Union College 2006-2007 Academic Register

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quick Facts / Table of Contents Quick Facts

QUUICKICK FAACTSCTS / TAABLEBLE OOFF COONTENTSNTENTS UNION COLLEGE QUICK FACTS Athletics at Union Inside Front Cover Location: Barbourville, Ky. 40906 Quick Facts/Table of Contents 1 Founded: 1879 Enrollment: 1,350 This is Union! 2 Nickname: Bulldogs Colors: Orange/Black Robsion Arena 3 Fieldhouse (capacity): Robsion Arena (1,800) 2007-08 Bulldog Preview 4-5 Affi liations: Appalachian Athletic Conference and NAIA Coaching Staff 6 President: Edward D. de Rosset (Berea ’67) Head Coach Kelly Combs 6 Athletic Director: Darin S. Wilson (Union ’96) Assistant Coach Jerry Nichols 6 Phone: (606) 546-1308 The Bulldogs 7-10 Directory of Compliance/FAR: Larry Inkster 2007-08 Roster 7 Associate AD: Tim Curry Player Profi les 8-13 2006-07 Season in Review 14-19 Assistant AD: Tommy Reid 2006-07 Season In Review 14 Athletic Secretary: Lana Faulkner 2006-07 Team & Individual Stats 15-16 Appalachian Athletic Conference Standings and Stats 17-18 Men’s Basketball History 2006-07 AAC All-Conference Team 19 First year of program: 1920 Affi liations 20-21 Post-Season Record: 0-1 (1 appearance) The Appalachian Athletic Conference 20 Last Post-Season Appearance: 1968 The NAIA 21 Last Post-Season Result: Lost 75-69 to Drury (Mo.), 1968 2007-08 Opponents 22-24 All-Time Record: 991-954-1 (.510) in 82 seasons Bulldog Record Book 25-26 Conference Championships: 7 (KIAC in 1949-50, 1964-65, 1965-66, Individual & Team Records 25 1967-68, 1968-69, 1970-71, 1971-72) Bulldog Honors 25 Conference Tournament Championships: 6 (KIAC in 1946, Year-by-Year & Coaching Records 26 1968, 1969, 1971, 1972; SMAC in 1950) College and Staff 27-28 NAIA District 24 Championships: 1 (1968) Athletic Administration 27 NAIA National Championship Tournament App.: 1 (1968) Athletic Staff Directory 28 20-Win Seasons: 10 Media Information Inside Back Cover Last 20-Win Season: 10 2007-08 Schedule/2007-08 Team Photo Back Cover Team Sports Information CREDITS SID: Jay Stancil The 2007-08 Union College Men’s Basketball Media Guide is a publication of Email: [email protected] the UC Offi ce of Sports Information. -

2017-2018 RSPH Catalog

ROLLINS SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH CATALOG 2 0 1 7 - 2 0 1 8 Rollins School of Public Health CONTENTS | 3 Emory University 1518 Clifton Road, N.E. Atlanta, Georgia 30322 Letter From The Dean ........................................................................................ 5 Rollins School of Public Health Admissions and Student Services: 404.727.3956 The University.................................................................................................... 6 Monday–Friday, 8:30 a.m.–5:00 p.m. Rollins School of Public Health......................................................................... 7 Educational Resources ..................................................................................... 28 See page 244 for additional directory information. Academic Policies............................................................................................ 36 Honor and Conduct Code................................................................................. 42 Visit us on the web at www.sph.emory.edu. Degree Programs ............................................................................................. 53 Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education ............................. 55 Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics .............................................. 71 Department of Environmental Health .............................................................. 92 EQUAL OPPORTUNITY POLICY Emory University is dedicated to providing equal opportunities to all individuals regardless of -

