OSU Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Falsetto Head Voice Tips to Develop Head Voice

Volume 1 Issue 27 September 04, 2012 Mike Blackwood, Bill Wiard, Editors CALENDAR Current Songs (Not necessarily “new”) Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight Spiritual Medley Home on the Range You Raise Me Up Just in Time Question: What’s the difference between head voice and falsetto? (Contunued) Answer: Falsetto Notice the word "falsetto" contains the word "false!" That's exactly what it is - a false impression of the female voice. This occurs when a man who is naturally a baritone or bass attempts to imitate a female's voice. The sound is usually higher pitched than the singer's normal singing voice. The falsetto tone produced has a head voice type quality, but is not head voice. Falsetto is the lightest form of vocal production that the human voice can make. It has limited strength, tones, and dynamics. Oftentimes when singing falsetto, your voice may break, jump, or have an airy sound because the vocal cords are not completely closed. Head Voice Head voice is singing in which the upper range of the voice is used. It's a natural high pitch that flows evenly and completely. It's called head voice or "head register" because the singer actually feels the vibrations of the sung notes in their head. When singing in head voice, the vocal cords are closed and the voice tone is pure. The singer is able to choose any dynamic level he wants while singing. Unlike falsetto, head voice gives a connected sound and creates a smoother harmony. Tips to Develop Head Voice If you want to have a smooth tone and develop a head voice singing talent, you can practice closing the gap with breathing techniques on every note. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Voice Dysphoria and the Transgender and Genderqueer Singer

What the Fach? Voice Dysphoria and the Transgender and Genderqueer Singer Loraine Sims, DMA, Associate Professor, Edith Killgore Kirkpatrick Professor of Voice, LSU 2018 NATS National Conference Las Vegas Introduction One size does not fit all! Trans Singers are individuals. There are several options for the singing voice. Trans woman (AMAB, MtF, M2F, or trans feminine) may prefer she/her/hers o May sing with baritone or tenor voice (with or without voice dysphoria) o May sing head voice and label as soprano or mezzo Trans man (AFAB, FtM, F2M, or trans masculine) may prefer he/him/his o No Testosterone – Probably sings mezzo soprano or soprano (with or without voice dysphoria) o After Testosterone – May sing tenor or baritone or countertenor Third Gender or Gender Fluid (Non-binary or Genderqueer) – prefers non-binary pronouns they/them/their or something else (You must ask!) o May sing with any voice type (with or without voice dysphoria) Creating a Gender Neutral Learning Environment Gender and sex are not synonymous terms. Cisgender means that your assigned sex at birth is in agreement with your internal feeling about your own gender. Transgender means that there is disagreement between the sex you were assigned at birth and your internal gender identity. There is also a difference between your gender identity and your gender expression. Many other terms fall under the trans umbrella: Non-binary, gender fluid, genderqueer, and agender, etc. Remember that pronouns matter. Never assume. The best way to know what pronouns someone prefers for themselves is to ask. In addition to she/her/hers and he/him/his, it is perfectly acceptable to use they/them/their for a single individual if that is what they prefer. -

VB3 / A/ O,(S0-02

/VB3 / A/ O,(s0-02 A SURVEY OF THE RESEARCH LITERATURE ON THE FEMALE HIGH VOICE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Roberta M. Stephen, B. Mus., A. Mus., A.R.C.T. Denton, Texas December, 1988 Stephen, Roberta M., Survey of the Research Literature on the Female High Voice. Master of Arts (Music), December, 1988, 161 pp., 11 tables, 13 illustrations, 1 appendix, bibliography, partially annotated, 136 titles. The location of the available research literature and its relationship to the pedagogy of the female high voice is the subject of this thesis. The nature and pedagogy of the female high voice are described in the first four chapters. The next two chapters discuss maintenance of the voice in conventional and experimental repertoire. Chapter seven is a summary of all the pedagogy. The last chapter is a comparison of the nature and the pedagogy of the female high voice with recommended areas for further research. For instance, more information is needed to understand the acoustic factors of vibrato, singer's formant, and high energy levels in the female high voice. PREFACE The purpose of this thesis is to collect research about the female high voice and to assemble the pedagogy. The science and the pedagogy will be compared to show how the two subjects conform, where there is controversy, and where more research is needed. Information about the female high voice is scattered in various periodicals and books; it is not easily found. -

