6 Interpretations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copper in the Early Modern Sino-Japanese Trade Monies, Markets, and Finance in East Asia, 1600–1900

Copper in the Early Modern Sino-Japanese Trade Monies, Markets, and Finance in East Asia, 1600–1900 Edited by Hans Ulrich Vogel VOLUME 7 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mmf Copper in the Early Modern Sino-Japanese Trade Edited by Keiko Nagase-Reimer LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: From “Scroll with views of the Dutch Factory and Chinese Quarter in Nagasaki 唐館図 蘭館図絵巻” drawn by Ishizaki Yūshi 石崎融思. Courtesy of Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture 長崎歴史文化博物館. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Nagase-Reimer, Keiko. Title: Copper in the early modern Sino-Japanese trade / edited by Keiko Nagase-Reimer. Description: Leiden : Brill, 2016. | Series: Monies, markets, and finance in East Asia, 1600-1900, ISSN 2210-2876 ; volume 7 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015029107| ISBN 9789004299450 (hardback : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9789004304512 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Copper industry and trade—Japan—History. | Copper industry and trade—China—History. | Japan—Commerce—China—History. | China--Commerce—Japan—History. | Japan—Economic conditions—1600–1868. Classification: LCC HD9539.C7 J323 2016 | DDC 382/.4566930952—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015029107 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 2210-2876 isbn 978-90-04-29945-0 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30451-2 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. -

SAN JOSE Food Works FOOD SYSTEM CONDITIONS & STRATEGIES for a MORE VIBRANT RESILIENT CITY

SAN JOSE Food Works FOOD SYSTEM CONDITIONS & STRATEGIES FOR A MORE VIBRANT RESILIENT CITY NOV 2016 Food Works SAN JOSE Food Works ■ contents Executive Summary 2 Farmers’ markets 94 Background and Introduction 23 Food E-Commerce Sector 96 San Jose Food System Today 25 Food and Agriculture IT 98 Economic Overview 26 Food and Agriculture R & D 101 Geographic Overview 41 Best Practices 102 San Jose Food Sector Actors and Activities 47 Summary of Findings, Opportunities, 116 County and Regional Context 52 and Recommendations Food Supply Chain Sectors 59 APPENDICES Production 60 A: Preliminary Assessment of a San Jose 127 Market District/ Wholesale Food Market Distribution 69 B: Citywide Goals and Strategies 147 Processing 74 C: Key Reports 153 Retail 81 D: Food Works Informants 156 Restaurants and Food Service 86 End Notes 157 Other Food Sectors 94 PRODUCED BY FUNDED BY Sustainable Agriculture Education (SAGE) John S. and James L. Knight Foundation www.sagecenter.org 11th Hour Project in collaboration with San Jose Department of Housing BAE Urban Economics Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority www.bae1.com 1 San Jose Executive Summary What would San Jose look like if a robust local food system was one of the vital frameworks linking the city’s goals for economic development, community health, environmental stewardship, culture, and identity as the City’s population grows to 1.5 million people over the next 25 years? he Food Works report answers this question. The team engaged agencies, businesses, non- T profits and community groups over the past year in order to develop this roadmap for making San Jose a vibrant food city and a healthier, more resilient place. -

A Naturalist Lost – CP Thunberg's Disciple Johan Arnold

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository A naturalist lost – C. P. Thunberg’s disciple Johan Arnold Stützer (1763–1821) in the East Indies Wolfgang, Michel Faculty of Languages and Cultures, Kyushu University : Professor emeritus http://hdl.handle.net/2324/1563681 出版情報:Japanese collections in European museums : reports from the Toyota-Foundation- Symposium Königswinter 2003. 3, pp.147-162, 2015-03-01. Bier'sche Verlagsanstalt バージョン: 権利関係: A NATURALIST LOST - C. P. THUNBERG'S DISCIPLE JOHAN ARNOLD STUTZER (1763-1821) IN THE EAST INDIES Wolfgang MICHEL, Fukuoka Johan Arnold Stiitzer was one of two disciples man barber surgeon, Martin Christian Wilhelm of the renowned Swedish scholar Carl Peter Stiitzer (1727- 1806). Martin Stiitzer had im Thunberg who traveled overseas as an employ migrated from Oranienburg (Prussia) to Stock ee of the Dutch East India Company to lay the holm during the 17 50s. After traveling to the foundations of an academic career. Following West Indies in 1757 and undertaking further in the footsteps of his famous teacher, he even studies including an examination to become managed to work as a surgeon at the Dutch trad a surgeon in 1760, he married Anna Maria ing post ofDejima in Nagasaki. However, after Soem (?- 1766), whose father, Christian Soem years of rapidly changing circumstances and ( 1694-1775), was also a barber surgeon. 1 twists and turns, this promising young naturalist Surgeons were educated and organized settled down to serve the British in Ceylon with in guilds and, like his father-in-law, Martin out ever returning to Europe. While most of the Stiitzer took part in the fight for recognition objects collected by Westerners in Japan ended and reputation. -

