The Ties That Bind in Numbers 26–36

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Significance of "Knees"

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF "KNEES" We are told in the scriptures that Rachael was jealous of her sister Leah because Rachael was barren and Leah was able to bear children. Rachael went to Jacob and said: "Behold my maid Bilhah, go in and lie with her; and she shall bear upon my knees that I may also have children by her." Gen. 30:3 Jacob did have a child with Bilhah, and Rachael adopted Dan as soon as he was born, and he became her son. This act by Rachael concerning her knees was an act of adoption. The ages of Manasseh and Ephraim cannot be exactly determined, but we know that they were born when Joseph was between the age of 30 and 37 (Gen. 41:46-52). We are not told whether they are twins, or, if they are not twins, how many years are between their births. To find out how old they were when Jacob came into Egypt we must take Joseph's age when Jacob arrived, which is 39 and subtract the age of Joseph when they were born (30-37). For our purposes we will take the greater age to make his sons as young as they might have been (39-37=2). Therefore, the youngest that Joseph's sons could have been was 2 years of age when Jacob arrived in Egypt. The oldest possibility would have been 9 years of age. Joseph's two sons were blessed by their grandfather, Jacob (Israel), but it appears that Jacob did not bless Manasseh and Ephraim until he was near death. -

Immorality on the Border Lesson #11 for December 12, 2009 Scriptures: Numbers 25; 31; Deuteronomy 21:10-14; 1 Corinthians 10:1-14; Revelation 2:14

People on the Move: The Book of Numbers Immorality on the Border Lesson #11 for December 12, 2009 Scriptures: Numbers 25; 31; Deuteronomy 21:10-14; 1 Corinthians 10:1-14; Revelation 2:14. 1. This lesson is a discussion about the disastrous results of Balaam’s work with the people of Midian and Moab and the seduction of the children of Israel leading to the death of 24,000 Israelites. It is a lesson about things that “nice people” do not talk about. 2. By the time of the “encounter” with Balaam, the children of Israel–who forty years earlier had been frightened terribly by the report of the ten spies–had seen God work with their soldiers in conquering three nations and were resting at ease in the small plain east of the Jordan River where they could look across the river and see Jericho a few miles away. 3. What were they waiting for? Was Moses busy writing the book of Deuteronomy–a summary of three sermons that Moses was asked to give to the children of Israel? Were they working out the details of the division of the land of Canaan? How did they divide up a land that none of them–except for the parts that Caleb and Joshua had “spied out”–had ever seen? They had no pictures and no maps. They had only what God may have shown Moses. Surely, God understood the hazard that was present in that setting of idleness. Why do you think He allowed them to camp there for some time? They were camped in a small flat area below the hills of Moab. -

Hebrew 7602 AU17.Pdf

Attention! This is a representative syllabus. The syllabus for the course you are enrolled in will likely be different. Please refer to your instructor’s syllabus for more information on specific requirements for a given semester. HEBREW 7602 STUDIES IN HEBREW PROSE: THE PROBLEM OF EVIL IN BIBLICAL & POST-BIBLICAL HEBREW LITERATURE Autumn 2017 Meeting Time/Location Instructor: Office Hours: Phone: Email: Class will not meet on September 21 and October 5 DESCRIPTION: If there is a God, and He is all-powerful, all-knowing, and wholly benevolent, how can evil exist? The BibLe raises this question — the problem of evil — many times in different contexts and ways. Through extensive reading in primary and secondary sources relating to theodicies, students wilL gain an appreciation of religious thought among the ancient Israelites and their Near Eastern neighbors as well as later Jewish approaches to theodicy. All readings will be done in Hebrew, but use of English Bibles outside of class is permitted. OBJECTIVES: 1. to introduce students to the problem of evil in the Hebrew BibLe and certain postbiblical texts. 2. to acquaint students with the ancient contexts in which Jewish theodicies developed. 3. to familiarize students with key scholarly discussions of the subject. 4. to develop students’ facility with reading and analyzing biblical Hebrew prose. CLASSWORK: 1. Students are expected to attend aLL classes. In the event of absence, pLease contact other students for material covered in class. Please notify the instructor in advance of any unavoidable absences. 2. Students are expected to participate in class. 3. Students are expected to arrive punctuaLLy for class. -

