Staffing J. S. Bach's St. Matthew Passion Then And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liturgical Drama in Bach's St. Matthew Passion

Uri Golomb Liturgical drama in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion Bach’s two surviving Passions are often cited as evidence that he was perfectly capable of producing operatic masterpieces, had he chosen to devote his creative powers to this genre. This view clashes with the notion that church music ought to be calm and measured; indeed, Bach’s contract as Cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig stipulated: In order to preserve the good order in the churches, [he would] so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion. (New Bach Reader, p. 105) One could argue, however, that Bach was never entirely faithful to this pledge, and that in the St. Matthew Passion he came close to violating it entirely. This article explores the fusion of the liturgical and the dramatic in the St. Matthew Passion, viewing the work as the combination of two dramas: the story of Christ’s final hours, and the Christian believer’s response to this story. This is not, of course, the only viable approach to this masterpiece. The St. Matthew Passion is a complex, heterogeneous work, rich in musical and expressive detail yet also displaying an impressive unity across its vast dimensions. This article does not pretend to explore all the work’s aspects; it only provides an overview of one of its distinctive features. 1. The St. Matthew Passion and the Passion genre The Passion is a musical setting of the story of Christ’s arrest, trial and crucifixion, intended as an elaboration of the Gospel reading in the Easter liturgy. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION During Lent , Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach performed It is difficult to explain why Bach chose to borrow other his first setting of the Passion according to St. John. Had composers’ music rather than always write his own. After he continued the rotation from Georg Philipp Telemann’s performing his first Passion in , a work based in part time, Bach’s first Passion would have been a setting based and almost on the scale of his father’s St. Matthew Passion, on St. John’s Gospel. In Lent , before Bach arrived in BWV , C. P. E. Bach must have become discouraged or Hamburg, Georg Michael Telemann presented his grand- disillusioned with the Hamburg church authorities. Per- father’s St. Luke Passion of . It is not clear why Bach haps one of the pastors told him this work was too long decided to present a St. Matthew Passion in , skip- and elaborate for the services. In December , Bach ping St. John in the sequence. (e entries in Bach’s estate wrote a letter in which he said: “Hamburg is no place for catalogue indicate that he began assembling his Passions a fine musician to stay. (ere is no taste here. Mostly in the year preceding the season of Lent, so that the St. queer stuff and no pleasure in the noble simplicity.” As John Passion is dated –. While the title page of the early as January Bach mentioned that a pair of the libretto to Telemann’s St. John Passion of states “ein- church elders “said politely but pointedly (it was their gerichtet von G. -

Johann Sebastian Bach's St. John Passion from 1725: a Liturgical Interpretation

Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. John Passion from 1725: A Liturgical Interpretation MARKUS RATHEY When we listen to Johann Sebastian Bach’s vocal works today, we do this most of the time in a concert. Bach’s passions and his B minor Mass, his cantatas and songs are an integral part of our canon of concert music. Nothing can be said against this practice. The passions and the Mass have been a part of the Western concert repertoire since the 1830s, and there may not have been a “Bach Revival” in the nineteenth century (and no editions of Bach’s works for that matter) without Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s concert performance of the St. Matthew Passion in the Berlin Singakademie in 1829.1 However, the original sitz im leben of both large-scaled works like his passions, and his smaller cantatas, is the liturgy. Most of his vocal works were composed for use during services in the churches of Leipzig. The pieces unfold their meaning in the context of the liturgy. They engage in a complex intertextual relationship with the liturgical texts that frame them, and with the musical (and theological) practices of the liturgical year of which they are a part. The following essay will outline the liturgical context of the second version of the St. John Passion (BWV 245a) Bach performed on Good Friday 1725 in Leipzig. The piece is a revision of the familiar version of the passion Bach had composed the previous year. The 1725 version of the passion was performed by the Yale Schola Cantorum in 2006, and was accompanied by several lectures I gave in New Haven and New York City. -

The Crucifixion: Stainer's Invention of the Anglican Passion

The Crucifixion: Stainer’s Invention of the Anglican Passion and Its Subsequent Influence on Descendent Works by Maunder, Somervell, Wood, and Thiman Matthew Hoch Abstract The Anglican Passion is a largely forgotten genre that flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Modeled distinctly after the Lutheran Passion— particularly in its use of congregational hymns that punctuate and comment upon the drama—Anglican Passions also owe much to the rise of hymnody and small parish music-making in England during the latter part of the nineteenth century. John Stainer’s The Crucifixion (1887) is a quintessential example of the genre and the Anglican Passion that is most often performed and recorded. This article traces the origins of the genre and explores lesser-known early twentieth-century Anglican Passions that are direct descendants of Stainer’s work. Four works in particular will be reviewed within this historical context: John Henry Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary (1904), Arthur Somervell’s The Passion of Christ (1914), Charles Wood’s The Passion of Our Lord according to St Mark (1920), and Eric Thiman’s The Last Supper (1930). Examining these works in a sequential order reveals a distinct evolution and decline of the genre over the course of these decades, with Wood’s masterpiece standing as the towering achievement of the Anglican Passion genre in the immediate aftermath of World War I. The article concludes with a call for reappraisal of these underperformed works and their potential use in modern liturgical worship. A Brief History of the Passion Genre from the sung in plainchant, and this practice continued Medieval Era to the Eighteenth Century through the late medieval and early Renaissance eras. -

