Marxist Utopia and Political Idealism in the Poetry of Pablo Neruda and Faiz Ahmad Faiz: a Comparative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Concept of the Perfect Man in the Thought of Ibn 'Arabiand Muhammad Iqbal: a Comparative Study

THE CONCEPT OF THE PERFECT MAN IN THE THOUGHT OF IBN 'ARABIAND MUHAMMAD IQBAL: A COMPARATIVE STUDY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate St udies and Research in partial fulfîllment of the requiremeat for the degree of Mast er of Arts Institut e of Islamic St udies Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research McGill University Mont real May 1997 National Library Bibliothbque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OnaiwaON K1AW CNtawaON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microforni, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Author : Iskandar Amel Tit le : "The Concept of the Perfect Man in the Thought of Ibn '~rabiand Muhammad Iqbal: A Comparative Study" Department : Inst it ute of Islamic St udies, McGill University, Montreal, Canada Degree : Master of Arts (M.A.) This thesis deals with the concept of the Pcrfect Man in the thought of both Ibn '~rabi(%O/ 1 165-63811 240) and Iqbal ( 1877- 1938). -

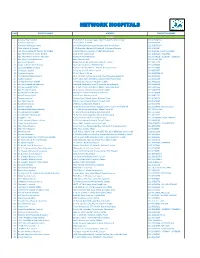

Network Hospitals

NETWORK HOSPITALS S.NO HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBERS KARACHI 1 Adamjee Eye Hospital 39-B, Block C, Adamjee Nagar, Opp. Zubaida Hospital, Dhoraji 021-34132824-6 2 Advanced Eye Clinic 17-C/1, Block 6, PECHS 021-34540999 3 Advanced Radiology Centre Behind Hamdard University Hospital, M.A. Jinnah Road 021-32783535-6 4 Afsar Memorial Hospital B-35 Khalid Bin Waleed Rd, Sector W, Gulshan-e-Maymar 021-36353124 5 Aga Khan Hospital for Women Karimabad Ayesha Manzil, at junction of Shahrah-e-Pakistan 021-3682296-3 / 021-33100006 6 Aga Khan Maternity Home Garden Gold Street, Garden East 021-33100005 / 32256903 7 Aga Khan Maternity Home Kharadar Atmaram Pritamdas Road 021-32524618 / 32542187 / 33100007 8 Aga Khan University Hospital Main Stadium Road 021 111-911-911 9 Akhter Eye Hospital Rashid Minhas Rd, 4/C Block 5 Gulshan-e-Iqbal 021-34811979 10 Al Ain Institute of Eye Disease Shahrah-e-Quaideen, PECHS Block 2 021-34556460 11 Al Hadeed Medical Centre Gulshan e Hadeed Phase 1 Phase 1 Bin Qasim Town 021-34713800 12 Al Rayyaz Hospital St-24, Sector 11/B, North Karachi 021-36907697 13 Altamash Hospital ST 9A / Block 1, Clifton 021-35187000-16 14 Arif Defence Medical Centre DK-1, Off 34th Commercial Street, Main Khayaban-e-Bukhari 021-35155631 15 Asghar Hospital KDA Market, KDA roundabout, Block B North Nazimabad 021-36642389 16 Ashfaq Memorial Hospital University Rd, Block 13 C Gulshan-e-Iqbal 021-34822261 17 Asif Eye Hospital Bahadarabad Westland Apartment, Ismail Chowrangi, Bahadurabad 021-34944530 18 Asif Eye Hospital Clifton 65-C, 24th Commercial Street, Phase II Extension, DHA 021-35385166 19 Atia General Hospital 48-A, Darakhshan Society, Kala Board, Malir 021-34400726 20 Ayesha General Hospital Gulshan-e- Hadeed C-50 Phase -3 Side Rd 021 34716608 21 Azam Town Hospital Azam Town, Mehmoodabad 021-35801741 22 Banaras Hospital Banaras Bazar Chowk, Sector 8 Orangi Town, 021-34150416 23 Bay View Hospital 205 A-ll, Saba Avenue, Zone A Phase 8, DHA 021-35246225 24 Boulevard Hospital 17th East Street, D.H.A. -

