Courts and Civil Justice in the Time of Covid [Forthcoming]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graduate Bulletin 2013-2015

Graduate Bulletin 2013-2015 Lehman College Bulletins (Catalogs) include information about admission requirements, continuation requirements, courses, degree requirements, and tuition and fees. The online Bulletins are updated periodically throughout the calendar year and provide the most current information for prospective students or for general review. Current students generally follow program requirements based on their date of matriculation, subject to changes in State requirements. All students must speak with a faculty adviser to confirm their requirements. Lehman College The City University of New York 250 Bedford Park Blvd. West Bronx, New York 10468 718-960-8000 www.lehman.edu Important Notice of Possible Changes The City University of New York reserves the right, because of changing conditions, to make modifications of any nature in the academic programs and requirements of the University and its constituent colleges without notice. Tuition and fees set forth in this publication are similarly subject to change by the Board of Trustees of the City University of New York. The University regrets any inconvenience this may cause. The responsibility for compliance with the regulations in each bulletin rests entirely with the student. The curricular requirements in this Bulletin apply to those students matriculated in the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 academic years. This Bulletin reflects policies, fees, curricula, and other information as of August 2013. Statement of Nondiscrimination Herbert H. Lehman College is an Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action Institution. The College does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national or ethnic origin, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, transgender, marital status, disability, genetic predisposition or carrier status, alienage or citizenship, military or veteran status, or status as victim of domestic violence in its student admissions, employment, access to programs, and administration of educational policies. -

Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty's Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism

Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center Occasional Papers Series Series Editor Tony Saich Deputy Editor Jessica Engelman The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. The Ford Foundation is a founding donor of the Center. Additional information about the Ash Center is available at ash.harvard.edu. This research paper is one in a series funded by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. The views expressed in the Ash Center Occasional Papers Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. This paper is copyrighted by the author(s). It cannot be reproduced or reused without permission. Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Letter from the Editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. -

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

FAKE NEWS!”: President Trump’S Campaign Against the Media on @Realdonaldtrump and Reactions to It on Twitter

“FAKE NEWS!”: President Trump’s Campaign Against the Media on @realdonaldtrump and Reactions To It on Twitter A PEORIA Project White Paper Michael Cornfield GWU Graduate School of Political Management [email protected] April 10, 2019 This report was made possible by a generous grant from William Madway. SUMMARY: This white paper examines President Trump’s campaign to fan distrust of the news media (Fox News excepted) through his tweeting of the phrase “Fake News (Media).” The report identifies and illustrates eight delegitimation techniques found in the twenty-five most retweeted Trump tweets containing that phrase between January 1, 2017 and August 31, 2018. The report also looks at direct responses and public reactions to those tweets, as found respectively on the comment thread at @realdonaldtrump and in random samples (N = 2500) of US computer-based tweets containing the term on the days in that time period of his most retweeted “Fake News” tweets. Along with the high percentage of retweets built into this search, the sample exhibits techniques and patterns of response which are identified and illustrated. The main findings: ● The term “fake news” emerged in public usage in October 2016 to describe hoaxes, rumors, and false alarms, primarily in connection with the Trump-Clinton presidential contest and its electoral result. ● President-elect Trump adopted the term, intensified it into “Fake News,” and directed it at “Fake News Media” starting in December 2016-January 2017. 1 ● Subsequently, the term has been used on Twitter largely in relation to Trump tweets that deploy it. In other words, “Fake News” rarely appears on Twitter referring to something other than what Trump is tweeting about. -

