Human in US Science Fiction, 1938-1950 A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(C) 1978 by Random House, Inc. Introduction: "The Dean of Science

A Del Rey Book - Published by Ballantine Books Copyright (c) 1978 by Random House, Inc. Introduction: "The Dean of Science Fiction" Copyright (c) 1978 by J. J. Pierce All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Ballantine Books of Canada, Ltd., Toronto, Canada. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 78-52210 ISBN 0-345-25800-2 Manufactured in the United States of America First Edition: April 1978 Cover art by H. R. Van Dongen ACKNOWLEDGMENTS "Sidewise in Time," copyright (c) 1934 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Stories, June 1934. "Proxima Centauri," co~yright (c) 1935 by Street & Smith Pub.. lications, Inc., for Astounding Stories, March 1935. - "The Fourth-dimensional Demonstrator," copyright (c) 1935 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Stories, December 1935. "First Contact," copyright (c) 1945 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, May 1945. "The Ethical Equations," copyright (c) 1945 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, June 1945. "Pipeline to Pluto," copyright (c) 1945 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, August 1945. "The Power," copyright (c) 1945 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, September 1945. "A Logic Named Joe," copyright (c) 1946 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, March 1946. "Symbiosis," copyright (c) 1947 for Collier's Magazine, January 1947. "The Strange Case of John Kingman," copyright (c) 1948 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, May 1948. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

SFRA Newsletter Published Ten Times a Vear Iw the Science Fiction Research Associa Tion

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 3-1-1989 SFRA ewN sletter 165 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 165 " (1989). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 110. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/110 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The SFRA Newsletter Published ten times a vear Iw The Science Fiction Research Associa tion. C:opyrightf'.' 1l)8~ by the SFRA. Address editorial correspon dence to SFRA Newslcller. English Dept., Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton. FL ::n,n I (Tel. 407-3()7-3838). Editor: Robert A. Collins: Associate Editor: Catherine Fischer: R('l'iCiv Editor: Rob Latham: Fillll Editor: Ted Krulik; Book Neil'S Editor: Martin A. Schneider: EditOlial Assistant: .Jeanette Lawson. Send changes of address to the Secretary. enquiries concerning subscriptions to the Treasurer, listed below. Past Presidents of SFRA Thomas D. Clare son (1970-76) SFRA Executive Arthur o. Lewis,.Jr. (1977-78) Committee .Joe De Bolt (1979-80) .J ames Gunn (1981-82) Patricia S. Warrick (1983-84) Donald M. Hassler (J985-8() President Elizabeth Anne Hull Past EditOl'S of the Newsletter Liberal Arts Division Fred Lerner (1971-74) William Rainey Harper College Beverly Friend (1974-78) Palatine. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

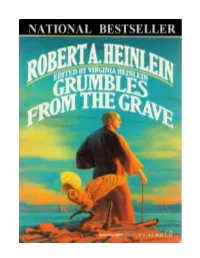

Grumbles from the Grave

GRUMBLES FROM THE GRAVE Robert A. Heinlein Edited by Virginia Heinlein A Del Rey Book BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK For Heinlein's Children A Del Rey Book Published by Ballantine Books Copyright © 1989 by the Robert A. and Virginia Heinlein Trust, UDT 20 June 1983 All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint the following material: Davis Publications, Inc. Excerpts from ten letters written by John W. Campbell as editor of Astounding Science Fiction. Copyright ® 1989 by Davis Publications, Inc. Putnam Publishing Group: Excerpt from the original manuscript of Podkayne of Mars by Robert A. Heinlein. Copyright ® 1963 by Robert A. Heinlein. Reprinted by permission of the Putnam Publishing Group. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 89-6859 ISBN 0-345-36941-6 Manufactured in the United States of America First Hardcover Edition: January 1990 First Mass Market Edition: December 1990 CONTENTS Foreword A Short Biography of Robert A. Heinlein by Virginia Heinlein CHAPTER I In the Beginning CHAPTER II Beginnings CHAPTER III The Slicks and the Scribner's Juveniles CHAPTER IV The Last of the Juveniles CHAPTER V The Best Laid Plans CHAPTER VI About Writing Methods and Cutting CHAPTER VII Building CHAPTER VIII Fan Mail and Other Time Wasters CHAPTER IX Miscellany CHAPTER X Sales and Rejections CHAPTER XI Adult Novels CHAPTER XII Travel CHAPTER XIII Potpourri CHAPTER XIV Stranger CHAPTER XV Echoes from Stranger AFTERWORD APPENDIX A Cuts in Red Planet APPENDIX B Postlude to Podkayne of Mars—Original Version APPENDIX C Heinlein Retrospective, October 6, 1988 Bibliography Index FOREWORD This book does not contain the polished prose one normally associates with the Heinlein stories and articles of later years. -