Ishrat Afreen - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Ishrat Afreen - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Ishrat Afreen(25 December 1956) Ishrat Afreen (Urdu: ???? ?????; Hindi: ???? ?????; alternative spelling: Ishrat Aafreen; born December 25, 1956) is an Urdu poet and women's rights activist named one of the five most influential and trend-setting female voices in Urdu Literature. Her works have been translated in many languages including English, Japanese, Sanskrit and Hindi. The renowned ghazal singers Jagjit Singh & Chitra Singh also performed her poetry in their anthology, Beyond Time (1987). Famed actor Zia Mohyeddin also recites her nazms in his 17th and 20th volumes as well as his ongoing concerts. <b> Early Life and Career </b> Ishrat Jehan was born into an educated family in Karachi, Pakistan as the oldest of five children. She later took the pen name Ishrat Afreen. She was first published at the age of 14 in the Daily Jang on April 31, 1971. She continued writing and was published in a multitude of literary magazines across the subcontinent of India and Pakistan. She eventually became assistant editor for the monthly magazine Awaaz, edited by the poet Fahmida Riaz. Parallel to her writing career she participated in several radio shows on Radio Pakistan from 1970-1984 that aired nationally and globally. She later worked under Mirza Jamil on the now universal Noori Nastaliq Urdu script for InPage. She married Syed Perwaiz Jafri, an Indian lawyer, in 1985 and migrated to India. Five years thereafter, the couple and their two children migrated to America. They now reside in Houston, Texas with their three children. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed/Peer-Reviewed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 6.292 (SJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 6.292 (SJIF) Intersection of Poetry and Politics: A Comparative Study Between the Life and Poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Pablo Neruda Suhail Mohammed Student, MA (English) Final Year Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. Abstract Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911-1984) was a famous revolutionary Pakistani poet who wrote chiefly in Urdu and Punjabi. He is known all over the world for his romantic as well as hard hitting poems and nazms. His “poetry with purpose” is sung and read even today to shatter the chains of oppression and hegemony. Pablo Neruda (1904-1973), on the other hand was a well-known Chilean poet and writer. Neruda wrote on a variety of subjects since his tender age and like Faiz, his poems are too tools of intellectual resistance. His poems have too transcended geographical boundaries in equal pace like that of Faiz. Both Faiz and Neruda were friends and had a good rapport. Their poems have been praised not only in their homelands but across territories and won global acceptance. The paper attempts to bring out the commonality between the life and poetry of Faiz and Neruda. The paper also attempts to analyse how their poems were anti- colonialist and anti-fascism. Keywords: revolutionary, oppression, hegemony, anti-colonialist, intellectual resistance Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Pablo Neruda were contemporary poets and friends whose poems have ever been tools of intellectual resistance. Their works show major similarities with both being anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist and they both denounced oppressions not only in their homelands but all across the globe in any form. -

Hafeez Jalandhari - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Hafeez Jalandhari - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Hafeez Jalandhari(14 January 1900 - 21 December 1982) Abu-Al-Asar Hafeez Jalandhari (Urdu: ??? ????? ???? ????????) Pakistani writer, poet and, above all, composer of the National Anthem of Pakistan. He was born in Jalandhar, Punjab, British India on January 14, 1900. After independence of Pakistan in 1947, Hafeez Jalandhari moved to Lahore. Hafeez made up for the lack of formal education with self-study but he has the privilege to have some advise from the great Persian poet Maulana Ghulam Qadir Bilgrami. His dedication, hard work and advise from such a learned person carved his place in poetic pantheon. Hafeez Jalandhari actively participated in Pakistan Movement and used his writings to propagate for the cause of Pakistan. In early 1948, he joined the forces for the freedom of Kashmir and got wounded. Hafeez Jalandhari wrote the Kashmiri Anthem, "Watan Hamara Azad Kashmir". He wrote many patriotic songs during Pakistan, India war in 1965. Hafeez Jalandhari served as Director General of morals in Pakistan Armed Forces, and very prominent position as adviser to the President, Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan and also Director of Writer's Guild. Hafeez Jalandhari's monumental work of poetry, Shahnam-e-Islam, gave him incredible fame which, in the manner of Firdowsi's Shahnameh, is a record of the glorious history of Islam in verse. Hafeez Jalandhari wrote the national anthem of Pakistan composed by Ahmed Ghulamali Chagla also known as Ahmed G Chagla. He is unique in Urdu poetry for the enchanting melody of his voice and lilting rhythms of his songs and lyrics. -