USA Recapture Mcconnell Cup

Co-ordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer (France) Issue: 12 Chief Editor: Mark Horton (England) Editors: Brent Manley (USA), Brian Senior (England) Layout Editor: George Hatzidakis (Greece) Photographer: Ron Tacchi (England) 28th August 2002 USA recapture McConnell Cup ATTENTION!!! All events begin at 10.00 Open and Women's Pairs 152 pairs play in the Open Pairs Semi-final. Approxi- mately 66 of these will qualify for the final, where about six more pairs are expected to drop in from the Rosenblum semi-finals and final to make a 72-pair final. An American team won the inaugural McConnell Cup 52 pairs play in the Women's Pairs Semi-final.We ex- contest in Albuquerque in 1994 and now eight years pect 21 to qualify for the final, with another 11 pairs later the trophy returns to its native soil.The all Amer- joining them from the McConnell semi-finals and final ican final saw Irina Levitina, Kerri Sanborn, Lynn Deas, to make a field of 32 pairs for the final. Beth Palmer, Randi Montin and Jill Meyers (pictured Both finals will be played over five sessions commenc- above) comfortably outscore Judi Radin, Shawn Quinn, ing on Thursday morning at 10.00 a.m. Mildred Breed, Rozanne Pollack, Hjordis Eythorsdottir and Valerie Westheimer. Seniors Pairs In the Power Rosenblum, after two scintillating semi fi- There are 72 pairs playing in the Seniors Pairs Qualify- nals, Lavazza meet Munawar in today's final. ing stage, of which 28 will go through to the final.This is a three-session event that starts at 10.00 a.m. -

C:\My Documents\Adobe\Boston Fall99

Presents They Had Their Beans Baked In Beantown Appeals at the 1999 Fall NABC Edited by Rich Colker ACBL Appeals Administrator Assistant Editor Linda Trent ACBL Appeals Manager CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................... iii The Expert Panel.................................................v Cases from San Antonio Tempo (Cases 1-24)...........................................1 Unauthorized Information (Cases 25-35)..........................93 Misinformation (Cases 35-49) .................................125 Claims (Cases 50-52)........................................177 Other (Case 53-56)..........................................187 Closing Remarks From the Expert Panelists..........................199 Closing Remarks From the Editor..................................203 Special Section: The WBF Code of Practice (for Appeals Committees) ....209 The Panel’s Director and Committee Ratings .........................215 NABC Appeals Committee .......................................216 Abbreviations used in this casebook: AI Authorized Information AWMPP Appeal Without Merit Penalty Point LA Logical Alternative MI Misinformation PP Procedural Penalty UI Unauthorized Information i ii FOREWORD We continue with our presentation of appeals from NABC tournaments. As always, our goal is to provide information and to foster change for the better in a manner that is entertaining, instructive and stimulating. The ACBL Board of Directors is testing a new appeals process at NABCs in 1999 and 2000 in which a Committee (called a Panel) comprised of pre-selected top Directors will hear appeals at NABCs from non-NABC+ events (including side games, regional events and restricted NABC events). Appeals from NABC+ events will continue to be heard by the National Appeals Committees (NAC). We will review both types of cases as we always have traditional Committee cases. Panelists were sent all cases and invited to comment on and rate each Director ruling and Panel/Committee decision. Not every panelist will comment on every case. -

Glossary of Bridge Terms

GLOSSARY OF BRIDGE TERMS Alert When your partner makes a conventional bid you must alert this to the opponents by knocking the table (or displaying the ‘Alert’ card if using bidding boxes). Auction Another term for the bidding. Avoidance An attempt to prevent a particular defender from regaining the lead. Balanced A hand containing no void, no singleton and not more than one Hand doubleton. Barrier When planning your opener's rebid, imagine a ‘barrier’ just above your first suit at the next level up. A new suit rebid below the barrier shows 12-15 points (occasionally 16 or 17 points after a 1 level response when opener doesn’t have enough for a jump shift). A new suit rebid above the barrier that isn’t a jump shift shows 16-19 points (also known as a reverse). Blocked A suit is blocked if there is a high card in the short hand that prevents the suit from being cashed. A player will often aim to unblock the suit. Break The way in which the defenders’ cards in a particular suit are divided between their two hands. For example, a 4-2 break indicates that with 6 cards in a suit missing, one defender has 4 cards of the suit and his partner has 2 cards. Also referred to as split. Cash Playing a card that is certain to win the trick. This card is known as a master. Clear a suit Knocking out the opponents’ last stopper in a suit, after which it will be possible to cash one’s tricks in the suit. -