Parshat Matot/Masei

Parshat Matot/Masei A free excerpt from the Kehot Publication Society's Chumash Bemidbar/Book of Numbers with commentary based on the works of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, produced by Chabad of California. The full volume is available for purchase at www.kehot.com. For personal use only. All rights reserved. The right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, in any form, requires permission in writing from Chabad of California, Inc. THE TORAH - CHUMASH BEMIDBAR WITH AN INTERPOLATED ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY BASED ON THE WORKS OF THE LUBAVITCHER REBBE Copyright © 2006-2009 by Chabad of California THE TORAHSecond,- revisedCHUMASH printingB 2009EMIDBAR WITH AN INTERPOLATED ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARYA BprojectASED ON of THE WORKS OF ChabadTHE LUBAVITCH of CaliforniaREBBE 741 Gayley Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024 310-208-7511Copyright / Fax © 310-208-58112004 by ChabadPublished of California, by Inc. Kehot Publication Society 770 Eastern Parkway,Published Brooklyn, by New York 11213 Kehot718-774-4000 Publication / Fax 718-774-2718 Society 770 Eastern Parkway,[email protected] Brooklyn, New York 11213 718-774-4000 / Fax 718-774-2718 Order Department: 291 KingstonOrder Avenue, Department: Brooklyn, New York 11213 291 Kingston718-778-0226 Avenue / /Brooklyn, Fax 718-778-4148 New York 11213 718-778-0226www.kehot.com / Fax 718-778-4148 www.kehotonline.com All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book All rightsor portions reserved, thereof, including in any the form, right without to reproduce permission, this book or portionsin writing, thereof, from in anyChabad form, of without California, permission, Inc. in writing, from Chabad of California, Inc. The Kehot logo is a trademark ofThe Merkos Kehot L’Inyonei logo is a Chinuch,trademark Inc. -

Lesson 5: the Book of Numbers

UCF Tuesday Night Bible Study UCF - Tuesday Night Bible St... Page 1 of 6 Lesson 5: The Book of Numbers Numbers covers about 38 years of desert wandering by the Israelites. It is called Numbers because it includes two numberings of the men of war, in chapters 1-4 and 26-27. The first numbering was made the second year after the Israelites left Egypt. Then, with Judah leading the way, each tribe was given a position in the march to Canaan. From this point on, Numbers is a wilderness book. It describes the failure of Israel at Kadesh-Barnea and their wilderness wanderings until the unbelieving generation died, after which the second numbering took place. This book has been described as the "longest funeral march in history." An interesting fact to note is the nation of Israel did not grow during its wilderness wanderings. In fact, they declined in number by almost 2,000 men of war. Thus, they wasted 38 years, suffered unnecessary afflictions, and did not grow numerically. This is what unbelief does to the Christian; it produces wasted time, wasted effort, and spiritual stalemate. Numbers has many spiritual lessons for us today, as explained in Hebrews 3-4 and 1 Corinthians 10:6-10. Read the passage in 1 Corinthians, and explain what it says the book of Numbers should teach us today: Brief Outline of the Book: I. Preparations for the Wilderness (1:1-10:10) II. Wanderings (10:11-21:35) III. The Balaam Incident (chps. 22-25) IV. Preparations To Enter Canaan (chps. -

Manasseh: Reflections on Tribe, Territory and Text

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Vanderbilt Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive MANASSEH: REFLECTIONS ON TRIBE, TERRITORY AND TEXT By Ellen Renee Lerner Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion August, 2014 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Douglas A. Knight Professor Jack M. Sasson Professor Annalisa Azzoni Professor Herbert Marbury Professor Tom D. Dillehay Copyright © 2014 by Ellen Renee Lerner All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people I would like to thank for their role in helping me complete this project. First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee: Professor Douglas A. Knight, Professor Jack M. Sasson, Professor Annalisa Azzoni, Professor Herbert Marbury, and Professor Tom Dillehay. It has been a true privilege to work with them and I hope to one day emulate their erudition and the kind, generous manner in which they support their students. I would especially like to thank Douglas Knight for his mentorship, encouragement and humor throughout this dissertation and my time at Vanderbilt, and Annalisa Azzoni for her incredible, fabulous kindness and for being a sounding board for so many things. I have been lucky to have had a number of smart, thoughtful colleagues in Vanderbilt’s greater Graduate Dept. of Religion but I must give an extra special thanks to Linzie Treadway and Daniel Fisher -- two people whose friendship and wit means more to me than they know. -

