Special Issue on Thinking Gender 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside-Outside on the Work of Petra Blaisse and the Architecture of the Drape

Dirk van den Heuvel I wish to thank Petra Blaisse, without whom this article would not have been Inside-outside possible. I had a number of extensive conversations with her about her work. She was also very helpful with the On the work of Petra Blaisse selection and provision of illustrations. 1 and the architecture The most interesting publications in this connection are: Hans Kollhoff (ed.), Uber Tektonik in der Baukunst, of the drape Braunschweig/Wiesbaden, 1993; Werner Oechslin, Stilhulse und Kern. Otto Wagner, Adolf Laos und der evolu tionare Weg zur modernen Architectur, 1994; Origins Zurich/Berlin, Kenneth Frampton, Studies into tectonic culture. The poetics of construction in nineteenth and For a long time, the drape was unthinkable as a part of architec twentieth century architecture, ture. Modern architectural thinking was dominated by structure Cambridge/London, 1995; Mark Wigley, and construction. Rereadings of Gottfried Semper's theories White walls, designer dresses. The brought about a radical change in the description of contemporary fashioning of modern architecture, Cambridge/London, 1995; Harry Francis architectural production. In retrospect, this rereading has led to Mallgrave, Gottfried Semper, architect of fundamental rewritings of the history of modern architecture. the nineteenth century, New The textile, the woven material that Semper indicated as one of Haven/London, 1996. the original, or primal, sources of architecture, was further 2 elaborated into a possible tectonic theory of architecture. Te xtile, Henk Engel, 'Stijl en expressie', in: Jan de Heer (ed.), Kleuren architectuur, moreover, was linked with an understanding of the outer wall as Rotterdam, 1986, pp. 63-74. -

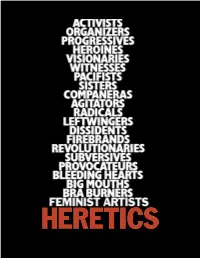

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930S-2007, Bulk 1960-1990

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930s-2007, bulk 1960s-1990, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie L. Ashley and Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 May Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1960s-circa 1980s........................................ 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1950s-2006.................................................................. 7 Series 3: Writings, 1930s-1990s........................................................................... -

OMA at Moma : Rem Koolhaas and the Place of Public Architecture

O.M.A. at MoMA : Rem Koolhaas and the place of public architecture : November 3, 1994-January 31, 1995, the Museum of Modern Art, New York Author Koolhaas, Rem Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/440 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THRESHOLDS IN CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE O.M.A.at MoMA REMKOOLHAAS ANDTHE PLACEOF PUBLICARCHITECTURE NOVEMBER3, 1994- JANUARY31, 1995 THEMUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK THIS EXHIBITION IS MADE POSSIBLE BY GRANTS FROM THE NETHERLANDS MINISTRY OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, LILY AUCHINCLOSS, MRS. ARNOLD L. VAN AMERINGEN, THE GRAHAM FOUNDATION FOR ADVANCED STUDIES IN THE FINE ARTS, EURALILLE, THE CONTEMPORARY ARTS COUNCIL OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, AND KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES. REM KOOLHAASAND THE PLACEOF PUBLIC ARCHITECTURE ¥ -iofiA I. The Office for Metropolitan Architecture (O.M.A.), presence is a source of exhilaration; the density it founded by Rem Koolhaas with Elia and Zoe engenders, a potential to be exploited. In his Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesendorp, has for two "retroactive manifesto" for Manhattan, Delirious decades pursued a vision energized by the relation New York, Koolhaas writes: "Through the simulta ship between architecture and the contemporary neous explosion of human density and an invasion city. In addition to the ambitious program implicit in of new technologies, Manhattan became, from the studio's formation, there was and is a distinct 1850, a mythical laboratory for the invention and mission in O.M.A./Koolhaas's advocacy of the city testing of a revolutionary lifestyle: the Culture of as a legitimate and positive expression of contem Congestion." porary culture. -

