UNDISCLOSED, the State V. Adnan Syed Episode 8 - Ping August 03, 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S.Tramp Et Al. / an Architecture of a Distributed Semantic Social Network

Semantic Web 1 (2012) 1–16 1 IOS Press An Architecture of a Distributed Semantic Social Network Sebastian Tramp a;∗, Philipp Frischmuth a, Timofey Ermilov a, Saeedeh Shekarpour a and Sören Auer a a Universität Leipzig, Institut für Informatik, AKSW, Postfach 100920, D-04009 Leipzig, Germany E-mail: {lastname}@informatik.uni-leipzig.de Abstract. Online social networking has become one of the most popular services on the Web. However, current social networks are like walled gardens in which users do not have full control over their data, are bound to specific usage terms of the social network operator and suffer from a lock-in effect due to the lack of interoperability and standards compliance between social networks. In this paper we propose an architecture for an open, distributed social network, which is built solely on Semantic Web standards and emerging best practices. Our architecture combines vocabularies and protocols such as WebID, FOAF, Se- mantic Pingback and PubSubHubbub into a coherent distributed semantic social network, which is capable to provide all crucial functionalities known from centralized social networks. We present our reference implementation, which utilizes the OntoWiki application framework and take this framework as the basis for an extensive evaluation. Our results show that a distributed social network is feasible, while it also avoids the limitations of centralized solutions. Keywords: Semantic Social Web, Architecture, Evaluation, Distributed Social Networks, WebID, Semantic Pingback 1. Introduction platform or information will diverge. Since there are only a few large social networking players, the Web Online social networking has become one of the also loses its distributed nature. -

Usenet News HOWTO

Usenet News HOWTO Shuvam Misra (usenet at starcomsoftware dot com) Revision History Revision 2.1 2002−08−20 Revised by: sm New sections on Security and Software History, lots of other small additions and cleanup Revision 2.0 2002−07−30 Revised by: sm Rewritten by new authors at Starcom Software Revision 1.4 1995−11−29 Revised by: vs Original document; authored by Vince Skahan. Usenet News HOWTO Table of Contents 1. What is the Usenet?........................................................................................................................................1 1.1. Discussion groups.............................................................................................................................1 1.2. How it works, loosely speaking........................................................................................................1 1.3. About sizes, volumes, and so on.......................................................................................................2 2. Principles of Operation...................................................................................................................................4 2.1. Newsgroups and articles...................................................................................................................4 2.2. Of readers and servers.......................................................................................................................6 2.3. Newsfeeds.........................................................................................................................................6 -

Blogging for Engines

BLOGGING FOR ENGINES Blogs under the Influence of Software-Engine Relations Name: Anne Helmond Student number: 0449458 E-mail: [email protected] Blog: http://www.annehelmond.nl Date: January 28, 2008 Supervisor: Geert Lovink Secondary reader: Richard Rogers Institution: University of Amsterdam Department: Media Studies (New Media) Keywords Blog Software, Blog Engines, Blogosphere, Software Studies, WordPress Summary This thesis proposes to add the study of software-engine relations to the emerging field of software studies, which may open up a new avenue in the field by accounting for the increasing entanglement of the engines with software thus further shaping the field. The increasingly symbiotic relationship between the blogger, blog software and blog engines needs to be addressed in order to be able to describe a current account of blogging. The daily blogging routine shows that it is undesirable to exclude the engines from research on the phenomenon of blogs. The practice of blogging cannot be isolated from the software blogs are created with and the engines that index blogs and construct a searchable blogosphere. The software-engine relations should be studied together as they are co-constructed. In order to describe the software-engine relations the most prevailing standalone blog software, WordPress, has been used for a period of over seventeen months. By looking into the underlying standards and protocols of the canonical features of the blog it becomes clear how the blog software disperses and syndicates the blog and connects it to the engines. Blog standards have also enable the engines to construct a blogosphere in which the bloggers are subject to a software-engine regime. -

Structured Feedback

Structured Feedback A Distributed Protocol for Feedback and Patches on the Web of Data ∗ Natanael Arndt Kurt Junghanns Roy Meissner Philipp Frischmuth Norman Radtke Marvin Frommhold Michael Martin Agile Knowledge Engineering and Semantic Web (AKSW) Institute of Computer Science Leipzig University Augustusplatz 10 04109 Leipzig, Germany {arndt|kjunghanns|meissner|frischmuth|radtke|frommhold|martin}@informatik.uni-leipzig.de ABSTRACT through web resources. With the advent of discussion fo- The World Wide Web is an infrastructure to publish and re- rums, blogs, short message services like Twitter and on- trieve information through web resources. It evolved from a line social networks like Facebook, the web evolved towards static Web 1.0 to a multimodal and interactive communica- the Web 2.0. With the Semantic Web resp. Web of Data, tion and information space which is used to collaboratively the web is now evolving towards a Web 3.0 consisting of contribute and discuss web resources, which is better known structured and linked data resources (Linked Data, cf. [3]). as Web 2.0. The evolution into a Semantic Web (Web 3.0) Even though Web 2.0 services can be transformed to pro- proceeds. One of its remarkable advantages is the decentral- vide Linked Data [7], there is a need for services to collabo- ized and interlinked data composition. Hence, in contrast ratively interact with meaningful data and enable (Linked) to its data distribution, workflows and technologies for de- Data Services to be integrated into the existing social web centralized collaborative contribution are missing. In this stack. Currently the Distributed Semantic Social Network paper we propose the Structured Feedback protocol as an (DSSN, section 3.1 and [18]) is available as a framework interactive addition to the Web of Data. -

