In Re Carnival Corp. Securities Litigation 20-CV-22202

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2019 Issue 118 Price $9.35 (Incl Gst)

22ND YEAR OF PUBLICATION ESTABLISHED 1998 APRIL 2019 ISSUE 118 PRICE $9.35 (INCL GST) Andrea Bocelli (right) and son Matteo Bocelli Hollywood Icon Sophia Loren Cirque du Soleil A Starry, Starry Night in Southhampton NAMING CEREMONY OF MSC BELLISSIMA Featuring a comprehensive coverage of Global Cruising for Cruise Passengers, the Trade and the Industry www.cruisingnews.com discover what makes Princess #1 cruise line in australia* 4 years running New Zealand 13 Australia & New Zealand 12 Majestic Princess® | Ruby Princess® Nights Majestic Princess® Nights Sydney Bay of Islands Sydney South Pacific Ocean AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIA 2015 - 2018 South Pacific Auckland Ocean Melbourne Auckland Tauranga Tauranga NEW ZEALAND Tasman Tasman Wellington Hobart Sea NEW ZEALAND Sea Akaroa Akaroa Fiordland National Park Dunedin Scenic cruising Dunedin Fiordland National Park (Port Chalmers) Scenic cruising (Port Chalmers) 2019 DEPARTURES 30 Sep, 1 Nov, 14 Nov, 22 Nov 2019 DEPARTURES 15 Dec, 27 DecA 2020 DEPARTURES 8 Jan, 11 Feb, 24 FebA, 8 Mar A Itinerary varies: operates in reverse order 2014 - 2018 A Itinerary varies: operates in reverse order *As voted by Cruise Passenger Magazine, Best Ocean Cruise Line Overall 2015-2018 BOOK NOW! Visit your travel agent | 1300 385 631 | www.princess.com 22ND YEAR OF PUBLICATION ESTABLISHED 1998 APRIL 2019 ISSUE 118 PRICE $9.35 (INCL GST) The Cruise Industry continues to prosper. I attended the handover and naming ceremony recently for the latest MSC ship, MSC Bellissima. It was an incredible four day adventure. Our front cover reveals the big event and you can read reports on page 5 and from page 34. -

Sailings-Schedule.Pdf

Sailings Schedule 2017 - 2019 Table of Contents Baltimore ............................................................. 3 Barcelona ............................................................. 4 Charleston ............................................................. 5 Fort Lauderdale ............................................................. 8 Galveston ............................................................. 11 Honolulu ............................................................. 14 Jacksonville ............................................................. 15 Los Angeles ............................................................. 16 Miami ............................................................. 19 Mobile ............................................................. 24 New Orleans ............................................................. 25 New York ............................................................. 27 Norfolk ............................................................. 28 Port Canaveral ............................................................. 29 San Juan ............................................................. 33 Seattle ............................................................. 34 Tampa ............................................................. 35 Vancouver ............................................................. 37 2 Baltimore SHIPS: PRIDE® ITINERARIES: THE BAHAMAS, BERMUDA, EASTERN CARIBBEAN, FLORIDA & THE BAHAMAS, SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN CARNIVAL PRIDE® CARNIVAL PRIDE® CARNIVAL PRIDE® -

Impact of Norovirus in the Cruise Ship Industry

Impact of Norovirus in the cruise ship industry Dr Daniel Stock Professor Susanne Becken Dr Chris Davis Griffith Institute for Tourism Research Report Series Report No 8 September 2015 griffith.edu.au/griffith-institute-tourism Impact of Norovirus in the cruise ship industry Dr Daniel Stock Professor Susanne Becken Dr Chris Davis Griffith Institute for Tourism Research Report No 8 September 2015 ISSN 2203-4862 (Print) ISSN 2203-4870 (Online) ISBN 978-1-922216-86-1 Griffith University, Queensland, Australia 2 Industry Reference Panel or Peer Review Panel Wendy London, Cruise Industry Specialist, New Zealand © Griffith Institute for Tourism, Griffith University 2015 This information may be copied or reproduced electronically and distributed to others without restriction, provided the Griffith Institute for Tourism (GIFT) is acknowledged as the source of information. Under no circumstances may a charge be made for this information without the express permission of GIFT, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia. GIFT Research Report Series URL: www.griffith.edu.au/business-government/griffith-institute-tourism/publications/research- report-series Organisations involved Dr Danny Stock, Research Assistant, Griffith Institute for Tourism, Griffith University Professor Susanne Becken, Director, Griffith Institute for Tourism, Griffith University Dr Chris Davis, General Manager, Institute for Glycomics, Griffith University About Griffith University Griffith University is a top ranking University, based in South East Queensland, Australia. Griffith University hosts the Griffith Institute for Tourism, a world-leading institute for quality research into tourism. Through its activities and an external Advisory Board, the Institute links university-based researchers with the business sector and organisations, as well as local, state and federal government bodies. -