2017-2018 Undergraduate Catalog

TE CATALOG TE A U MAKE YOUR MARK MAKE YOUR UNDERGRAD 2017 / 2018 2017/2018 UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG 701 College Road Lebanon, IL 62254 618-537-4481 www.mckendree.edu i Admissions 2017 / 2018 UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG ON THE COVER: 701 College Road MCKENDREE UNIVERSITY Lebanon, IL 62254 GONFALON 618-537-4481 1-800-BEARCAT Gonfalons originated in medieval Italy as a signal of state www.mckendree.edu or office, but has been adopted by universities around the world as insignias of schools or colleges. Our gonfalons, or academic banners, designate the University, the College of Arts and Sciences, the School of Business, the School of Education, and the School of Nursing and Health Professions. ii McKendree University 2017/2018 UndergraduateT Cataloghe University Mission ..................... 5 Admission .........................................13 Student Services ..............................23 Academic Policies ............................25 General Education Program ..........51 ACCREDITATIONS MEMBERSHIPS Courses of Study Higher Learning Commission American Association College of Arts and Sciences ....59 230 South LaSalle St. of Colleges for Teacher Suite 7-500 Education (AACTE) Art • Art History • Art Education • Chicago, IL 60604-1413 Biochemistry • Biology • Chemistry American Association 800-621-7440 • Computing (Computer Science, of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) Computer Information Systems, Commission on Accreditation American Council on of Athletic Training Education Computational Science, and Education (ACE) (CAATE) Information Technology) -

Experience 1 Thethe All-Importantall-Important Detailsdetails

experience 1 thethe all-importantall-important detailsdetails bulletin 2016–2017 Bulletin 2016–2017 contact us volume 78 www.ucollege.edu [email protected] p 800.228.4600 p 402.486.2529 f 402.486.2584 Published by Union College © 2016. Union College reserves the right to change any provisions or requirements contained in this publication. 3800 S. 48th St., Lincoln, NE 68506 • [email protected] • ucollege.edu President’s Message Are you ready to change the world? Others before you have done it. Whether building breakthrough technology that is changing the lives of diabetics, creating a learning television show that influenced an entire generation or providing health care in remote African villages, Union graduates are changing the world. Sounds daunting, right? It doesn’t have to be. God created you for a purpose and gave you the unique talents and abilities to accomplish that purpose. With Him, you can change your world. At Union College, you will discover a community ready to do everything possible to prepare you to be the best at what you do. We will help you learn to think critically, address complex problems, explore new cultures, and use modern technologies and information resources—all vital skills most valued by employers. But more importantly, our community will help you discover what you are good at and what you love to do—and help you find a way to turn your passion into a fulfilling, world-changing career. So get ready for the ride of your life with an extraordinary group of fellow students who will become your closest friends and professors who will mentor and guide you on your journey—all in a growing and vibrant city filled with learning and career opportunities. -

2018 Mid-South Men's Bowling Championships Bracket

2018 Mid South Conference Team Championship Men 4 Campbellsville University (4) - 173,151,210,149,189,143 Sat 2/24/2018 10:45 am Union College (5) - 167,145,213,225,232,167,172 23-24 (4 5 Union College (5) - 179,185,176,187,150,202 Sat 2/24/2018 2:15 pm Union College (5) - 209,153,158,154,207,173,155 13-14 (13 8 Bethel University (8) - 182,194,150,185,181 Sat 2/24/2018 9:00 am Bethel University (8) - 170,170,186,194 9-10 (1 9 Cumberland University (9) - 171,135,167,165,159 Sat 2/24/2018 10:45 am Bethel University (8) - 147,176,215,193,221,203,164 19-20 (5 1 University of Pikeville (1) - 158,167,171,159 Sun 2/25/2018 9:00 am (17 Martin Methodist College (2) - 215,211,174,162,241,222 19-20 Sun 2/25/2018 12:30 pm 3 Lindsey Wilson College (3) - 180,194,156,216,165,164,164 (20 Martin Methodist College (2) 21-22 Winner Sat 2/24/2018 10:45 am (6 Life University (6) - 154,178,187,172,203,151 Union College (5) - 158,209,206,179,175,211 15-16 (Winner 19) 6 Life University (6) - 137,165,203,185,207,241 Sat 2/24/2018 9:00 am Life University (6) - 173,196,162,183,172,164,178 13-14 (2 11 Shawnee State University (11) - 169,195,160,156,171,129 Sat 2/24/2018 2:15 pm Martin Methodist College (2) - 183,197,179,189,160,161,205 9-10 (14 7 University of the Cumberlands (7) - 154,172,165,212,160 Sat 2/24/2018 9:00 am Tennessee Wesleyan University (10) - 136,167,184,147,172,140 17-18 (3 10 Tennessee Wesleyan University (10) - 159,214,186,149,180 Sat 2/24/2018 10:45 am Martin Methodist College (2) - 144,227,223,160,212,182 11-12 (7 2 Martin Methodist College -

