""The More Things Change ..." : the World Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Most Lasting Impact of the Imperial Rule in the Jalpaiguri District

164 CHAPTER 111 THE BRITISH COLONIAL AUTHORITY AND ITS PENETRATION IN THE CAPITAL MARKET IN THE NORTHERN PART OF BENGAL The most lasting impact of the imperial rule in the Jalpaiguri District especially in the Western Dooars was the commercialisation of agriculture, and this process of commercialisation made an impact not only on the economy of West Bengal but also on society as well. J.A. Milligan during his settlement operations in the Jalpaiguri District in 1906-1916 was not im.pressed about the state of agriculture in the Jalpaiguri region. He ascribed the backward state of agriculture to the primitive mentality of the cultivators and the use of backdated agricultural implements by the cultivators. Despite this allegation he gave a list of cash crops which were grown in the Western Duars. He stated, "In places excellent tobacco is grown, notably in Falakata tehsil and in Patgram; mustard grown a good deal in the Duars; sugarcane in Baikunthapur and Boda to a small extent very little in the Duars". J.F. Grunning explained the reason behind the cultivation of varieties of crops in the region due to variation in rainfall in the Jalpaiguri district. He said "The annual rainfall varies greatly in different parts of the district ranging from 70 inches in Debiganj in the Boda Pargana to 130 inches at Jalpaiguri in the regulation part of the district, while in the Western Duars, close to the hills, it exceeds 200 inches per annum. In these circumstances it is not possible to treat the district as a whole and give one account of agriculture which will apply to all parts of it".^ Due to changes in the global market regarding consumer commodity structure suitable commercialisation at crops appeared to be profitable to colonial economy than continuation of traditional agricultural activities. -

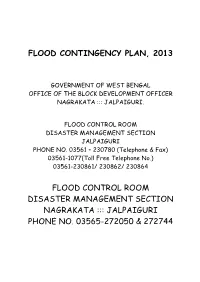

Disaster Management Plan of Nagrakata Block

FLOOD CONTINGENCY PLAN, 2013 GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL OFFICE OF THE BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER NAGRAKATA ::: JALPAIGURI. FLOOD CONTROL ROOM DISASTER MANAGEMENT SECTION JALPAIGURI PHONE NO. 03561 – 230780 (Telephone & Fax) 03561-1077(Toll Free Telephone No.) 03561-230861/ 230862/ 230864 FLOOD CONTROL ROOM DISASTER MANAGEMENT SECTION NAGRAKATA ::: JALPAIGURI PHONE NO. 03565-272050 & 272744 Introduction Block administration in general, and all three tier P.R. bodies in particular are giving the best of their activities to all round development of human habitats including living and material properties. As a part of developmental administrative wing, effort with a view to achieving target of materializing a really developed state of affairs in every sphere of our lives, are always exerted & ideas put forth by all concerned. However, much of our sincere endeavors in this direction are so often battered & hamstrung by sudden visit of ominous calamities and evil disasters. Thus, to combat such ruthless spells & minimize risk hazards and loss of resources, surroundings, our achievements, concrete preparation on Disaster Management is an inevitable part of our curriculum. Such preparedness of ours undoubtedly involves all departments, sectors concerned. Hence, we prepare a realistic Flood Contingency Plan to combat the ruthless damage caused to our flourishing habitats. Accordingly, this time for 2013, an elaborate plan has been worked out with every aspiration to successfully rise above the situation pursuing a planned step forward. BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER NAGRAKATA ::: JALPAIGURI. CONTACT TELEPHONE NUMBERS FOR NAGRAKATA DEVELOPMENT BLOCK. SL. Name of the Office Telephone No. NO. 01. B.D.O, Nagrakata 03565-272050 Savapati, 02. Nagrakata Panchayat 03565-272309 Samity 03. -

