Abstract out of the Ashes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'opéra Moby Dick De Jake Heggie

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 20 | 2020 Staging American Nights L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour l’œuvre d’Herman Melville Nathalie Massoulier Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/26739 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.26739 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Nathalie Massoulier, « L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour l’œuvre d’Herman Melville », Miranda [En ligne], 20 | 2020, mis en ligne le 20 avril 2020, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/26739 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ miranda.26739 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour ... 1 L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour l’œuvre d’Herman Melville Nathalie Massoulier Le moment où une situation mythologique réapparaît est toujours caractérisé par une intensité émotionnelle spéciale : tout se passe comme si quelque chose résonnait en nous qui n’avait jamais résonné auparavant ou comme si certaines forces demeurées jusque-là insoupçonnées se mettaient à se déchaîner […], en de tels moments, nous n’agissons plus en tant qu’individus mais en tant que race, c’est la voix de l’humanité tout entière qui se fait entendre en nous, […] une voix plus puissante que la nôtre propre est invoquée. -

Riders of the Purple Sage, Arizona Opera February & March 2017 As

Riders of the Purple Sage, Arizona Opera February & March 2017 As her helper, the gunslinger Lassiter, Morgan Smith gave us a stunning performance of a role in which the character’s personality gradually unfolds and grows in complexity. Maria Nockin, Opera Today, 7 March 2017 On opening night in Tucson, the lead roles of Jane and Lassiter were sung by soprano Karin Wolverton and baritone Morgan Smith, who both deliver memorable arias. Smith plays Lassiter with vintage Clint Eastwood menace as he growls out his provocative maxim, “A man without a gun is only half a man.” Kerry Lengel, Arizona Republic, 27 February 2017 Moby-Dick, Dallas Opera November 2016 Morgan Smith brings a dense, dark baritone to the role of Starbuck, the ship's voice of reason Scott Cantrell, Dallas News, 5 November 2016 Morgan Smith, who played Starbuck, gave a stunningly powerful performance in this scene, making the internal conflict in the character believable and real. Keith Cerny, Theater Jones, 6 December 2016 First Mate Starbuck is again sung by baritone Morgan Smith, who offers convincing muscularity and authority. J. Robin Coffelt, Texas Classical Review, 6 November 2016 Morgan Smith finely acted in the role of second in command, Starbuck, and his singing was even finer. When Starbuck attempts to dissuade Captain Ahab from his fool’s mission to wreck vengeance on the white whale, the audience was treated to the evening's most powerful and passionate singing — his duets with tenor Jay Hunter Morris as Ahab in particular. Monica Smart, Dallas Observer, 8 November 2016 Madama Butterfly, Kentucky Opera September 2016 With a diplomatic air and a rich, velvety baritone, he upheld the title of Consul and caretaker in a fatherly way. -

SMALL CRIMES DIAS News from PLANET MARS ALL of a SUDDEN

2016 IN CannES NEW ANNOUNCEMENTS UPCOMING ALSO AVAILABLE CONTACT IN CANNES NEW Slack BAY SMALL CRIMES CALL ME BY YOUR NAME NEWS FROM NEW OFFICE by Bruno Dumont by E.L. Katz by Luca Guadagnino planet mars th Official Selection – In Competition In Pre Production In Pre Production by Dominik Moll 84 RUE D’ANTIBES, 4 FLOOR 06400 CANNES - FRANCE THE SALESMAN DIAS NEW MR. STEIN GOES ONLINE ALL OF A SUDDEN EMILIE GEORGES (May 10th - 22nd) by Asghar Farhadi by Jonathan English by Stephane Robelin by Asli Özge Official Selection – In Competition In Pre Production In Pre Production [email protected] / +33 6 62 08 83 43 TANJA MEISSNER (May 11th - 22nd) GIRL ASLEEP THE MIDWIFE [email protected] / +33 6 22 92 48 31 by Martin Provost by Rosemary Myers AN ArtsCOPE FILM NICHolas Kaiser (May 10th - 22nd) In Production [email protected] / +33 6 43 44 48 99 BERLIN SYNDROME MatHIEU DelaUNAY (May 10th - 22nd) by Cate Shortland [email protected] / + 33 6 87 88 45 26 In Post Production Sata CissokHO (May 10th - 22nd) [email protected] / +33 6 17 70 35 82 THE DARKNESS design: www.clade.fr / Graphic non contractual Credits by Daniel Castro Zimbrón Naima ABED (May 12th - 20th) OFFICE IN PARIS MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL In Post Production [email protected] / +44 7731 611 461 9 Cité Paradis – 75010 Paris – France Tel: +33 1 53 34 90 20 | Fax: +33 1 42 47 11 24 [email protected] [email protected] Proudly sponsored by www.memento-films.com | Follow us on Facebook NEW OFFICE IN CANNES 84 RUE D’ANTIBES, 4th FLOOR -

