The Tethered Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visit Inspiration Guide 2017

VISIT INSPIRATION GUIDE 2017 PLEASANTON LIVERMORE DUBLIN DANVILLE Discover Everything The Tri-Valley Has To Offer 2 1 4 5 6 Daytripping in Danville Dublin—Have Fun in Our Backyard Discover Danville’s charming historical downtown. Enjoy the While You’re Away From Yours variety of shops, boutiques, restaurants, cafés, spas, wine Explore our outstanding, family-friendly amenities, including bars, museums, galleries, parks and trails. Start at Hartz and our gorgeous parks (our new aquatic center, “The Wave,” Prospect Avenue-the heart of downtown. You’ll fnd plenty opens in late spring 2017) and hiking trails, quality shopping, of free parking, and dogs are welcome, making Danville the wonderful international cuisine, an iMax theater, Dublin Ranch perfect day trip destination. Visit our website to plan your Robert Trent Jones Jr. golf course, bowling, laser tag, ice upcoming adventure through Danville, and for the historic skating, and a trampoline park. Also, join us for our signature walking tour map of the area. Once you visit Danville we know St. Patrick’s Day Festival. It’s all right here in our backyard. you’ll be back. Visit dublin.ca.gov Visit ShopDanvilleFirst.com Discover Everything The Tri-Valley Has To Offer 3 7 8 Living It Up in Livermore Pleasanton— Livermore is well known for world-class innovation, rich An Extraordinary Experience western heritage, and a thriving wine industry. Enjoy 1,200 acres of parks and open space, 24 miles of trails We offer a wide variety of shopping and dining options— and a round of golf at award-winning Callippe Preserve. -

Incandescent: Light Bulbs and Conspiracies1

Dr Grace Halden recently completed her PhD at Birkbeck, University of London. Her doctoral research on science fiction brings together her interest in philosophy, technology and literature. She has a range of diverse VOLUME 5 NUMBER 2 SPRING 2015 publications including an edited book Concerning Evil and articles on Derrida and Doctor Who. [email protected] Article Incandescent: 1 Light Bulbs and Conspiracies Grace Halden / __________________________________________ Light bulbs are with us every day, illuminating the darkness or supplementing natural light. Light bulbs are common objects with a long history; they seem innocuous and easily terminated with the flick of a switch. The light bulb is an important invention that, as Roger Fouquet notes, was transformational with regard to industry, economy and the revolutionary ability to ‘live and work in a well-illuminated environment’.2 Wiebe Bijker, in Of Bicycles, Bakelites and Bulbs (1997), explains that light bulbs show an integration between technology and society and how these interconnected advancements have led to a sociotechnical evolution.3 However, in certain texts the light bulb has been portrayed as insidious, controlling, and dehumanising. How this everyday object has been curiously demonised will be explored here. Through looking at popular cultural conceptions of light and popular conspiracy theory, I will examine how the incandescent bulb has been portrayed in dystopian ways.4 By using the representative texts of The Light Bulb Conspiracy (2010), The X-Files (1993-2002), and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), I will explore how this commonplace object has been used to symbolise the malevolence of individuals and groups, and the very essence of technological development itself. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

The Safeguards of Privacy Federalism

THE SAFEGUARDS OF PRIVACY FEDERALISM BILYANA PETKOVA∗ ABSTRACT The conventional wisdom is that neither federal oversight nor fragmentation can save data privacy any more. I argue that in fact federalism promotes privacy protections in the long run. Three arguments support my claim. First, in the data privacy domain, frontrunner states in federated systems promote races to the top but not to the bottom. Second, decentralization provides regulatory backstops that the federal lawmaker can capitalize on. Finally, some of the higher standards adopted in some of the states can, and in certain cases already do, convince major interstate industry players to embed data privacy regulation in their business models. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: US PRIVACY LAW STILL AT A CROSSROADS ..................................................... 2 II. WHAT PRIVACY CAN LEARN FROM FEDERALISM AND FEDERALISM FROM PRIVACY .......... 8 III. THE SAFEGUARDS OF PRIVACY FEDERALISM IN THE US AND THE EU ............................... 18 1. The Role of State Legislatures in Consumer Privacy in the US ....................... 18 2. The Role of State Attorneys General for Consumer Privacy in the US ......... 28 3. Law Enforcement and the Role of State Courts in the US .................................. 33 4. The Role of National Legislatures and Data Protection Authorities in the EU…….. .............................................................................................................................................. 45 5. The Role of the National Highest Courts -

