Transactions Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listings Information for Herefordshire Wildlife Trust's Events in June 2016 Wild Garden Party Wed 1 June 5.30-7.30Pm a Garden

Listings information for Herefordshire Wildlife Trust’s events in June 2016 Wild Garden Party Wed 1 June 5.30-7.30pm A garden tea party to launch Herefordshire Wildlife Trust’s 30 Days Wild campaign. An evening event to celebrate all the wildlife you can find in your garden. Drop in to Lower House Farm for tea and cake and enjoy informal talks from our staff and volunteers about our wildlife garden and orchard. Venue: Herefordshire Wildlife Trust, Lower House Farm, Ledbury Road, Tupsley, Hereford HR1 1UT Cost: Free event No booking required River Lugg Living Landscape talk – part of Leominster Festival Fri 3 June 7.30pm-9.30pm A supper talk by Sophie Cowling, Ecologist and Living Landscape Project officer for Herefordshire Wildlife Trust, on how the Wildlife Trust is working with local landowners in order to benefit wildlife, business and the landscape of the River Lugg. Venue: Pudleston Village Hall, Pudleston, Leominster, Herefordshire, HR6 0RA Cost: £12 Entry is by ticket only Bookings can be made by emailing [email protected] or phone 01568 750303. Hay Meadow walk at Sturts North Nature Reserve Sat 4 June 10am-1pm An opportunity to walk across this flower rich traditionally managed flood plain grassland with reserves officer Jim Light. You will have the opportunity to see specialist species like the Great burnet, Pepper saxifrage, Dyers greenweed, Birds foot trefoil, Greater birdsfoot trefoil, Knapweed, Ragged robin, Lesser spearwort and Meadow sweet. The rougher pasture and hedgerows offer fantastic nesting and feeding habitat for raptors such as Kestrel, Sparrow-hawk, Kite and Buzzard. -

The Destruction of Abinger Church 3 Aug 1944

The Destruction of Abinger Church 3 Aug 1944 St James' Church 1938 The following is, in shortened form, the report read at a meeting of the Church Council on the 19 th August, 1944, and adopted by them. Released by the Censor on the 7 th September , it is now being sent to every home in the Parish, as it is felt that everyone would wish to see it. Our beautiful and well-beloved church, in both inside and outside, were completely which the people of this parish have worshipped demolished, and so was the south door and porch, for over 850 years, was destroyed in a moment a great part of of the north wall including the three some weeks ago by a flying bomb of the enemy. little Norman windows of that side, and the south The bomb fell just when the Rector was leaving his wall up to a point beyond the porch. In the house to take the Holy Communion Service at 8 remains of the south wall are left the easternmost a.m. And, mercifully, no one had arrived at the of the three Norman windows of that side and the Church. It seems to have exploded in the air after three-light 15 th century window (damaged) near hitting the belfry or its spire, or maybe the tall where the pulpit stood. The two eastern-most tie- cypress tree which grew close to the south-west beams of the Nave alone remain (but much corner of the Nave, The lower part of that tree still damaged) to represent the roof. -

Broseley Much Wenlock

Ù Ù Ù NCN 45 Ù NCN 552 M E H Y A L Ù H R C E 4 D B to Chester C to Audlem N R 1 U 5 R L E 0 U T U E W C A S 2 T N 6 H H O O T T C C 3 O T T 5 I W A I Ù A H H S H A W I H 5 L O W T T C 2 E H 9 Y 6 O 7 U H T T 5 4 R Bletchley E B C O A 9 H T H N 4 Market Drayton A A Broughton N T N W I C H Prees A41 Fairoak Ternhill S Edstaston h Croxton r o p A53 s Chipnall Prees h i r Green e U n i o Hawkstone Wollerton n Hawkstone Historic Park C Cheswardine a & Follies n a Marchamley R l Pershall i Bishop’s R i v v e e Wem E r R E r M R Ofey E S o Wistanswick E L L Hodnet T O d Ù 5 T Great Soudley 6 e B 5 0 e r n n Hodnet Hall Hawkstone Park & Gardens Lockleywood Shropshire Union and Follies Stoke Canal Historic woodlands Historic canal. Day and monuments, tea upon Tern Knightonboat hire available Lee room and parking from Norbury Junction 9 Brockhurstwww. A52 on the Shropshire/ hawkstoneparkfollies. Staffordshire border. co.uk A519 B Hodnet Hall A41 6 5 0 6 47 3 Gardens 5 Woodseaves B A49 Booley Hall, gardens, Hinstock Preston restaurant and parking Shebdon Brockhurst www. -