Ebook Download the Sunshine Cruise Company Ebook

THE SUNSHINE CRUISE COMPANY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Niven | 368 pages | 24 Mar 2016 | Cornerstone | 9780099592341 | English | London, United Kingdom Carnival Sunshine Cruise Ship Deals | KAYAK BlueIguana Cantina. Library Bar. Carnival Sunshine. Sofa and coffee table. Desk and seat. Full bathroom with shower. Private aft-facing extended balcony with patio chairs and table. Stateroom Amenities : Modified for guests with wheelchairs. Carnival Comfort Collection. Mini Bar. Safety Deposit Box. Individual Climate Control. Balcony Stateroom Cabin type: balcony 8A Two twin beds convert to king. Sofa and Coffee Table. Desk and Seat. Private balcony with patio chairs and table. Stateroom Amenities : hour stateroom service. Private wrap-around balcony with patio chairs and table. Premium Balcony Cabin type: balcony 9B Two twin beds convert to king and single sofa bed. Private large balcony with patio chairs and table. Stateroom Amenities : AC Current. Two porthole windows. Interior with Picture Window Obstructed Views Cabin type: inside 4J Two twin beds convert to king , one upper pullman and single sofa bed. Picture window with obstructed views. Interior Stateroom Cabin type: inside 4A Two twin beds convert to king. Floor-to- ceiling windows. Picture window. Sofa, armchairs and coffee table. Walk-in dressing area with vanity table and chair. Stateroom Amenities : Priority check-in during embarkation. Learn more. Any international shipping is paid in part to Pitney Bowes Inc. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab International shipping and import charges paid to Pitney Bowes Inc. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab Any international shipping and import charges are paid in part to Pitney Bowes Inc. -

Cruise Ship Color Status | CDC 6/29/21, 11:11 AM

Cruise Ship Color Status | CDC 6/29/21, 11:11 AM COVID-19 IF YOU ARE FULLY VACCINATED Find new guidance for fully vaccinated people. If you are not vaccinated, !nd a vaccine. Cruise Ship Color Status Updated June 28, 2021 Print CDC is committed to helping cruise lines provide for the safety and well-being of their crew members while onboard cruise ships. CDC fully supports the e"orts of cruise ship operators to vaccinate their crew. CDC implemented the COVID-19 color-coding system for cruise ships to mitigate transmission of COVID-19 onboard. Onboard preventive measures are recommended or required based on ship color status. A cruise ship’s color status is determined based on the criteria below. All cruise ships operating in U.S. waters, or seeking to operate in U.S. waters, must comply with all of the requirements under the CDC Framework for Conditional Sailing Order (CSO) and Technical Instructions even when outside U.S. waters. The CSO was written as a phased approach toto taketake intointo accountaccount thethe evolvingevolving statestate ofof thethe COVID-19COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and worldwide. For an infographic on the phased approach, visit https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/pdf/CSO-Phased-Approach-Infographic-p.pdf.. Eligibility for Ship Color Status Ships are eligible for color status based on the following: • Established a COVID-19 complete and accurate COVID-19 response plan. - This does not mean ships are allowed to resume passenger operations, but rather that they have met CDC’s requirements to provide adequate health and safety protections for crew members. -