Vocalist (Singer/Actor)

Vocalist (Singer/Actor) Practitioner 1. Timbre--the perceived sound quality of a musical note or tone that distinguishes different types of sounds from one another 2. Head Voice--a part of the vocal range in which sung notes cause the singer to perceive a vibratory sensation in his or her head 3. Chest Voice-- a part of the vocal range in which sung notes cause the singer to perceive a vibratory sensation in his or her chest 4. Middle Voice-- a part of the vocal range which exists between the head voice and chest voice in a female vocalist 5. Falseto Voice--a part of the vocal range the exist above the head voice in a male vocalist 6. Tessitura—the most musically acceptable and comfortable vocal range for a given singer 7. Modal Voice--the vocal register used most frequently in speech and singing; also known as the resonant mode of the vocal cords, it is the optimal combination of airflow and glottal tension that yields maximum vibration 8. Passaggio--the term used in classical singing to describe the transition between vocal registers (i.e. head voice, chest voice, etc.) 9. Belting—a specific technique of singing by which a singer brings his or her chest register above its natural break point at a loud volume; often described and felt as supported and sustained yelling 10. Melisma—a passage of multiple notes sung to one syllable of text 11. Riffs and Runs –melodic notes added by the singer to enhance the expression and emotional intensity of a song; a form of vocal embellishments during singing 12. -

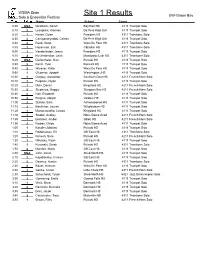

Site 1 Results

WSMA State Site 1 Results UW-Green Bay Solo & Ensemble Festival Name School Event 8:00DNA Mcallister, Sarah Bay Port HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 8:102 Lecaptain, Riannon De Pere High Sch 4111 Trumpet Solo 8:201 Kesler, Dylan Freedom HS 4311 Trombone Solo 8:302 Corriganreynolds, Cainen De Pere High Sch 4111 Trumpet Solo 8:402 Reeb, Noah West De Pere HS 4311 Trombone Solo 8:501 Hoyerman, Eric Gibraltar HS 4311 Trombone Solo 9:001 Vanderlinden, Jenna Freedom HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:102 Kuchenbecker, Leah Manitowoc Luth HS 4311 Trombone Solo 9:20DNA Diefenthaler, Nick Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:302 Bonin, Tyler Roncalli HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:402 Wiesner, Katie West De Pere HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 9:501 O'connor, Joseph Washington JHS 4111 Trumpet Solo 10:001 Quigley, Alexander Southern Door HS 4211 French Horn Solo 10:101 Fulgione, Dylan Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 10:201 Maki, Daniel Kingsford HS 4211 French Horn Solo 10:302 Stephens, Maggie Sturgeon Bay HS 4211 French Horn Solo 10:402 Hall, Elizabeth Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 10:502 Reigles, Abigail Valders HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:00 2 Stanko, Sam Ashwaubenon HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:10 2 Boettcher, Lauren Wrightstown HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:20 1 Munoz-ozzello, Luiasa Kingsford HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 11:30 1 Sladek, Audrey Notre Dame Acad 4211 French Horn Solo 11:40 1 Brehmer, Amber Gillett HS 4211 French Horn Solo 11:50 2 Forbes, Chloe Notre Dame Acad 4111 Trumpet Solo 1:001 Kandler, Matheu Pulaski HS 4111 Trumpet Solo 1:101 Rodeheaver, Eli GB East HS 4311 Trombone Solo 1:201 Kunesh, Sara Pulaski -