SASEC Road Connectivity Investment Program

Resettlement and Indigenous Peoples Plan January 2014 IND: SASEC Road Connectivity Investment Program Changrabandha - Mainaguri - Dhupguri - Birpara - Hasimara – Jaigaon Section of Asian Highway 48 Prepared by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 13 December 2013) Currency unit – Indian rupee (Rs) INR1.00 = $ 0.016075 $1.00 = INR 62.209 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AH – Asian Highway BL&LRO – Block Land and Land Reforms Officer BPL – Below Poverty Line CoI – Corridor of Impact DH – Displaced Household DM – District Magistrate / District Collector DP – Displaced Person EA – Executing Agency FGD – Focus Group Discussion GRC – Grievance Redress Committee GRM – Grievance Redress Mechanism GoWB – Government of West Bengal LA Act – Land Acquisition Act, 1894 L&LRO – Land and Land Reforms Officer The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land LARR – Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 MoRTH – Ministry of Road Transport and Highways NH – National Highway NH Act – National Highways Act, 1956 NGO – Non Governmental Organization NRRP – National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy, 2007 PIU – Project Implementation Unit PMU – Project Management Unit PW(R)D – Public Works (Roads) Department RF – Resettlement Framework RO – Resettlement Officer RP – Resettlement Plan R&R – Resettlement and Rehabilitation RoB – Road over Bridge RoW – Right of Way SASEC – South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation SH – State Highway SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement ST – Scheduled Tribe ST-DHs – Scheduled Tribe Displaced Households WBEA Act – West Bengal Estates Acquisition Act, 1953 WHH – Women Headed Household WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 1 hectare = 2.47 acre 1 kattha = 720 sq.ft 20 kattha = 1 bigha 1 bigha = 0.3306 acre = 1338 sq.m NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars This resettlement framework is a document of the borrower. -

Alipurduar1.Pdf

INDEX SL. SUBJeCt PAGe NO NO 01 FOReWORD 1 02 DIStRICt PROFILe 3 – 7 ACtION PLAN 03 BDO ALIPURDUAR-I 8 – 35 04 BDO ALIPURDUAR-II 36 –80 05 BDO FALAKAtA 81 – 134 06 BDO MADARIHAt-BIRPARA 135 – 197 07 BDO KALCHINI 198 – 218 08 BDO KUMARGRAM 219 – 273 09 ALIPURDUAR MUNICIPALItY 274 –276 10 SP ALIPURDUAR 277 – 288 11 IRRIGAtION DIVISION , ALIPURDUAR 289 – 295 12 CMOH , ALIPURDUAR 296 – 311 13 DIStRICt CONtROLLeR , FOOD & SUPPLIeS , ALIPURDUAR 312 – 319 14 DY. DIReCtOR , ANIMAL ReSOURCeS DeVeLOPMeNt 320 – 325 DePtt. , ALIPURDUAR 15 eXeCUtIVe eNGINeeR , PWD , ALIPURDUAR DIVISION 326 – 331 16 eXeCUtIVe eNGINeeR , NAtIONAL HIGHWAY DIVISION – X , 332 – 333 PWD 17 ASSIStANt eNGINeeR , PHe Dte. , ALIPURDUAR SUB - 334 – 337 DIVISION 18 DePUtY DIReCtOR OF AGRICULtURe ( ADMN) 338 – 342 ALIPURDUAR 19 SDO teLeGRAPH , ALIPURDUAR 343 – 345 20 DIVISIONAL MANAGeR, ALIPURDUAR(D) DIVISION , 346 – 347 WBSeDCL 21 OFFICeR IN CHARGe , ALIPURDUAR FIRe StAtION 348 22 DI OF SCHOOLS 349 – 353 23 CIVIL DeFeNCe DePtt. 354 – 355 FOREWORD Alipurduar district is the 20th and newest district of the state of West Bengal and was made a separate district on 25th June 2014 . The district is diverse in terrain as well as ethnicity . Places like the Buxa Tiger Reserve , Jaldapara National Park , Jayanti Hills , Buxa Fort have always drawn people to this beautiful district . The district also many rivers like Torsha, Holong , Mujnai , Rydak , Kaljani , Sankosh to name a few . The presence of many rivers makes the district a possible victim of floods during the monsoons every year .The year 1993 is notable as it was in this year that the district was ravaged by severe floods . -

