Electronic Copy Available At: Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chancellor's Award

Chancellor’s Award 2013 The University of Reading is committed to rewarding and celebrating talent, hard work and achievement across its student community. We are therefore delighted to present our 2013 Chancellor’s Award winners. Those featured in this yearbook represent our brightest and best students from across the University’s broad range of academic disciplines. Award recipients are those students who achieved the highest results in their subject at the end of either their first or second year of study. We are extremely proud to be able to showcase such an inspiring group of individuals. 3 Chancellor’s Award | 2013 Student profiles List of all recipients of the Chancellor’s Award 2013 Below is a list of all those Part 1 and Part 2 students who have received the 2013 Chancellor’s Award for outstanding academic achievement. Only around 80 awards will be given each year, to those students who received the top marks in their subject area. Jennifer Agnew Ian Cho Kim Jackson Poppy Small Kate Alexander Kristina Chu Anup Kocheril Kurian Lucy Spencer Stefan Andreas Lucia Crowther Ryan L W Lee Laura Spencer Daniel Angelov Nicola D’Alessandro Ailsa Linnell Todd Spiers Louise Astill Georgia de Rohan Peter Loveland Stefanos Stefanov James Barnett Isobel Dench Robert Lowe Gemma Stobie Lucelia Barrand Albert Edwards Phil Marks Ravi Surendralal Simon Beck Tom Elliott Rachael McLaughlin Katie Swann Leanne Beveridge Paul Fairall Siobhan Monk Jonathan Tanner Tom Birdsell Anna Frey Laura Moody Minh Hieu Tran Chelsea Bond Daniel Gardner Annie Morton -

Download PDF (46.6

Contributors Edward I. Altman, Stern School of Business, New York University, New York, USA; [email protected]. Manuel Ammann, Swiss Institute of Banking and Finance, University of St Gallen, Switzerland; [email protected]. Keith Anderson, The York Management School, University of York, UK; keith. [email protected]. Adrian R. Bell, ICMA Centre, Henley Business School, University of Reading, UK; [email protected]. Chris Brooks, ICMA Centre, Henley Business School, University of Reading, UK; c.brooks@ icmacentre.ac.uk. David A. Carter, Department of Finance, College of Business Administration, Oklahoma State University, USA; [email protected]. Geraldo Cerqueiro, Universidade Católica Portuguesa Católica – Lisbon School of Business and Economics, Portugal; [email protected]. Ke Chen, Manchester Business School, University of Manchester, UK; kechen1998@ gmail.com. Hans Degryse, Department of Accountancy, Finance and Insurance, KU Leuven, Belgium, CentER – Tilburg University, The Netherlands, CEPR, and CESifo; hans. [email protected]. Deniz Erdemlioglu, University of Namur – FUNDP, Belgium; deniz.erdemlioglu@ fundp.ac.be. Andrey Golubov, Cass Business School, City University London, UK; andrey.golubov.1@ city.ac.uk. Massimo Guidolin, CAIR, Manchester Business School, University of Manchester, UK and IGIER, Bocconi University, Italy; [email protected]. Ólan T. Henry, University of Liverpool Management School, University of Liverpool, UK; [email protected]. Thomas Johann, University of Mannheim, -

Whiteknights-Campus-Map.Pdf

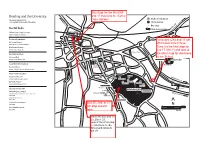

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Academic buildings Primary pedestrain and cycle routes Halls of residence A D A Secondary pedestrain RO S W Bus stop and cycle routes UPP ND H ER RED L A BROADOAK IT PLACE E K DUNSDEN N 1 Car parks Unsurfaced/unlit paths I CRESCENT G WANTAGE H CHILDS T S £ Pay & display Pedestrian ST R entrance GEORGES 84 OA D Car parks restricted to users of this building Pedestrian exit to STENTON Wokingham Road MACKINDER TOWNHOUSES D off-site housing A 202 TOWN CENTRE & O R WINDSOR, Accessible toilets LONDON ROAD T 295 PARK S EAT GREENOW & CAMPUS R U MCCOMBIE H STENTON Gender-neutral M TENNIS WESSEX B EL PARK toilets 2 253 3 34 39 71 16 1a £ 50 1 £ 30 BRIDGES 53 76 138 196 21 SHINFIELD ROAD 195 EARLEY GATE ENTRANCE SPORTS 26 ENTRANCE 9 135 4 GROUNDS 1 NORTHCOURT AVENUE S 5 H 29 54 I N 201 C F 27 I E L 55 D 37 8 R 259 7 20 O FRIENDS A 2 BRIDGE 56 BENYON D 6 33 15 9 21 7 70 40 ST PATRICKS 10 49 48 25 3 118 62 5 24 22 74 10 6 59 SHERFIELD 4 58 8 46 23 38 47 261 D 32 13 31 THE WILDERNESS 11 210 PEPPER LANE 186 ENTRANCE P E P D P A E O R R L HARRIS S A S N GARDEN E WHITEKNIGHTS CAMPUS E N R E SAT NAV RG6 6UR | RG6 7BE FOR EARLEY GATE D IL W E N 200M WHITEKNIGHTS MAP KEY (A–Z) Name and grid ref Building Name and grid ref Building Name and grid ref Building Name and grid ref Building 29 3sixty bar C4 Students’ Union 49 Department of Languages Miller 135 Job Shop (students) C4 Carrington 62 Speech and Language Therapy Psychology and Cultures C3 Clinic D6 135 Accommodation Office C4 Carrington 38 Knowledge Transfer Centre D4 Polly -