1960 Imhwoftld Sc'tnce Fieri on Co*V*M5'on

No. 2 PiTrcoW > • • > • PITTSBURGH . SEPTEMBER 3, 4, 5, 1960 iMhWoftlD Sc'tNCE fieri ON Co*V*M5'ON CARE OF DIRCE S. ARCHER • 1*53 BARNSDALE STREET • PITTSBURGH 17, PA. SECOND PROGRESS REPORT - MAY 1960 JOURNAL of 18th WORLD SCIENCE FICTION CONVENTION - VOL. 18, NO. 2 Subscription included with Convention membership: $2.00, payable to the PITTCON Treasurer (overseas: $1.00). Advertising copy for the Third Progress Report must reach the Committee by June 15. PITTCON COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN: Dirce S. Archer VICE CHAIRMAN: Ray Smith SECRETARY: Bob Hyde TREASURER: P. Schuyler Miller EXECUTIVE SECRETARY: Ellen Parkes PUBLICITY & PUBLIC RELATIONS: Ed Wood PARLIAMENTARIAN: L. Sprague de Camp FANZINE CONSULTANT: Lynn Hickman SPECIAL CONSULTANTS: Howard Devore and Earl Kemp OVERSEAS REPRESENTATIVES: Kenneth F. Slater .. United Kingdom Roger Dard............... Australia REMEMBER THESE DATES] 15 JUNE 1960; COPY DEADLINE for the THIRD PROGRESS REPORT 25 & 26 JUNE 1960: MIDWESTCON #11 at North Plaza Motel, 7911 Reading Rd., Cincinnati 37, Ohio. Details from Don Ford, Box 19T, Wards Corner Rd., Loveland, Ohio. (Make your Motel reservation early]) 1 JULY 1960: COPY DEADLINE for the PITTCON PROGRAM 2, 3 & 4 JULY i960; WESTERCON (BOYCON) at Boise, Idaho. Check with Guy Terwilliger, 1412 Albright St., Boise, Idaho for details. Guest of Honor: Rog Phillips. 15 JULY 1960: Last day to mail your HUGO BALLOT. 27 AUGUST 1960: Last day to mail your ADVANCE BANQUET RESERVATIONS. Use the enclosed Reservation Card. 3, 4 & 5 SEPTEMBER 1960: The PITTCON at the PENN-SHERATON HOTEL, William Penn Place, Pittsburgh 22, Pa. Registra tion: $2.00 ($1.00 overseas). Use the enclosed card to make your hotel reservation at the special rate. -

Forte JA T 2010.Pdf (404.2Kb)

“We Werenʼt Kidding” • Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 By Joseph A. Forte Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Robert P. Stephens (chair) Marian B. Mollin Amy Nelson Matthew H. Wisnioski May 03, 2010 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Astounding Science-Fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr., sci-fi, science fiction, pulp magazines, culture, ideology, Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, A. E. van Vogt, American exceptionalism, capitalism, 1939 Worldʼs Fair, Cold War © 2010 Joseph A. Forte “We Werenʼt Kidding” Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 Joseph A. Forte ABSTRACT In 1971, Isaac Asimov observed in humanity, “a science-important society.” For this he credited the man who had been his editor in the 1940s during the period known as the “golden age” of American science fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr. Campbell was editor of Astounding Science-Fiction, the magazine that launched both Asimovʼs career and the golden age, from 1938 until his death in 1971. Campbell and his authors set the foundation for the modern sci-fi, cementing genre distinction by the application of plausible technological speculation. Campbell assumed the “science-important society” that Asimov found thirty years later, attributing sci-fi ascendance during the golden age a particular compatibility with that cultural context. On another level, sci-fiʼs compatibility with “science-important” tendencies during the first half of the twentieth-century betrayed a deeper agreement with the social structures that fueled those tendencies and reflected an explication of modernity on capitalist terms. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Vop #135 / 3 College

