Constructing Straightness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trailblazer GNICUDORTNI Trailblazer Trailblazer Stfieneb & Skrep Rof Ruo Srebircsbus

The Sentinel The Sentinel The Sentinel Stress Free - Sedation Dentistr y September 14 - 20, 2019 tvweekSeptember 14tv - 20, 2019 week tvweekSeptember 14 - 20,George 2019 Blashford,Blashford, DMD 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com Trailblazer INTRODUCING Trailblazer Trailblazer Benefits & Perks For Our Subscribers Introducing News+ Membership, a program for our Lilly Singh hosts “A Little subscribers, dedicated to ooering perks and benefits taht era Lilly Singh hosts “A Little Late With Lilly Singh” only available to you as a member. News+ Members will Late With Lilly Singh” continue to get the stories and information that makes a Lilly Singh hosts “A Little dioerence to them, plus more coupons, ooers, and perks taht Late With Lilly Singh” only you as a member nac .teg COVER STORY / CABLE GUIDE ...............................................2 COVER STORY / CABLE GUIDE ...............................................2 SUDOKUGiveaways / VIDEO RSharingELEASES ..................................................Events Classifieds Deals Plus More8 SCUDOKUROSSWORD / VIDEO .................................................................... RELEASES ..................................................83 CROSSWORD ....................................................................3 WORD SEARCH...............................................................16 CWOVERSPORTSORD STORY S...........................................................................EARCH / C...............................................................ABLE -

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-Century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London P

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London PhD January 2015 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Philippa Burt 2 Acknowledgements This thesis benefitted from the help, support and advice of a great number of people. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Maria Shevtsova for her tireless encouragement, support, faith, humour and wise counsel. Words cannot begin to express the depth of my gratitude to her. She has shaped my view of the theatre and my view of the world, and she has shown me the importance of maintaining one’s integrity at all costs. She has been an indispensable and inspirational guide throughout this process, and I am truly honoured to have her as a mentor, walking by my side on my journey into academia. The archival research at the centre of this thesis was made possible by the assistance, co-operation and generosity of staff at several libraries and institutions, including the V&A Archive at Blythe House, the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Archives in Kew, the Fabian Archives at the London School of Economics, the National Theatre Archive and the Clive Barker Archive at Rose Bruford College. Dale Stinchcomb and Michael Gilmore were particularly helpful in providing me with remote access to invaluable material held at the Houghton Library, Harvard and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, respectively. -

Green Gets Finger for Film 'T

&6 THE 0 RIO N • APR I L 2 5, 200 1 I ! " , " ..~ Green gets finger for film 't , ~ DANA BUCHANAN ' I:i CONTHIIIIJTING WlllTlJ1l This is a warning: If you are not a huge fan of Tom Green and his MTV show, and if you have not been waiting to see him in all his complete, uncensored grotesque glory, then do not sec "Freddy Got Fingered." Tom Green wrote, directed and stars in "Freddy Got Fingered," and his signature brand of comedy is slathered all over this mm. Green plays Gord Brody, a 28-year old slacker who finally leaves home (to his parents elation) to attempt to become a professional animator, only to return home disappointed. Instantly the antics begin in that strange unexplainable Tom Green way. Gord just docs weird (uncomfortably weird) stuff without much rhyme or reason. If you have never before seen, or wanted to sec, someone fondle animal genitalia (horse and elephant respectively), then you might be in for a shock, to say the least. The story line of Gord wanting to be a professional animator docs seem to make perfect sense. Gord is a child in a semi adult's body, and drawing cartoons fits the character perfectly. Gord goes to Los Angeles to try to sell his work by breaking into the office of an animation executive (Anthony Michael Hall). This scene is relatively funny as Gord confounds security with his "weirdness" (for lack of a better word) and manages to get to the office of the head honcho. Then of course, there is a lot of Green's usual bizarre physical comedy, which makes one wonder why the exec hasn't called security yet. -

Chicago's Goodman Theatres the Transition from a Division of the Art Institute of Chicago to an Independent Regional Theatre

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. January 5, 2015 to Sun. January 11, 2015 Monday January 5, 2015 Tuesday January 6, 2015