Front Cover: Foster + Partners, Kamakura House, Kamakura, Japan, 2004

44 Interior Atmospheres Architectural Design May/June 2008 Interior Atmospheres 4 Guest-edited by Julieanna Preston ISBN-978 0470 51254 8 Profile No 193 Vol 78 No 3 CONTENTS 4 Editorial Offices Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to: International House Permissions Department, 4 30 Ealing Broadway Centre John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Editorial Olafur Eliasson and the London W5 5DB The Atrium Southern Gate Helen Castle Circulation of Affects and T: +44 (0)20 8326 3800 Chichester, Percepts: In Conversation F: +44 (0)20 8326 3801 West Sussex PO19 8SQ E: [email protected] England 6 Hélène Frichot Introduction Editor F: +44 (0)1243 770620 Helen Castle E: [email protected] In the Mi(d)st Of 36 Julieanna Preston Affecting Data Production Editor Subscription Offices UK Elizabeth Gongde John Wiley & Sons Ltd Julieanna Preston Project Management Journals Administration Department 12 Caroline Ellerby 1 Oldlands Way, Bognor Regis West Sussex, PO22 9SA This is Not Entertainment: 46 Design and Prepress T: +44 (0)1243 843272 Experiencing the Dream House Multivalent Performance in the Artmedia Press, London F: +44 (0)1243 843232 E: [email protected] Ted Krueger Work of Lewis.Tsurumaki.Lewis Printed in Italy by Conti Tipocolor Paul Lewis, Marc Tsurumaki [ISSN: 0003-8504] Advertisement Sales 16 and David J Lewis Faith Pidduck/Wayne Frost 4 is published bimonthly and is available to Making Sense: The MIX House T: +44 (0)1243 770254 purchase on both a subscription basis and as E: [email protected] individual volumes at the following prices. Joel Sanders and Karen Van 54 Lengen Condensation: Editorial Board Single Issues Will Alsop, Denise Bratton, Mark Burry, André Single issues UK: £22.99 Regionalism and the Room in Chaszar, Nigel Coates, Peter Cook, Teddy Cruz, Single issues outside UK: US$45.00 20 John Yeon’s Watzek House Max Fordham, Massimiliano Fuksas, Edwin Details of postage and packing charges Heathcote, Michael Hensel, Anthony Hunt, available on request. -

Warping the Architectural Canon

EXCERPT from “Thinking GENDER IN SPACE, PLACE, AND Dance,”TG 2012 PLENARY SESSION BY JAMIE ARON WARPING THE ARCHITECTURAL CANON EXTILES have long been a part of the manual skill rather than individual creativity intersected architecture at key moments in the canon of Western architecture—from the or intellectual drive. Eventually, through hard twentieth century, but also challenged the hier- Tfolds of draped female forms in ancient lobbying by Renaissance artists and humanists, archical position and cultural agency of architec- Greek temples to the abstract Mayan patterns the establishment of art academies dedicated ture. “knitted” together in Frank Lloyd Wright’s textile exclusively to the teaching of architecture, paint- In the early twentieth century, modern archi- block houses of the 1920s. Yet just as any façade ing and sculpture, and theoretical backing by tects and theorists reacted to broad social changes may conceal what’s inside, architecture’s shared Enlightenment philosophers, architecture sepa- brought about by Industrialization and social history with weaving is often obscured. Today rated from its mechanical compatriots to become and political upheaval by rejecting the historic architecture sits at the top alongside the “fine arts” one of the dominant “visual arts” of modernity, forms of the past. Partly due to theoretical build of painting and sculpture, while woven textiles leaving weaving behind as handicraft within the up from 19th century aesthetic debates on style occupy a less prominent position in the “applied” category of the “decorative arts.” It’s no secret that and the value of ornament, modern architects or the “decorative arts.” Appearing natural now, women have been generally left out of modern theorized that even textiles, considered inher- few remember that the hierarchy of the arts was visual art history and associated with the deco- ently ornamental within the interior, needed to be not always so stable. -