Numbers 36 Commentary

Numbers 36 Commentary PREVIOUSNumbers: Journey to God's Rest-Land by Irving Jensen- used by permission NEXT Source: Ryrie Study Bible THE BOOK OF NUMBERS "Wilderness Wandering" WALKING WANDERING WAITING Numbers 1-12 Numbers 13-25 Numbers 26-36 Counting & Cleansing & Carping & 12 Spies & Aaron & Serpent of Second Last Days of Sections, Camping Congregation Complaining Death in Levites in Brass & Census 7 Moses as Sanctuaries & Nu 1-4 Nu 5-8 Nu 9-12 Desert Wilderness Story of Laws of Leader Settlements Nu 13-16 Nu 17-18 Balaam Israel Nu 31-33 Nu 34-36 Nu 21-25 Nu 26-30 Law Rebellion New Laws & Order & Disorder for the New Order Old Tragic New Generation Transition Generation Preparation for the Journey: Participation in the Journey: Prize at end of the Journey: Moving Out Moving On Moving In At Sinai To Moab At Moab Mt Sinai Mt Hor Mt Nebo En Route to Kadesh En Route to Nowhere En Route to Canaan (Mt Sinai) (Wilderness) (Plains of Moab) A Few Weeks to 38 years, A Few 2 Months 3 months, 10 days Months Christ in Numbers = Our "Lifted-up One" (Nu 21:9, cp Jn 3:14-15) Author: Moses Numbers 36:1 And the heads of the fathers' households of the family of the sons of Gilead, the son of Machir, the son of Manasseh, of the families of the sons of Joseph, came near and spoke before Moses and before the leaders, the heads of the fathers' households of the sons of Israel, BGT Numbers 36:1 κα προσλθον ο ρχοντες φυλς υν Γαλααδ υο Μαχιρ υο Μανασση κ τς φυλς υν Ιωσηφ κα λλησαν ναντι Μωυσ κα ναντι Ελεαζαρ το ερως κα ναντι τν ρχντων οκων πατριν υν Ισραηλ NET Numbers 36:1 Then the heads of the family groups of the Gileadites, the descendant of Machir, the descendant of Manasseh, who were from the Josephite families, approached and spoke before Moses and the leaders who were the heads of the Israelite families. -

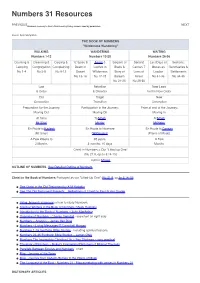

Numbers 31 Resources

Numbers 31 Resources PREVIOUSNumbers: Journey to God's Rest-Land by Irving Jensen- used by permission NEXT Source: Ryrie Study Bible THE BOOK OF NUMBERS "Wilderness Wandering" WALKING WANDERING WAITING Numbers 1-12 Numbers 13-25 Numbers 26-36 Counting & Cleansing & Carping & 12 Spies & Aaron & Serpent of Second Last Days of Sections, Camping Congregation Complaining Death in Levites in Brass & Census 7 Moses as Sanctuaries & Nu 1-4 Nu 5-8 Nu 9-12 Desert Wilderness Story of Laws of Leader Settlements Nu 13-16 Nu 17-18 Balaam Israel Nu 31-33 Nu 34-36 Nu 21-25 Nu 26-30 Law Rebellion New Laws & Order & Disorder for the New Order Old Tragic New Generation Transition Generation Preparation for the Journey: Participation in the Journey: Prize at end of the Journey: Moving Out Moving On Moving In At Sinai To Moab At Moab Mt Sinai Mt Hor Mt Nebo En Route to Kadesh En Route to Nowhere En Route to Canaan (Mt Sinai) (Wilderness) (Plains of Moab) A Few Weeks to 38 years, A Few 2 Months 3 months, 10 days Months Christ in Numbers = Our "Lifted-up One" (Nu 21:9, cp Jn 3:14-15) Author: Moses OUTLINE OF NUMBERS- See Detailed Outline of Numbers Christ in the Book of Numbers: Portrayed as our "Lifted-Up One" (Nu 21:9, cp Jn 3:14-15) See Christ in the Old Testament by A M Hodgkin See The Old Testament Presents... Reflections of Christ by Paul R Van Gorder Irving Jensen's summaryon how to study Numbers Spiritual Warfare in the Book of Numbers-Chuck Huckaby Introduction to the Book of Numbers – John MacArthur Overview of Numbers - Charles Swindoll - see chart -

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 Author(s): Lewis Bayles Paton Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259319 . Accessed: 09/04/2012 16:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXXII Part I 1913 Israel's Conquest of Canaan Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 LEWIS BAYLES PATON HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY problem of Old Testament history is more fundamental NO than that of the manner in which the conquest of Canaan was effected by the Hebrew tribes. If they came unitedly, there is a possibility that they were united in the desert and in Egypt. If their invasions were separated by wide intervals of time, there is no probability that they were united in their earlier history. Our estimate of the Patriarchal and the Mosaic traditions is thus conditioned upon the answer that we give to this question. -