3 an EMPIRICAL STUDY ON.Cdr

IJRTBT AN EMPIRICAL STUDY ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF TEA INDUSTRY IN WEST BENGAL Indranil Chatterjee1*, Amit Majumdar2 1Mewar University, Rajasthan, India 2Department of Commerce, Bijoy Krishna Girls College, Howrah, India *Corresponding Author's Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Introduction: Economic Development is the primary issue of any developed/developing countries. Economic growth of any country depends on the slandered of living for its countrymen. It could be measured which may be taken under a framed structure through adoption of updating technologies from agricultural field to industry field. Literature Review: Tea Industry is a second foreign exchange earner in India. More than 50% women workers are employed in tea estates. Being most of the tea gardens are situated in the remote corner of the various States in India, tea industry is always trying to holistic development of their workers as well as local people. Tea industry is an agricultural-based industry which had already recognised by RBI (Reserve Bank of India). Research Methodology: The study has covered two tea estates in West Bengal. Primary Information is collected through interviews by preparing questionnaire. Secondary Information is collected from newspapers, Journals and public domain. Results & Discussion: (i) In Tea industry more than 50% workers are women. (ii) Tea Industry is a second foreign exchange earner in India. (iii) After Railway & Armed Force, tea Industry is the largest employer in India, and (iv) Being tea gardens are situated in the remote corners of the country, tea industry has already taken various steps to up- lift their workers as well as local people. Conclusion: In this paper has been structured to analyse how the tea industry fulfil their task towards their economic development for their workers and looked out to analyse their performance towards their contribution in the society. -

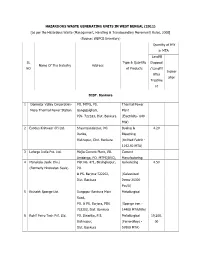

Hazardous Waste Generating Units in West Bengal (2011

HAZARDOUS WASTE GENERATING UNITS IN WEST BENGAL (2011) [as per the Hazardous Waste (Management, Handling & Transboundary Movement) Rules, 2008] (Source: WBPCB Inventory) Quantity of HW in MTA Landfill SL Type & Quantity Disposal Name Of The Industry Address NO of Products / Landfill Inciner After ation Treatme nt DIST. Bankura 1 Damodar Valley Corporation- PO. MTPS, PS. Thermal Power Mejia Thermal Power Station. Gangajalghati, Plant PIN- 722183, Dist. Bankura (Electricity- 840 MW) 2 Exodus Knitwear (P) Ltd. Shyamsundarpur, PO. Dyeing & 4.20 Darika, Bleaching Bishnupur, Dist. Bankura (Knitted Fabric - 1192.92 MTA) 3 Lafarge India Pvt. Ltd. Mejia Cement Plant, Vill. Cement Amdanga, PO. MTPS(DVC), Manufacturing 4 Manaksia (Galv. Div.) PIN.Plot No.722183 471, Birsinghapur, PortlandGalvanizing Cement 4.50 (Formerly Hindustan Seals) PO. - 83330 MTA) & PS. Barjora-722202, (Galvanized Dist. Bankura Items-36000 Pcs/A) 5 Rishabh Sponge Ltd. Durgapur Bankura Main Metallurgical Road, PO. & PS. Barjora, PIN. (Sponge iron - 722202, Dist. Bankura 14400 MTA/Kiln) 6 Rohit Ferro Tech Pvt. Ltd. PO. Dwarika, P.S. Metallurgical 19,200. Bishnupur, (Ferro-alloys - 00 Dist. Bankura 57600 MTA) 7 Rohit Ferro Tech Pvt. Ltd. PO. Dwarika, P.S. Metallurgical 12,144. (Unit-II) Bishnupur, (Ferro-alloys - 00 Dist. Bankura, PIN. 722122 18000 MTA) Metallurgical 14,628. (Ferro-alloys - 00 12192MTA) DIST. Burdwan 1 Alloy Steel Plant Durgapur, Dist. Burdwan Metallurgical (Alloy Steel- 208149 MTA) 2 Alstom Projects Durgapur, Dist. Burdwan Engineering 0.20 India Ltd. (Steel (formerly Alstom Fabrication - Power Boilers Ltd.) 1500 MTA) 3 Associated Trade G. T. Road, PO. Ningha, PS. Oxyzen gas Link Jamuria, Asansol, PIN. filling & storing 713370 centre Dist. -