Local Authorities and Other Local Public Bodies Which Hold Government Procurement Cards

Local authorities and other local public bodies which hold Government Procurement Cards Customer Name Aberdeen College Abingdon and Witney College Accrington and Rossendale College Adur District Council Alderman Blaxill School All Saints Junior School Allerdale Borough Council Allesley Primary School Alleyns School Alton College Alverton Community Primary School Amber Valley Borough Council Amherst School Anglia Ruskin University Antrim Borough Council Argyll and Bute Council Ashfield District Council Association of North Eastern Councils Aston Hall Junior and Infant School Aston University Aylesbury Vale District Council Babergh District Council Baddow Hall Infant School Badsley Moor Infant School Banbridge District Council Bangor University Bankfoot Primary School Barmston Village Primary School Barnes Farm Junior School BARNET HOMES Barnsley College Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Barrow in Furness Sixth Form College Barton Court Grammar School Barton Peveril College Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council Basingstoke College of Technology Bassetlaw District Council Bath and North East Somerset Council Beauchamp College Beckmead School Bede College Bedford Academy Bedford College Belfairs High School Belfast City Council Belvoir High School and Community Centre Bexley College Biddenham Upper School Billingborough Primary School Birchfield Educational Trust Birkbeck College Birkenhead Sixth Form College Birkett House School Birmingham City University Bishop Ullathorne Catholic School Bishops Waltham Infant School Bishopsgate School -

Leominster Team Rector Team Profile, April 2021

Leominster Team Rector Team Profile, April 2021 Leominster Priory Choir The Wisdom of Winnie the Pooh: Pudleston’s 2019 Flower Festival 1 Leominster Team Profile Welcome from the Deanery Leadership Team The Diocese of Hereford is one of the most rural in the Church of England, and Leominster Deanery is no exception. We comprise five rural benefices plus the Leominster Team Ministry, stretching as the crow flies nearly 18 miles from the Welsh border across the northern reaches of Herefordshire into Worcestershire and over 20 miles from Leintwardine on the Shropshire border to Pipe-cum-Lyde on the northern outskirts of Hereford. Ours has been a forward-thinking Deanery, leading the way in collaborative ministry, new vocations and fulfilment of parish offer. But it is a time of transition; as well as the appoint- ment of a new rector to the Leominster Team, two new benefices joined us on 1 April 2021. These changes provide an opportunity to work together with the newly formed Deanery Leadership Team, creating a new Mission Action Plan and Deanery Pastoral Scheme, and re-examining the best models for joint ministry across the Leominster Team. The clergy chapter currently meets about ten times a year, as well as meetings which include the Deanery Lay Co-Chair, Deanery Leadership Team, Readers and other licenced lay ministers. Once or twice a year (when pre-Covid arrangements resume) there is a social event to which clergy with PTOs and their spouses/partners are also invited. The Diocese of Hereford operates on a ‘parish offer’ model, and the total offer budgeted by the deanery for 2021 is £363,111. -

CONTENTS Page

CONTENTS Page Contact Points Inside Front Contacts In Neighbouring Authorities 2 Letter from Director of Children’s Services 3 Open Days Evenings for Phase Transfers 2009/2010 4 Herefordshire Choice Advisor Service 5 About High Schools In Herefordshire 6 General Admission Arrangements for High Schools 7 Transfer to High School 9 Allocation of Places in High Schools 13 School Transport up to the age of 16 18 Post 16 Education, Transport and Careers 23 National Curriculum and Assessment Arrangements 27 Charges, School Meals, and Allowances 30 Education Welfare Service and School Uniform 32 Special Education 33 Special Schools, Classes and Centres 37 Transport for Pupils and Students with Special Education Needs 38 Procedures for dealing with parental concerns or complaints about 40 individual schools Map of Herefordshire 42 Appendix 1 - Local code of practice for admissions authorities and schools concerning contacts with parents on pupil admissions, transfers and exclusions Appendix 2 - Co-ordinated secondary admission arrangements Appendix 3 - Information about schools in each district of Herefordshire Appendix 4 - Admission policies of voluntary aided schools, academy and Foundation Appendix 5 - Admission policies for admissions to school Sixth Form Appendix 6 - Quick reference guide to provided schools for parishes in Herefordshire Appendix 7 - Post 16 Transport – Policies Appendix 8 - Data Protection Act – Notice of Fair Processing 1 Apply on line for a place at a Secondary school for September 2009 at www.cs.herefordshire.gov.uk CONTACT -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Healthy Ways for Clergy & Vestries to Work Together