Nulldfr 2018 Report

Image description. Cover Image End of image description. NATIONAL CENTER FOR EDUCATION STATISTICS What Is IPEDS? The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) is a system of survey components that collects data from about 7,000 institutions that provide postsecondary education across the United States. IPEDS collects institution-level data on student enrollment, graduation rates, student charges, program completions, faculty, staff, and finances. These data are used at the federal and state level for policy analysis and development; at the institutional level for benchmarking and peer analysis; and by students and parents, through the College Navigator (http://collegenavigator.ed.gov), an online tool to aid in the college search process. For more information about IPEDS, see http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds. What Is the Purpose of This Report? The Data Feedback Report is intended to provide institutions a context for examining the data they submitted to IPEDS. The purpose of this report is to provide institutional executives a useful resource and to help improve the quality and comparability of IPEDS data. What Is in This Report? The figures in this report provide a selection of indicators for your institution to compare with a group of similar institutions. The figures draw from the data collected during the 2017-18 IPEDS collection cycle and are the most recent data available. The inside cover of this report lists the pre-selected comparison group of institutions and the criteria used for their selection. The Methodological Notes at the end of the report describe additional information about these indicators and the pre-selected comparison group. -

Ferry 2020 CV

Megan M. Ferry Professor of Chinese and Asian Studies Modern Languages and Literatures Department Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 (518) 388-7104 [email protected] EDUCATION Washington University-St. Louis, Comparative Literature (Chinese and German languages and literatures), PhD August 1998. Dissertation: "Chinese Women Writers of the 1930s and Their Critical Reception." Washington University-St. Louis, Comparative Literature, MA, Fall, 1993. Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Asian Studies/German, BA, cum laude, 1989. International Study Inter-University Program (National Taiwan University), Taipei, advanced Chinese language study,1989-1990. University of Frankfurt, Germany, DAAD Scholarship, film studies, Summer, 1989. Beijing Normal University, China, Chinese language study, 1987-1988. Tunghai University, Taichung, Taiwan, Chinese language study, Summer, 1987. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Chair, Modern Languages and Literatures Department, Union College, 2016-2020 Professor of Chinese, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, Union College, September 2017; Associate Professor, Union College 2005-2017 Visiting faculty, Uninter, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2008-2009 Luce Junior Professor of Chinese and East Asian Studies, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, Union College, 1999-2005 Lecturer, Department of Russian, Eurasian, East Asian Languages and Cultures, Emory University, 1998-1999 Visiting Research Fellow, Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, 1995-1997 Instructor and teaching assistant, Comparative Literature Program, Washington University in St. Louis, 1992-1998 RESEARCH INTERESTS • Gender and sexuality • Global China vis-à-vis • Foreign language • Media studies China-Africa-Latin advocacy and policy • Modern Chinese literature, American relations film and culture • Dams and development • Asian American film • Chinese language pedagogy PUBLICATIONS ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7471-0863 BOOKS Chinese Women Writers and Modern Print Culture, Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2018. -

October 2012 ERA Bulletin.Pub

The ERA BULLETIN - OCTOBER, 2012 Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 55, No. 10 October, 2012 The Bulletin NEW YORK & QUEENS CARS QUIT 75 YEARS AGO Published by the Electric The first northern Queens surface transit depend on short-haul business instead. Railroaders’ Association, horse car line was Dutch Kills (31st Street), Deficits, which had been increasing for sev- Incorporated, PO Box 3323, New York, New which started operating in 1869. Within a few eral years, rose rapidly during and after York 10163-3323. years, several small horse car lines provided World War I because of the rising cost of la- service. They were leased and merged into bor and materials. But Mayor Hylan and the the Steinway Railway Company, which was other city officials insisted on keeping the For general inquiries, incorporated March 30, 1892. five-cent fare. contact us at bulletin@ erausa.org or by phone NY&Q’s predecessor started operating the In the early 1920s, IRT, which subsidized at (212) 986-4482 (voice Calvary Line in 1874. When the New York & NY&Q, was on the verge of bankruptcy, but mail available). ERA’s Queens County Railway Company was incor- was able to remain solvent by reducing its website is porated on September 16, 1896, it bought work force. It converted more than a thou- www.erausa.org. the Steinway Railway Company. In 1903, the sand cars to MUDC (Multiple Unit Door Con- Editorial Staff: Interborough Rapid Transit Company as- trol) and installed turnstiles in most of the Editor-in-Chief: sumed control of NY&Q by buying the majori- stations. -