A Model Regime of Privacy Protection

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2006 A Model Regime of Privacy Protection Daniel J. Solove George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel J. Solove & Chris Jay Hoofnagle, A Model Regime of Privacy Protection, 2006 U. Ill. L. Rev. 357 (2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOLOVE.DOC 2/2/2006 4:27:56 PM A MODEL REGIME OF PRIVACY PROTECTION Daniel J. Solove* Chris Jay Hoofnagle** A series of major security breaches at companies with sensitive personal information has sparked significant attention to the prob- lems with privacy protection in the United States. Currently, the pri- vacy protections in the United States are riddled with gaps and weak spots. Although most industrialized nations have comprehensive data protection laws, the United States has maintained a sectoral approach where certain industries are covered and others are not. In particular, emerging companies known as “commercial data brokers” have fre- quently slipped through the cracks of U.S. privacy law. In this article, the authors propose a Model Privacy Regime to address the problems in the privacy protection in the United States, with a particular focus on commercial data brokers. Since the United States is unlikely to shift radically from its sectoral approach to a comprehensive data protection regime, the Model Regime aims to patch up the holes in ex- isting privacy regulation and improve and extend it. -

The Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Privacy in the Coming Decade

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 2007 The Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Privacy in the Coming Decade Joseph Turow University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Chris Hoofnagle UC Berkeley School of Law, Berkeley Center for Law and Technology Deirdre K. Mlligan Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic and the Clinical Program at the Boalt Hall School of Law Nathaniel Good School of Information at the University of California, Berkeley Jens Grossklags School of Information at the University of California, Berkeley Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Turow, J., Hoofnagle, C., Mulligan, D., Good, N., and Grossklags, J. (2007-08). The Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Privacy in the Coming Decade, I/S: A Journal Of Law And Policy For The Information Society, 724-749. This article originally appeared as a paper presented under the same title at the Federal Trade Commission Tech- ade Workshop on November 8, 2006. The version published here contains additional information collected during a 2007 survey. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/520 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Privacy in the Coming Decade Abstract The large majority of consumers believe that the term “privacy policy” describes a baseline level of information practices that protect their privacy. In short, “privacy,” like “free” before it, has taken on a normative meaning in the marketplace. When consumers see the term “privacy policy,” they believe that their personal information will be protected in specific ways; in particular, they assume that a website that advertises a privacy policy will not share their personal information. -

Recommendations for Businesses and Policymakers Ftc Report March 2012

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BUSINESSES AND POLICYMAKERS FTC REPORT FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION | MARCH 2012 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BUSINESSES AND POLICYMAKERS FTC REPORT MARCH 2012 CONTENTS Executive Summary . i Final FTC Privacy Framework and Implementation Recommendations . vii I . Introduction . 1 II . Background . 2 A. FTC Roundtables and Preliminary Staff Report .......................................2 B. Department of Commerce Privacy Initiatives .........................................3 C. Legislative Proposals and Efforts by Stakeholders ......................................4 1. Do Not Track ..............................................................4 2. Other Privacy Initiatives ......................................................5 III . Main Themes From Commenters . 7 A. Articulation of Privacy Harms ....................................................7 B. Global Interoperability ..........................................................9 C. Legislation to Augment Self-Regulatory Efforts ......................................11 IV . Privacy Framework . 15 A. Scope ......................................................................15 1. Companies Should Comply with the Framework Unless They Handle Only Limited Amounts of Non-Sensitive Data that is Not Shared with Third Parties. .................15 2. The Framework Sets Forth Best Practices and Can Work in Tandem with Existing Privacy and Security Statutes. .................................................16 3. The Framework Applies to Offline As Well As Online Data. .........................17 -

Acquisition of a Majority Stake in Canyon

Acquisition of a majority stake in Canyon December 2020 2 Letter from the founder “When I saw our first bike on the Tour de France, a childhood dream came true, however, I knew that this was just the beginning. CANYON is built on a foundation of passion and self-sacrifice, with the ultimate goal of being the best bicycle company in the world. In the beginning, a lot of people told us that selling bikes online was impossible. We have proven everybody wrong! We are pioneers in building a fundamentally superior business model and consumer experience which our competitors simply can’t replicate. Our brand today represents the same core values of performance, innovation, community and quality as it did in 1985. This has only been possible thanks to our team. Always passionate, industry-leading and driven by the same goal, building the best and sharing the passion. We are uniquely positioned to take advantage of this huge and growing market with ever more support from recent global events. Our plan will take us to €1bn in sales over the next five years, but our vision remains the same. Canyon is the best bicycle company in the world. We invite GBL to join us as we become the largest.” - Roman Arnold, Founder & Chairman of the Advisory Board 3 Canyon is in line with structural trends which guide GBL’s investment decisions Health awareness Consumer experience Digitalization & technology Sustainability and resource scarcity 4 Introduction to the transaction • GBL has signed a definitive agreement to acquire a majority stake in Canyon • Canyon is -