Composing for Classical Voice Voice Types/Fach System

Composing for Classical Voice Alexandra Smither A healthy relationship between composer and singer is essential for the creation of new song. Like all good relationships, communication is key. Through this brief talk, I hope to give you some tools, some language you can use as common ground when working together. Remember, we are all individuals with insecurities and vulnerabilities and our art made together should lean on strengths. Being in the room with someone means they are making themselves available to you: this goes both ways, so do what you can to elevate them in the way that they see fit. Composers, remember that to be a singer is to be an athlete. If we are protective of our voices, it’s because we are only given one and it is very delicate. Additionally, the opera world is not kind. Many singers are constantly dealing with rejection and commentary, not just on how they sound, but on how they look and who they are. Remember this, be compassionate, choose your words wisely and kindly. Your singer will appreciate it and will sing all the better for it. Singers, take the time to think about your voice and singing. What do you love to sing? What sounds do you like, even outside singing? How does your voice work? Share this information joyfully and without shame - the music being written will reflect it more the more you talk about it. Be willing to try things in ways that are healthy and sustainable for your body. Embrace your individual identity as singer, person, and artist. -

THE MESSA DI VOCE and ITS EFFECTIVENESS AS a TRAINING EXERCISE for the YOUNG SINGER D. M. A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfi

THE MESSA DI VOCE AND ITS EFFECTIVENESS AS A TRAINING EXERCISE FOR THE YOUNG SINGER D. M. A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Diane M. Pulte, B.M., M.M. *** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Karen Peeler Approved by Dr. C. Patrick Woliver ______________ Adviser Dr. Michael Trudeau School of Music ABSTRACT The Messa di voce and Its Effectiveness as a Training Device for the Young Singer This document is a study of the traditional Messa di voce exercise (“placing of the voice”) and it’s effectiveness as a teaching tool for the young singer. Since the advent of Baroque music the Messa di voce has not only been used as a dynamic embellishment in performance practice, but also as a central vocal teaching exercise. It gained special prominence during the 19th and early 20th century as part of the so-called Bel Canto technique of singing. The exercise demonstrates a delicate balance between changing sub-glottic aerodynamic pressures and fundamental frequency, while consistently producing a voice of optimal singing quality. The Messa di voce consists of the controlled increase and subsequent decrease in intensity of tone sustained on a single pitch during one breath. An early definition of the Messa di voce can be found in Instruction Of Mr. Tenducci To His Scholars by Guisto Tenducci (1785): To sing a messa di voce: swelling the voice, begin pianissimo and increase gradually to forte, in the first part of the time: and so diminish gradually to the end of each note, if possible. -

Chamber Music Festival

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY Charles A. Sink, President Gail W. Rector, Executive Director Lester McCoy, Conductor Third Concert 1957-1958 Complete Series 3229 Eighteenth Annual Chamber Music Festival BUDAPEST STRING QUARTET JOSEPH ROISMAN, First Violin BORIS KROYT, Viola ALEXANDER SCHNEIDER, Second Violin MISCHA SCHNEIDER, Violoncello ROBERT COURTE, Guest Viola SUNDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 23, 1958, AT 2 :30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM String Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 18, No.6 BEETHOVEN Allegro con brio Adagio ma non troppo Scherzo La MaJinconia; adagio; allegretto quasi allegro String Quartet, Op. 22, No.3 HINDEMITH Very slow quarters Fast eighths-very energetic Quiet quarters Moderately fast quarters Rondo INTERMISSION String Quintet in E-flat major, K. 614 MOZART Allegro eli molto Andante Menuetto: allegretto Allegro Columbia Records A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS MAY FESTIVAL MAY I, 2, 3, 4, 1958 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA AT ALL CONCERTS THURSDAY, MAY 1, 8:30 P.M. LILY PONS, Coloratura Soprano of the "Met" (songs and operatic arias). "Credendum" (Schuman); Symphony in D minor (Franck). EUGENE ORMANDY, <:onductor. FRIDAY, MAY 2, 8:30 P.M. "Samson and Delilah"-opera in concert form, with UNIVERSITY CHORAL UNION; CLARAMAE TURNER, Contralto; BRIAN SULLIVAN, Tenor; MARTIAL SINGHER, Baritone; and YI·KWEI SZE, Bass. THOR JOHNSON, Conductor. SATURDAY, MAY 3, 2:30 P.M. Program of Hungarian music. GYORGY SANDOR, Pianist, in Bartok Concerto No.2; Suite in F-sharp minor (Dohnanyi); Rakoczy March (Liszt); and Dances from "Galanta" (Kodaly). WILLIAM SMITH, Con ductor. FESTIVAL YOUTH CHORUS, Hungarian Folk Songs. MARGUERITE HOOD, Conductor. -

