divulge their message ofunification to the mainland. Britain harboured hopes ofseizing Sicily to counterbalance French expansion in the Mediterranean and tended to support the legitimate authority rather than separatist ideals. Maltese newspapers reflected these opposing ideas. By mid-1849 the revolution was dead. Keywords: 1848 Sicilian revolution, Italian exiles, Freedom of the Press, Maltese newspapers. The outbreak of Sicilian revolution of 12 January 1848 was precisely what everyone in Malta had been expecting: for months, the press had followed the rebellious stirrings, the spread of letters and subversive papers, and the continuous movements of the British fleet in Sicilian harbours. A huge number of revolutionaries had already found refuge in Malta, I escaping from the Bourbons and anxious to participate in their country's momentous events. During their stay in the island, they shared their life experiences with other refugees; the freedom of the press that Malta obtained in 1839 - after a long struggle against the British authorities - gave them the possibility to give free play to audacious thoughts and to deliver them in writing to their 'distant' country. So, at the beginning of 1848, the papers were happy to announce the outbreak of the revolution: Le nOlizie che ci provengono dalla Sicilia sono consolanti per ta causa italiana .... Era if 12 del corrente, ed il rumore del cannone doveva annunziare al troppo soflerente papalo siciliano it giorno della nascifa def suo Re. -

The Process of Teacher Education for Inclusion: The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs · Volume 10 · Number s1 · 2010 139–148 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01163.x The process of teacher education for inclusion: the Maltese experiencejrs3_1163 139..148 Paul A. Bartolo University of Malta, Malta Key words: Social inclusion, inclusive education, teacher education, pedagogy, inclusive development. The gradual development of inclusive education can be This paper discusses major challenges for the traced to the introduction of compulsory primary education development of teacher education for inclusion for all children from age 5 through 14 years in 1946, which through an analysis of relevant recent experience in was fully implemented by the early 1950s. Despite Malta’s Malta. Inclusion in society and in education has long cultural history extending to at least 5000 bc and the been explicitly on the Maltese national agenda for existence of the University of Malta for over 400 years, it the past two decades. The Faculty of Education of the University of Malta has been one of the main was the introduction of compulsory education that led to the actors of the inclusion initiative and has also first attempts to ensure that no children were prevented from taken a European initiative through the recent access to public education (Bartolo, 2001). co-ordination of a seven-country, 3-year European The idea of education as a need and right for all was further Union Comenius project on preparing teachers for responding to student diversity. -

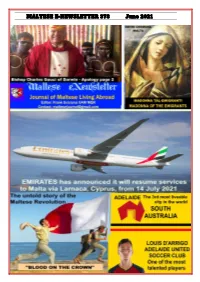

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 Aboriginal survivors reach settlement with Church, Commonwealth cathnew.com Survivors of Aboriginal forced removal policies have signed a deal for compensation and apology 40 years after suffering sexual and physical abuse at the Garden Point Catholic Church mission on Melville Island, north of Darwin. Source: ABC News. “I’m happy, and I’m sad for the people who have gone already … we had a minute’s silence for them … but it’s been very tiring fighting for this for three years,” said Maxine Kunde, the leader Mgr Charles Gauci - Bishop of Darwin of a group of 42 survivors that took civil action against the church and Commonwealth in the Northern Territory Supreme Court. At age six, Ms Kunde, along with her brothers and sisters, was forcibly taken from her mother under the then-federal government’s policy of removing children of mixed descent from their parents. Garden Point survivors, many of whom travelled to Darwin from all over Australia, agreed yesterday to settle the case, and Maxine Kunde (ABC News/Tiffany Parker) received an informal apology from representatives of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, in a private session.Ms Kunde said members of the group were looking forward to getting a formal public apology which they had been told would be delivered in a few weeks’ time. Darwin Bishop Charles Gauci said on behalf of the diocese he apologised to those who were abused at Garden Point. -

The Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty

4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature By Olivia Snaije July 24, 2017 Wit (13) Besides the fact that it’s a beautiful island in the middle of the Mediterranean, how much do we really know about Malta? You may remember it's where the Knights of Malta spent some time between the 16th and the 18th century. Comic book https://www.bookwitty.com/text/malta-the-struggle-to-preserve-language-and/596f7cb050cef766f8f236ab 1/11 4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty aficionados will be familiar with the fact that Joe Sacco was born in Malta. But did you know, for example, that in 2018 the island will be the European Capital of Culture? Or that every August a literature festival is held there? And that three Maltese authors, Immanuel Mifsud, Pierre J. Mejlak, and Walid Nabhan recently won the European Prize for Literature? The language they write in, of course, is Maltese, which is derived from an Arabic dialect that was spoken in Sicily and Spain during the Middle Ages. It sounds like Arabic with a smattering of Italian and English thrown in, and it is written in Latin script, making it the only Semitic language to be inscribed this way. A page from Il Cantilena https://www.bookwitty.com/text/malta-the-struggle-to-preserve-language-and/596f7cb050cef766f8f236ab 2/11 4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty A 15th century poem called “Il Cantilena”, by Petrus Caxaro is the earliest written document in Maltese that has been preserved. -

Desk Research Report

EDUCATION FOR ALL Special Needs and Inclusive Education in Malta Annex 2: Desk Research Report EUROPEAN AGENCY for Special Needs and Inclusive Education EDUCATION FOR ALL Special Needs and Inclusive Education in Malta Annex 2: Desk Research Report European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education ANNEX 2: DESK RESEARCH REPORT Contents Introduction................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ............................................................................................................ 3 Context ..................................................................................................................... 3 1. Legislation and policy............................................................................................... 5 International normative instruments ....................................................................... 5 EU policy guidelines.................................................................................................. 7 National policy.......................................................................................................... 8 Conceptions of inclusion ........................................................................................... 9 Consistency of policies............................................................................................ 11 Inter Ministerial work ............................................................................................. 12 Summary -

Researching Early Childhood Education: Voices from Malta

Researching Early Childhood Education: Voices from Malta Researching Early Childhood Education: Voices from Malta Editors: Peter Clough, Cathy Nutbrown, Jools Page University of Sheffield. School of Education Editorial Assistant : Karen Kitchen University of Sheffield. School of Education Cover image: Sue Mifsud Midolo St Catherine’s High School, Pembroke, Malta © 2012 The University of Sheffield and individual authors The University of Sheffield, School of Education, 388 Glossop Road, Sheffield, S10 2JA, UK email: [email protected] ii © 2012 The University of Sheffield and individual authors Researching Early Childhood Education: Voices from Malta Researching Early Childhood Education: Voices from Malta CONTENTS Preface Professor Valerie Sollars iv A note from the editors vi About the authors vii PART 1 CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES 2 Revisiting my childhood: reflections on life choices Vicky Bugeja 3 Are you listening to me? Young children’s views of their childcare Karen Abela 21 setting Moving on to First grade: two children’s experiences Marvic Friggieri 40 “…And she appears to be invisible…” Imaginary companions and Christina Pace 58 children’s creativity Two of a kind?: A baby with Down Syndrome and his typically Laura Busuttil 75 developing twin. Living with Asthma at home and school Claire Grech 101 PART II LITERACY HOME AND SCHOOL 131 Five Maltese Mothers talk about their role in children’s early literacy Caroline Bonavia 132 development The impact of the home literacy environment on a child’s literacy Maria Camilleri 153 development -

A Literary Translation in the Making

A LITERARY TRANSLATION IN THE MAKING An in-depth investigation into the process of a literary translation from French into Maltese CLAUDINE BORG Doctor of Philosophy ASTON UNIVERSITY October 2016 © Claudine Borg, 2016 Claudine Borg asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this thesis This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without appropriate permission or acknowledgement. 1 ASTON UNIVERSITY Title: A literary translation in the making: an in-depth investigation into the process of a literary translation from French into Maltese Name: Claudine Borg Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Date: 2016 Thesis summary: Literary translation is a growing industry with thousands of texts being published every year. Yet, the work of literary translators still lacks visibility and the process behind the emergence of literary translations remains largely unexplored. In Translation Studies, literary translation was mostly examined from a product perspective and most process studies involved short non- literary texts. In view of this, the present study aims to contribute to Translation Studies by investigating in- depth how a literary translation comes into being, and how an experienced translator, Toni Aquilina, approached the task. It is particularly concerned with the decisions the translator makes during the process, the factors influencing these and their impact on the final translation. This project places the translator under the spotlight, centring upon his work and the process leading to it while at the same time exploring a scantily researched language pair: French to Maltese. -

Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta

Vol:1 No.1 2003 96-118 www.educ.um.edu.mt/jmer Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta George Cassar [email protected] George Cassar holds the post of lecturer with the University of Malta. He is Area Co- ordinator for the Humanities at the Junior College where he is also Subject Co-ordinator in- charge of the Department of Sociology. He holds degrees from the University of Malta, obtaining his Ph.D. with a thesis entitled Prelude to the Emergence of an Organised Teaching Corps. Dr. Cassar is author of a number of articles and chapters, including ‘A glimpse at private education in Malta 1800-1919’ (Melita Historica, The Malta Historical Society, 2000), ‘Glimpses from a people’s heritage’ (Annual Report and Financial Statement 2000, First International Merchant Bank Ltd., 2001) and ‘A village school in Malta: Mosta Primary School 1840-1940’ (Yesterday’s Schools: Readings in Maltese Educational History, PEG, 2001). Cassar also published a number of books, namely, Il-Mużew Marittimu Il-Birgu - Żjara edukattiva għall-iskejjel (co-author, 1997); Għaxar Fuljetti Simulati għall-użu fit- tagħlim ta’ l-Istorja (1999); Aspetti mill-Istorja ta’ Malta fi Żmien l-ingliżi: Ktieb ta’ Riżorsi (2000) (all Għaqda ta’ l-Għalliema ta’ l-Istorja publications); Ġrajja ta’ Skola: L-Iskola Primarja tal-Mosta fis-Sekli Dsatax u Għoxrin (1999) and Kun Af il-Mosta Aħjar: Ġabra ta’ Tagħlim u Taħriġ (2000) (both Mosta Local Council publications). He is also researcher and compiler of the website of the Mosta Local Council launched in 2001. Cassar is editor of the journal Sacra Militia published by the Sacra Militia Foundation and member on The Victoria Lines Action Committee in charge of the educational aspects. -

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 329 July 2020

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 329 July 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 329 July 2020 FRANK SCICLUNA RETIRES… I WOULD LIKE INFORM MY READERS that I am retiring from the office of honorary consul for Malta in South Australia after 17 years of productive and sterling work for the Government of the Republic of Malta. I feel it is the appropriate time to hand over to a new person. I was appointed in May 2003 and during my time as consul I had the privilege to work with and for the members of the Maltese community of South Australia and with all the associations and especially with the Maltese Community Council of SA. I take this opportunity to sincerely thank all my friends and all those who assisted me in my journey. My dedication and services to the community were acknowledged by both the Australian and Maltese Governments by awarding me with the highest honour – Medal of Order of Australia and the medal F’Gieh Ir-Repubblika, which is given to those who have demonstrated exceptional merit in the service of Malta or of humanity. I thank also the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Evarist Bartolo, for acknowledging my continuous service to the Government of the Republic of Malta. I plan to continue publishing this Maltese eNewsletter – the Journal of Maltese Living Abroad which is the most popular and respected journal of the Maltese Diaspora and is read by thousands all over the world. I will publish in my journal the full story of this item in the near future. MS. CARMEN SPITERI On 26 June 2020 I was appointed as the Honorary Consul for Malta in South Australia. -