ICMA Executive Education Newsletter

Welcome to the first ICMA Stress Testing Credit Risk: The credit crunch of 1294 Executive Education newsletter The Great Depression Scenario ICMA Executive Education newsletter Issue No.1, May 2012 contents MAY 2012 INTRODUCTION PARTNERSHIPS 3 Executive education – an essential 12 IFBL & ICMA Executive Education investment in a changing market A successful five year collaboration which recently Martin Scheck, CEO of ICMA celebrated its anniversary John Board, Dean of Henley Business School 4 From the Head of ICMA Executive Education NEWS John Evans reviews ICMA’s history of education courses and looks at our current offering 13 Latest news What’s been happening recently at ICMA Executive Education COURSES FACTS & FIGURES 5 ICMA Executive Education structure How all of the ICMA Executive Education courses 14-15 Course statistics fit together Some interesting demographics about our programmes 6 Securities & Derivatives Operations A combination of two operations courses PUBLICATIONS that work particularly well together 16 Recent publications Two books published by ICMA’s trainers PEOPLE Carol Padgett and Neil Schofield 7 Featured Trainer Keith Dickinson, Programme Director for FEATURES our Operations courses shares his views 17 Stress testing credit risk 8 Training faculty Simone Varotto looks at the Great Depression scenario An introduction to all of ICMA Executive Education’s trainers 18 Back in 1294... A group of academics at the ICMA Centre examine a much earlier credit crunch CERTIFICATE HOLDERS 9 Certificate holders, 1st quarter 2012 Congratulations to all those who PROGRAMME SCHEDULE recently passed our examined courses 19 2012 schedule 10 - 11 Diploma holders See which courses we will be holding this year Meet two of our first Diploma holders ICMA Executive Education is a joint venture between ICMA and the ICMA Centre at Henley Business School, University of Reading. -

University of Reading Maps

Reading and the University C A V Halls of residence Updated August 2012. E OxfordR s S © Copyright University of Reading H Train station A M and R Bus stop R VA OA O STERN A4 A D Useful links D RO Henley AD One-way system Greenlands campu University campus maps Reading Station www.reading.ac.uk/maps I D STAT D R ION ROA HILL ON F ND ORBU LO Route information RY R E EET BLAGRAVE ST O STR N IAR A AA Route Planner FR A D L Market ’S www.theaa.com/travelwatch T T STREE Pl. IT D D BROA P U D RAC Route Planner KINGS ROAD OA 0 I K R 5 DR N E O 3 D www.route.rac.co.uk The S N 3 T KIN LO B GS T Q RO Oracle AD U S E L EENS ROAD Palmer Park TL O W Rail information S N oodley A IDR D AD ROA A C O N DO L W 3 N N O LANDS AVENUE National Rail LO E E K 2 OD O S London X IN W S A 9 O T C G A S H www.nationalrail.co.uk C R ( R A Main Entrance U RD N T M N OW Road A M Bulmershe DR O E E I T D K R A V L D ) H E R R LON E N IG 3 E H O N R A PL H RO N 2 N AD A D A M 7 o D T A Local Bus information R R R E S s R P Museum V Bulmershe E I p T I E O D R L C of English E O V D i T K A D S t N A E L a C Reading Buses N Rural Life D R O L R U L R A l AD ESCENT R PE O O S R E UE S N N D A VEN T A www.reading-buses.co.uk/university 4 BERKELEY A T R R D TO A D ING O E S D O S E AD R R E T O K H I A Airport Information L D C N ALLCR D A W OFT RD REDLA O H R R NDS R L PE IT U A UP Childs EK Heathrow Airport N Wantage NI H M4 Juncti E Hillside G C A3 St George's H www.heathrowairport.com 27 C MacKinder T 0 A3 HRIS S 5 2 on 10 TC R 3 9 HUR O (M Gatwick Airport CH R Stenton -