Westminsterresearch the Artist Biopic

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The artist biopic: a historical analysis of narrative cinema, 1934- 2010 Bovey, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr David Bovey, 2015. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 THE ARTIST BIOPIC: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NARRATIVE CINEMA, 1934-2010 DAVID ALLAN BOVEY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Master of Philosophy December 2015 2 ABSTRACT The thesis provides an historical overview of the artist biopic that has emerged as a distinct sub-genre of the biopic as a whole, totalling some ninety films from Europe and America alone since the first talking artist biopic in 1934. Their making usually reflects a determination on the part of the director or star to see the artist as an alter-ego. Many of them were adaptations of successful literary works, which tempted financial backers by having a ready-made audience based on a pre-established reputation. The sub-genre’s development is explored via the grouping of films with associated themes and the use of case studies. -

Who's Who at the Rodin Museum

WHO’S WHO AT THE RODIN MUSEUM Within the Rodin Museum is a large collection of bronzes and plaster studies representing an array of tremendously engaging people ranging from leading literary and political figures to the unknown French handyman whose misshapen proboscis was immortalized by the sculptor. Here is a glimpse at some of the most famous residents of the Museum… ROSE BEURET At the age of 24 Rodin met Rose Beuret, a seamstress who would become his life-long companion and the mother of his son. She was Rodin’s lover, housekeeper and studio helper, modeling for many of his works. Mignon, a particularly vivacious portrait, represents Rose at the age of 25 or 26; Mask of Mme Rodin depicts her at 40. Rose was not the only lover in Rodin's life. Some have speculated the raging expression on the face of the winged female warrior in The Call to Arms was based on Rose during a moment of jealous rage. Rose would not leave Rodin, despite his many relationships with other women. When they finally married, Rodin, 76, and Rose, 72, were both very ill. She died two weeks later of pneumonia, and Rodin passed away ten months later. The two Mignon, Auguste Rodin, 1867-68. Bronze, 15 ½ x 12 x 9 ½ “. were buried in a tomb dominated by what is probably the best The Rodin Museum, Philadelphia. known of all Rodin creations, The Thinker. The entrance to Gift of Jules E. Mastbaum. the Rodin Museum is based on their tomb. CAMILLE CLAUDEL The relationship between Rodin and sculptor Camille Claudel has been fodder for speculation and drama since the turn of the twentieth century. -

Three Decembers” STARRING WORLD-RENOWNED MEZZO SOPRANO SUSAN GRAHAM and CELEBRATED ARTISTS MAYA KHERANI and EFRAÍN SOLÍS Available Via Online Streaming Anytime

OPERA SAN JOSÉ EXTENDS ACCESS TO VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE OF Jake Heggie’s “Three Decembers” STARRING WORLD-RENOWNED MEZZO SOPRANO SUSAN GRAHAM AND CELEBRATED ARTISTS MAYA KHERANI AND EFRAÍN SOLÍS Available via online streaming anytime SAN JOSE, CA (3 February 2021) – In keeping with Opera San José’s mission to expand accessibility to its work, the company has announced that through the support of generous donors it is able to extend access to its hit virtual production of Jake Heggie’s chamber opera, Three Decembers, now making it available on a pay-what-you-can basis for streaming on demand. The production is being offered with subtitles in Spanish and Vietnamese, as well as English, furthering its accessibility to the Spanish and Vietnamese speaking members of the San Jose community, two of the largest populations in its home region. Featuring world-renowned mezzo-soprano Susan Graham in the central role, alongside celebrated Opera San José Resident Artists soprano Maya Kherani and baritone Efraín Solís, this world-class digital production has been met with widespread critical acclaim. Based on an unpublished play by Tony Award winning playwright Terrence McNally, Three Decembers follows the riveting story of a famous stage actress and her two adult children, struggling to connect over three decades, as long-held secrets come to light. With a brilliant, witty libretto by Gene Scheer and a soaring musical score by Jake Heggie, Three Decembers offers a 90-minute fullhearted American opera about family – the ones we are born into and those we create. Tickets for the modern work, which was recorded last Fall in the company’s Heiman Digital Media Studio, are pay-what-you-can beginning at $15 per household, which includes on-demand streaming for 30 days after date of purchase. -