![South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal , Free-Standing Articles the Left Radical of Afghanistan [Chap-E Radikal-E Afghanistan]: Finding Trots](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8182/south-asia-multidisciplinary-academic-journal-free-standing-articles-the-left-radical-of-afghanistan-chap-e-radikal-e-afghanistan-finding-trots-348182.webp)

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal , Free-Standing Articles the Left Radical of Afghanistan [Chap-E Radikal-E Afghanistan]: Finding Trots

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Free-Standing Articles | 2015 The Left Radical of Afghanistan [Chap-e Radikal-e Afghanistan]: Finding Trotsky after Stalin and Mao? Darren Atkinson Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3895 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.3895 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Darren Atkinson, “The Left Radical of Afghanistan [Chap-e Radikal-e Afghanistan]: Finding Trotsky after Stalin and Mao?”, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], Free-Standing Articles, Online since 02 June 2015, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/ 3895 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.3895 This text was automatically generated on 21 September 2021. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The Left Radical of Afghanistan [Chap-e Radikal-e Afghanistan]: Finding Trots... 1 The Left Radical of Afghanistan [ Chap-e Radikal-e Afghanistan]: Finding Trotsky after Stalin and Mao? Darren Atkinson Introduction: why examine the Left Radical of Afghanistan? 1 For many analysts of Afghanistan, the importance of leftist political ideology came to an end with the reformulation of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) [Hezb- e Demokratic-e Khalq-e Afghanistan], the ostensibly communist party of government, as the Homeland Party of Afghanistan [Hezb-e-Watan-e Afghanistan] in 1987.1 This event, along with removal of Soviet troops in 1989, the ouster of President Najibullah’s in 1992, and his eventual execution in 1996, has meant that Afghanistan’s political development has tended to be analysed in relation to the success and failures of the Mujahedeen, the rise, fall and rise of the Taleban and the implications of US and NATO intervention and occupation. -

Kakaji Sanobar Hussain Mohmand an Everlasting Personality

TAKATOOT Issue 5Volume 3 20 January - June 2011 Kakaji Sanobar Hussain Mohmand An Everlasting Personality Dr. Hanif Khalil Abstract: Kakaji Sanobar Hussain Mohmand was a renowned intellectual and politician of the sub-continent among the pashtoon celebrities. He was a poet, critic, researcher, Journalist and translator of Pashto literature at a time. Apart from this he was a practical politician and a freedom fighter. Kakaji Sanobar played a vital role in the reawakening of the pashtoons as well as the other minorities against the British imperialism and the cruel and unjust policies of the Britishers in the sub continent. He used his journalistic abilities and his journal the monthly Aslam as well as his writings in prose and verses for achieving the targets to his real mission. For the fulfillment of this purpose he remained in jails for several years. He gave a lot of sacrifices, faces many hurdles and difficulties, but no one could remove him from his firm determination. In this paper the author has elaborated the major achievements and surveyed the practical steps and sacrifices of this legendary personality of the 20 th century. This paper is actually a tribute to Kakaji Sanobar Hussain the stalwart personality of pashtoon nation . I declare, that among the genius personalities of Pashtun nation, after khushal Khan Khattak, Kakaji Sanobar Hussain is a personality which could be accepted as a multi-dimensional celebrity. For the acceptance of that declaration, I would say that Kakaji was not only a great man but also a great Politician, Writer, Journalist and a Social Worker simultaneously. -