Jmoreno (1).Pdf

Abstract Applications in Interior+Landscape is a study on how infl uences from the studies of Landscape Architecture and Architectural Interiors may provide solutions to certain sites in our modern built environment. In addi- tion, the study also focuses on intentionally fi nding a connection between certain Interior spaces and their immediate landscapes for better access to Landscape atmospheres without being out in the elements, for more convenience in dense urban sites where a personal exterior space is often missing or inconvenient to visit, and for having the luxury of bringing the landscape in or the Interiors out for more inviting sites,less concealed spaces where desired and for any natural benefi ts associated with these. The study concentrates on many different applications that an individual or a multidisciplinary fi rm that em- ploys Landscape and Interiors professionals may use in designing and renovating certain sites. The main focus is on the common ground of space planning between small scale Landscape and Interiors which builds, decorates, transforms and reprograms where Building architecture and dated Landscape design has previously worked upon. Examples and concepts are presented and then developed for new applications. The study ends with a small scale Landscape urban infi ll design and an Interior Design of the space right next to it; designed simultaneously in regard to each other. 1 I N T E R I O R + L A N D S C A P E Dedication: To my parents for making me believe I could achieve something bigger than what I initially set out to do, and to the hard working people of El Salvador for maintaining the beautyful land and always struggling for progress. -

Reviews for the Special Collection on Architectural Historiography and Fourth Wave Feminism 2020

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Merrett, AJ, et al. 2020. Reviews for the Special Collection on Architectural Historiography and Fourth Wave Feminism 2020. Architectural Histories, 8(1): +LVWRULHV 25, pp. 1–7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.560 REVIEW Reviews for the Special Collection on Architectural Historiography and Fourth Wave Feminism 2020 Andrea J. Merrett, Inés Toscano and Olivier Vallerand Merrett, AJ. A Review of Doris Cole, From Tipi to Skyscraper: A History of Women in Architecture. Boston: i Press, 1973. Toscano, I. A Review of G. Cascelli Farinasso, et al., Arquitetas (in)visíveis, 2014, https://www.arquiteta- sinvisiveis.com/; M. McLeod and V. Rosner, Pioneer Women of American Architecture, 2014, https:// pioneeringwomen.bwaf.org/; I. Moisset, et al., Un día|Una arquitecta, 2015, https://undiaunaarquitecta. wordpress.com/. Vallerand, O. A Review of Elizabeth Otto, Haunted Bauhaus: Occult Spirituality, Gender Fluidity, Queer Identities, and Radical Politics. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2019. Against the ‘Stars’ Andrea J. Merrett Independent Scholar [email protected] Doris Cole, From Tipi to Skyscraper: A History of Women in Architecture, Boston: i Press, 136 pages, 1973, ISBN: 0913222011 Doris Cole’s From Tipi to Skyscraper (1973) was the first history of women in architecture published in the United States (Figure 1). Although a slim volume, it made a sig- nificant historiographical contribution to feminist litera- ture in architecture when it was published. This contri- bution was due in part to the limited scholarly resources available but also to Cole’s position outside academia, which allowed her to draw on sources that might have been frowned upon otherwise. -

Tussen Binnen En Buiten Between Inside and Outside

73 Dirk van den Heuvel z �- z Vl Vl Tussen binnen en buiten ::J f- Meervoudigheid en simultane'fteit in het werk van Petra Blaisse Between Inside and Outside Multiplicity and Simultaneity in the Work of Petra Blaisse I Video images. A cloth, gold in colour, sways sound Videobeelden. Een doek, goudkleurig, wiegt geluidloos lessly from inside to outside and back again. Lightly van binnen naar buiten, en terug. Licht en tegelijkertijd yet languidly it drags across the granito floor of the loom sleept het over de granito-vloer van de woonkamer, living room, then across the grass. dan weer over het gras. The house and its garden are the Villa dall'Ava in Het huis en de tuin zijn de Villa dall' Ava te Parijs Paris, designed by OMA. The curtain is the work of ontworpen door OMA. Het gordijn is het werk van Petra Petra Blaisse. There are a few scattered remarks Blaisse. In het boek S,M,L,XL staan een paar losse about the curtain in the book S,M,L,XL, scribbled in opmerkingen over het gordijn, opgekrabbeld bij de the sketches: ontwerptekeningen: 'Tra jectory of yellow silk curtain to make room in 'Trajectory of yellow silk curtain to make room in the the room.' room.' 'Tra jectory' - signals movement and transience. 'Trajectory'- beweging en tijdelijkheid liggen erin 'Yellow silk'- an emphasis on lightness, an intense opgesloten. interest in the surface. 'Yellow silk'- benadrukking van lichtheid, een hevige interesse voor het oppervlak. There are other comments in the book, about the neighbours and a court case. -