Editorial Guidelines

CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH he omplete orks Editorial Guidelines The Packard Humanities Institute Cambridge, Massachusetts 2019 Editorial Board Robert D. Levin, Chair Darrell M. Berg, General Editor, Series I Ulrich Leisinger, General Editor, Series IV, V, VI Peter Wollny, General Editor, Series II, III, VII Walter B. Hewlett John B. Howard David W. Packard Uwe Wolf Christoph Wolff † Christopher Hogwood, chair 1999–2014 Editorial Office Paul Corneilson, Managing Editor [email protected] Laura Buch, Editor [email protected] Jason B. Grant, Editor [email protected] M a rk W. K n o l l , Editor [email protected] Lisa DeSiro, Production and Editorial Assistant [email protected] Ruth B. Libbey, Administrator and Editorial Assistant [email protected] 11a Mt. Auburn Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Phone: (617) 876-1310 Fax: (617) 876-0074 Website: www.cpebach.org Updated 2019 Contents Introduction to and Organization of the Edition. 1 A. Prefatory Material. 5 Title Pages . 5 Part Titles . 5 Table of Contents . 5 Order of Pieces . 6 Alternate Versions . 7 Abbreviations . 7 General Preface . 8 Preface to Genres . 8 Introduction . 8 Tables . 8 Facsimile Plates and Illustrations . 9 Captions . 9 Original Dedications and Prefaces . 9 Texts of Vocal Works . 9 B. Style and Terminology in Prose . 10 Titles of Works . 10 Movement Designations . 11 Thematic Catalogues. 11 Geographical Names . 12 Library Names and RISM Sigla . 12 Name Authority. 12 Categories of Works . 13 Varieties of Works . 13 Principal and Secondary Churches of Hamburg . 14 Liturgical Calendar . 14 Keys . 15 Pitch Names and Music Symbols . 15 Dynamics and Terms. 16 Meters and Tempos . -

Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from JS Bach's

Messiahs and Pariahs: Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) to David Lang’s the little match girl passion (2007) Johann Jacob Van Niekerk A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Giselle Wyers, Chair Geoffrey Boers Shannon Dudley Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2014 Johann Jacob Van Niekerk University of Washington Abstract Messiahs and Pariahs: Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) to David Lang’s the little match girl passion (2007) Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Giselle Wyers Associate Professor of Choral Music and Voice The themes of suffering and social conscience permeate the history of the sung passion genre: composers have strived for centuries to depict Christ’s suffering and the injustice of his final days. During the past eighty years, the definition of the genre has expanded to include secular protagonists, veiled and not-so-veiled socio- political commentary and increased discussion of suffering and social conscience as socially relevant themes. This dissertation primarily investigates David Lang’s Pulitzer award winning the little match girl passion, premiered in 2007. David Lang’s setting of Danish author and poet Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Match Girl” interspersed with text from the chorales of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) has since been performed by several ensembles in the United States and abroad, where it has evoked emotionally visceral reactions from audiences and critics alike. -

Background to the Brockespassion Writing a Passion Oratorio Was Not Without Its Dangers in Early Eighteenth-Century Hamburg

Background to the Brockespassion Writing a Passion oratorio was not without its dangers in early eighteenth-century Hamburg. While oratorio Passions—musical works that set the Gospel text with added arias and choruses—were common, Passion oratorios were controversial. The main theological difficulty for conservative Lutherans in Hamburg was that all the characters in a Passion oratorio received newly written verses, even the Evangelist! In fact, it might seem strange for audiences today who have grown up with Bach’s Passions to hear that the Evangelist in Brockes’s text also “speaks” in rhyme. The poetic Passion oratorio trend began in Hamburg in 1704, with the performance of Reinhard Keiser’s setting of Der blutige und sterbende Jesus, on a text by galant poet Christian Friedrich Hunold (known by his Arcadian name of Menantes). Hunold’s at times graphic poetry, celebrating the pain and suffering of Jesus, was highly influenced by contemporary trends toward a bodily understanding of spiritual matters (a feature of Pietism). It also featured something never before seen in a sacred German work: recitatives and arias, which looked (and sounded) far too much like opera for the religious powers of Hamburg. This suspiciously Italian—and therefore Catholic—feature caused outrage, as did the fact that the Passion oratorio was performed in a church attached to the poorhouse of the city (Zuchthauskirche) by singers famous from the Gäsemarkt Oper. How dare Hunold and Keiser give such a secular work a quasi-sacred performance, with opera singers? Even worse, according to a complaint filed in 1705 requesting legal action to prevent further performances of the oratorio, was the text itself: Hunold claimed in the preface of the published libretto that he represents the suffering of Christ even more emphatically than the Holy Evangelist, and even offensively “compares the tears of Peter to baptismal water.” The debate grew more fiery with subsequent attempts at poetic Passions in Hamburg by the composer and organist Georg Bronner, who advertised new works in 1705 and 1710. -

