APA Format 6Th Edition Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uhm Phd 9519439 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106·1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Order Number 9519439 Discourses ofcultural identity in divided Bengal Dhar, Subrata Shankar, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 U·M·I 300N. ZeebRd. AnnArbor,MI48106 DISCOURSES OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DIVIDED BENGAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 1994 By Subrata S. -

Pratham Pratisruti, Subarnalata and Bakulkatha

A Tri-Generational Odyssey: Ashapurna Deviís Trilogy: Reading Pratham Pratisruti, Subarnalata and Bakulkatha SANJUKTA DASGUPTA Ashapurna Devi (1909-1995) an extraordinarily prolific Ashapurnaís fictional representations is beyond question Bengali woman writer and interestingly a close for she is one woman writer of twentieth century Bengal contemporary of French feminist philosopher and writer who was not readily contaminated by English language Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) however needs an and literature. As she never went to school and was introduction outside India. therefore unacquainted with formal English education, Born in colonial India in 1909, self-taught Ashapurna looked upon by the Bengali as initiation into the charmed Devi went on to write one hundred and eighty nine novels precincts of power and prestige, Ashapurnaís Bengali is and around a thousand short stories and also four not interspersed with English loan words, a common hundred stories for children. Ashapurna never went to weakness in many Bengali writers. The Bengali idiom that school but became literate by merely watching and Ashapurna chose to express herself in was derived from imitating her elder brother practice reading and writing the well-known and well-worn contours of the domestic as his school exercises. But unlike many Bengali girls in space of the indigenous Bengali milieu. Dialogues of her those days Ashapurna had the privilege of having for characters belonging to various age groups incorporated her mother a literate middle class woman whose pastime the resonance of the region specific spoken rhythm was reading. Ashapurna too became a compulsive reader redolent of a home spun idiom, a remarkable peculiarity but mere reading did not satisfy her. -

MA BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department Of

M.A. BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department of Bengali, Bhasa Bhavana Visva Bharati, Santiniketan Total No- 800 Total Course No- 16 Marks of Per Course- 50 SEMESTER- 1 Objective : To impart knowledge and to enable the understanding of the nuances of the Bengali literature in the social, cultural and political context Outcome: i) Mastery over Bengali Literature in the social, cultural and political context ii) Generate employability Course- I History of Bengali Literature (‘Charyapad’ to Pre-Fort William period) An analysis of the literature in the social, cultural and political context The Background of Bengali Literature: Unit-1 Anthologies of 10-12th century poetry and Joydev: Gathasaptashati, Prakitpoingal, Suvasito Ratnakosh Bengali Literature of 10-15thcentury: Charyapad, Shrikrishnakirtan Literature by Translation: Krittibas, Maladhar Basu Mangalkavya: Biprodas Pipilai Baishnava Literature: Bidyapati, Chandidas Unit-2 Bengali Literature of 16-17th century Literature on Biography: Brindabandas, Lochandas, Jayananda, Krishnadas Kabiraj Baishnava Literature: Gayanadas, Balaramdas, Gobindadas Mangalkabya: Ketakadas, Mukunda Chakraborty, Rupram Chakraborty Ballad: Maymansinghagitika Literature by Translation: Literature of Arakan Court, Kashiram Das [This Unit corresponds with the Syllabus of WBCS Paper I Section B a)b)c) ] Unit-3 Bengali Literature of 18th century Mangalkavya: Ghanaram Chakraborty, Bharatchandra Nath Literature Shakta Poetry: Ramprasad, Kamalakanta Collection of Poetry: Khanadagitchintamani, Padakalpataru, Padamritasamudra -

The Era of Science Enthusiasts in Bengal (1841-1891): Akshayakumar, Vidyasagar and Rajendralala