#135 Visions of Paradise #135 Contents The Passing Scene................................................................................................page 3 November 2008 Wondrous Stories................................................................................................page 5 Galactic Empires ... Farmer in the Sky ... Heinlein’s Children . Slick Willie’s Used Car World.............................................................…...........page 9 Part One On the Lighter Side............................................................................................page 16 Jokes by Bill Sabella _\\|//_ ( 0_0 ) ___________________o00__(_)__00o_________________ Robert Michael Sabella E-mail [email protected] Personal blog: http://adamosf.blogspot.com/ Sfnal blog: http://visionsofparadise.blogspot.com/ Fiction blog: http://bobsabella.livejournal.com/ Available online at http://efanzines.com/ Copyright ©November, 2008, by Gradient Press Available for trade, letter of comment or request Artwork Sheryl Birkhead ………………. cover Brad Foster ………………….page 8 The Passing Scene November 2008 Jean and I ended October by staying home on Halloween instead of going shopping. However, we had our usual small total of about 10 trick or treaters, so it was a relaxing night. The next day, after going to the YMCA in the morning, we had a quick lunch at a diner (which used to be as prevalent in New Jersey as mushrooms in a field, but recently have diminished to one every few towns) followed by a ride to Newark Airport to pick up Mark and Kate who flew back from a week at Disney World. They had a good week there, climaxed by a huge Halloween party at the Magic Kingdom so that they came home with two huge bags filled with candy. November is the month of the Indian Culture Club’s annual Family Diwali Dinner, and it was very successful. The officers did a good job planning it, the families brought lots of food, and everybody enjoyed themselves. -

Selected Scifi 201102.Xlsx

Selected Used SciFi Books- Subject to availability - Call/email store to receive purchasing link ([email protected] 540206-2505) StorePri AuthorsLast Title EAN Publisher ce Cross-Currents: Storm Season, The Face of Chaos, Abbey, Robert Lynn Asprin and Lynn B000GPXLOQ Nelson Doubleday,. $8.00 and Wings of Omen Adams, Douglas Life, The Universe and Everything 9780517548745 Harmony Books $8.00 Adams, Douglas Mostly Harmless 9781127539635 BALLANTINE BOOKS $15.00 Adams, Douglas So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish 9780795326516 HARMONY BOOKS $6.00 Adams, Douglas The Restaurant at the End of the Universe 9780517545355 Harmony $8.00 Adams, Richard MAIA 9780394528571 Knopf $8.00 Alan, Foster Dean Midworld B001975ZFI Ballentine $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Helliconia Summer (Helliconia Trilogy, Book Two) 9781111805173 Atheneum / $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Non-Stop B0057JRIV8 Carroll & Graf $10.00 Aldiss, Brian Wilson Helliconia Winter (Helliconia, 3) 9780689115417 Atheneum $7.00 Allen, Roger E. Isaac Asimov's Inferno 9780441000234 Ace Trade $6.00 Allen, Roger Macbride Isaac Asimov's Utopia 9781857982800 Orion Publishing Co $8.00 Allston, Aaron Enemy lines (Star wars, The new Jedi order) 9780739427774 Science Fiction $15.00 Anderson, Kevin J and Rebecca The Rise of the Shadow Academy 9781568652115 Guild America $15.00 Moesta Anderson, Kevin J,Herbert, Brian Hunters of Dune 9780765312921 Tor Books $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. A Forest of Stars: The Saga of Seven Suns Book 2 9780446528719 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Darksaber (Star Wars) 9780553099744 Spectra $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Hidden Empire: The Saga of Seven Suns - Book 1 9780446528627 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. -

Evitable Conflicts, Inevitable Technologies?

LCH0010.1177/1743872113509443Law, Culture and the HumanitiesKerr and Szilagyi 509443research-article2014 LAW, CULTURE AND THE HUMANITIES MINI SYMPOSIUM: SCIENCE, SCIENCE FICTION AND INTERNATIONAL LAW Law, Culture and the Humanities 2018, Vol. 14(1) 45 –82 Evitable Conflicts, Inevitable © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: Technologies? The Science sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/1743872113509443DOI: 10.1177/1743872113509443 and Fiction of Robotic journals.sagepub.com/home/lch Warfare and IHL Ian Kerr University of Ottawa, Canada Katie Szilagyi McCarthy Tétrault LLP, Canada Abstract This article contributes to a special symposium on science fiction and international law, examining the blurry lines between science and fiction in the policy discussions concerning the military use of lethal autonomous robots. In response to projects that attempt to build military robots that comport with international humanitarian law [IHL], we investigate whether and how the introduction of lethal autonomous robots might skew international humanitarian norms. Although IHL purports to be a technologically-neutral approach to calculating a proportionate, discriminate, and militarily necessary response, we contend that it permits a deterministic mode of thinking, expanding the scope of that which is perceived of as “necessary” once the technology is adopted. Consequently, we argue, even if lethal autonomous robots comport with IHL, they will operate as a force multiplier of military necessity, thus skewing the proportionality