Fall 2016 Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life Scholarship Report

FALL 2016 OFFICE OF FRATERNITY AND SORORITY LIFE SCHOLARSHIP REPORT IFC Active Members Active Member GPA New Members New Member GPA Organization Totals* Organization GPA 1 Alpha Delta Phi 33 2.920 12 2.676 49 2.830 2 Alpha Epsilon Pi 99 3.047 30 2.728 129 2.977 3 Alpha Tau Omega 139 3.017 48 2.743 187 2.948 4 Beta Theta Pi 73 2.935 30 2.932 105 2.906 5 Chi Phi 82 2.980 26 3.035 121 2.926 6 Delta Chi 53 2.934 21 2.608 74 2.837 7 Delta Tau Delta 97 2.958 20 2.745 117 2.922 8 Kappa Alpha 126 3.000 38 2.589 164 2.906 9 Kappa Sigma 107 3.004 30 2.718 147 2.936 10 Phi Delta Theta 139 2.813 46 2.791 185 2.808 11 Phi Gamma Delta (FIJI) 68 3.128 26 2.943 94 3.078 12 Phi Kappa Psi 55 2.952 7 2.934 75 2.944 13 Phi Kappa Tau 97 2.943 28 2.587 126 2.877 14 Phi Sigma Kappa 89 2.768 15 2.855 104 2.780 15 Pi Kappa Alpha 182 2.996 53 2.895 238 2.970 16 Pi Kappa Phi 116 3.146 41 2.921 157 3.087 17 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 66 2.867 35 2.627 109 2.777 18 Sigma Phi Epsilon 97 3.095 32 2.803 129 3.029 19 Sigma Pi 64 3.088 19 2.856 89 3.030 21 Theta Chi 136 3.097 40 2.853 186 3.033 22 Zeta Beta Tau 101 3.053 24 2.673 125 2.980 Grand Totals 2019 2.994 621 2.787 2710 2.940 MGC Active Members Active Member GPA New Members New Member GPA Organization Totals* Organization GPA 1 alpha Kappa Delta Phi 8 3.028 2 3.081 12 3.031 2 Kappa Delta Chi 14 2.850 -- -- 17 2.898 3 Lambda Theta Alpha 12 2.306 -- -- 12 2.306 4 Lambda Theta Phi 7 2.037 -- -- 7 2.037 5 Omega Phi Beta 11 2.954 -- -- 11 2.954 6 Phi Iota Alpha 18 2.291 13 2.748 31 2.490 7 Sigma Beta Rho 10 3.049 -- -- 10 -

Brooklyn and the Bicycle

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2013 Brooklyn and the Bicycle David V. Herlihy How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/671 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Bikes and the Brooklyn Waterfront: Past, Present, and Future Brooklyn and the Bicycle by David V. Herlihy Across the United States, cycling is flourishing, not only as a recreational activity but also as a “green” and practical means of urban transportation. The phenomenon is particularly pronounced in Brooklyn, a large and mostly flat urban expanse with a vibrant, youthful population. The current national cycling boom encompasses new and promising developments, such as a growing number of hi-tech urban bike share networks, including Citi Bike, set to launch in New York City in May 2013. Nevertheless, the present “revival” reflects a certain historical pattern in which the bicycle has swung periodically back into, and out of, public favor. I propose to review here the principal American cycling booms over the past century and a half to show how, each time, Brooklyn has played a prominent role. I will start with the introduction of the bicycle itself (then generally called a “velocipede” from the Latin for fast feet), when Brooklyn was arguably the epicenter of the nascent American bicycle industry. 1 Bikes and the Brooklyn Waterfront: Past, Present, and Future Velocipede Mania The first bicycle craze, known then as “velocipede mania,” struck Paris in mid- 1867, in the midst of the Universal Exhibition. -