Postgraduate P R O G R a M M E S 2 0 2 1

POSTGRADUATE PROGRAMMES 2021/22 To make a bigger impact requires Confidence. It will shape you as a Henley graduate, along with Choice, Community, Context and Curiosity – our 5Cs. These values help us to bring business to life. 2 3 I know that you’re keen soto I’ll keep get my welcome on brief. Professor George Alexandridis, Head of Pre-experience Postgraduate Programmes. 4 5 CONFIDENCE Henley graduates have the confidence that comes from self-awareness, knowledge, reflection and applied intellect – so they feel empowered We knew to make brave decisions. that you‘d read this CURIOUS CONTEXT CHOICE COMMUNITY Henley graduates are curious, continuously They recognise the need for When they make a choice, they consider They are aware of the need for exploring new possibilities and applying this context and understand the subtle their obligations to society and the community. They network, and make thirst for knowledge to the achievement instinctive changes in approach business’ future as much as the a conscious effort to develop their of personal and organisational success. required in different situations. long-term gain. peers as well as themselves. Listen to our podcast series, ‘The unexpected Henley Live is our community Check out our courses. world of business’. for alumni and supporters. Take a look. 6 7 APPROACH TO LEARNING The Henley approach to learning is a highly respected blend of academic theory and practical application. It is designed to nurture emotionally intelligent graduates. Depending on A your chosen course, we use a -

Fallen Angels: the Investment Opportunity

Fallen Angels: The investment opportunity Authors: Prof. Andrew Clare, Prof. Stephen Thomas, Dr. Nick Motson This document is for Professional Clients only in Dubai, Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man and the UK, Professional Clients and Financial Advisers in Continental Europe and Qualifi ed Investors in Switzerland and is not for consumer use. Centre for Asset Management Research Cass Business School in cooperation with Invesco PowerShares September 2016 Table of content 1 What is a fallen angel? 3 2 What’s the potential investment opportunity? 3 - 4 2.1 The overreaction hypothesis 2.2 Institutional factors 2.3 Summary 3 Evidence of the impact on bond prices 4 - 8 4 How could investing in this idea fit into a portfolio? 8 - 10 5 Summary 10 References • Barron, M., A. Clare and S.H. Thomas, The information content of credit rating changes in the UK stock market, The Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, (1997), Vol. 24, 497-509. • Cantor, R., O. Ap Gwilym and S.H. Thomas, The Use of Credit Ratings in Investment Management in the U.S. and Europe, The Journal of Fixed Income, (Fall 2007), Vol. 17, No. 2: 13-26. • Clare, A. and S.H. Thomas, Winners and losers: UK evidence for the overreaction hypothesis, The Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, (October 1995), 961-973. • DeBondt, W.F.M. and R.H. Thaler (1985), Does the stock market overreact? Journal of Finance, Vol. 40, 793-805. • Hite, G. and A. Warga, The Effect of Bond-Rating Changes on Bond Price Performance, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. -

Engaging Engaging

Engaging businesswith Engaging with you What we stand for We empower individuals to become great business professionals and outstanding leaders who think with clarity, confidence and conviction. Our strength lies in our approach. We enable people to better understand themselves and their responsibilities while blending the practice and theories of successful business. We were established in 1945 Our most famous campus is here at Greenlands. Our campus at the University of Reading Opened in 2009. We are now celebrating our 70th anniversary Offices and campuses in 16 countries. Representatives in 29 countries From 1 management programme to a complete portfolio Bachelors Masters The degrees degrees Henley MBA Postgraduate research Executive in management education From 1 management programme to a complete portfolio Bachelors Masters The Business and degrees degrees Henley MBA Management Accounting & Information Management Real estate and planning Postgraduate research Executive Finance in management education Programmes are highly positioned in all leading rankings Example rankings for Bachelors & Masters degrees REAL ESTATE ACCOUNTING BUSINESS MASTERS IN & PLANNING – & FINANCE MANAGEMENT FINANCE LAND AND & MARKETING PROPERTY #1 #9 #9 #32 UK position for subject and UK position for subject and UK position for graduate World position for subject graduate career prospects graduate career prospects career prospects #8 in UK 94-100% student satisfaction Complete university Times/Sunday Times Guardian university Financial Times guide 2016 university -