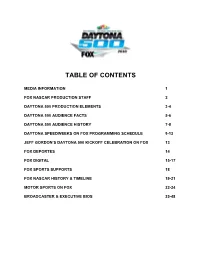

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

Saturday, March 2Nd, 2019

St. John the Baptist School Presents Saturday, March 2nd, 2019 Rock Garden Banquet & Conference Center - Green Bay, WI Doors Open at 5 pm Thank you to our Corporate Sponsors! Welcome! Welcome to the St. John the Baptist School Auction! In 1888, our parish community started St. Leo Catholic School. Thanks to the service of many lay people and religious communities, our school continues and is stronger than ever. These people made a tremendous sacrifice of time, talent and treasure. They did so because they believed in strong academics, but more importantly, that our Catholic faith must be an integral part of raising children. Saint Leo Catholic School is now named St. John the Baptist School and we are proud to continue the great legacy our forefathers handed onto us. Today, our parents and parish community continue to make many sacrifices to make Catholic education possible in our parish. Many second, third and fourth generation families walk our halls, pray in and for our school and contribute financially toward the school’s continued success ensuring our faith community continues to grow and welcome new families. Together we make local Catholic education possible. We work to maintain an environment that nurtures strong faith, fosters academic excellence, and encourages vibrant family life. The work and sacrifices we make together plant the seeds of faith in our young people. Thank you for attending our school and thank you for your financial support of our school. In Christ, Andrew Mulloy Principal 1 St. John the Baptist School Mission Statement St. John the Baptist School provides an education that is centered in Jesus Christ and on the Gospel Values through the intercession of St. -

Bartenders' Manual

BARTENDERS' MANUAL Harry Johnson, the "DEAN" of Bartend- ers, published this original manual about 1 860. This complete guide for mixing drinks and running a successful bar was the authoritative manual when drinking was an art. The prices shown in this revised edition are Harry's own Ñou of date to be sure-the recipes, how- ever, we vouch for. Some brands mentioned are now not obtainable-substitute modem brands. THE PUBLISHER. THE NEW AND IMPROVED ILLUSTRATED BARTENDERS' MANUAL OR: HOW TO MIX DRINKS OF THE PRESENT STYLE, Containing Valuable Instructions and Hints by the Author in Reference to the Management of a Bar, a Hotel and a Restau- rant; also a Large List of Mixed Drinks, including American, British, French, German, Italian, Russian, Spanish, etc., with Illustrations and a Compre- hensive Description of Bar Utensils, Wines, Liquors, Ales, Mixtures, etc , etc. 1934 REVISED EDITION. CHARLES E. GRAHAM & CO. NEWARK, N. J. MADE IN U. S. A. PREFACE BY THE AUTHOR In submitting tins manual to the public, I crave in- dulgence for making a few remarks in regard to my- self. Copyright 1934 by Charles E. Graham & Co. The profession-for such it must be admitted-of Newark, N. J. Made in U. S. A. mixing drinks was learned by me, in San Francisco, and, since then, I have had-forty years' experience. Leaving California, in 1868, I opened, in Chicago, what was generally recognized to be the largest and finest establishment of the kind in this country. But the conflagration of 1871 caused me a loss of $100,000 and, financially ruined, I was compelled to start life anew. -

Daytona 500 Audience History ______17

Table of Contents Media Information ____________________________________________________2 Photography _________________________________________________________3 Production Staff ______________________________________________________4 Production Details __________________________________________________5 - 6 Valentine’s Day Daytona 500 Tale of the Tape _____________________________ 7 FOXSports.com at Daytona_____________________________________________ 8 NASCAR ON FOX Social Media _________________________________________ 9 Fox Sports Radio at Daytona _______________________________________10 – 11 FOX Sports Supports: Ronald McDonald House ___________________________12 NASCAR on FOX: 10th Season & Schedule ____________________________ 13-14 Daytona 500 & Sprint Cup Audience Facts____________________________ 15 - 16 Daytona 500 Audience History _________________________________________17 Broadcaster Biographies ___________________________________________18-27 MEDIA INFORMATION This guide has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of the Daytona 500 on FOX and is accurate as of Feb. 8, 2010. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information, photographs and facilitate interview requests. NASCAR on FOX photography, featuring Darrell Waltrip, Larry McReynolds, Mike Joy, Jeff Hammond, Chris Myers, Dick Berggren, Steve Byrnes, Krista Voda and Matt Yocum, is available on FOXFlash.com. Releases on FOX Sports’ NASCAR programming are available on www.msn.foxsports.com