SUNY New Paltz Recognized Fraternities and Sororities Updated September 2020

SUNY New Paltz Recognized Fraternities and Sororities Updated September 2020 Inter-Fraternity Council • Alpha Epsilon Pi Fraternity (Nu Rho Chapter) • Alpha Phi Delta Fraternity* (Recognized Interest Group/Colony) • Kappa Delta Phi National Fraternity (Alpha Gamma Chapter) • Pi Alpha Nu Fraternity (Gamma Chapter) • Tau Kappa Epsilon Fraternity (Sigma Nu Chapter) Latino Greek Council - LGC • Chi Upsilon Sigma National Latin Sorority, Inc. (Alpha Pi Chapter) • Hermandad de Sigma Iota Alpha, Inc. (Gamma Chapter) • L:ambda Alpha Upsilon Fraternity, Inc.** (Provisional Interest Group) • Lambda Pi Upsilon Sorority, Inc. (Omicron Chapter) • Lambda Sigma Upsilon Latino Fraternity, Inc. (Guarionex Chapter) • Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc. (Pi Chapter) • Omega Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. (Beta Chapter) • Phi Iota Alpha Latino Fraternity, Inc. (Gamma Chapter) • Sigma Lambda Upsilon Sorority, Inc. (Alpha Mu Chapter) Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) • Alpha Kappa Phi Agonian Sorority (Kappa Chapter) • Kappa Delta Phi National Affiliated Sorority (Kappa Alpha Gamma Chapter) • MALIK Fraternity, Inc. (Ra Kingdom) • Mu Sigma Upsilon Sorority, Inc. (Orisha Chapter) • Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi Sorority* (Recognized Interest Group/Colony) National Panhellenic Conference - NPC • Alpha Epsilon Phi National Sorority (Phi Phi Chapter) • Sigma Delta Tau National Sorority (Gamma Nu Chapter) National Pan Hellenic Council - NPHC • Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. (Xi Mu Chapter) • Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. (Sigma Eta Chapter) • Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. (Omicron Kappa Chapter) • Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. (Kappa Mu Chapter) • Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. (Alpha Mu Chapter) *Denotes Recognized Interest Group, has full University recognition, awaiting national charter **Denotes Provisional Interest Group, seeking full University recognition . -

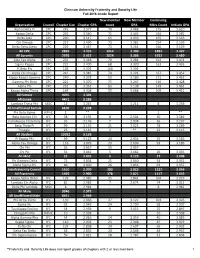

Fall 2016 FSL Grade Report

Clemson University Fraternity and Sorority Life Fall 2016 Grade Report New member New Member Continuing Organization Council Chapter Size Chapter GPA count GPA Mbrs Count Initiate GPA Alpha Delta Pi CPC 245 3.577 70 3.488 175 3.610 Kappa Delta CPC 235 3.540 71 3.445 164 3.581 Delta Zeta CPC 230 3.517 65 3.439 165 3.546 Chi Omega CPC 227 3.490 73 3.382 154 3.539 Delta Delta Delta CPC 229 3.447 73 3.261 156 3.529 All CPC 2895 3.433 1014 3.309 1881 3.497 All Sorority 2976 3.422 1024 3.306 1952 3.480 Zeta Tau Alpha CPC 232 3.418 70 3.281 162 3.474 Sigma Kappa CPC 231 3.400 68 3.320 163 3.433 Pi Beta Phi CPC 168 3.391 168 3.391 Alpha Chi Omega CPC 241 3.385 74 3.224 167 3.452 Kappa Kappa Gamma CPC 240 3.378 69 3.186 171 3.452 Gamma Phi Beta CPC 221 3.370 75 3.247 146 3.428 Alpha Phi CPC 232 3.351 83 3.138 149 3.462 Kappa Alpha Theta CPC 164 3.308 55 3.068 109 3.421 All Female 9076 3.301 All Greek 4471 3.283 Lambda Theta Phi MGC 12 3.243 4 3.211 8 3.258 All Unaffiliated Female 6100 3.238 Phi Beta Sigma NPHC 1 ** 1 ** Beta Upsilon Chi IFC 38 3.195 8 2.504 30 3.382 FarmHouse Fraternity IFC 33 3.176 7 2.938 26 3.237 Beta Theta Pi IFC 99 3.155 21 3.025 78 3.189 Triangle IFC 25 3.142 2 ** 23 3.115 All Student 19022 3.133 Pi Kappa Phi IFC 99 3.123 24 2.931 75 3.185 Alpha Tau Omega IFC 116 3.076 23 2.606 93 3.186 Chi Phi IFC 35 3.057 35 3.057 Chi Psi IFC 31 3.042 5 3.082 26 3.035 All MGC 22 3.035 5 3.125 17 3.008 Phi Gamma Delta IFC 75 3.034 21 3.040 54 3.032 Alpha Sigma Phi IFC 89 3.000 26 2.856 63 3.057 Interfraternity Council 1510 2.999 383 2.823