Frequently Asked Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecosystem Status and Trends Report for the Strait of Georgia Ecozone

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2010/010 Document de recherche 2010/010 Ecosystem Status and Trends Report Rapport de l’état des écosystèmes et for the Strait of Georgia Ecozone des tendances pour l’écozone du détroit de Georgie Sophia C. Johannessen and Bruce McCarter Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Institute of Ocean Sciences 9860 W. Saanich Rd. P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, B.C. V8L 4B2 This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of des écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle the day in the time frames required and the traite des problèmes courants selon les documents it contains are not intended as échéanciers dictés. Les documents qu’elle definitive statements on the subjects addressed contient ne doivent pas être considérés comme but rather as progress reports on ongoing des énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais investigations. plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit Secretariat. envoyé au Secrétariat. This document is available on the Internet at: Ce document est disponible sur l’Internet à: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas/ ISSN 1499-3848 (Printed / Imprimé) ISSN 1919-5044 (Online / En ligne) © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2010 © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights 1 Drivers of change 2 Status and trends indicators 2 1. -

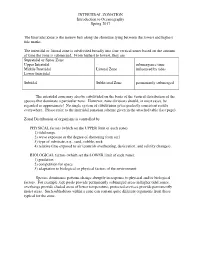

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The Intertidal Zone is the narrow belt along the shoreline lying between the lowest and highest tide marks. The intertidal or littoral zone is subdivided broadly into four vertical zones based on the amount of time the zone is submerged. From highest to lowest, they are Supratidal or Spray Zone Upper Intertidal submergence time Middle Intertidal Littoral Zone influenced by tides Lower Intertidal Subtidal Sublittoral Zone permanently submerged The intertidal zone may also be subdivided on the basis of the vertical distribution of the species that dominate a particular zone. However, zone divisions should, in most cases, be regarded as approximate! No single system of subdivision gives perfectly consistent results everywhere. Please refer to the intertidal zonation scheme given in the attached table (last page). Zonal Distribution of organisms is controlled by PHYSICAL factors (which set the UPPER limit of each zone): 1) tidal range 2) wave exposure or the degree of sheltering from surf 3) type of substrate, e.g., sand, cobble, rock 4) relative time exposed to air (controls overheating, desiccation, and salinity changes). BIOLOGICAL factors (which set the LOWER limit of each zone): 1) predation 2) competition for space 3) adaptation to biological or physical factors of the environment Species dominance patterns change abruptly in response to physical and/or biological factors. For example, tide pools provide permanently submerged areas in higher tidal zones; overhangs provide shaded areas of lower temperature; protected crevices provide permanently moist areas. Such subhabitats within a zone can contain quite different organisms from those typical for the zone. -

Spring Bloom in the Central Strait of Georgia: Interactions of River Discharge, Winds and Grazing

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 138: 255-263, 1996 Published July 25 Mar Ecol Prog Ser I l Spring bloom in the central Strait of Georgia: interactions of river discharge, winds and grazing Kedong yinl,*,Paul J. Harrisonl, Robert H. Goldblattl, Richard J. Beamish2 'Department of Oceanography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 124 'pacific Biological Station, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Nanaimo, British Columbia, Canada V9R 5K6 ABSTRACT: A 3 wk cruise was conducted to investigate how the dynamics of nutrients and plankton biomass and production are coupled with the Fraser River discharge and a wind event in the Strait of Georgia estuary (B.C.,Canada). The spring bloom was underway in late March and early Apnl, 1991. in the Strait of Georgia estuary. The magnitude of the bloom was greater near the river mouth, indicat- ing an earher onset of the spring bloom there. A week-long wind event (wind speed >4 m S-') occurred during April 3-10 The spring bloom was interrupted, with phytoplankton biomass and production being reduced and No3 in the surface mixing layer increasing at the end of the wind event. Five days after the lvind event (on April 15),NO3 concentrations were lower than they had been at the end of the wind event, Indicating a utilization of NO3 during April 10-14. However, the utilized NO3 did not show up in phytoplankton blomass and production, which were lower than they had been at the end (April 9) of the wind event. During the next 4 d, April 15-18, phytoplankton biomass and production gradu- ally increased, and No3 concentrations in the water column decreased slowly, indicating a slow re- covery of the spring bloom Zooplankton data indicated that grazing pressure had prevented rapid accumulation of phytoplankton biomass and rapid utilization of NO3 after the wind event and during these 4 d. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

A Nitrogen Budget for the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia, with Emphasis on Particulate Nitrogen and Dissolved Inorganic Nitrogen