Smart Beta: Part 2: What Lies Beneath – Cass Business School

Smart Beta: Part 2: What lies beneath? What is the evidence for smart beta? Authors: Prof. Andrew Clare, Prof. Stephen Thomas, Dr. Nick Motson This document is for Professional Clients only in Dubai, Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man and the UK, Professional Clients and Financial Advisers in Continental Europe and Qualifi ed Investors in Switzerland and is not for consumer use. Centre for Asset Management Research Cass Business School in cooperation with Invesco PowerShares November 2015 Table of content 1 Introduction 3 2 Cass’ new investment methodology 3 - 5 3 The performance of some smart beta methodologies 5 - 7 4 Bad luck or bad design 7 - 8 5 Where does the smart beta performance come from? 8 - 9 6 Conclusions 10 1. Introduction we present our results it is also worth remembering the In the first paper in this series we reviewed the difficulties that active fund managers have in beating such origins of smart beta. These origins can be found in benchmarks on a consistent basis and over the long-term1. academic research that in some cases stretches back to the 1970s. Often this research set out to test the To test our investment strategy against a Market Cap- predictions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) weighted benchmark, we put together a comprehensive and the related Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). database. We collected the end month, total returns on However, rather than confirm these predictions they all US equities quoted on the NYSE, Amex and NASDAQ ended up documenting puzzling financial market stock exchanges spanning the period from January 1964 anomalies. -

The Economics of Mutuality

OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 31/1/2021, SPi Putting Purpose Into Practice OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 31/1/2021, SPi OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 31/1/2021, SPi Putting Purpose Into Practice The Economics of Mutuality Edited by COLIN MAYER and BRUNO ROCHE 1 OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 31/1/2021, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Oxford University Press 2021 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2021 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2021930516 ISBN 978–0–19–887070–8 DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198870708.001.0001 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

ICMA Centre Announced As Top European School in Financial Trading Competition Submitted By: Pr-Sending-Enterprises Thursday, 8 April 2010

ICMA Centre announced as top European school in Financial Trading Competition Submitted by: pr-sending-enterprises Thursday, 8 April 2010 The ICMA Centre has proved that it is one of the top finance schools in the world, coming joint 4th out of a field of 44 international schools in the 2010 Rotman International Trading Competition held at the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto. This result is in line with the ICMA Centre's track record of finishing in the top 10, and usually top 5, in all previous Rotman competitions. The team of four traders - Ioannis Oikonomou, Dimitris Korovilas, Aditya Pandit and Juan Cepeda Murcia - beat a veritable who's who of corporate finance (http://www.icmacentre.ac.uk/study_and_research/msc_corporate_finance) schools to take joint fourth place. Top place went to MIT while the closest European university was Luiss University which came 30th, and the next UK school was CASS Business School which was ranked in 33rd place. The competition involved a series of different assessed cases that required trading either in an electronic environment or in the trading pit. Competitors had to trade a variety of financial instruments including corporate bonds, energy futures, stocks that were simultaneously traded in different markets, and futures on a stock index. "As recent events in world markets have shown only too clearly, skill and competence in trading and analysis are critical both to success and to survival in modern markets. This result shows that our graduates are among the best in the world and that the time and effort invested in our dealing rooms and our trading simulation software (ICTrader) was well spent - to the benefit of us and future members of the finance professions," said Dr Michael Smith, dealing room director at the ICMA Centre. -

Behavioural Finance Working Group Conference 2021

Behavioural Finance Working Group Conference 2021 qmul.ac.uk/busman Theme: Behavioural Finance and Ethics Date Thursday 10- Friday 11 June 2021 Venue Zoom Keynote Speakers Professor Max Bazerman (Harvard Business School) and Professor Boudewijn de Bruin (University of Groningen) Special Issue Review of Behavioural Finance Best Paper Awards Best Quantitative Paper Award: Review of Behavioural Finance Best Qualitative Paper Award: Qualitative Research in Financial Markets PhD Student Funding: ICAEW’s Charitable Trusts Organisers Gulnur Muradoglu (Queen Mary University of London) Daphne Sobolev (University College London, UK) 2 qmul.ac.uk Conference Programme At A Glance Day 1 - Thursday 10 June 8:50-9:00 Welcome to BFWG 2021 9:00-10:30 1. Financial 2. Attention 3. Individual 4. Market Sessions 1-4 ethics, crime and effects I differences I: behaviour regulation I: SR Personality effects 10:30-11:00 Coffee Break 11:00-12:30 5. Financial 6. Attention 7. Individual 8. Sentiment and Sessions 5-8 ethics, crime effects II differences II: emotion I and regulation II: Gender effects Fintech and ethics 12:30-13:30 Lunch 13:30-15:00 9. Financial 10. Policies and 11. Individual 12. Sentiment and Sessions ethics, crime and contracts differences III: emotion II 9-12 regulation III: Culture effects Unethical conduct and crime 15:00-15:30 Coffee Break 15:30-17:00 13. Herding and 14. Behavioural 15 Learning 16. Trading in Sessions momentum biases and difficult times 13-16 trading anomalies 17:00-18:00 Keynote Speech by Max Bazerman Day 2 - Friday 11 June 9:00-10:30 17.