SASEC Road Connectivity Investment Program – Tranche 1

Social Safeguard Due Diligence Report July 2017 IND: SASEC Road Connectivity Investment Program – Tranche 1 Prepared by Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of May 2017) Currency unit – Indian Rupee (Rs) INR1.00 = $ 0.01555 $1.00 = INR 64.32 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BSR – Basic Schedule of Rates DC – District Collector DH – Displaced household DP – Displaced person EA – Executing Agency GRC – Grievance Redressal Committee IA – Implementing Agency IAY – Indira Awaas Yojana LA – Land acquisition LAA – Land Acquisition Act, 1894 L&LRO – Land and Land Revenue Office RFCT in LARR – The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Act - 2013 Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 LVC – Land Valuation Committee MORTH – Ministry of Road Transport and Highways NGO – Nongovernment organization NHA – National Highways Act, 1956 NRRP – National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy, 2007 PD – Project Director PIU – Project implementation unit MPWD – Manipur Public Works Department WBPWD – West Bengal Public Works (Roads) Department R&R – Resettlement and rehabilitation RF – Resettlement framework RO – Resettlement Officer ROW – Right-of-way RP – Resettlement plan SC – Scheduled caste SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement ST – Scheduled tribe NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This social due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

District Sector Course Code Course Name Training Center Code Training Center Address E-Mail ID Mobile No 31St March 2019

Target Available Till District Sector Course Code Course Name Training Center Code Training Center Address E-mail ID Mobile No 31st March 2019 APPAREL, MADE-UPS & HOME ALIPURDUAR AMH/Q0301 Sewing Machine Operator PBSSD/TC/KVACAD/008 Vill+ P.O- Baragachia, P.S- Dhupguri, District- Alipurduar, Pin- 735204 [email protected] 9830170954 30 FURNISHING APPAREL, MADE-UPS & HOME ALIPURDUAR AMH/Q1001 Hand Embroiderer PBSSD/TC/TGSVSWS/001 Vill + PO-Taleswarguri, PS - Samuktala Alipurduar- 736206 West Bengal [email protected] 7872139885 30 FURNISHING APPAREL, MADE-UPS & HOME ALIPURDUAR AMH/Q1001 Hand Embroiderer PBSSD/TC/KVACAD/008 Vill+ P.O- Baragachia, P.S- Dhupguri, District- Alipurduar, Pin- 735204 [email protected] 9830170954 30 FURNISHING APPAREL, MADE-UPS & HOME ALIPURDUAR AMH/Q1947 Self Employed Tailor PBSSD/TC/TGSVSWS/001 Vill + PO-Taleswarguri, PS - Samuktala Alipurduar- 736206 West Bengal [email protected] 7872139885 60 FURNISHING APPAREL, MADE-UPS & HOME ALIPURDUAR AMH/Q1947 Self Employed Tailor PBSSD/TC/AASHRAY/005 Debinagar, ALIPURDUAR, Pin-736121 [email protected] 9831503562 300 FURNISHING APPAREL, MADE-UPS & HOME ALIPURDUAR AMH/Q1947 Self Employed Tailor PBSSD/TC/AMNDWS/018 Vill+P.O-Totopara,P.S-Madarihat,Dist-Alipurduar,Pin-735220 [email protected] 9830809606 90 FURNISHING APPAREL, MADE-UPS & HOME ALIPURDUAR AMH/Q1947 Self Employed Tailor PBSSD/TC/KVACAD/007 Vill- Birpara , P.O- Birpara, P.S- Dhupguri, District- Alipurduar, Pin- 735204 [email protected] 9830170954 90 FURNISHING APPAREL, MADE-UPS & HOME ALIPURDUAR AMH/Q1947 Self Employed Tailor PBSSD/TC/KVACAD/008 Vill+ P.O- Baragachia, P.S- Dhupguri, District- Alipurduar, Pin- 735204 [email protected] 9830170954 30 FURNISHING APPAREL, MADE-UPS & HOME ALIPURDUAR AMH/Q1947 Self Employed Tailor PBSSD/TC/PENSPVL/005 Plot No. -