Biogeosciences, 10, 7179–7194, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/7179/2013/ doi:10.5194/bg-10-7179-2013 Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. A nitrogen budget for the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia, with emphasis on particulate nitrogen and dissolved inorganic nitrogen J. N. Sutton1,2, S. C. Johannessen1, and R. W. Macdonald1 1Institute of Ocean Sciences, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 9860 West Saanich Road, P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, British Columbia, V8L 4B2, Canada 2Department of Earth and Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, California, 94720, USA Correspondence to: J. N. Sutton ([email protected]) Received: 6 March 2013 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 23 April 2013 Revised: 29 September 2013 – Accepted: 10 October 2013 – Published: 12 November 2013 Abstract. Balanced budgets for dissolved inorganic N (DIN) 1 Introduction and particulate N (PN) were constructed for the Strait of Georgia (SoG), a semi-enclosed coastal sea off the west coast of British Columbia, Canada. The dominant control on the The nitrogen (N) cycle is a crucial underpinning of marine N budget is the advection of DIN into and out of the SoG biological productivity (Gruber and Galloway, 2008). Dur- via Haro Strait. The annual influx of DIN by advection from ing the past 150 yr, the global N cycle has been dramati- the Pacific Ocean is 29 990 (±19 500) Mmol yr−1. The DIN cally changed by human activities that have loaded reactive N flux advected out of the SoG is 24 300 (±15 500) Mmol yr−1. into ecosystems in amounts that rival natural sources (Rabal- Most of the DIN that enters the SoG (∼ 23 400 Mmol yr−1) ais, 2002; Galloway et al., 2004). -

British Columbia Groundfish Fisheries and Their Investigations in 1999

British Columbia Groundfish Fisheries And Their Investigations in 1999 April 2000 Prepared for the 41st Annual Meeting of the Technical Sub- committee of the Canada-United States Groundfish Committee May 9-11, 1999. Nanaimo,B.C. CANADA by M. W. Saunders K. L. Yamanaka Fisheries and Oceans Canada Science Branch Pacific Biological Station Nanaimo, British Columbia V9R 5K6 - 2 - REVIEW OF AGENCY GROUNDFISH RESEARCH, STOCK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT A. Agency overview Fisheries and Oceans Canada (FOC), Science Branch, operates three facilities in the Pacific Region: the Pacific Biological Station (PBS), the Institute of Ocean Sciences (IOS) and the West Vancouver Laboratory (WVL). These facilities are located in Nanaimo, Sidney and North Vancouver, B.C., respectively. Division Heads at these facilities report to the Regional Director of Science (RDS). Personnel changes within the Region Science Branch in 1999 include the appointments of Dr. Laura Richards as the Acting RDS and Mr. Ted Perry as the Head of the Stock Assessment Division (STAD). The current Division Heads in Science Branch are: Stock Assessment Division Mr. T. Perry Marine Environment and Habitat Science Dr. J. Pringle Ocean Science and Productivity Mr. R. Brown Aquaculture Dr. D. Noakes Groundfish research and stock assessments are conducted primarily in two sections of the Stock Assessment Division, Fish Population Dynamics (Sandy McFarlane, Head) and Assessment Methods (Jeff Fargo, Head). The Assessment Methods Section includes the Fish Ageing Lab. A reorganization is imminent and the plan is to convene a single Groundfish Section and a new Pelagics Section. The section heads are yet to be determined. Management of groundfish resources is the responsibility of the Pacific Region Groundfish Coordinator (Ms. -

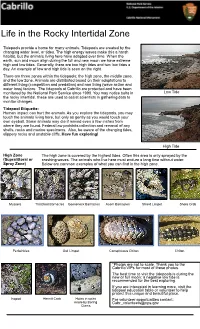

Life in the Intertidal Zone

Life in the Rocky Intertidal Zone Tidepools provide a home for many animals. Tidepools are created by the changing water level, or tides. The high energy waves make this a harsh habitat, but the animals living here have adapted over time. When the earth, sun and moon align during the full and new moon we have extreme high and low tides. Generally, there are two high tides and two low tides a day. An example of low and high tide is seen on the right. There are three zones within the tidepools: the high zone, the middle zone, and the low zone. Animals are distributed based on their adaptations to different living (competition and predation) and non living (wave action and water loss) factors. The tidepools at Cabrillo are protected and have been monitored by the National Park Service since 1990. You may notice bolts in Low Tide the rocky intertidal, these are used to assist scientists in gathering data to monitor changes. Tidepool Etiquette: Human impact can hurt the animals. As you explore the tidepools, you may touch the animals living here, but only as gently as you would touch your own eyeball. Some animals may die if moved even a few inches from where they are found. Federal law prohibits collection and removal of any shells, rocks and marine specimens. Also, be aware of the changing tides, slippery rocks and unstable cliffs. Have fun exploring! High Tide High Zone The high zone is covered by the highest tides. Often this area is only sprayed by the (Supralittoral or crashing waves. -