Chip Company AMD Pursues Rival for $30 Billion Tie-Up

P2JW283000-5-A00100-17FFFF5178F ***** FRIDAY,OCTOBER 9, 2020 ~VOL. CCLXXVI NO.85 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 28425.51 À 122.05 0.4% NASDAQ 11420.98 À 0.5% STOXX 600 368.31 À 0.8% 10-YR. TREAS. (Re-opening) , yield 0.764% OIL $41.19 À $1.24 GOLD $1,888.60 À $5.00 EURO $1.1761 YEN 106.03 Conflicts in Russia’s Orbit Intensify, Upending Kremlin Plans Stimulus What’s News Talks Are On Again, Business&Finance But Deal MD is in advanced talks Ato buy Xilinx in adeal that could be valued at Is Elusive morethan $30 billion and mark the latest big tie-up in the rapidly consolidating Negotiations show semiconductor industry. A1 signs of life after AT&T’s WarnerMedia is Pelosi ties airline aid restructuring itsworkforce as it seeks to reducecostsby S to broad agreement as much as 20% as the pan- PRES demic drains income from TED BY KRISTINA PETERSON movie tickets, cable sub- CIA AND ALISON SIDER scriptions and TV ads. A1 SO AS MorganStanleysaid it is RE/ WASHINGTON—Demo- buying fund manager Eaton LU cratic and WhiteHouse negoti- TO Vancefor $7 billion, continu- atorsresumed discussions over ing the Wall Street firm’s N/PHO acoronavirus relief deal Thurs- shifttoward safer businesses YA day, but gavenoindication AR likemoney management. B1 AS they were closer to resolving GHD deep-seated disputes that led IBM plans itsbiggest- BA President Trump to end negoti- ever businessexit, spinning AM ationsearlier this week. off amajor part of itsinfor- HR FewonCapitol Hill were op- mation-technologyservices VA SHATTERED:Armenia accused Azerbaijan on Thursday of shelling ahistoric cathedral in the separatistterritory of Nagorno- timistic that Congressand the operations as the company Karabakh. -

The-Encyclopedia-Of-Cardplay-Techniques-Guy-Levé.Pdf

© 2007 Guy Levé. All rights reserved. It is illegal to reproduce any portion of this mate- rial, except by special arrangement with the publisher. Reproduction of this material without authorization, by any duplication process whatsoever, is a violation of copyright. Master Point Press 331 Douglas Ave. Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5M 1H2 (416) 781-0351 Website: http://www.masterpointpress.com http://www.masteringbridge.com http://www.ebooksbridge.com http://www.bridgeblogging.com Email: [email protected] Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Levé, Guy The encyclopedia of card play techniques at bridge / Guy Levé. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-55494-141-4 1. Contract bridge--Encyclopedias. I. Title. GV1282.22.L49 2007 795.41'5303 C2007-901628-6 Editor Ray Lee Interior format and copy editing Suzanne Hocking Cover and interior design Olena S. Sullivan/New Mediatrix Printed in Canada by Webcom Ltd. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11 10 09 08 07 Preface Guy Levé, an experienced player from Montpellier in southern France, has a passion for bridge, particularly for the play of the cards. For many years he has been planning to assemble an in-depth study of all known card play techniques and their classification. The only thing he lacked was time for the project; now, having recently retired, he has accom- plished his ambitious task. It has been my privilege to follow its progress and watch the book take shape. A book such as this should not to be put into a beginner’s hands, but it should become a well-thumbed reference source for all players who want to improve their game. -