Download Program Book

American Harp Society 2009 8TH SUMMER IN S T I TUTE 1 8 T H N AT I ONAL COMPET I T I ON A Revival of the Early Masters June 28 - July 2 Westminster Brigham Young College University Salt Lake City Provo UTAH American Harp Society 2009 8TH SUMMER IN S T I TUTE 1 8 T H N AT I ONAL COMPET I T I ON A Revival of the Early Masters EXPANDING TH E H A R P ’ S Re P E RTOIR E Lucy Scandrett AHS President Jan Bishop Conference Coordinator ShruDeLi Ownbey, David Day, Anamae Anderson Institute Coordinators June 28 - July 2 Westminster Brigham Young College University Salt Lake City Provo 1250 East 1700 South Harold B. Lee Library Salt Lake City, Utah 84105 Provo, Utah 84602 Acknowledgments We acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for the generous donation of their time, effort, and resources. Lyon & Healy Harps The welcome reception, competition harps, Lyon & Healy Awards, and technician Jason Azem Salvi Harps Competition harps Local AHS Chapter Refreshments for the Board of Directors, Executive Committee, competitors, and AHS Competition judges; flowers Lyon & Healy West Institute logo design, competition support, time Westminster College Jeff Brown Brigham Young University Website, all printed materials and graphics, recording events, ice cream bar and special events day, International Harp Archives expertise, program designer Lindsay Weaver Vanderbilt Music Company Sponsoring Sarah Bullen’s participation Anderson Insurance Two $1,000 scholarships Cherie Campbell Food coordinator Julie Keyes Volunteer coordinator Toni MacKay Registration -

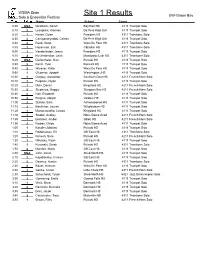

Site 1 Results

WSMA State Site 1 Results UW-Green Bay Solo & Ensemble Festival Name School Event 8:00DNA Mcallister, Sarah Bay Port HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 8:102 Lecaptain, Riannon De Pere High Sch 4111 Trumpet Solo 8:201 Kesler, Dylan Freedom HS 4311 Trombone Solo 8:302 Corriganreynolds, Cainen De Pere High Sch 4111 Trumpet Solo 8:402 Reeb, Noah West De Pere HS 4311 Trombone Solo 8:501 Hoyerman, Eric Gibraltar HS 4311 Trombone Solo 9:001 Vanderlinden, Jenna Freedom HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:102 Kuchenbecker, Leah Manitowoc Luth HS 4311 Trombone Solo 9:20DNA Diefenthaler, Nick Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:302 Bonin, Tyler Roncalli HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:402 Wiesner, Katie West De Pere HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:501 O'connor, Joseph Washington JHS 4111 Trumpet Solo 10:001 Quigley, Alexander Southern Door HS 4211 French Horn Solo 10:101 Fulgione, Dylan Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 10:201 Maki, Daniel Kingsford HS 4211 French Horn Solo 10:302 Stephens, Maggie Sturgeon Bay HS 4211 French Horn Solo 10:402 Hall, Elizabeth Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 10:502 Reigles, Abigail Valders HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:00 2 Stanko, Sam Ashwaubenon HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:10 2 Boettcher, Lauren Wrightstown HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:20 1 Munoz-ozzello, Luiasa Kingsford HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:30 1 Sladek, Audrey Notre Dame Acad 4211 French Horn Solo 11:40 1 Brehmer, Amber Gillett HS 4211 French Horn Solo 11:50 2 Forbes, Chloe Notre Dame Acad 4111 Trumpet Solo 1:001 Kandler, Matheu Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 1:101 Rodeheaver, Eli GB East HS 4311 Trombone Solo 1:201 Kunesh, Sara Pulaski -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s Passion according to St. Maria, was asked by the church authorities in a question- John, H 793 (BR-CPEB D 7.), performed during Lent naire about the sources of the poetry in her late husband’s 1780, was his twelfth Passion and his third setting of John’s music. Question 9 and her answer read: Passion narrative. His estate catalogue (NV 1790, p. 60) [Question] 9. Whether or not he had provided the poetry for lists the dates of composition as 1779–80: “Paßions Musik the music and how he did this? nach dem Evangelisten Johannes. H. 1779 und 1780. Mit [Answer] 9. He received some from good friends, and some Hörnern, Hoboen und Fagotts.” Four years earlier, in 177, were taken from printed books. For installation cantatas the Bach had used the St. John Passion by Gottfried August poet, as far as I know, was sometimes paid by the respective Homilius, HoWV I., for much of the biblical narra- church or the pastor; but this was not always the case. In tive and two of the chorales, but in his last three settings these instances the text was often submitted in writing. In of the St. John Passion (1780, 178, and 1788), Bach re- short, there is no set procedure in this respect.1 turned to Georg Philipp Telemann’s 17 St. John Passion, TVWV 5:30, which he had used as the basis for his first Naturally, some of the choruses can be traced to Psalms or setting of 177. But Bach rarely reused any of the arias, du- other biblical texts, and in his later years Bach also drew ets, or choruses in his Passions, and so the overall impres- more frequently on his songs as the basis for both arias sion is that each of his twenty-one Passions is a separate and choruses. -