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. January 5, 2015 to Sun. January 11, 2015 Monday January 5, 2015 5:30 PM ET / 2:30 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Gene Simmons Family Jewels Baltic Coasts Face Your Demons - While on tour in Amsterdam, Gene and Shannon spend some quality time The Bird Route - Every spring and autumn, thousands of migrating birds over the Western with a young fan writing a school report. Pomeranian bodden landscape deliver one of the most breathtaking nature spectacles. 6:30 PM ET / 3:30 PM PT 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Gene Simmons Family Jewels Smart Travels Europe What Happens In Vegas... - Gene and Shannon get invited to the premiere of the new Cirque du Out of Rome - We leave the eternal city behind by way of the famous Apian Way to explore the Soleil show “Viva Elvis” in Las Vegas. environs of Rome. First it’s the majesty of Emperor Hadrian’s villa and lakes of the Alban Hills. Next, it’s south to the ancient seaport of Ostia, Rome’s Pompeii. Along the way we sample olive 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT oil, stop at the ancient’s favorite beach and visit a medieval hilltop town. Our own five star villa Gene Simmons Family Jewels is a retreat fit for an emperor. God Of Thund - An exhausted Shannon reaches her limit with Gene’s snoring and sends him packing to a sleep doctor. 9:30 AM ET / 6:30 AM PT The Big Interview Premiere Alan Alda - Hollywood’s Mr. -

Peach Norman's Orman's, Rca Victor

ym MX-y FRIDAY, JLU<5tJS5 21, 10«4 The AvHrifFDailjr Net Preea R ub |RimrIi»0ter Sit^nitq^ Hrralb --- ------------------ ; ad U. S. 1 ‘ , Woe -Omt eftok'RnCM V' : • A ufuft 15, IBM OhmRy «kla Marilyn OourU bulldinr of aosilitg. Big lots ara TlM M^ncMatar Rotary Club and breed st^isnMvo feouia- ■Ight with park M flt i more than 100 units at Adams lahi aai driola. I ^ T o w n will have an open meeting Apartment Building Value and Olcott 8ts. Such a build Renos the only wsqr So psodooe 13,764 Tueaday at 6:30 pm. at the ing requires so large an in InexpaBstve liousihg Is to bidld ■Ma, Boattond Muioheataf Oonntiy Club. r «C tha Audit warnwr tomomw. vestment that It may not be aparisnent typo rental units s i OteoQlattaa IMpMt A OMMtojTO_£Kr. In Fiscal Year Sets Record dufdloated for some time. that wfll aooonanodate mors Mmchmstor~—A City o f Villdge Charm "iBHHeldt Ohsan^ 44 The Junior Century Club of In addition, the Town Plan peoplo on the sanM amount of Dr, taft Wtyik F. Mancheater, Inc., will have Ita The dollar value of apartmentfment building last year, the ning Commission (TPC) is PRICE SEVEN C E N T t _ HD o f Mr. and annual Summer Ldwn Party drafting new zoning regulations MANCHESTER, CONN, SATURDAY, AUGUST 22; 1964 (OaeaMled Adverttatoa *) Friday, Aug. 38 at 8 p.m. on the construction in Manchester hit total value of new eenstruction All together the facts kuH- TOL. LXXXm , NO. 276 (TEN PAGES^TV SECTION) Ml*. -

DISNEYLAND Grand Opening on 7/17/1955 the Happiest Place on Earth Wasn't Anything of the Sort for 13 Months of Pandemic Closure

Monday, July 19, 2021 | No. 177 Film Flashback…DISNEYLAND Grand Opening on 7/17/1955 The Happiest Place on Earth wasn't anything of the sort for 13 months of pandemic closure. But, happily, Disneyland began coming back to life in late April and by June 15 wasn't facing any capacity restrictions. Now it's celebrating the 66th anniversary of its Grand Opening July 17, 1955. To help finance Disneyland's construction in Anaheim, Calif., which began July 16, 1954, Walt Disney struck a deal with the then fledgling ABC-TV Network to produce the legendary DISNEYLAND series. For helping Walt raise the $17M he needed -- about $135M today -- ABC also got the right to broadcast the opening day events. Originally, July 17 was just an International Press Preview and July 18 was to be the official launch. But July 17's been remembered over the years as the Big Day thanks to ABC's live coverage -- despite things not having gone well with the show hosted by Walt's Hollywood pals Art Linkletter, Bob Cummings & Ronald Reagan. Live TV was in its infancy then and the miles of camera cables it used had people tripping all over the park. In Frontierland, a camera caught Cummings kissing a dancer. Walt was reading a plaque in Tomorrowland on camera when a technician started talking to him, causing Walt to stop and start again from the beginning. Over in Fantasyland, Linkletter sent the coverage back to Cummings on a pirate ship, but Bob wasn't ready, so he sent it right back to Art, who no longer had his microphone. -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