Indian Journal of History of Science, 47.3 (2012) 375-425 THE ERA OF SCIENCE ENTHUSIASTS IN BENGAL (1841-1891): AKSHAYAKUMAR, VIDYASAGAR AND RAJENDRALALA ARUN KUMAR BISWAS* (Received 14 March 2012) During the nineteenth century, the Indian sub-continent witnessed two distinct outbursts of scientific enthusiasm in Bengal: one led by Rammohun Roy and his compatriots (1820-1840) and the other piloted by Mahendralal Sircar and Eugene Lafont (1860-1910). The intermediate decades were pioneered by the triumvirate: Akshayakumar, Vidyasagar, Rajendralala and a few others. Several scientific journals such as Tattvabodhinī Patrika–, Vivida–rtha Samgraha, Rahasya Sandarbha etc dominated the intellectual environment in the country. Some outstanding scientific books were written in Bengali by the triumvirate.Vidyasagar reformed the science content in the educational curricula. Akshayakumar was a champion in the newly emerging philosophy of science in India. Rajendralala was a colossus in the Asiatic Society, master in geography, archaeology, antiquity studies, various technical sciences, and proposed a scheme for rendering European scientific terms into vernaculars of India. There was a separate Muslim community’s approach to science in the 19th Century India. Key words: Akshayakumar, Botanical Collection, Geography, Muslim Community approach to Science, Phrenology, Rajendralala, Science enthusiasts (1841-1891), Technical Sciences, Triumvirate, Positivism, Vidyasagar INTRODUCTION It can be proposed that the first science movement in India was chiefly concentrated in the city of Calcutta and spanned the period of approximately quarter of a century (1814-39) coinciding with the entry of *Flat 2A, ‘Kamalini’ 69A, Townshend Road, Kolkata-700026 376 INDIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY OF SCIENCE Rammohun in the city and James Prinsep’s departure from it. -

Sita Devi-Shanta Devi and Women's Educational Development in 20 Century Bengal

Volume : 1 | Issue : 1 | January 2012 ISSN : 2250 - 1991 Research Paper Education Sita Devi-Shanta Devi and Women's Educational Development in 20th Century Bengal * Prarthita Biswas * Asst. Prof., Pailan College of Education, Joka, Kolkata ABSTRACT This synopsis tries to investigate the cultural as well as educational development of women of the 20th Century Bengali society which has been observed in the writing writings of Shanta Devi and Sita Devi concerning women and to examine in details about the women's literary works during that time. It would be fruitful to historically review the short stories as well as the novels of both Shanta Devi and Sita Devi to get a critical understanding about the various spheres they touched many of which are still being debated till date. The study may not be able to settle the debates going on for centuries about women emancipation and specially about women's educational development in 20th Century Bengal but will sincerely attempt to help scholars think in a more practical and objective manner . Keywords : Women's Education, Emancipation, Literary Works, Women's Enlightenment Introduction 1917, Sita Devi's first original short story Light of the Eyes appeared in Prabasi, her sister's first one Sunanda appearing he two sisters, Sita Devi and Shanta Devi from whose in the same magazine a month later. work a selection is translated and offered to the In 1918, they wrote in collaboration a novel, “Udyanlata” (The TEnglish-reading public are daughters of Sri Garden Creeper in English) , a serial for Prabasi. This was Ramananda Chatterjee, a well-known personality and who given over a column in the Times Literary Supplement, from the launched “Prabasi Patrika” in the year 1901. -

19Th Century Women Emancipation Movement and Bengali Theatre

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD ISSN: 2455-0620 Volume - 5, Issue - 6, June – 2019 Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal with IC Value: 86.87 Scientific Journal Impact Factor: 6.497 Received on : 13/06/2019 Accepted on : 22/06/2019 Publication Date: 30/06/2019 19th Century Women Emancipation Movement and Bengali Theatre Dr. Dani Karmakar Guest Teacher, Department of Drama, Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Email - [email protected] Abstract: In the nineteenth century, the expansion of Western education and Culture led to the emergence of rational progressive ideas in the minds of Bengali youth. The society started roaring against Hindu inhuman customs as sati, polygamy, child marriage and the caste system. As a result, the brutal Sati was abolished. 'Widow Remarriage Act' was formulated. In the second half of the nineteenth century, due to the spread of institutional education for women, progressive thinking spread among women. Women's position in society and women's rights highlighted through stories, novels, plays, essays and autobiographies. After taking higher education, someone went to study medicine in Europe, someone became the Principal of the college, and someone joined other jobs. Bengali Theatre was influenced by these social movements of women. In Bengali theater, situation of women's misery were also presented. Some playwright quizzed against women emancipation movement. Actresses started perform in Bengali Theatre. The women wrote many plays. So nineteenth century was the century of emancipation movement. In this century women became aware their own individuality. The women awakening in this nineteenth century shows an example of revolutionary feminism. -

A Nineteenth-Century Bengali Housewife and Her Robinson Crusoe Days: Travel and Intimacy in Kailashbashini Debi’S the Diary of a Certain Housewife