The Master of Bigness, Martin Filler

The Master of Bigness By Martin Filler May 10, 2012 OMA/Progress an exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, October 6, 2011–February 19, 2012 Project Japan: Metabolism Talks… by Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist, edited by Kayoko Ota and James Westcott Taschen, 717 pp., $59.99 (paper) A rendering of the China Central Television Headquarters in Beijing, designed by Rem Koolhaas’s architecture firm, OMA, in partnership with the engineering firm Arup. Begun in 2004, the building is now largely completed but has yet to be occupied. With his prodigious gift for invention, shrewd understanding of communication techniques, and contagiously optimistic conviction that modern architecture and urban design still possess enormous untapped potential for the transformation of modern life, no master builder since Le Corbusier has offered a more impressive vision for a brighter future than the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. To be sure, there are other present-day architects also at the very apex of the profession who do certain things better than he does. Robert Venturi is a finer draftsman and a more elegant writer; Denise Scott Brown has a more empathetic feel for the social interactions that inform good planning; and Frank Gehry displays a sharper eye for sculptural assemblage and a keener instinct for popular taste. But when it comes to sheer conceptual audacity and original thinking about the latent possibilities of the building art, Koolhaas today stands unrivaled. Through his Rotterdam-based practice, the Office for Metropolitan Archi- -

Inside Outside

BOOKS BOOKS INSIDE OUTSIDE Petra Blaisse known for her long collaboration with these words into a picture essay specifically with OMA she has worked of textures, thoughts, flowers and with UN Studio, SANAA/Kazuyo colours, and the first page throws back Sejima, Macken & Macken, Michael like one of Blaiss’s curtains. It is an Maltzan, Tim Ronalds and Jean Novel appropriate way to begin our discovery to name a few. of the projects, the dilemmas, ideas, personalities and locations that make This new extensive book is long up Blaisse’s world. overdue, and shows the full range of Petra Blaisse’s work for the first time. When you see her work, you realize The words are all mainly by Blaisse the implicit difficulty in representing it herself with short essays and in book form. The hand needs to thoughts by Chris Dercon, Tim touch; light fall through the material Ronalds, Cecil Balmond, Sanford and trees move in the wind. But the Kwinter and others. Irma Boom’s subtle balance between word, image hand as the designer of the book is and sequence is carefully interlaced in In the opening sequences of the film unmistakable. She creates a rich the design of the book, to hint at the dialogue and empathy with Blaisse’s crafted materiality and evolution of L Ratcatcher by Lynne Ramsay we stunning though it is- but a mixture revisiting years after completion -not In the architecture and design world, work and approach in both how the her designs. watch the central character (James) of diary, photo album and scrapbook in the project as such but in the reality we tend to get obsessed with book has been graphically conceived wrap himself in a curtain and spin that tells her own story of how she of the prison situation. -

First Paragraph

Short Biography Petra Blaisse Dutch designer Petra Blaisse works in a multitude of creative areas, including textile, landscape and exhibition design. She founded Inside Outside in Amsterdam in 1991. Inside Outside specializes in the rare combination of both interior and exterior design, interweaving architecture and landscape. These interior projects are not only visual interventions that are made of materials that change their architectural context and introduce color, flexibility and movement, but they also function to solve acoustic, climatic, shading and spatial necessities. The landscape projects reflect the same fascination with – and a continuous research of - materials, light and movement combined with urban and infrastructural program. This mentality brings forth a series of strong, multi-layered garden and park designs that combine logistics with rich planting schemes and graphic effects. Blaisse first gained international acclaim for her exhibition installations, theatre curtains, acoustic walls and poured floors. The traveling exhibits on OMA’s work in the eighties and nineties; the embossed ‘liquid gold’ drapes for the Netherlands Dance Theatre in The Hague; the ‘sound curtain’ for the Kunsthal in Rotterdam; back lit curtains and poured floors for Lille Grand Palais; the multi-layered curtain walls for the Mick Jagger Centre concert hall in London; the ‘Garden Carpets’ and reversible curtains for the Seattle Central Library; the pleated and knitted curtains for the PRADA stores in New York and Los Angeles; and the large flowered ‘jacquard’ curtains for the Dutch Embassy in Berlin are a few of Blaisse’s most recognised works. The combined landscape and interior design for the McGormick Tribune Campus Building in Chicago and Seattle Central Library (2000-2004) (both by architects OMA) recently brought Blaisse’s work to the attention of a broader public.