Objects Collapse Time. Through Archaeology, the Unreachable Past Becomes Tangible Again. in This Way, Archaeology Mitigates

Chinese Historical and Cultural Project was founded in 1987, shortly after discovery of the Market Street Chinatown artifacts in 1985. Through a long process, the 400 boxes of artifacts recovered from the Market Street Chinatown were eventually brought to History San José, and then loaned to Stanford University for their archaeology program. We were so pleased because otherwise all those artifacts would still be sitting there, without being seen or touched. City Beneath the City brings to the forefront that there were Chinese here in early San Jose. There were actually five Chinatowns in San Jose, and today there are none. This exhibition is, in a way, an extension of Chinese Historical and Cultural Project’s work to promote education by displaying the culture and the history of the early Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans in Santa Clara Valley. Both at the Chinese American History Museum at History Park and in a travelling exhibit that is displayed in libraries and other public buildings throughout Santa Clara County, we are trying to share our culture and our history and the contributions we have made. Anita Kwock, Technology Resource Teacher, San Jose Unified School District President, Chinese Historical and Cultural Project The French Jesuit scholar Michel de Certeau once described urban spaces as “haunted.” More than present-day centers of commerce and industry, our cities must be experienced imaginatively through the stories and legends that metaphorically inhabit them. The streets of a city “offer to store up rich silences and wordless stories,” according to de Certeau. City Beneath the City is not an exhibition of objects from a lost city, but an exhibition of the stories these objects tell – past, present, and future. -

Japanese Monetary Policy and the Yen: Is There a “Currency War”? Robert Dekle and Koichi Hamada

Japanese Monetary Policy and the Yen: Is there a “Currency War”? Robert Dekle and Koichi Hamada Department of Economics USC Department of Economics Yale University April 2014 Very Preliminary Please do not cite or quote without the authors’ permission. All opinions expressed in this paper are strictly those of the authors and should not necessarily be attributed to any organizations the authors are affiliated with. We thank seminar participants at the University of San Francisco, the Development Bank of Japan, and the Policy Research Institute of the Japanese Ministry of Finance for helpful comments. Abstract The Japanese currency has recently weakened past 100 yen to the dollar, leading to some criticism that Japan is engaging in a “currency war.” The reason for the recent depreciation of the yen is the expecta- tion of higher inflation in Japan, owing to the rapid projected growth in Japanese base money, the sum of currency and commercial banking reserves at the Bank of Japan. Hamada (1985) and Hamada and Okada (2009) among others argue that in general, the expansion of the money supply or the credible an- nouncement of a higher inflation target does not necessarily constitute a “currency war”. We show through our empirical analysis that expan- sionary Japanese monetary policies have generally helped raise U.S. GDP, despite the appreciation of the dollar. 1 Introduction. The Japanese currency has recently weakened past 100 yen to the dollar, leading to criticism that Japan is engaging in a “currency war.” The reason for the recent depreciation of the yen is the expectation of higher inflation in Japan, owing to the rapid projected growth in Japanese base money, the sum of currency and commercial banking reserves at the Bank of Japan. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Migration, Social Network, and Identity: The Evolution of Chinese Community in East San Gabriel Valley, 1980-2010 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8c60v1bm Author Hung, Yu-Ju Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Migration, Social Network, and Identity: The Evolution of Chinese Community in East San Gabriel Valley, 1980-2010 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Yu-Ju Hung August 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Clifford Trafzer, Chairperson Dr. Larry Burgess Dr. Rebecca Monte Kugel Copyright by Yu-Ju Hung 2013 The Dissertation of Yu-Ju Hung is approved: ____________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would hardly have possible without the help of many friends and people. I would like to express deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Clifford Trafzer, who gave me boundless patience and time for my doctoral studies. His guidance and instruction not only inspired me in the dissertation research but also influenced my interests in academic pursuits. I want to thank other committee members: Professor Larry Burgess and Professor Rebecca Monte Kugel. Both of them provided thoughtful comments and valuable ideas for my dissertation. I am also indebted to Tony Yang, for his painstaking editing and proofreading work during my final writing stage. My special thanks go to Professor Chin-Yu Chen, for her constant concern and insightful suggestions for my research. -

