The Future of Wotus: Examining the Role of States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North American Benthological Society 2011 Annual Meeting

North American Benthological Society 2011 Annual Meeting Responding to the Global Water Crisis Rhode Island Convention Center Providence, Rhode Island, USA 22–26 May 2011 Program Book Contents NABS 2011 Program Committee .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 NABS 2011 Elected Officers .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Meeting Sponsors ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Support ALS Research..................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Special Events and Activities .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 The Great Debate...................................................................................................................................................................................................1 -

Extensions of Remarks E745 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

June 2, 2017 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E745 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS HONORING THE LIFE OF ALMON Chief Miller has dedicated his entire career As Delaware County grew, the parish school WILLIAM MARTIN to the people of Gonzales, and our commu- opened its doors in 1919 and soon served nities on the central coast of California. His many families. HON. JAMES B. RENACCI career began in the Monterey County The Saint Laurence School is still an award- OF OHIO Sherriff’s Explorer Program in 1978 where winning institution in the community, com- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Chief Miller achieved the rank of Captain, the mitted to academic excellence. The parish highest rank in that program. After completing Friday, June 2, 2017 school seeks to integrate Catholic values of the Explorer Program, Chief Miller joined the service and respect. With the dedication and Mr. RENACCI. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Gonzales Police Department (GPD), first as a devotion of nearly ten pastors in the last hun- pay tribute to the life of Sergeant Almon Wil- reserve officer, and then a full-time officer in dred years, the Saint Laurence Parish is proud liam Martin, father of William Martin, Craig 1985. After being recognized as the Depart- to serve nearly two thousand registered Martin, and Leslie Lederer and husband of Au- ment Officer of the Year in 1987 and 1991, households in the Upper Darby and drey June Martin. Sergeant Martin dedicated Chief Miller was promoted to the rank of Ser- Havertown areas today. his life to serving his community and our Na- geant in 1992. -

CDIR-2018-10-29-VA.Pdf

276 Congressional Directory VIRGINIA VIRGINIA (Population 2010, 8,001,024) SENATORS MARK R. WARNER, Democrat, of Alexandria, VA; born in Indianapolis, IN, December 15, 1954; son of Robert and Marge Warner of Vernon, CT; education: B.A., political science, George Washington University, 1977; J.D., Harvard Law School, 1980; professional: Governor, Commonwealth of Virginia, 2002–06; chairman of the National Governor’s Association, 2004– 05; religion: Presbyterian; wife: Lisa Collis; children: Madison, Gillian, and Eliza; committees: Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Budget; Finance; Rules and Administration; Select Com- mittee on Intelligence; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2008; reelected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2014. Office Listings http://warner.senate.gov 475 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–2023 Chief of Staff.—Mike Harney. Legislative Director.—Elizabeth Falcone. Communications Director.—Rachel Cohen. Press Secretary.—Nelly Decker. Scheduler.—Andrea Friedhoff. 8000 Towers Crescent Drive, Suite 200, Vienna, VA 22182 ................................................... (703) 442–0670 FAX: 442–0408 180 West Main Street, Abingdon, VA 24210 ............................................................................ (276) 628–8158 FAX: 628–1036 101 West Main Street, Suite 7771, Norfolk, VA 23510 ........................................................... (757) 441–3079 FAX: 441–6250 919 East Main Street, Richmond, VA 23219 ........................................................................... -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 14-1504 IN T HE Supreme Court of the United States ROBERT J. WITTMAN, BOB GOODLATTE, RANDY FORBES, MORGAN GRIFFITH, SCOTT RIGELL, ROBERT HURT, DAVID BRAT, BARBARA COMSTOCK, ERIC CANTOR & FRANK WOLF, Appellants, v. GLORIA PERSONHUBALLAH & JAMES FARKAS, Appellees. On Appeal From The United States District Court For The Eastern District Of Virginia BRIEF OPPOSING APPELLEES’ MOTIONS TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM MICHAEL A. CARVIN Counsel of Record JOHN M. GORE JONES DAY 51 Louisiana Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 (202) 879-3939 [email protected] August 4, 2015 Counsel for Appellants Robert J. Wittman, Bob Goodlatte, Randy J. Forbes, Morgan Griffith, Scott Rigell, Robert Hurt, David Brat, Barbara Comstock, Eric Cantor & Frank Wolf i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii BRIEF OPPOSING APPELLEES’ MOTIONS TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM .............................. 1 I. APPELLEES FAIL TO REHABILI- TATE THE MAJORITY’S MISAPPLI- CATION OF EASLEY AND ALABAMA ......... 4 II. APPELLEES FAIL TO REHABILI- TATE THE NARROW TAILORING ERRORS ......................................................... 10 III. APPELLANTS HAVE STANDING ............... 11 III. CONCLUSION ............................................... 13 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) CASES Ala. Leg. Black Caucus v. Ala., 135 S. Ct. 1257 (2015) ............................ 1, 4, 10, 11 Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996) ................................................ 9 Cantor v. Personhuballah, 135 S. Ct. 1699 (2015) ............................................ 3 Easley v. Cromartie, 532 U.S. 234 (2001) .......................................passim Hall v. Virginia, 276 F. Supp. 2d 528 (E.D. Va. 2003) ................... 11 Hollingsworth v. Perry, 133 S. Ct. 2652 (2013) .................................... 11, 12 In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978) ................................................ 4 Johnson v. Mortham, 915 F. Supp. 1529 (N.D. Fla. 1995) .............. -