Influence of National Culture on Diabetes

Influence of national culture on diabetes education in Malta: A case example Cynthia Formosa, Kevin Lucas, Anne Mandy, Carmel Keller Article points Diabetes is a condition of particular importance to the 1. This study aimed to Maltese population. Currently, 10% of the Maltese population explore whether or has diabetes, compared with 2–5% of the population in not diabetes education the majority of Malta’s neighbouring European nations improved knowledge, HbA1c and cholesterol (Rocchiccioli et al, 2005). The high prevalence of diabetes levels in Maltese people results in nearly one out of every four deaths of Maltese people with type 2 diabetes. occurring before the age of 65 years (Cachia, 2003). In this 2. There was no difference article we explore the possible contributions of the unique between the intervention and control groups in Maltese culture to the epidemiology, we hope that some lessons any of the metabolic can be taken when attempting educational interventions in parameters. people of differing backgrounds. 3. Sophisticated programmes that take account of the unique nature of Maltese culture are necessary to he reasons why Malta has such a high living conditions started to improve for ordinary bring about behavioural incidence and prevalence of diabetes Maltese people (Savona-Ventura, 2001). and metabolic changes in are complex. The Maltese population Extensive social disruption was brought this group. T Key words is the result of the inter-marrying between about by lengthy blockades that occurred peoples of the various cultures and nations during the Second World War, resulting in - Education that have occupied the island through the ages. -

~~He Journal of the Faculty of Education University of Malta

1995 VOLUMES N0.3 ~~he Journal of The Faculty of Education University of Malta , EDUCATION The Journal of the Faculty of Education University of Malta Vol. 5 No 3 1995 Special Issue: Architecture and Schooling. Editorial Board COPYRIGHT Editor The articles and information in EDUCATION are R.G. Sultana copyright material. Guest Co-editor: J. Falzon OPINIONS Members M. Borg Opinions expressed in this journal are those of those D. Chetcuti of the authors and need not necessarily reflect those M. Sant of the Faculty of Education or the Editorial Board. V. Sollars Cover design: Scan via Setting: Poulton's Print Shop Ltd Printing: Poulton's Print Shop Ltd ISSN No: 1022-551X INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS quotations should form separate, indented and single Education is published twice yearly as the spaced paragraphs. Notes and references must be journal of the Faculty of Education at the University numbered and the bibliography at the end should of Malta. contain the following: The editorial board welcomes articles that a) Authors' surnames and initials; contribute to a broad understanding of educational b) Year of Publication; issues, particularly those related to Malta. c) Title of Publication; d) Place of Publication; Submitted articles are referred at least once and e) Publishers. copies of referees' comments will be sent to the author as appropriate. The editors reserve the right to make Authors should submit brief biographical details editorial changes in all manuscripts to improve clarity with the article. and to conform to the style of the journal. Photographs, drawings, cartoons and other illustrations are welcome; however authors are responsible for obtaining written Communications should be addressed to: permission and copyright release when required. -

THE LANGUAGE QUESTION in MALTA - the CONSCIOUSNESS of a NATIONAL IDENTITY by OLIVER FRIGGIERI

THE LANGUAGE QUESTION IN MALTA - THE CONSCIOUSNESS OF A NATIONAL IDENTITY by OLIVER FRIGGIERI The political and cultural history of Malta is largely determined by her having been a colony, a land seriously limited in her possibilities of acquiring self consciousness and of allowing her citizens to live in accordance with their own aspirations. Consequently the centuries of political submission may be equally defined as an uninterrupted experience of cultural submission. In the long run it has been a benevolent and fruitful submission. But culture, particularly art, is essentially a form of liberation. Lack of freedom in the way of life, therefore, resulted in lack of creativity. Nonetheless her very insularity was to help in the formation of an indigenous popular culture, segregated from the main foreign currents, but necessarily faithful to the conditions of the simple life of the people, a predominantly rural anrl nilioio115 life taken up by preoccupations of a subdued rather than rebellious nature, concerned with the family rather than with the nation. The development of the two traditional languages of Malta - the Italian language, cultured and written, and the Maltese, popular and spoken - can throw some light on this cultural and social dualism. The geographical position and the political history of the island brought about a very close link with Italy. In time the smallness of the island found its respectable place in the Mediterranean as European influence, mostly Italian, penetrated into the country and, owing to isolation, started to adopt little by little the local original aspects. The most significant factor of this phenomenon is that Malta created a literary culture (in its wider sense) written in Italian by the Maltese themselves.