Rodin Biography

Contact: Norman Keyes, Jr., Director of Media Relations Frank Luzi, Press Officer (215) 684-7864 [email protected] AUGUSTE RODIN’S LIFE AND WORK François-Auguste-René Rodin was born in Paris in 1840. By the time he died in 1917, he was not only the most celebrated sculptor in France, but also one of the most famous artists in the world. Rodin rewrote the rules of what was possible in sculpture. Controversial and celebrated during his lifetime, Rodin broke new ground with vigorous sculptures of the human form that often convey great drama and pathos. For him, beauty existed in the truthful representation of inner states, and to this end he often subtly distorted anatomy. His genius provided inspiration for a host of successors such as Henri Matisse, Constantin Brancusi and Henry Moore. Unlike contemporary Impressionist Paul Cézanne---whose work was more revered after his death---Rodin enjoyed fame as a living artist. He saw a room in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York dedicated to his work and willed his townhouse in Paris, the Hôtel Biron, to the state as a last memorial to himself. But he was also the subject of intense debate over the merits of his art, and in 1898 he attracted a storm of controversy for his unconventional monument to French literary icon Honoré de Balzac. MAJOR EVENTS IN RODIN’S LIFE 1840 November 12. Rodin is born in Paris. 1854 Enters La Petite École, a special school for drawing and mathematics. 1857 Fails in three attempts to be admitted at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. -

Es Un Proyecto De

ES UN PROYECTO DE: festivalcinesevilla.eu Es un proyecto de: Alcalde de Sevilla Presidente del ICAS Juan Ignacio Zoido Álvarez Teniente Alcalde Delegada de Cultura, Educación, Deportes y Juventud Vicepresidenta del ICAS María del Mar Sánchez Estrella Directora General de Cultura María Eugenia Candil Cano Director del Festival de Cine Europeo de Sevilla José Luis Cienfuegos PROGRAMA DE MANO Edición y textos: Elena Duque Documentación: Antonio Abad Textos música: Tali Carreto Diseño e impresión: Avante de Publicidad (www.avantedepublicidad.com) Maquetación: Páginas del Sur UNA PUBLICACIÓN DEL ICAS Instituto de la Cultura y de las Artes de Sevillla Depósito Legal: SE 2038-2013 PRESENTACIÓN SECCIÓN OFICIAL 5 Las obras clave del 2013, el mejor cine europeo reconocido internacionalmente. LAS NUEVAS OLAS (FICCIÓN+NO FICCIÓN) 15 Los nuevos valores y las miradas singulares del cine europeo contemporáneo más refrescante. RESISTENCIAS 29 Cine español estimulante y combativo, producciones independientes que plantan cara a la crisis con ímpetu creativo. SELECCIÓN EFA 35 Las películas prenominadas a los premios de la European Film Academy, MARÍA DEL MAR SÁNCHEZ ESTRELLA sello de calidad indiscutible. TENIENTE ALCALDE DELEGADA DE CULTURA, EDUCACIÓN, DEPORTES Y JUVENTUD VICEPRESIDENta DEL ICAS SPECIAL SCREENING 43 Proyecciones especiales que acercan a Sevilla películas imperdibles. Hablar de Sevilla en otoño es hacerlo de cine europeo. De audacia SEFF PARA TODA LA FAMILIA 47 creativa, de tradición y de futuro, de apuesta por el talento y de Cine para pequeños y mayores, una selección de lo mejor del cine familiar europeo. comunión entre los sevillanos y sus espacios culturales. Y es así SEFF JOVEN 51 porque el Festival de Cine Europeo ha conseguido lo que el Ayun- El ritmo, el ardor y la fuerza de los años del frescor. -

Lo Sguardo (Dis)Umano Di Bruno Dumont

Lo sguardo (dis)umano di Bruno Dumont Alberto Scandola «La cinematografia – ha dichiarato Bruno Dumont – è disumana. […] È la materia delle nostre vite, è la vita stessa, presente e rappresentata»1. Sin dagli esordi (L’età inquieta, 1997), Bruno Dumont ha posto al centro della sua attenzione l’umano e soprattutto le sue derive verso l’animale, il selvaggio, il bestiale. Liberi di non significare altro che loro stessi e il loro opaco Dasein, i corpi di questo cinema abitano luoghi dove – penso a L’humanité (1999) – il visibile altro non è che il riflesso dell’invisibile e l’immagine sembra lottare contro il suono. Conflitti come quello tra i volumi e i rumori (l’ansimare dettagliato di un corpo ripreso in campo lunghissimo, per esempio), frequenti soprattutto nella prima fase della produzione, sono finalizzati a evidenziare la testura di un dispositivo a cui l’autore da sempre affida una precisa funziona catartica: Bisogna sviluppare il sistema immunitario dello spettatore, biso- gna mettergli il male. Costui svilupperà naturalmente gli anticorpi. È lo spettatore che deve svegliarsi, non il film. Per me un film non è molto importante. Ciò che è importante è cominciare; poi tocca allo spettatore terminare2. Per poter «terminare», però, bisogna innanzitutto riuscire a guardare. Guardare immagini che, nel disperato tentativo di catturare le vita, offrono 1 B. Dumont in Ph. Tancelin, S. Ors, V. Jouve, Bruno Dumont, Éditions Dis Voir, Paris 2001, p. 12. Nostra traduzione. 2 B. Dumont in A. Scandola, Un’estetica della rivelazione. Conversazione con Bruno Du- mont, in Schermi D’Amore dieci+1, a cura di P. -