Book Study – the Torah

Book Study – The Torah A tool to help with reading the Bible. Produced by XA Denton Chi Alpha | UNT & TWU Introduction: In the first book of the Torah, Genesis, we see God create a good and perfect world. Included in His creation was mankind, which was to act as God's representatives on earth. Mankind, however, had other ideas and chose to define what was good and evil for themselves. After this decision, things get bad for mankind – so bad that God has to eventually destroy them all with the flood and start over. This represents the beginning of God's mission to rescue and restore His world. To begin this mission, God raises up Abraham and promises him that through his descendants all of the nations of the world would come to know God's blessing. It turns out, though, that Abraham and his descendants were a pretty dysfunctional family. However, in spite of their mishaps, God still continues to use them for His plan. This brings us to the second book of the Torah, Exodus. Here, the Israelites are enslaved to the Egyptians, and the first half of the book focuses on how God raises up Moses to deliver His people from the Egyptians. God saves His people from the Egyptians, but now they are a nation without a home, wandering in the desert and unsure why God saved them in the first place. From this point forward, we see God begin to try and restore His presence among His People. He comes down on Mount Sinai, gives Moses the Ten Commandments, and gives instructions on how the Israelites should build a temple – a place where God will be able to live among them. -

Numbers 25 Commentary

Numbers 25 Commentary PREVIOUSNumbers: Journey to God's Rest-Land by Irving Jensen- used by permission NEXT Source: Ryrie Study Bible THE BOOK OF NUMBERS "Wilderness Wandering" WALKING WANDERING WAITING Numbers 1-12 Numbers 13-25 Numbers 26-36 Counting & Cleansing & Carping & 12 Spies & Aaron & Serpent of Second Last Days of Sections, Camping Congregation Complaining Death in Levites in Brass & Census 7 Moses as Sanctuaries & Nu 1-4 Nu 5-8 Nu 9-12 Desert Wilderness Story of Laws of Leader Settlements Nu 13-16 Nu 17-18 Balaam Israel Nu 31-33 Nu 34-36 Nu 21-25 Nu 26-30 Law Rebellion New Laws & Order & Disorder for the New Order Old Tragic New Generation Transition Generation Preparation for the Journey: Participation in the Journey: Prize at end of the Journey: Moving Out Moving On Moving In At Sinai To Moab At Moab Mt Sinai Mt Hor Mt Nebo En Route to Kadesh En Route to Nowhere En Route to Canaan (Mt Sinai) (Wilderness) (Plains of Moab) A Few Weeks to 38 years, A Few 2 Months 3 months, 10 days Months Christ in Numbers = Our "Lifted-up One" (Nu 21:9, cp Jn 3:14-15) Author: Moses Numbers 25:1 While Israel remained at Shittim, the people began to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab. Greek (Septuagint) kai katelusen (3SAAI: refresh oneself, lodge Lu 9:12;Ge 24:23 travelers loosening their own burdens when they stayed at a house on a journey) Israel en Sattin kai ebebelothe (3SAPI: bebeloo: cause to become unclean, profane, or ritually unacceptable - defile, profane.’disregarding what is to be kept sacred or holy: Mt12:5) ho laos ekporneusai (AAN: ekporneuo: indulged in flagrant immorality: see Jude 1:7) eis tas thugateras (daughters: Mt9:18) Moab Amplified ISRAEL SETTLED down and remained in Shittim, and the people began to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab, BGT Numbers 25:1 κα κατλυσεν Ισραηλ ν Σαττιν κα βεβηλθη λας κπορνεσαι ες τς θυγατρας Μωαβ NET Numbers 25:1 When Israel lived in Shittim, the people began to commit sexual immorality with the daughters of Moab. -

The Life and Psalms of David a Man After God’S Heart

These study lessons are for individual or group Bible study and may be freely copied or distributed for class purposes. Please do not modify the material or distribute partially. Under no circumstances are these lessons to be sold. Comments are welcomed and may be emailed to [email protected]. The Life and Psalms of David A Man After God’s Heart Curtis Byers 2015 The Life and Psalms of David Introduction The life of David is highly instructive to all who seek to be a servant of God. Although we cannot relate to the kingly rule of David, we can understand his struggle to live his life under the mighty hand of God. His success in that struggle earned him the honor as “a man after God’s own heart” (Acts 13:22). The intent of David’s heart is not always apparent by simply viewing his life as recorded in the books of Samuel. It is, however, abundantly clear by reading his Psalms. The purpose of this class will be to study the Psalms of David in the context of his life. David was a shepherd, musician, warrior, poet, friend, king, and servant. Although the events of David’s life are more dramatic than those in our lives, his battle with avoiding the wrong and seeking the right is the same as ours. Not only do his victories provide valuable lessons for us, we can also learn from his defeats. David had his flaws, but it would be a serious misunderstanding for us to justify our flaws because David had his.