HEALTHY WAYS FOR CLERGY & VESTRIES TO WORK TOGETHER DIOCESE OF NEWARK VESTRY UNIVERSITY 2014 Maintaining Healthy Clergy-Vestry Relationships Vestry University 2014 Why Are We Offering This Workshop? A true story: Both wardens in one of our congregations asked to see me about some “difficulties” they were having with the rector. “The rector doesn’t respect the wardens or the vestry”. “The rector makes decisions without consulting us”. “The rector’s working motto seems to be “‘it’s my way or the highway’ ”. One of the wardens candidly confessed, we don’t communicate, we avoid one another”. And on and on it went for a good ½ hour. After the wardens had recited their list of “Sins the Rector has committed”, I innocently observed: “All that you say may be true, well and good, but my friends, it takes two to tango, and I ‘m not hearing what you are doing proactively to deal with this issue”. And when we dug deeper, we unearthed a congregational culture that had been perennially characterized by non- communication between clergy, wardens and vestry, triangulating as the chosen method of communicating, and an utter lack of respect for one another evidenced in even the simplest conversations. Truth be told, this is by no means an isolated occurrence in our diocese. The Bishop’s Office in the past few years has had to intervene in more than a few instances where there was a total breakdown in the relationship between lay leaders and clergy. Many of these situations, sadly enough could have been avoided had the clergy and the leadership put in place some healthy practices that promoted open, honest, and healthy behaviors among one another. -

About Vestries Our Vestries Owe Much to the Historical Evolution of The

About Vestries Our vestries owe much to the historical evolution of the Episcopal Church in Virginia. Of course, the Church of England was the established church during colonial times, but there was no attempt to help the colonies become self-sufficient. The bishop of the colonies was the Bishop of London, who never came to the New World, and there was no seminary established here, either. Furthermore, C of E clergy had to swear an oath of allegiance to the king. Thus, after America gained its freedom, there were no clergy immediately available. In this vacuum, lay leadership predominated. The church was the driving force behind maintenance of the social order, and the vestries were the driving force behind the church. The Anglicans who came to Virginia were not dissidents but businessmen seeking economic opportunity, and they ended up owning much of the property and means of production in the colony. They had a sense of themselves as caretakers of the community and responsible for its health. This is the root of the emphasis on lay ministry and the responsibility of the laity in Virginia. The national canons establish that each church must have a vestry, but leave it up to each diocese to decide how it is are to be structured and chosen in accordance with diocesan canons and state law. In Virginia, vestries are elected annually by the congregation to a term not to exceed four years. A vestry consists of at least three members, but not more than 12, except for large churches, which may have up to 18. -