Spatial Patterns of Macrozoobenthos Assemblages in a Sentinel Coastal Lagoon: Biodiversity and Environmental Drivers

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Spatial Patterns of Macrozoobenthos Assemblages in a Sentinel Coastal Lagoon: Biodiversity and Environmental Drivers Soilam Boutoumit 1,2,* , Oussama Bououarour 1 , Reda El Kamcha 1 , Pierre Pouzet 2 , Bendahhou Zourarah 3, Abdelaziz Benhoussa 1, Mohamed Maanan 2 and Hocein Bazairi 1,4 1 BioBio Research Center, BioEcoGen Laboratory, Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed V University in Rabat, 4 Avenue Ibn Battouta, Rabat 10106, Morocco; [email protected] (O.B.); [email protected] (R.E.K.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (H.B.) 2 LETG UMR CNRS 6554, University of Nantes, CEDEX 3, 44312 Nantes, France; [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (M.M.) 3 Marine Geosciences and Soil Sciences Laboratory, Associated Unit URAC 45, Faculty of Sciences, Chouaib Doukkali University, El Jadida 24000, Morocco; [email protected] 4 Institute of Life and Earth Sciences, Europa Point Campus, University of Gibraltar, Gibraltar GX11 1AA, Gibraltar * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This study presents an assessment of the diversity and spatial distribution of benthic macrofauna communities along the Moulay Bousselham lagoon and discusses the environmental factors contributing to observed patterns. In the autumn of 2018, 68 stations were sampled with three replicates per station in subtidal and intertidal areas. Environmental conditions showed that the range of water temperature was from 25.0 ◦C to 12.3 ◦C, the salinity varied between 38.7 and 3.7, Citation: Boutoumit, S.; Bououarour, while the average of pH values fluctuated between 7.3 and 8.0. -

Intertidal Sand and Mudflats & Subtidal Mobile

INTERTIDAL SAND AND MUDFLATS & SUBTIDAL MOBILE SANDBANKS An overview of dynamic and sensitivity characteristics for conservation management of marine SACs M. Elliott. S.Nedwell, N.V.Jones, S.J.Read, N.D.Cutts & K.L.Hemingway Institute of Estuarine and Coastal Studies University of Hull August 1998 Prepared by Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) for the UK Marine SACs Project, Task Manager, A.M.W. Wilson, SAMS Vol II Intertidal sand and mudflats & subtidal mobile sandbanks 1 Citation. M.Elliott, S.Nedwell, N.V.Jones, S.J.Read, N.D.Cutts, K.L.Hemingway. 1998. Intertidal Sand and Mudflats & Subtidal Mobile Sandbanks (volume II). An overview of dynamic and sensitivity characteristics for conservation management of marine SACs. Scottish Association for Marine Science (UK Marine SACs Project). 151 Pages. Vol II Intertidal sand and mudflats & subtidal mobile sandbanks 2 CONTENTS PREFACE 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 I. INTRODUCTION 17 A. STUDY AIMS 17 B. NATURE AND IMPORTANCE OF THE BIOTOPE COMPLEXES 17 C. STATUS WITHIN OTHER BIOTOPE CLASSIFICATIONS 25 D. KEY POINTS FROM CHAPTER I. 27 II. ENVIRONMENTAL REQUIREMENTS AND PHYSICAL ATTRIBUTES 29 A. SPATIAL EXTENT 29 B. HYDROPHYSICAL REGIME 29 C. VERTICAL ELEVATION 33 D. SUBSTRATUM 36 E. KEY POINTS FROM CHAPTER II 43 III. BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGICAL FUNCTIONING 45 A. CHARACTERISTIC AND ASSOCIATED SPECIES 45 B. ECOLOGICAL FUNCTIONING AND PREDATOR-PREY RELATIONSHIPS 53 C. BIOLOGICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL INTERACTIONS 58 D. KEY POINTS FROM CHAPTER III 65 IV. SENSITIVITY TO NATURAL EVENTS 67 A. POTENTIAL AGENTS OF CHANGE 67 B. KEY POINTS FROM CHAPTER IV 74 V. SENSITIVITY TO ANTHROPOGENIC ACTIVITIES 75 A. -