Chapter: 4: Women in TG Panchayats: the State of Political

Chapter: 4: Women in TG Panchayats: The State of Political Empowerment 4.1. Introduction: 4.2. Political Empowerment of Women in India: A Brief Overview Chapter-4: Women in TG Panchayats 157 157 157 Chapter-4: Women in TG Panchayats 158 158 158 Chapter-4: Women in TG Panchayats 4.3. Empowerment of Women in the Panchayats of Jalpaiguri District: 6,227 sq. km 34, 01,173 (Toto, Rava, Mech etc) “Clouded Leopard” 188 158 159 159 159 Chapter-4: Women in TG Panchayats Table: 4.1: Brief Description of the Jalpaiguri District Description .1. Comparison between 2011 & 2001 Basic Statistics 2011 2001 Actual Population 3,869,675 3,401,173 Male 1,980,068 1,751,145 Female 1,889,607 1,650,028 Population Growth 13.77% 21.45% Area Sq. Km 6,227 6,227 Density/km2 621 546 Proportion to West Bengal Population 4.24% 4.24% Description . 2 Comparison between Rural & Urban Population, 2011 Rural Urban Population (%) 73.00 % 27.00 % Total Population 2,825,001 1,044,674 Male Population 1,445,791 534,277 Female Population 1,379,210 510,397 Sex Ratio 954 955 Child Sex Ratio (0-6) 950 943 Child Population (0-6) 340,662 104,363 Male Child(0-6) 174,677 53,704 Female Child(0-6) 165,985 50,659 Child Percentage (0-6) 12.06 % 9.99 % Male Child Percentage 12.08 % 10.05 % Female Child Percentage 12.03 % 9.93 % Literates 1,752,822 774,196 Male Literates 995,436 416,629 Female Literates 757,386 357,567 Average Literacy 70.55 % 82.33 % Male Literacy 78.31 % 86.69 % Female Literacy 62.43 % 77.78 % Source: http://www.census2011.co.in/census/district/2-jalpaiguri.html 160 160 160 Chapter-4: Women in TG Panchayats 1 http://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/prov_data_products_wb.html accessed 12th May, 2011 161 161 161 Chapter-4: Women in TG Panchayats Table: 4.2. -

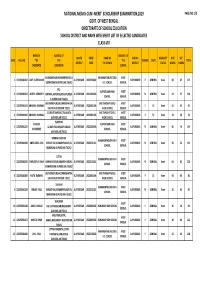

Alipurduar Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2019 PAGE NO.1/9 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL ANANDANAGAR,KAMAKHYAGURI,K KAMAKSHYAGURI GIRLS WEST 1 123193001012 ADITI SUTRADHAR ALIPURDUAR 19220710802 ALIPURDUAR F GENERAL None 60 67 127 UMARGRAM ALIPURDUAR 736202 H. S. SCHOOL BENGAL VILL‐ ALIPURDUAR HIGH WEST 2 123193001054 ADITYA DEBNATH BIRPARA,ALIPURDUAR,ALIPURDUA ALIPURDUAR 19221401804 ALIPURDUAR M GENERAL None 52 57 109 SCHOOL BENGAL R ALIPURDUAR 736121 JAYCHANDPUR,BHUTANIRGHAT,FA BHUTNIRGHAT GIRLS WEST 3 123193001013 ANAMIKA BARMAN ALIPURDUAR 19220401406 ALIPURDUAR F SC None 50 43 93 LAKATA ALIPURDUAR 735211 HIGH SCHOOL BENGAL 113,BHUTANIRGHAT,FALAKATA BHUTNIRGHAT GIRLS WEST 4 123193001094 ANAMIKA BARMAN ALIPURDUAR 19220401406 ALIPURDUAR F SC None 39 39 78 ALIPURDUAR 735211 HIGH SCHOOL BENGAL WARD NO ANIKESH ALIPURDUAR HIGH WEST 5 123193001137 12,ALIPURDUAR,ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR 19221401804 ALIPURDUAR M GENERAL None 60 74 134 MUKHERJEE SCHOOL BENGAL ALIPURDUAR 736121 SHIBBARI DAKSHIN KAMAKSHYAGURI HIGH WEST 6 123193001028 ANIRUDDHA DAS NARARTHALI,KAMAKHYAGURI,KU ALIPURDUAR 19220711301 ALIPURDUAR M GENERAL None 58 56 114 SCHOOL BENGAL MARGRAM ALIPURDUAR 736202 UTTAR KAMAKSHYAGURI HIGH WEST 7 123193001019 ANIRUDHYA SAHA KAMAKHYAGURI,KAMAKHYAGURI, -

Synopsis on Survey of Tea Gardens Conducted by Regional Labour Offices Under Jurisdiction of Joint Labour Commissioner, North Bengal Zone Contents