SHROPSHIRE WAY SOUTH SECTION About Stage 8: Wilderhope to Ironbridge 12.5 Miles

SHROPSHIRE WAY SOUTH SECTION About Stage 8: Wilderhope to Ironbridge 12.5 miles On reaching a stream turn right and continue beside small lakes to reach Easthope village. From here you can ascend to Wenlock Edge and the Shropshire Way once more. Much Wenlock It is worth allowing time to enjoy this pretty market town with fine timbered buildings, an ancient Guildhall and a Priory, to mention just a few of its attractions. There is a small museum with information on William Penny Brookes Early purple orchids who founded the Wenlock Olympian Society, the forerunner of the modern Olympic Games. Wenlock Edge Leave Much Wenlock walking alongside the The route from Wilderhope goes for about six Priory. miles along Wenlock Edge made famous by A.E Housman and Vaughan Williams. For the first Ironbridge half there is a variant, see below and use an OS The power station that you pass on the steep map. The second half is more interesting with descent into Ironbridge is now redundant and wild flowers including orchids in spring time. becoming a vestige of the industrial past of the Gorge. It may or may not still have four massive Alternative route: cooling towers that have been such a feature of Head North-eastwards from Wilderhope to the landscape in recent years. Pilgrim Cottage. Turn right and continue to SO556936 and take the forest track across After a riverside walk past old lime kilns you will Mogg Forest. (The path by Lutwyche Hall is not enter the town across the famous Ironbridge recommended). There is a hidden hillfort with to reach many tourist attractions including well-defined ramparts for those with time to cafes, shops and museums. -

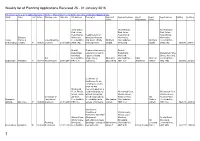

Weekly List of Planning Applications Received 25 to 31 January 2016

Weekly list of Planning Applications Received 25 - 31 January 2016 Direct access to search application page click here https://www.herefordshire.gov.uk/searchplanningapplications Parish Ward Unit Ref no Planning code Valid date Site address Description Applicant Applicant address Agent Agent Agent address Easting Northing name Organisation name 1633 Sinton 1633 Sintons 1633 Sintons End, Acton End, Acton End, Acton Beauchamp, Replacement of Beauchamp, Beauchamp, Bishops Worcester, decayed windows Worcester, Worcester, Acton Frome & Listed Building Herefordshire, and doors. (Partly Mr Ryan Herefordshire, Mr Ryan Herefordshire, Beauchamp Cradley P 160035 Consent 27/01/2016 WR6 5AE Retrospective) Sudall WR6 5AE Sudall WR6 5AE 368690 249113 Bunhill, Proposed two storey Bunhill, Bodenham, extension to rear to Bodenham, Watershed, Wye Hereford, replace existing Hereford, Street, Hereford, Full Herefordshire, single;storey Mr & Mrs Herefordshire, RRA Mr Fred Herefordshire, Bodenham Hampton P 160164 Householder 20/01/2016 HR1 3JY extension. Bloomfield HR1 3JY Architects Hamer HR2 7RB 353350 251258 Certificate of lawfulness for an existing use as the property has Westwood been;occupied as a View, Phocle residential property Westwood View, Westwood View, Green, Ross- without complying Phocle Green, Phocle Green, Certificate of On-Wye, with the;agricultural Ross-on-Wye, Ms Ross-on-Wye, Brampton Lawfulness Herefordshire, tie condition for in Ms Andrea Herefordshire, Andrea Herefordshire, Abbotts Old Gore P 160046 (CLEUD) 21/01/2016 HR9 7TL excess of 10 years. Gilbert HR9 7TZ Gilbert HR9 7TZ 362178 225832 Variation of Condition 2 Wicton Farm, Reference 151676/F Wicton Lane, Wicton Farm, (Proposed Winslow, 5a Old Road, Wicton Lane, agricultural;workers Bromyard, Mr Bromyard, Planning Bromyard, dwelling) - change of Mr Anthony Herefordshire, Leonard Herefordshire, Bredenbury Hampton P 160098 Permission 21/01/2016 Herefordshire roof materials. -

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: with a Catalogue of Artefacts

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: With a catalogue of artefacts By Esme Nadine Hookway A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MRes Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Anglo-Saxon period spanned over 600 years, beginning in the fifth century with migrations into the Roman province of Britannia by peoples’ from the Continent, witnessing the arrival of Scandinavian raiders and settlers from the ninth century and ending with the Norman Conquest of a unified England in 1066. This was a period of immense cultural, political, economic and religious change. The archaeological evidence for this period is however sparse in comparison with the preceding Roman period and the following medieval period. This is particularly apparent in regions of western England, and our understanding of Shropshire, a county with a notable lack of Anglo-Saxon archaeological or historical evidence, remains obscure. This research aims to enhance our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon period in Shropshire by combining multiple sources of evidence, including the growing body of artefacts recorded by the Portable Antiquity Scheme, to produce an over-view of Shropshire during the Anglo-Saxon period.