Psc Draft1 Bc

138°W 136°W 134°W 132°W 130°W 128°W 126°W 124°W 122°W 120°W 118°W N ° 2 6 N ° 2 DR A F T To navigate to PSC Domain 6 1/26/07 maps, click on the legend or on the label on the map. Domain 3: British Columbia R N ° k 0 6 e PSC Region N s ° l Y ukon T 0 e 6 A rritory COBC - Coastal British Columbia Briti sh Columbia FRTH - Fraser R - Thompson R GST - Georgia Strait . JNST - Johnstone Strait R ku NASK - Nass R - Skeena R Ta N QCI - Queen Charlotte Islands ° 8 5 TRAN N TRAN - Transboundary Rivers in Canada ° 8 r 5 ive R WCVI - Western Vancouver Island e in r !. City/Town ik t e v S i Major River R t u k Scale = 1:6,750,000 Is P Miles N ° 0 30 60 120 180 January 2007 6 A B 5 N ° r 6 i 5 C t i s . A h R Alaska l I b C s e F s o a NASK r l N t u a r m I e v S i C tu b R a i rt a N a ° Prince Rupert en!. R 4 ke 5 !. S Terrace iv N e ° r 4 O F 5 !. ras er C H Prince George R e iv c e QCI a r t E e . r R S ate t kw r lac Quesnel A a B !. it D e an R. N C F N COBC h FRTH ° i r 2 lc a 5 o N s ti ° e n !. -

Offshore Oil & Gas in BC: a Chronology of Activity

Offshore Oil & Gas in BC: A Chronology of Activity 1913-1915 First well drilled in the Queen Charlotte Basin by BC Oilfields Limited at Tian Bay, western Graham Island. Reported minor gas and oil shows below 1220 feet. 1949-1951 Eight wells were drilled onshore Graham Island. No discoveries were reported. 1959 British Columbia declares a Crown reserve over oil and gas resources in the area east of a line running north-south three miles seaward of Queen Charlotte Islands and Vancouver Island. Under the Petroleum and Natural Gas Act, exploration permits over oil and gas in a Crown reserve can only be granted through public auction. 1962-1966 British Columbia Crown reserve over offshore oil and gas resources is cancelled to encourage companies to apply for exploration permits. 1966 British Columbia reinstates the Crown reserve over offshore oil and gas resources to the area beginning at the low-water mark seaward to the outer limits of Canada's Territorial Sea and to that area of the Continental Shelf capable of being exploited. 1966-1969 Canada withholds exploration approval in the Strait of Georgia until a federal-private study on the effects of seismic exploration on fish stocks is complete. 1967 British Columbia declares a Crown reserve over offshore mineral and placer minerals in same area as offshore oil and gas Crown reserve. 1967 The Supreme Court of Canada decides that the Territorial Sea off British Columbia, outside of bays, harbours and inland waters, belongs to Canada. 1967 Shell Canada begins a drilling program off Barkley Sound, Vancouver Island. Over the next two years, 14 wells are drilled in the offshore in the region from Barkley Sound north through Queen Charlotte Sound and Hecate Strait. -

Wave Energy and Intertidal Productivity (Leaf Area Index/Myfilus Californianus/Postelsia/Rocky Shore/Zonation) EGBERT G

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 84, pp. 1314-1318, March 1987 Ecology Wave energy and intertidal productivity (leaf area index/Myfilus californianus/Postelsia/rocky shore/zonation) EGBERT G. LEIGH, JR.*, ROBERT T. PAINEt, JAMES F. QUINNt, AND THOMAS H. SUCHANEKt§ *Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 2072, Balboa, Panama; tDepartment of Zoology NJ-15, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195; tDivision of Environmental Studies, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA 95616; and §Bodega Marine Laboratory, P. 0. Box 247, Bodega Bay, CA 94923 Contributed by Robert T. Paine, October 20, 1986 ABSTRACT In the northeastern Pacific, intertidal zones we estimate standing crop and productivity in different zones of the most wave-beaten shores receive more energy from of exposed and sheltered rocky shores of Tatoosh Island (480 breaking waves than from the sun. Despite severe mortality 19' N, 1240 40' W), showing that intertidal productivity is from winter storms, communities at some wave-beaten sites much higher in wave-beaten settings. Finally, we consider produce an extraordinary quantity of dry matter per unit area the various roles waves may play in enhancing the produc- of shore per year. At wave-beaten sites of Tatoosh Island, WA, tivity of intertidal organisms. sea palms, Postelsia palmaeformis, can produce >10 kg of dry matter, or 1.5 x 108 J. per m2 in a good year. Extraordinarily METHODS productive organisms such as Postelsia are restricted to wave- The Power Supplied by Breaking Waves. Calculating the beaten sites. Intertidal organisms cannot transform wave power carried by waves in the open ocean. Waves generated energy into chemical energy, as photosynthetic plants trans- anywhere in the ocean-dissipate most of their energy against form solar energy, nor can intertidal organisms "harness" some shore as surf (13, 14).