Poems of Faiz Ahmad Faiz: a Poet of the Third World, Faizðœâ¤ AбÑ'ò

Poems of Faiz Ahmad Faiz: A Poet of the Third World, FaizМ¤ Aбёҕmad FaizМ¤, M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd., 1995, 8185880670, 9788185880679, . The poetry if Faiz Ahmad Faiz, the most acclimed modern urdu poet, shows how a soft mellowed diction can effectively depict the intense feelings of a hard core pre-perestroika activist of international repute. The translations bear out the softness as well as the poignancy of the original. Retention of the original imagery and idiom adds up to a new expressional hue in English.. DOWNLOAD http://archbd.net/18iGbeR MutМ¤ДЃlaК»ah-yi FaizМ¤, YЕ«rap menМІ , AshfДЃq бё¤usain, 1994, Poets, Urdu, 542 pages. On the life and works of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, 1911-1984, Urdu poet, during his visits to Europe; contributed articles. The Rebel's Silhouette Selected Poems, FaizМ¤ Aбёҕmad FaizМ¤, 1991, Poetry, 102 pages. Born in India and considered the leading poet on the South Asian subcontinent, Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911-1984) was a two-time Nobel nominee and winner of the 1962 Lenin Peace Prize .... Over My Shoulder , Alys Faiz, 1993, History, 448 pages. Autobiography of the widow of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, a noted Pakistani poet. Includes some poems by Alys Faiz.. MutМ¤ДЃlaК»ah-yi FaizМ¤, AmrД«kah va KanД«бёЌДЃ menМІ , AshfДЃq бё¤usain, 1994, Poets, Urdu, 511 pages. On the life and works of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, 1911-1984, Urdu poet during his visits to America and Canada. Mire dil mire musДЃfir , FaizМ¤ Aбёҕmad FaizМ¤, 1981, Urdu poetry, 93 pages. -

1St Merit List Open Candidates (Emergency Radio RT Dialysis).Pdf

1ST MERIT LIST OF OPEN CANDIDATES (DIALYSIS) DISCIPLINE SESSION 2020 DURAN PUR CAMPUS SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES ARE REQUIRED TO APPEAR BEFORE THE ADMISSION COMMITTEE ALONG WITH ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS ON 09 DECEMBER, 2020 AT 09:00 AM, IN THE OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR, KMU-IPMS, DURANPUR, PESHAWAR, POSITIVELY. Errors & omissions are subject to subsequent ractification s# (10%) (50%) (40%) Name Marks Obtain MARKS MARKS Domicile (M/D/Y) SSC Total REMARKS Entry Test Entry Test HSSC Total SSC Obtain HSSC %age IMPROVED Merit Merit Score %age Marks HSSC Obtain HSSC Obtain Passing Year Passing Year Passing Date of Date Birth of Gender (M/F) Gender Father's Name Father's SCC weightage Weightage Test Weightage Adjusted Marks Adjusted Entry Test Total Weightage HSSC Weightage SSC % age Marks SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 1 Areeba Mukhtar Mukhtar Hussain F 9/17/2000 Mansehra 1009 1100 2017 91.73 932 1100 2019 932 84.73 81 100 81.00 9.17 42.36 32.4 83.94 SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 2 Waqas khan Khaliq dad khan M 1/8/2002 Swat 946 1100 2018 86.00 944 1100 2020 944 85.82 80 100 80.00 8.60 42.91 32 83.51 SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 3 Salman Ahmad Abdul Hamid M 3/6/1999 Swat 952 1100 2015 86.55 939 1100 2018 929 84.45 81 100 81.00 8.65 42.23 32.4 83.28 MI SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 4 Muhammad Arsalan Azam Rizwan Ullah M 3/4/2002 Charsadda 1030 1100 2017 93.64 930 1100 2019 930 84.55 78 100 78.00 9.36 42.27 31.2 82.84 SHORTLISTED FOR INTERVIEW 5 Abdul Haseeb Khatak Farman Ullah M 11/4/2000 Peshawar 1006 1100 2017 91.45 937 1100 2020 927 84.27 78 100 78.00 9.15 42.14 31.2 -

Annual Review Research Community Are Invited to Participate, Exchange Ideas and Network in Our Regular Workshops, Lectures and Conferences