Printmgr File

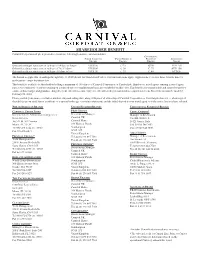

SHAREHOLDER BENEFIT Carnival Corporation & plc is pleased to extend the following benefit to our shareholders: CONTINENTAL NORTH AMERICAN UNITED KINGDOM EUROPEAN AUSTRALIAN BRANDS BRANDS BRANDS BRAND Onboard credit per stateroom on sailings of 14 days or longer US $250 £125 €200 AUD 250 Onboard credit per stateroom on sailings of 7 to 13 days+ US $100 £ 50 € 75 AUD 100 Onboard credit per stateroom on sailings of 6 days or less US $ 50 £ 25 € 40 AUD 50 The benefit is applicable on sailings through July 31, 2010 aboard the brands listed below. Certain restrictions apply. Applications to receive these benefits must be made prior to cruise departure date. This benefit is available to shareholders holding a minimum of 100 shares of Carnival Corporation or Carnival plc. Employees, travel agents cruising at travel agent rates, tour conductors or anyone cruising on a reduced-rate or complimentary basis are excluded from this offer. This benefit is not transferable and cannot be used for casino credits/charges and gratuities charged to your onboard account. Only one onboard credit per shareholder-occupied stateroom. Reservations must be made by February 28, 2010. Please provide your name, reservation number, ship and sailing date, along with proof of ownership of Carnival Corporation or Carnival plc shares (i.e., photocopy of shareholder proxy card, shares certificate or a current brokerage or nominee statement) and the initial deposit to your travel agent or to the cruise line you have selected. NORTH AMERICAN BRANDS UNITED KINGDOM BRANDS CONTINENTAL EUROPEAN BRANDS CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES P&O CRUISES COSTA CRUISES* Guest Solutions Administration Supervisor Reservations Manager Manager of Reservation Guest Services Carnival UK Via XII Ottobre, 2 3655 N.W. -

79667 FCCA Profiles

TableTable ofofContentsContents CARNIVAL CORPORATION Mark M. Kammerer, V.P., Worldwide Cruise Marketing . .43 Micky Arison, Chairman & CEO (FCCA Chairman) . .14 Stein Kruse, Senior V.P., Fleet Operations . .43 Giora Israel, V.P., Strategic Planning . .14 A. Kirk Lanterman, Chairman & CEO . .43 Francisco Nolla, V.P., Port Development . .15 Gregory J. MacGarva, Director, Procurement . .44 Matthew T. Sams, V.P., Caribbean Relations . .44 CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES Roger Blum, V.P., Cruise Programming . .15 NORWEGIAN CRUISE LINE Gordon Buck, Director, Port Operations. .16 Capt. Kaare Bakke, V.P. of Port Operations . .48 Amilicar “Mico” Cascais, Director, Tour Operations . .16 Sharon Dammar, Purchasing Manager, Food & Beverages . .48 Brendan Corrigan, Senior V.P., Cruise Operations . .16 Alvin Dennis, V.P., Purchasing & Logistics Bob Dickinson, President . .16 (FCCA Purchasing Committee Chairman) . .48 Vicki L. Freed, Senior V.P. of Sales & Marketing . .17 Colin Murphy, V.P, Land & Air Services . .48 Joe Lavi, Staff V.P. of Purchasing . .18 Joanne Salzedo, Manager, International Shore Programs . .49 David Mizer, V.P., Strategic Sourcing Global Source . .18 Andrew Stuart, Senior V.P., Marketing & Sales . .49 Francesco Morrello, Director, Port Development Group . .18 Colin Veitch, President & CEO . .49 Gardiner Nealon, Manager, Port Logistics . .19 Mary Sloan, Director, Risk Management . .19 PRINCESS CRUISES Terry L. Thornton, V.P., Marketing Planning Deanna Austin, V.P., Yield Management . .52 (FCCA Marketing Committee Chairman) . .19 Dean Brown, Executive V.P., Customer Service Capt. Domenico Tringale, V.P., Marine & Port Operations . .19 & Sales; Chairman & CEO of Princess Tours . .52 Jeffrey Danis, V.P., Global Purchasing & Logistics . .52 CELEBRITY CRUISES Graham Davis, Manager, Shore Operations, Caribbean and Atlantic . -

Statewide Cruise Perspective

Florida’s Cruise Industry Statewide Perspective Executive Summary Florida has long held the distinction of being the number one U.S. cruise state, home to the top three cruise ports in the world — PortMiami, Port Everglades and Port Canaveral. However, Florida is in danger of losing this economically favorable status, with potential redeployment of the increasingly large floating assets of the cruise industry to other markets. Great future opportunity clearly exists, as the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA) continues to cite the cruise industry as the fastest-growing segment of the travel industry and notes that because only approximately 24 percent of U.S. adults have ever Cruise ships at PortMiami taken a cruise vacation, there remains an enormous untapped market. Introduction As detailed in this report, the cruise industry is Recognizing the importance of the cruise industry continuing to bring new ships into service on a global to the present and future economic prosperity basis, with a focus upon larger vessels, those capable of the state of Florida, the Florida Department of of carrying as many as 4,000 or more passengers Transportation commissioned this report to furnish a per sailing – twice the capacities of the vessels statewide perspective. introduced as the first “megaships” two decades ago. The report is designed to help provide a framework While the larger vessels provide opportunities for for actions—including engagement with cruise lines greater economic impacts, they may not consistently and cruise ports and appropriate deployment of fiscal be deployed at Florida ports if the appropriate resources—to ensure that Florida retains and enhances infrastructure is not in place. -