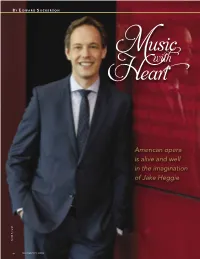

Music with Heart.Pdf

Wonderful Life 2018 insert.qxp_IAWL 2018 11/5/18 8:07 PM Page 1 B Y E DWARD S ECKERSON usic M with Heart American opera is alive and well in the imagination of Jake Heggie LMOND A AREN K 40 SAN FRANCISCO OPERA Wonderful Life 2018 insert.qxp_IAWL 2018 11/5/18 8:07 PM Page 2 n the multifaceted world of music theater, opera has true only to himself and that his unapologetic fondness for and always occupied the higher ground. It’s almost as if love of the American stage at its most lyric would dictate how he the very word has served to elevate the form and would write, in the only way he knew how: tonally, gratefully, gen- willfully set it apart from that branch of the genre where characters erously, from the heart. are wont to speak as well as sing: the musical. But where does Dissenting voices have accused him of not pushing the enve- thatI leave Bizet’s Carmen or Mozart’s Magic Flute? And why is it lope, of rejoicing in the past and not the future, of veering too so hard to accept that music theater comes in a great many forms close to Broadway (as if that were a bad thing) and courting popu- and styles and that through-sung or not, there are stories to be lar appeal. But where Bernstein, it could be argued, spent too told in words and music and more than one way to tell them? Will much precious time quietly seeking the approval of his cutting- there ever be an end to the tedious debate as to whether Stephen edge contemporaries (with even a work like A Quiet Place betray- Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd or Leonard Bernstein’s Candide are ing a certain determination to toughen up his act), Heggie has musicals or operas? Both scores are inherently “operatic” for written only the music he wanted—needed—to write. -

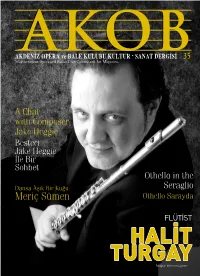

An Interview with Jake Heggie

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

SF Opera Guild Virtual Event April 28.Pdf

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA GUILD PRESENTS “LIFE. CHANGING. AN EVENING WITH FREDERICA VON STADE & JAKE HEGGIE,” APRIL 28 Frederica von Stade; Jake Heggie (photo: Karen Almond); Gasia Mikaelian SAN FRANCISCO, CA (April 21, 2021) — San Francisco Opera Guild will present a complimentary virtual livestream event Life. Changing. An Evening with Frederica von Stade & Jake Heggie on Wednesday, April 28 at 6 pm Pacific. Mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade (“Flicka”), American composer Jake Heggie and San Francisco Opera Guild students, alumni and teachers will share inspiring stories and uplifting songs, while celebrating music’s power to change lives. The event includes an intimate Q&A that will give attendees the chance to ask Flicka and Jake questions. KTVU Mornings on 2 news anchor and longtime opera enthusiast Gasia Mikaelian will serve as emcee. Life. Changing. is open to the public; complimentary advance registration required: give.sfoperaguild.com/LifeChanging. 1 Frederica von Stade said: “I love being with my pal, the wonderful Jake Heggie, to celebrate the great efforts of San Francisco Opera Guild in reaching out to the young people of the Bay Area. It means so much to me because I know firsthand of these efforts and have seen the amazing results. I applaud the Guild’s Director of Education Caroline Altman and her work with the Opera Scouts and the amazing team at the Guild. Music changed my life, and I’m excited to celebrate how it changes the lives of our precious young people.” Jake Heggie said: “I'm delighted to join with my great friend Frederica von Stade to spotlight the important, ongoing work in music education made possible by San Francisco Opera Guild.