Chamber Music Festival

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY Charles A. Sink, President Gail W. Rector, Executive Director Lester McCoy, Conductor Third Concert 1957-1958 Complete Series 3229 Eighteenth Annual Chamber Music Festival BUDAPEST STRING QUARTET JOSEPH ROISMAN, First Violin BORIS KROYT, Viola ALEXANDER SCHNEIDER, Second Violin MISCHA SCHNEIDER, Violoncello ROBERT COURTE, Guest Viola SUNDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 23, 1958, AT 2 :30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM String Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 18, No.6 BEETHOVEN Allegro con brio Adagio ma non troppo Scherzo La MaJinconia; adagio; allegretto quasi allegro String Quartet, Op. 22, No.3 HINDEMITH Very slow quarters Fast eighths-very energetic Quiet quarters Moderately fast quarters Rondo INTERMISSION String Quintet in E-flat major, K. 614 MOZART Allegro eli molto Andante Menuetto: allegretto Allegro Columbia Records A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS MAY FESTIVAL MAY I, 2, 3, 4, 1958 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA AT ALL CONCERTS THURSDAY, MAY 1, 8:30 P.M. LILY PONS, Coloratura Soprano of the "Met" (songs and operatic arias). "Credendum" (Schuman); Symphony in D minor (Franck). EUGENE ORMANDY, <:onductor. FRIDAY, MAY 2, 8:30 P.M. "Samson and Delilah"-opera in concert form, with UNIVERSITY CHORAL UNION; CLARAMAE TURNER, Contralto; BRIAN SULLIVAN, Tenor; MARTIAL SINGHER, Baritone; and YI·KWEI SZE, Bass. THOR JOHNSON, Conductor. SATURDAY, MAY 3, 2:30 P.M. Program of Hungarian music. GYORGY SANDOR, Pianist, in Bartok Concerto No.2; Suite in F-sharp minor (Dohnanyi); Rakoczy March (Liszt); and Dances from "Galanta" (Kodaly). WILLIAM SMITH, Con ductor. FESTIVAL YOUTH CHORUS, Hungarian Folk Songs. MARGUERITE HOOD, Conductor. -

4. Passion in the Work of Johann Sebastian Bach

DOI: 10.1515/rae-2016-0004 Review of Artistic Education no. 11-12 2016 30-41 4. PASSION IN THE WORK OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Karol Medňanský17 Abstract: Passions are exceptionally important in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach. His passion compositions are based particularly on Luther´s reformation, chiefly on developmental tendency which is based on the works of Johann Walter, Hans Leo Hassler and Michael Praetorius. The most significant forerunner of J. S. Bach was Heinrich Schütz. J. S. Bach´s textual aspect is aimed at the model of passion oratorio the main representative of which was a librettist Heinrich Brockes who worked in Hamburg. The interesting fact is that before the arrival of J. S. Bach, in 1723, there was no long tradition of passions in Leipzig. They were performed there in 1721 for the first time. J. S. Bach is demonstrably the author of the two passions: St Matthew Passion BWV 244 and St John Passion BWV 245. The authorship of Johann Sebastian Bach in St. Lukas Passion BWV 246 is strongly called into question and from St Mark Passion BWV 24 only the text was preserved. Key words: passion, reformation, passion oratorio, heritage, tradition 1. Introduction Passions are of an extremely important significance in composer´s heritage by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750). Their importance lies not only in the number of songs, but in their exceptional artistic quality which appeals to the contemporary audience. Their importance lies in the deep philosophical message that the author passes to his audience by means of his music and that is perceived by a wide audience, from the religious and secular minded people.