Low Male Voice Repertoire in Contemporary Musical Theatre: a Studio and Performance Guide of Selected Songs 1996-2020

LOW MALE VOICE REPERTOIRE IN CONTEMPORARY MUSICAL THEATRE: A STUDIO AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE OF SELECTED SONGS 1996-2020 by Jeremy C. Gussin Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Ray Fellman, Research Director __________________________________________ Brian Gill, Chair __________________________________________ Jane Dutton __________________________________________ Peter Volpe December 10, 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 Jeremy Gussin iii Preface This project is intended to be a resource document for bass voices and teachers of low male voices at all levels. For the purposes of this document, I will make use of the established term low male voice (LMV) while acknowledging that there is a push for the removal of gender from voice classification in the industry out of respect for our trans, non-binary and gender fluid populations. In addition to analysis and summation of musical concepts and content found within each selection, each repertoire selection will include discussions of style, vocal technique, vocalism, and character in an effort to establish routes towards authenticity in the field of musical theatre over the last twenty five years. The explosion of online streaming and online sheet music resources over the last decade enable analysis involving original cast recordings, specific noteworthy performances, and discussions on transposition as it relates to the honoring of character and capability of an individual singer. My experiences with challenges as a young low voice (waiting for upper notes to develop, struggling with resonance strategies above a D♭4) with significant musicianship prowess left me searching for a musically challenging outlet outside of the Bel Canto aesthetic. -

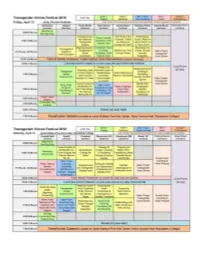

Presenter Biographies

Transgender Voices Festival Schedule: Program Descriptions and Presenter Biographies 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. Registration and snacks available throughout the day (Unity Parish Hall, 1st floor) 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. Quiet Room Available (Unity DeCramer Room, 1st floor) 9:00–9:30 a.m. Welcome and Morning Sing Location: Unity Sanctuary (1st floor) Welcome to the festival! We'll hear from a few organizers, and featured guest Alex Iantaffi will lead us in some whole body wake-up time, then featured guest Eli Conley will lead us in some group singing. Then we'll have a special treat of hearing from a trans quartet from One Voice Mixed Chorus! Friday Breakout Session 1: 9:45-11:00 a.m. Trans and Gender Nonbinary Youth Voices Festival Choir (Part 1) Conducted by featured guest André Heywood (he/him) Piano accompanist Kymani Kahlil (she/her); assisted by Joselyn Fear (she/her) Location: Unity Choir Room (2nd floor) Come sing in a youth choir with other young trans and nonbinary singers, ages 14-20! We'll learn 2-3 pieces together and then perform them for the festival just before lunch on Friday. Singers of ALL levels of experience, ability to read music, previous choral singing, etc. are welcome. Teachers are welcome and encouraged to attend other concurrent sessions geared toward voice and music teachers and choir directors. Creating Choirs that Welcome Transgender Singers with featured guest Erik Peregrine (they/them or he/him) and Jane Ramseyer Miller (she/her) Location: Unity Foote Room (2nd floor) An overview of strategies for creating choirs that affirm transgender and gender non-conforming singers, including topics such as repertoire selection, rehearsal language, basic pedagogy for transitioning voices, performance attire, pronouns, terminology, and allyship.