DOUBLE ORDER from CARNIVAL Trieste, 19Th

FINCANTIERI: DOUBLE ORDER FROM CARNIVAL Trieste, 19th December 2014 - Fincantieri has been awarded an order by Carnival Corporation & plc for the construction of two new cruise ships for Carnival Cruise Line and Holland America Line. Both will be sisters ships respectively to “Carnival Vista” and “Koningsdam”, currently under construction at Fincantieri shipyards. The Carnival Cruise Line ship, the 26th unit in line’s fleet, with a gross tonnage of 133,500 tonnes, will have capacity for 3,954 passengers and will enter service in the spring 2018. The Holland America Line ship, a second Pinnacle class unit, will have a gross tonnage of 99,500 tonnes and accommodation for 2,650 passengers and will be delivered in autumn 2018. Giuseppe Bono, CEO of Fincantieri, stated: “To have been once more chosen for such an important order is the best recognition for our skills. This is an extremely important sign, especially if we consider the shipbuilding industry’s present period of evolution, both in Europe and Asia. Today Fincantieri can count on a solid order book, without equal in terms of diversification and quality of the product, which is a testament to our leadership in the cruise ship business sector. This position has been solidified over the years also thanks to our relationship with Carnival, a partnership which has allowed us to grow and which is now strengthened by our recent agreement involving the Chinese market and by today’s orders. We are hopeful that many others will follow in the future”. “These beautiful new ships on order from Fincantieri signify our ongoing commitment to provide the best possible guest experience across our industry-leading brands," said Arnold Donald, President & CEO of Carnival Corporation. -

Cruise Ship Preliminary Design: the Influence of Design Eaturf Es on Profitability

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-18-2014 Cruise Ship Preliminary Design: The Influence of Design eaturF es on Profitability Justin Epstein University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Business Commons, Ocean Engineering Commons, Other Engineering Commons, and the Other Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Epstein, Justin, "Cruise Ship Preliminary Design: The Influence of Design eaturF es on Profitability" (2014). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1914. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1914 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cruise Ship Preliminary Design: The Influence of Design Features on Profitability Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering Concentration in Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering by Justin Epstein B.S. -

Slavery Statement

This statement, pursuant to Australia’s Modern Slavery Act 2018 and the United Kingdom’s Modern Slavery Act 2015, sets out the actions taken by Carnival Corporation and plc to address the risks of modern slavery and human trafficking in our operations and in our supply chains over the financial year ending 30 November 2020 (“the reporting period”). Carnival Plc’s structure, operations, and supply chains Structure Carnival plc, together with Carnival Corporation, operate a dual listed company, whereby the businesses of Carnival Corporation and Carnival plc are combined through a number of contracts and through provisions in Carnival Corporation’s Articles of Incorporation and By-Laws and Carnival plc’s Articles of Association. The two companies operate as if they are a single economic enterprise with a single senior executive management team and identical Boards of Directors, but each has retained its separate legal identity. Carnival Corporation and Carnival plc are both public companies with separate stock exchange listings and their own shareholders. Carnival Corporation was incorporated in Panama in 1974 and Carnival plc was incorporated in England and Wales in 2000. More information on the structure of Carnival Corporation and Carnival plc, including a full list of Carnival Corporation and Carnival plc’s subsidiaries, can be found in our Annual Report (Form 10-K) available here on our website. Carnival Corporat ion and Carnival plc are referred to collectively throughout this statement as “our”, “we” and “us”. For the purposes of this statement, the reporting entity is Carnival plc. However, given the structure of our business, many of the policies, procedures and initiatives are applied across both Carnival plc and Carnival Corporation. -

Carnival Consolidated Complaint

Case 1:20-cv-22202-KMM Document 52 Entered on FLSD Docket 12/17/2020 Page 1 of 116 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA Master File No. 1:20-cv-22202-KMM IN RE CARNIVAL CORP. CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION SECURITIES LITIGATION COMPLAINT [CORRECTED] CLASS ACTION DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Hon. K. Michael Moore Case 1:20-cv-22202-KMM Document 52 Entered on FLSD Docket 12/17/2020 Page 2 of 116 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 2 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ....................................................................................... 10 III. PARTIES .......................................................................................................................... 11 A. Lead Plaintiffs ....................................................................................................... 11 B. Named Plaintiff ..................................................................................................... 11 C. Defendants ............................................................................................................ 11 IV. DEFENDANTS’ FRAUDULENT SCHEME .................................................................. 13 A. Background On Carnival ...................................................................................... 13 B. Throughout Its History, Carnival Has Touted Its Commitment To Ensuring Passengers’ Safety And Security ..........................................................