Title Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Type Thesis URL

Title Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Type Thesis URL http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/6205/ Date 2013 Citation Spławski, Piotr (2013) Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939). PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Creators Spławski, Piotr Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Piotr Spławski Submitted as a partial requirement for the degree of doctor of philosophy awarded by the University of the Arts London Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) Chelsea College of Art and Design University of the Arts London July 2013 Volume 1 – Thesis 1 Abstract This thesis chronicles the development of Polish Japonisme between 1885 and 1939. It focuses mainly on painting and graphic arts, and selected aspects of photography, design and architecture. Appropriation from Japanese sources triggered the articulation of new visual and conceptual languages which helped forge new art and art educational paradigms that would define the modern age. Starting with Polish fin-de-siècle Japonisme, it examines the role of Western European artistic centres, mainly Paris, in the initial dissemination of Japonisme in Poland, and considers the exceptional case of Julian Żałat, who had first-hand experience of Japan. The second phase of Polish Japonisme (1901-1918) was nourished on local, mostly Cracovian, infrastructure put in place by the ‘godfather’ of Polish Japonisme Żeliks Manggha Jasieski. His pro-Japonisme agency is discussed at length. -

Federal Reserve Banks

Skip to Content Release dates Current release Other formats: ASCII | PDF (51 KB) MINORITY OWNED DEPOSITORY INSTITUTIONS and THEIR BRANCHES as of June 30, 2015 State of CALIFORNIA - ( Assets and Deposits in Thousands ) Holding Minority Company Established Institution/Branch Name Location ID Chtr Class Ent Type Min Cd Ownership Assets Deposits Dt Name Dt AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BK , ARCADIA BR ARCADIA, CA 4580694 3/31/2015 9/23/2013 AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BK , CHINO HILLS BR CHINO HILLS, CA 4201690 3/31/2015 3/6/2008 AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BK , SAN GABRIEL BR SAN GABRIEL, CA 3553570 3/31/2015 10/23/2006 AMERICAN PLUS BK NA ARCADIA, CA 3623110 117 NAT 20 11/1/2008 8/8/2007 $327,835 $253,082 AMERICAN PLUS BK NA , PASADENA BR PASADENA, CA 4852403 8/27/2014 8/27/2014 ROWLAND AMERICAN PLUS BK NA , ROWLAND HGTS BR 4094173 8/15/2009 8/15/2009 HEIGHTS, CA AMERICAS UNITED BK GLENDALE, CA 3488980 207 NMB 10 1/11/2007 11/6/2006 $169,328 $138,980 AMERICAS UNITED BK , DOWNEY BR DOWNEY, CA 4435963 12/30/2010 12/30/2010 AMERICAS UNITED BK , GLENDALE BR GLENDALE, CA 4811295 12/31/2012 12/31/2012 AMERICAS UNITED BK , LANCASTER BR LANCASTER, CA 87962 3/28/2014 3/31/1967 ASIAN PACIFIC NB SAN GABRIEL, CA 1462986 117 NAT 20 2/3/2004 7/25/1990 $55,888 $46,725 ROWLAND ASIAN PACIFIC NB , ROWLAND HGTS RGNL OFF 2641854 2/3/2004 12/3/1997 HEIGHTS, CA SAN FRANCISCO, BANK OF THE ORIENT 777366 217 SMB ORIENT BC 20 9/22/1992 3/17/1971 $457,627 $384,792 CA BANK OF THE ORIENT , MILLBRAE BR MILLBRAE, CA 2961682 11/15/1999 11/15/1999 BANK OF THE ORIENT , OAKLAND BR OAKLAND, CA -