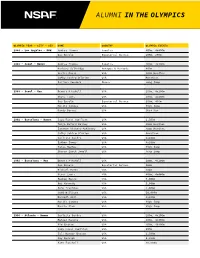

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

Lexical Patterns As Lie Detectors in Donald Trump's Tweets

International Journal of Communication 14(2020), 5237–5260 1932–8036/20200005 Beyond Fact-Checking: Lexical Patterns as Lie Detectors in Donald Trump’s Tweets DORIAN HUNTER DAVIS Webster University, USA ARAM SINNREICH American University, USA Journalists often debate whether to call Donald Trump’s falsehoods “lies” or stop short of implying intent. This article proposes an empirical tool to supplement traditional fact- checking methods and address the practical challenge of identifying lies. Analyzing Trump’s tweets with a regression function designed to predict true and false claims based on their language and composition, it finds significant evidence of intent underlying most of Trump’s false claims, and makes the case for calling them lies when that outcome agrees with the results of traditional fact-checking procedures. Keywords: Donald Trump, fact-checking, journalism, lying, Twitter, truth-default theory According to The Washington Post’s Fact Checker, Donald Trump has uttered more than 20,000 false or misleading statements since taking office (Kessler, Rizzo, & Kelly, 2020b). Several fact-checks of his political rallies have found that between two thirds and three quarters of his claims are false or baseless (Rizzo, 2020). Because false claims are a hallmark of the Trump presidency (Kessler, Rizzo, & Kelly, 2020a), there has been no shortage of news organizations willing to call at least one of Trump’s false statements a “lie,” and some publications have made liberal use of that term. But discerning honest mistakes from “willful, deliberate attempt[s] to deceive” (Baker, 2017, para. 12) requires a degree of judgment, and some newsrooms have been reluctant to infer intent. -

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number: 165 UK £3.95 Europe €5.00 September 2016 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz This month we are dealing with all sorts of conventions. You are West in the auctions below, BRIDGEplaying ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and four-card majors. 1. Dealer South. Love All. 4. Dealer East. N/S Game. 7. Dealer East. Love All. 10. Dealer North. Love All. ♠ K Q 3 ♠ A 6 ♠ A Q 4 3 ♠ 6 2 ♥ K 4 3 2 N ♥ J 9 7 6 N ♥ 7 6 ♥ Q 2 N W E W E N W E ♦ K 7 6 ♦ A 9 8 3 2 ♦ Q J 10 8 ♦ A 8 7 3 S S W E S ♣ Q J 2 ♣ 6 5 ♣ J 8 2 ♣ A 9 8 5 4 S West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 2♠1 1NT 2♣1 1♥ 2♥1 1♣1 Dbl 1♠ ? 1Weak two ? ? ? 1May have just one club 1Hearts and another suit (5-4+) 1Michaels cue bid: 5-5 in ♠ & ♣ or ♦ (five-card majors and a strong 1NT) 2. Dealer North. E/W Game. 5. Dealer West. Love All. 8. Dealer West. Love All. 11. Dealer North. Love All. ♠ 7 ♠ A Q 7 6 ♠ A K 7 5 ♠ A 7 6 3 N ♥ Q 8 7 6 N ♥ 3 2 N ♥ K Q 7 6 5 ♥ 6 5 4 N W E ♦ W E ♦ W E ♦ ♦ W E A 9 8 5 3 J 4 3 J 8 7 S 9 8 S S S ♣ K 9 6 ♣ A Q 10 3 ♣ 2 ♣ K Q J 10 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 2♠1 Pass Pass 1NT Pass Pass 2♣1 1♥ 2NT1 Dbl Pass 1♣1 Dbl 1♠ ? 1Weak two ? ? Pass 1NT Pass Pass 1Hearts and another suit (5-4+) 1Unusual no-trump: 5-5 in ♣ & ♦ ? 1May have just one club (five-card majors and a strong 1NT) 3.