Cobra: Content-Based Filtering and Aggregation of Blogs and RSS Feeds

Cobra: Content-based Filtering and Aggregation of Blogs and RSS Feeds Ian Rose, Rohan Murty, Peter Pietzuch, Jonathan Ledlie, Mema Roussopoulos, and Matt Welsh School of Engineering and Applied Sciences { Harvard University } ianrose,rohan,prp,jonathan,mema,mdw @eecs.harvard.edu Abstract suited to tracking and indexing such rapidly-changing Blogs and RSS feeds are becoming increasingly popular. The content. Many users make use of RSS feeds, which in blogging site LiveJournal has over 11 million user accounts, conjunction with an appropriate reader, allow users to re- and according to one report, over 1.6 million postings are made to blogs every day. The “Blogosphere” is a new hotbed of ceive rapid updates to sites of interest. However, existing Internet-based media that represents a shift from mostly static RSS protocols require each client to periodically poll to content to dynamic, continuously-updated discussions. The receive new updates. In addition, a conventional RSS problem is that finding and tracking blogs with interesting con- tent is an extremely cumbersome process. feed only covers an individual site, such as a blog. The In this paper, we present Cobra (Content-Based RSS Ag- current approach used by many users is to rely on RSS gregator), a system that crawls, filters, and aggregates vast aggregators, such as SharpReader and FeedDemon, that numbers of RSS feeds, delivering to each user a personalized collect stories from multiple sites along thematic lines feed based on their interests. Cobra consists of a three-tiered (e.g., news or sports). network of crawlers that scan web feeds, filters that match Our vision is to provide users with the ability to per- crawled articles to user subscriptions, and reflectors that pro- form content-based filtering and aggregation across mil- vide recently-matching articles on each subscription as an RSS feed, which can be browsed using a standard RSS reader. -

IBM I: TCP/IP Troubleshooting • a Default Route (*DFTROUTE) Allows Packets to Travel to Hosts That Are Not Directly Connected to Your Network

IBM i Version 7.2 Networking TCP/IP troubleshooting IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 71. This document may contain references to Licensed Internal Code. Licensed Internal Code is Machine Code and is licensed to you under the terms of the IBM License Agreement for Machine Code. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 1997, 2013. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents TCP/IP troubleshooting......................................................................................... 1 PDF file for TCP/IP troubleshooting............................................................................................................ 1 Troubleshooting tools and techniques........................................................................................................1 Tools to verify your network structure...................................................................................................1 Tools for tracing data and jobs.............................................................................................................15 Troubleshooting tips............................................................................................................................ 31 Advanced troubleshooting tools..........................................................................................................66 Troubleshooting problems related -

International Journal of Current Research In

Int.J.Curr.Res.Aca.Rev.2017; 5(7): 121-129 International Journal of Current Research and Academic Review ISSN: 2347-3215 (Online) ҉҉ Volume 5 ҉҉ Number 7 (July-2017) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcrar.com doi: https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcrar.2017.507.016 RSS Feed and RDF Web Syndication Tools for Web Developers S. Machendranath1* and Umesha Naik2 1University Librarian I/c. University of Agricultural Sciences, Raichur, Karnataka, India 2Department of Library and Information Science, Mangalore University, Mangalagangothri, Mangalore - 574 199, Karnataka, India *Corresponding author Abstract Article Info Web feeds allows software programs to check for updates published on a website, RDF Accepted: 02 June 2017 Site Summary or Rich Site Summary or Really Simple Syndication (RSS) is a tool that Available Online: 20 July 2017 allows organizations to deliver news to a desktop computer or other Internet device. This article mainly focuses on the features and functions of RSS feeds, how it will Keywords helpful in the web master up to date the information. Some organizations or Libraries offer several RSS feeds for use in an RSS reader or RSS enabled Web browser. In the RSS, Atoms, RDF, Web present scenario number of web developers set up these tools for subscribing to RSS Syndication, Content Syndication, feeds, users can easily stay up-to-date with areas of the Library's site that are of Web Content Syndication, Web interest. In this article author also highlights the different standard tools and its Developer availability and functions of Web syndication, RSS, RDF and Atoms. Introduction updates from favorite websites or to aggregate data from many sites. -

Social Bookmarking Tools As Facilitators of Learning and Research Collaborative Processes: the Diigo Case

Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects Volume 6, 2010 Social Bookmarking Tools as Facilitators of Learning and Research Collaborative Processes: The Diigo Case Enrique Estellés Esther del Moral Department of Mathematics, Department of Education Physics and Computation, Science, CEU-Cardenal Herrera University, University of Oviedo, Spain Valencia, Spain [email protected] [email protected] Fernando González Department of Management, Technical University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain [email protected] Abstract Web 2.0 has created new applications with remarkable socializing nuance, such as the SBS (So- cial Bookmarking Systems). Rather than focusing on the relationship between users, the SBS provide users with the necessary tools to manage and use information that can later be shared. This article presents a description, analysis, and comparison of different SBS, which are catego- rized as web applications that help to store, classify, organize, describe, and share multi-format information through links to interesting web sites, blogs, pictures, wikis, videos and podcasts. Also emphasized are the advantages for learning and collaborative research that SBS produce. In this paper, Diigo will be specifically studied for its contribution as a metacognitive tool. Diigo shows the way each user learns, thinks, and develops the knowledge that was obtained from the information previously selected, organized, and categorized. Thus, the information becomes high- ly valuable, and knowledge is cooperatively built. This knowledge induces collaborative learning and research, since the tags that describe marked resources are shared between users. Conse- quently, they become meaningful learning resources that provide a social dimension to both learning and online research processes. Material published as part of this publication, either on-line or Keywords: Social Bookmarking Sys- in print, is copyrighted by the Informing Science Institute. -

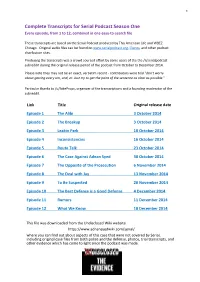

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made. -

Diffusion 6.6 User Guide Contents

Diffusion 6.6 User Guide Contents List of Figures..............................................................................................10 List of Tables............................................................................................... 12 Part I: Welcome.......................................................................... 15 Introducing Diffusion................................................................................................. 16 Introducing topics and data................................................................................................ 16 Introducing sessions.............................................................................................................20 What's new in Diffusion 6.6?...................................................................................... 23 Part II: Quick Start Guide............................................................ 26 Part III: Design Guide.................................................................. 27 Support.....................................................................................................................28 System requirements for the Diffusion server....................................................................28 Platform support for the Diffusion API libraries.................................................................31 Feature support in the Diffusion API...................................................................................33 License types.........................................................................................................................38 -

BLOGS for SMALL BUSINESS WHAT’S INSIDE What Is a Blog?

BLOGS FOR SMALL BUSINESS WHAT’S INSIDE What is a Blog? ...................................1 Blogs are a form of social media that provide businesses with What can a blog achieve the opportunity to speak directly to the market and give readers for your business? ..........................1 a chance to respond and to share posts with others thereby Getting Started ....................................2 creating a conversation among many like-minded individuals. 1. Research and Planning .............2 This booklet focuses on the opportunities, benefits and how to’s 2. Understanding Best Practices ..4 of creating a successful blog to market your business. Nuts & Bolts .......................................5 1. Designing Your Blog ..................5 2. Developing a Content Plan What is a Blog? and Timeline ..............................5 A blog is a type of website maintained by an individual or business where 3. Use of Photography and Video ...6 commentary, news, articles of interest and graphics can be posted. A blog 4. Marketing Your Blog ..................6 differs from a traditional website in that it is usually updated more frequently 5. Advertising .................................7 and provides mechanisms for readers to leave comments and share posts 6. Integrating Social Media with others. Applications ...............................8 7. Importance of Keeping With the right content and approach toward your blog and its readers you can a Blog Current............................9 personalize your company and build a solid reputation and foundation online. If you produce content regularly and consistently review and respond to 8. How Feeds Work ......................10 comments, you can build a loyal readership and create a strong interaction 9. Plugins, Widgets .....................10 with potential and existing customers. 10. SEO Tagging ..........................12 11. -

Trackback Spam: Abuse and Prevention

TrackBack Spam: Abuse and Prevention Elie Bursztein∗ Peifung E. Lam* John C. Mitchell* Stanford University Stanford University Stanford University [email protected] pfl[email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT The TrackBack mechanism [3] is used to automatically insert Contemporary blogs receive comments and TrackBacks, which cross-references between blogs. A new blog post citing an result in cross-references between blogs. We conducted a lon- older one on a different blog can use the TrackBack interface gitudinal study of TrackBack spam, collecting and analyzing to insert a link in the older post automatically. TrackBacks almost 10 million samples from a massive spam campaign are an intrinsic part of the blogosphere, and a key ingredient over a one-year period. Unlike common delivery of email used in blog ranking (Sec. 2). Because TrackBacks are auto- spam, the spammers did not use bots, but took advantage of mated, CAPTCHA and registration requirements cannot be an official Chinese site as a relay. Based on our analysis of used to protect the TrackBack mechanism. Over the last few TrackBack misuse found in the wild, we propose an authenti- years, abuse of the TrackBack mechanism has emerged as a cated TrackBack mechanism that defends against TrackBack key problem, with some attacks causing sites to disable this spam even if attackers use a very large number of different feature [5]. So far, however, very little research has been con- source addresses and generate unique URLs for each Track- ducted on how TrackBack spam is carried out in the wild. To Back blog. better understand how attackers currently abuse the Track- Back mechanism and to help design better defenses in the future, we instrumented an operating blog site and collected 1.