Join the SOAS South Asia Institute The SOAS South Asia Institute welcomes people with an interest in South Asia who would like to get involved with our activities. Our offices are located on the 4th floor of the Brunei Gallery and we welcome visitors by appointment. There are many ways of getting involved with the SSAI: Connect with Us: • Study at SOAS: The SSAI has developed a new Email: Receive regular updates from us about events Masters programme in Intensive South Asian Studies. and activities by writing to [email protected] This two-year programme offers comprehensive language-based training across a wide range of Like us on Facebook and join our vibrant disciplines in the humanities and social sciences. community: www.facebook.com/SouthAsia.SOAS All of the Institute’s teaching programmes will provide students with valuable skills that are rarely Follow and interact with us on Twitter: @soas_sai available elsewhere. These include interdisciplinary understandings of South Asian society that are Check our web pages for details about all our theoretically sophisticated and based on deep activities: www.soas.ac.uk/south-asia-institute/ empirical foundations and advanced proficiency in Join in the discussion through the languages such as Bengali, Hindi, Nepali, Sanskrit and Institute’s new blog, South Asia Notes: Urdu. http://blogs.soas.ac.uk/ssai-notes/ • Outreach: Our free seminar series, which is held regularly on a weekly or fortnightly basis is open to Address: the wider public. Our events often host high-level The SOAS South Asia Institute politicians, local and foreign academics and many Room B405, Brunei Gallery SOAS SOUTH ASIA INSTITUTE more. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae ARSHAD MASOOD HASHMI Associate Professor, Department of Urdu Gopeshwar College, Gopalganj, 841436, India Contact:91-9934502098 [email protected] EDUCATION B.R.A. BIHAR UNIVERSITY, Muzaffarpur, India D.Lit. in Urdu, April’ 2002 Topic of Thesis: Premchand aur Lu Xun kay Fun ka Taqaabli Motalea B.R.A. BIHAR UNIVERSITY, Muzaffarpur, India Ph.D. in Urdu, August’ 1997 Topic of Ph.D. Thesis: Nafsi Tajarbe aur Adabi Takhleeq UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISION, New Delhi, India National Eligibility Test for Lectureship, June’ 1994 B.R.A. BIHAR UNIVERSITY, Muzaffarpur, India M. A. In Urdu Literature, June’ 1994 L. N. MITHILA UNIVERSITY, Darbhanga, India M. A. In English Literature, April’ 1992 B.R.A. BIHAR UNIVERSITY, Muzaffarpur, India B. A. (Honours) in English Literature, July’ 1989 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Department of Urdu, Gopeshwar College, Gopalganj (Jai Prakash University, Chapra, India) Associate Professor, September’ 2008 to present Page 1 of 14 * Teaching History of Urdu language & literature, criticism, classical and modern poetry, drama, Fiction and History of Islam to graduate classes * Designed series of teaching resources for students to develop the skills of critical thinking, ethical conduct, problem-solving, discussion in groups, team building and academic writing P.G. Department of Urdu, Jai Prakash University, Chapra, India Associate Professor, December’ 2006 – August’ 2008 * Taught History of Hindi Literature and linguistics to post-graduate students *Used modern pedagogies to teach modern and practical criticism -

The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://hse.hipatiapress.com The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan Muhammad Anwar Farooq1 1) The Islamia University of Bahawalpur (Pakistan) Date of publication: October 23rd, 2017 Edition period: Edition period: October 2017-February 2018 To cite this article: Farooq, M.A. (2017). The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan [Review of the book]. Social and Education History 6(3), 342-345. doi: 10.17583/hse.2017.2485 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.17583/hse.2017.2485 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). HSE – Social and Education History Vol. 6 No. 3 October 2017 pp. 342-345 Reviews (I) Saadia, T. (2014). The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan Karachi. Oxford: Oxford University Press. he content of a book is always a reflection of mind of the author about an issue but on the other hand it also provides a candid story T of topic under discussion. The complexity in the genetic makeup of Pakistan is undeniable in all respects like religious, political, cultural and social. But the causes of such complexity are still vague and modern scholarship on Pakistan Studies is just about to identify and explore the relationship between religious, political, cultural and social variables. Many scholars tried to explore such relationship and the outcomes of the process appeared as a cloud of opinions on the same issue.