Synopsis on Survey of Tea Gardens Conducted by Regional Labour Offices under jurisdiction of Joint Labour Commissioner, North Bengal Zone Contents Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Introduction : …………………………………………. 2 to 3 2. Particulars of Tea Estates in North Bengal : …………………………………………. 4 to 5 3. Particulars of Employers (Management) : …………………………………………. 6 to 7 4. Operating Trade Unions : …………………………………………. 8 to 9 5. Area, Plantation & Yield : …………………………………………. 10 to 11 6. Family, Population, Non-Workers & Workers in Tea Estate : …………………………………………. 12 to 14 7. Man-days Utilized : …………………………………………. 15 to 15 8. Production of Tea : …………………………………………. 16 to 17 9. Financial & Other Support to Tea Estate : …………………………………………. 18 to 18 10. Housing : …………………………………………. 19 to 21 11. Electricity in Tea Estates : …………………………………………. 22 to 22 12. Drinking Water in Tea Estates : …………………………………………. 23 to 23 13. Health & Medical Facilities : …………………………………………. 24 to 24 14. Labour Welfare Officers : …………………………………………. 25 to 25 15. Canteen & Crèche : …………………………………………. 26 to 26 16. School & Recreation : …………………………………………. 27 to 27 17. Provident Fund : …………………………………………. 28 to 29 18. Wages, Ration, Firewood, Umbrella etc. : …………………………………………. 30 to 30 19. Gratuity : …………………………………………. 31 to 32 20. Bonus Paid to the Workmen of Tea Estate : …………………………………………. 33 to 33 21. Recommendation based on the Observation of Survey : …………………………………………. 34 to 38 Page 1 of 38 INTRODUCTION Very first time in the history of tea industry in North Bengal an in-depth survey has been conducted by the officers of Labour Directorate under kind and benevolent guardianship of Shri Purnendu Basu, Hon’ble MIC, Labour Department, Government of West Bengal and under candid and active supervision of Shri Amal Roy Chowdhury, IAS, Secretary of Labour Department (Labour Commissioner at the time of survey), Govt. -

(Plantation) Total : 40.02 112.13 Tea Board of India Licensing Department

Tea Board of India Licensing Department List of New Registration of Tea Estate during :from 01/01/1930 To 02/05/2008 Date: 02/05/2008 Page 1 of 121 Registration Date Name of the Company Area Applied Grant Area Mode of Leaf File No No Tea -Estate Processing Revenue District : AGARTALA Sub Division : AGARTALA Plantation Dist : AGARTALA 2659 14/12/1979 Tachi Tea Estate TEA PLANTATION CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY LTD. 40.02 112.13 NC/PART-361/LC (Plantation) Total : 40.02 112.13 Tea Board of India Licensing Department List of New Registration of Tea Estate during :from 01/01/1930 To 02/05/2008 Date: 02/05/2008 Page 2 of 121 Registration Date Name of the Company Area Applied Grant Area Mode of Leaf File No No Tea -Estate Processing Revenue District : AGARTALA Sub Division : AGARTALA Plantation Dist : Tripura 693 01/04/1953 ADARINI TEA ESTATE MR.M.K.CHOWDHURY 65 131.5 A-501/LC 188 01/04/1953 BRAHMAKUNDU TEA ESTATE BRAHMAKUNDU TEA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD 75 150.24 B-788/LC 170 18/02/1958 DURGABARI TEA ESTATE (T-2) DURGABARI TEA ESTATE WORKERS CO-OPERATIVE 44.53 68.01 N-8/LC/57(VOL-2) SOCIETY LTD. 135 18/06/1965 GOLOKPUR TEA ESTATE GOLOKPUR TEA CO. LTD 175 420 G-18/LC 116 01/04/1953 HARENDRANAGAR TEA ESTATE BORGANG TEA CO. (P) LTD., 203 264 H-789/LC 2567 20/04/1953 HARIDASPUR TEA ESTATE TRIPURA PRODUCE CO. 21.67 38.45 H-601/LC 308 11/03/1961 LEELAGARH TEA ESTATE LEELAGARH CHA BAGAN SRAMIK SAMABAYA SAMITY 36.43 137.4 L-16/LC LTD.