The Birth of Haptic Cinema

The Birth of Haptic Cinema An Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Panhavuth Lau Jordan Stoessel Date: May 21, 2020 Advisor: Brian Moriarty IMGD Professor of Practice Abstract This project examines the history of The Tingler (1959), the first motion picture to incorporate haptic (tactile) sensations. It surveys the career of its director, William Castle, a legendary Hollywood huckster famous for his use of gimmicks to attract audiences to his low- budget horror films. Our particular focus is Percepto!, the simple but effective gimmick created for The Tingler to deliver physical “shocks” to viewers. The operation, deployment and promotion of Percepto! are explored in detail, based on recently-discovered documents provided to exhibitors by Columbia Pictures, the film’s distributor. We conclude with a proposal for a method of recreating Percepto! for contemporary audiences using Web technologies and smartphones. i Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... i Contents ........................................................................................................................................ ii 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 2. William Castle .......................................................................................................................... -

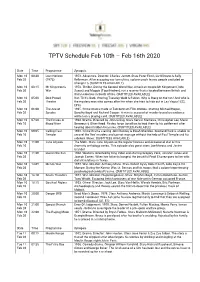

TPTV Schedule Feb 10Th – Feb 16Th 2020

TPTV Schedule Feb 10th – Feb 16th 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 10 00:30 Lost Horizon 1973. Adventure. Director: Charles Jarrott. Stars Peter Finch, Liv Ullmann & Sally Feb 20 (1973) Kellerman. After escaping war torn china, a plane crash leaves people secluded on Shangri-La. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 03:15 Mr Kingstreet's 1972. Thriller. During the Second World War, American couple Mr Kingstreet (John Feb 20 War Saxon) and Maggie (Tippi Hedren), run a reserve that is located between British and Italian colonies in South Africa. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 05:00 Dick Powell Run 'Til It's Dark. Starring Tuesday Weld & Fabian. Why is Stacy on the run? And who is Feb 20 Theatre the mystery man who comes after her when she tries to hide out in Las Vegas? (S2, EP3) Mon 10 06:00 The Ace of 1935. Crime drama made at Twickenham Film Studios. Starring Michael Hogan, Feb 20 Spades Dorothy Boyd and Richard Cooper. A man is accused of murder based on evidence written on a playing card. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 07:20 The Pirates of 1962. Drama. Directed by John Gilling. Stars Kerwin Mathews, Christopher Lee, Marie Feb 20 Blood River Devereux & Oliver Reed. Pirates force Jonathon to lead them to his settlement after hearing about hidden treasures. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 09:05 Calling Paul 1948. Crime Drama starring John Bentley & Dinah Sheridan. Scotland Yard is unable to Feb 20 Temple unravel the 'Rex' murders and cannot manage without the help of Paul Temple and his sidekick 'Steve'. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 11:00 June Allyson The Moth. -

El Fashion Film Como Máximo Exponente De Branded Content

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN TESIS DOCTORAL El fashion film como máximo exponente de branded content MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Carla Rogel del Hoyo Directora María del Marcos Molano Madrid © Carla Rogel del Hoyo, 2021 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN TESIS DOCTORAL El fashion film como máximo exponente de branded content MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Carla Rogel del Hoyo DIRECTORA María del Marcos Molano Universidad Complutense de Madrid Facultad de Ciencias de la Información Programa de Doctorado en Comunicación Audiovisual, Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas Departamento de Teorías y Análisis de la Comunicación El fashion film como máximo exponente de branded content Carla Rogel del Hoyo Directora: Dra. María del Mar Marcos Molano Madrid, 2020 A mi padre, para celebrar su jubilación, cuarenta años después de ver cómo preparaba la cátedra. Le deseo un retiro sosegado pero agitado, poético y cántabro, en compañía de su musa y madre mía. Felicidades. Esta tesis empezó en el corazón de Africa (Abidjan, Costa de Marfil) y terminó en medio de un estado de alarma provocado por una pandemia mundial. Tuve la suerte de empezar el recorrido siguiendo la pista que el profesor Merchán me dejó para llegar a la profesora Marcos, una impulsora de energía. En el camino, conté con la compañía supervisora del profesor Adhepeau y la ayuda amable de los profesores Encabo, Eguizábal, Cerrillo, Díaz Soloaga y Martínez Barreiro. Índice Resumen 1 Abstract 5 1. Introducción 10 1.1. Objeto de la investigación 15 1.2. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I I I 75-26,610

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.