Money in Modern Japan

Money in Modern Japan Japan is one of the oldest states in the world: in over 2000 years the island nation has slowly and continuously developed culturally, socially, politically and economically into the country that it is today. It is characteristic that Japan never fell under the domination of a foreign power during this time – not until after World War II, however, when it was occupied by the Americans for some years (1945- 1952). That does not mean, of course, that no external influences were adopted. On the contrary: until the end of the Japanese Middle Ages (about 1200-1600), Japan was completely geared towards its great neighbor China. From there it adopted cultural, political and economic achievements, among them also money. Well into the 16th century, the Japanese cast coins following Chinese models. In addition, masses of cash coins (ch'ien) imported from China were in circulation. With the beginning of modern times around 1600, a radical turn around took place. Under the government of the Tokugawa shoguns (the Edo period, 1603-1867) the island nation cut itself off almost completely from the outside world. In this time an independent Japanese culture evolved – and a coinage system of its own, whose principal feature was the simultaneous circulation of a gold and a silver currency. 1 von 12 www.sunflower.ch Japanese Empire, Edo Period, Shogun Tokugawa Ietsugu (1712-1716), Kobankin 1714, Edo Denomination: Kobankin Mint Authority: Shogun Tokugawa Ietsugu Mint: Edo (Tokyo) Year of Issue: 1714 Weight (g): 17.8 Diameter (mm): 69.5 Material: Gold Owner: Deutsche Bundesbank Japan was united towards the end of the 16th century after long years of civil war. -

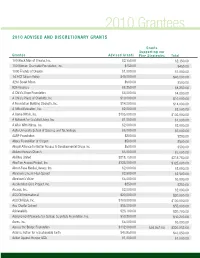

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised and Discretionary Grants

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised And discretionAry GrAnts Grants supporting our Grantee Advised Grants Five strategies total 100 Black Men of Omaha, Inc. $2,350.00 $2,350.00 100 Women Charitable Foundation, Inc. $450.00 $450.00 1000 Friends of Oregon $1,000.00 $1,000.00 1st ACT Silicon Valley $40,000.00 $40,000.00 42nd Street Moon $500.00 $500.00 826 Valencia $8,250.00 $8,250.00 A Child’s Hope Foundation $4,000.00 $4,000.00 A Child’s Place of Charlotte, Inc. $10,000.00 $10,000.00 A Foundation Building Strength, Inc. $14,000.00 $14,000.00 A Gifted Education, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 A Home Within, Inc. $105,000.00 $105,000.00 A Network for Grateful Living, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Wish With Wings, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Aalto University School of Science and Technology $6,000.00 $6,000.00 AARP Foundation $200.00 $200.00 Abbey Foundation of Oregon $500.00 $500.00 Abigail Alliance for Better Access to Developmental Drugs Inc $500.00 $500.00 Abilene Korean Church $3,000.00 $3,000.00 Abilities United $218,750.00 $218,750.00 Abortion Access Project, Inc. $325,000.00 $325,000.00 About-Face Media Literacy, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Abraham Lincoln High School $2,500.00 $2,500.00 Abraham’s Vision $5,000.00 $5,000.00 Accelerated Cure Project, Inc. $250.00 $250.00 Access, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 ACCION International $20,000.00 $20,000.00 ACCION USA, Inc. -

October 2016

Saratoga Historical Foundation PO Box 172, Saratoga CA 95071 October 2016 Support the October 15 Saratoga Historical Foundation Estate Sale Today!!!! Celebrate India Showcase! October 23 Time to Shop—It’s An Estate Sale! Celebrate India Showcase The Saratoga Historical Foundation will be holding an For the second year, the Saratoga Historical estate sale on Saturday October 15 from 9 to 3 PM. Foundation is hosting the India Showcase at the Grab your wallet and come on by and find a treasure Saratoga History Museum October 23 from 1-4 PM or two. and is free to the public. According to Fund Development Director Bob Himel The event will include Asian Indian arts and crafts, the estate sale has a big selection of vintage jewelry, food, dance demonstration, music, and more. collectible artwork, antiques, garden items, plants, According to Event Coordinator Rina Shah, “the kitchenware, and more. our Donations!!event will include classical folk, Bollywood and other Funds from the estate sale will be used to construct a dances by five groups: Shilpa Padwekar, Saratoga blacksmith exhibit located at the Saratoga Historical High School Bollywood dance group, Sanjana, Park. The educational exhibit will showcase the Saratoga adult dance group, and Priya Krishnamurth’s museum's collection of farm and timber tools. The dance group.” interactive exhibit will also include sound effects. Other activities include Kailash Ranganathan with The fundraiser will run from 9 AM to 3 PM on the instrumental music on the sitar. Bela Desai will sing museum's patio at 20450 Saratoga-Los Gatos Road inhere! traditional songs.