Feminismo/s 36, December 2020, 49-76 ISSN: 1989-9998 A NINETEENTH-CENTURY BENGALI HOUSEWIFE AND HER ROBINSON CRUSOE DAYS: TRAVEL AND INTIMACY IN KAILASHBASHINI DEBI’S THE DIARY OF A CERTAIN HOUSEWIFE UN AMA DE CASA BENGALÍ DEL SIGLO DIECINUEVE Y SUS DÍAS COMO ROBINSON CRUSOE: VIAJES E INTIMIDAD EN THE DIARY OF A CERTAIN HOUSEWIFE DE KAILASHBASHINI DEBI Swati MOITRA Author / Autora: Abstract primera Swati Moitra Gurudas College, University of Calcutta Kailashbashini Debi’s Janaika Grihabadhu’r Calcutta, India [email protected] Diary (The Diary of a Certain Housewife; writ- https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3448-4915 ten between 1847 and 1873, serialised almost a century later in the monthly Basumati in Submitted / Recibido: 02/03/2020 Accepted / Aceptado: 02/05/2020 1952) chronicles her travels along the water- ways of eastern Bengal. Her travels are firmly To cite this article / Para citar este artículo: Moitra, Swati. «A nineteenth-century bengali centred around her husband’s work; in his housewife and her Robinson Crusoe days: absence, she is Robinson Crusoe, marooned Travel and intimacy in Kailashbashini in the hinterlands of Bengal with only her Debi’s The diary of a certain housewife». In Feminismo/s, 36 (December 2020): daughter. 49-76. Monographic dossier / Dosier Bearing in mind the gendered limitations monográfico: Departures and Arrivals: Women, on travel in the nineteenth century for upper- Mobility and Travel Writing / Salidas y llegadas: mujeres, movilidad y escritura de viajes, Raquel caste Bengali women, this essay investigates García-Cuevas García y Sara Prieto García- Kailashbashini Debi’s narration of her travels Cañedo (coords.), https://doi.org/10.14198/ fem.2020.36.03 and the utopic vision of the modern housewife that Kailashbashini constructs for herself. -

Analysis of Reflection of the Swadeshi Movement (1905) in Contemporary Periodicals

International Journal of Innovative Research and Advanced Studies (IJIRAS) ISSN: 2394-4404 Volume 7 Issue 4, April 2020 Analysis Of Reflection Of The Swadeshi Movement (1905) In Contemporary Periodicals Dr. Sreyasi Ghosh Assistant Professor and HOD of History Dept., Hiralal Mazumdar Memorial College for Women, Dakshineshwar, Kolkata, India Abstract: In this study related to the Anti- Partition Movement (1905- 1911) of Bengal/ India I have tried my level best to show how prominence and impact of the Swadeshi phase had been reflected in contemporary newspapers and periodicals quite skilfully. The movement which had its so cio- cultural roots in the decade of 1870s was undoubtedly one of the most creative phases of modern India. Binay Sarkar had rightly opined that the movement mentioned above should be termed as Bangabiplab. Secret pamphlets, police records, personal papers/ diary of contemporary leaders , memoirs/ reminiscences, autobiographies etc. were very important while writing History of the Anti- Partition Movement but according to my view based on research on this period reflection of the period was utmost skilful in pages of contemporary newspapers and periodicals. Ideology of unity of Bengal, boycott, swadeshi, national education and theory of Swaraj were most important pillars on which the movement discussed here was established and all these themes with impact of it on literature, music, painting, nationalist science etc. could be found through contemporary daily, weekly and monthly English/Bengali periodicals. Dawn, New India, Modern Review, Bharati, Prabasi, Bangadarshan (Nabaparyyay), Bengalee, Bande Mataram, Sanjivani, Sandhya, Yugantar, Swaraj were prominent mouthpieces through which History of this epoch- making and illustrious movement could be written with a lot of ease. -

Vaishnava Ideology in Rabindranath Tagore's Eco-Poetry and Its

International Seminar on “Vaishnava Philosophy and Ecology” jointly organised by Dept. of Philosophy, Ruia Autonomous College and Bhakti Vedanta Vidyapith Research Centre, 15th December 2017 Vaishnava Ideology in Rabindranath Tagore’s Eco-poetry and its philosophical significance in human-nature relationship Kamala Srinivas Assistant Professor Department of Philosophy SIES College of Arts, Science & Commerce, Sion (West), Mumbai Email i.d.: [email protected] Contact No.: +91 9820620224 Abstract “In the infinite dualism of death and life there is a harmony. We know that the life of a soul which is finite in its expression and infinite in its principle, must go through the portals of death in its journey to realise the infinite.” - Rabindranath Tagore Rabindranath Tagore, India’s renaissance man in whom tradition and culture blended and evolved in the course of his long life due to the exposure to a wide range of ideas and lifestyles both from east and west. We get to appraise the fact these ideas absorbed, modified, supplemented and shaped in his poetic consciousness. Many of his later writings had an influence of Vaishnava Philosophy and Literature. In Bhanusimher Padaboli, one can trace his literary concepts having an influence of Vaishnava lyrics. It is the explicit compilation that showcase Tagore in relation to the Krishna-Chaitanya religio-literary tradition of Bengal. He creatively synthesized central themes of Vaishnava poetic words such as madhurya, viraha, abhisara, bhakti, lila, sadhana and shakti in his masterpiece plays, poems, paintings and musical compositions giving all of them a mystical human garb. The paper initially engages with his family’s Vaishnava affinities. -

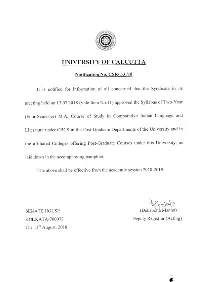

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR 1. Title and Commencement: 1.1 These Regulations shall be called THE REGULATIONS FOR SEMESTERISED M.A. in Comparative Indian Language and Literature Post- Graduate Programme (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) 2018, UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA. 1.2 These Regulations shall come into force with effect from the academic session 2018-2019. 2. Duration of the Programme: The 2-year M.A. programme shall be for a minimum duration of Four (04) consecutive semesters of six months each/ i.e., two (2) years and will start ordinarily in the month of July of each year. 3. Applicability of the New Regulations: These new regulations shall be applicable to: a) The students taking admission to the M.A. Course in the academic session 2018-19 b) The students admitted in earlier sessions but did not enrol for M.A. Part I Examinations up to 2018 c) The students admitted in earlier sessions and enrolled for Part I Examinations but did not appear in Part I Examinations up to 2018. d) The students admitted in earlier sessions and appeared in M.A. Part I Examinations in 2018 or earlier shall continue to be guided by the existing Regulations of Annual System. 4. Attendance 4.1 A student attending at least 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. 4.2 A student attending at least 60% but less than 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to the payment of prescribed condonation fees and fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. -

Fiction As Resistance: Perspectives from Colonial and Contemporary Bengal Aparna Bandyopadhyay

Vidyasagar University Journal of History, Volume V, 2016-2017, Pages: 94-106 ISSN 2321-0834 Fiction as Resistance: Perspectives from Colonial and Contemporary Bengal Aparna Bandyopadhyay The proposed paper will focus on fictional literaturepenned by women incolonial and contemporary Bengal and see such fiction as resistance to patriarchy. It will examine the practice and practicalities of writing in a milieu that was and to a great extent still is inhospitable to women’s intellectual development and creativity, and also reveal the diverse strategies adopted by women to subvert patriarchal attempts to constrict their creativity and control their lives and leisure.Writing fiction moreover, appears to serve for womenthe purpose of a safety valve for the release of the pent-up frustrations, agonies and unfulfilled cravings. Though their fiction they have soughtto resolve their inner dilemmas and the questions that plague them. Finally,women novelists often tend to write their own lives into their fiction, merging their own selves with those of their women protagonists, their protagonists becoming their alter ego. Their fiction then becomes the vehicle through which they protest the oppression that they had been subjected to in their personal lives and also tell the world how they either chose the path of compromise and subservience or overcame odds, broke shackles, and eventually assumed control of their own lives.The paper will especially focus on Ashalata Singha’s JeevanDhara, Maitreyee Devi’s Na Hanyate, Mandakranta Sen’s Jhanptaal, Tilottoma Majumdar’s Ektara, and Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay’s Sankhini and will see howthese novelists sought to pen a bildungsroman of the woman writer whose creativity was dialectically linked to a turbulent and oppressive marital life, recording the eventual surrender to or triumph over patriarchal mores. -

Role of Women and Women's Organisation

International Journal of Advanced Research and Development International Journal of Advanced Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4030 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.advancedjournal.com Volume 3; Issue 3; May 2018; Page No. 1304-1307 Role of women and women's organisation Nidhi Sonkar Department of Political Science, University of Allahabad, Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, India Abstract The course of the Indian national Movement is marked by multi faceted and complex stages. The question of social reform remained alive in the nationalist debates in the public sphere from late 19th century till 1947. Women's consciousness around social and the national questions grew simultaneously. Both Indian men and women were leading the social reform movements from the 1880's. In various women autobiographies and writings from all over India, particularly Maharashtra and Bengal, the slogan that 'Personal is Political' was being raised. The paper is based on secondary data. The data has been taken from status of women is India. The paper will attempt to analyze Demographic profile of women in India, women's movement and organizations. The paper will also discuss the role and achievements of women's organization, women is the nationalist movement and so on. Keywords: national women, personal is political, demographic, organizations Introduction Committee on the Status of Women in India. This Committee, Status of Women in India which was set up by the Government of India at the request of Ironically, in the Indian situation where women goddesses are the United Nations, looked into various indicators to evaluate worshipped, women are denied an independent identity and the status of women in India.