Conversations with Bill Kristol

Conversations with Bill Kristol Guest: Ronald Brownstein, Senior Editor, The Atlantic Senior Political Analyst, CNN Taped June 27, 2018 Table of Contents I: Red America and Blue America 0:15 – 47:07 II: 2018 and 2020 47:07– 1:24:19 I: Red America and Blue America (0:15 – 47:07) KRISTOL: Hi, I’m Bill Kristol. Welcome to CONVERSATIONS. I’m joined today by Ron Brownstein, senior editor at The Atlantic, senior political analyst at CNN. In my opinion, one of the best analysts of American politics. BROWNSTEIN: Thank you, Bill, good to be here. KRISTOL: A rare combination of detailed, granular understanding of electoral matters and the big historical sweep. So, I’ve now put a big burden on you here… BROWNSTEIN: Thank you, thank you. Well, we are living in a big – we are in a big sweep right now, right. KRISTOL: …to live up to this introduction. BROWNSTEIN: Yes. KRISTOL: So, I think we talked a year ago. Now we’re – what? – more than a year and a half out from the election. BROWNSTEIN: Yeah. KRISTOL: Only four or five months till November 2018. What’s changed over the last year? We analyzed 2016 a little bit last time. So, where are we now, here in June-July of 2018? 2017 – what are we in? 2018. BROWNSTEIN: 2018. I feel like every crevice, every fissure that we talked about in 2017 and that we saw in 2016 may be even deeper in 2018. To me, the Trump presidency has said more about the country than about him. -

Revolving Congress

Revolving Congress: The Revolving Door Class of 2019 Flocks to K Street Nearly Two Thirds of Former Members of 115th Congress Working Outside Politics and Government Have Picked Up Lobbying or Strategic Consulting Jobs By Alan Zibel, Public Citizen Research Director May 30, 2019 – Nearly two-thirds of recently retired or defeated U.S. lawmakers now working outside politics have landed jobs influencing federal policy, providing further evidence that members of Congress continue to spin through Washington’s revolving door at astonishing rates. Public Citizen analyzed the post-Congress employment activities of the 115th Congress, which started in 2017 and concluded on Jan. 3 of this year. Of the former members who have found new jobs outside of government and politics, 59% (26 of 44) were working for lobbying firms, consulting firms, trade groups or business groups working to influence federal government activities. Many others were working in television (14%) law (9%) corporate jobs (7%) academia (7%) or state-level groups (5%). Category Count Pct. Lobbying/consulting 22 50% Business/Trade Group (Federal) 4 9% Television 6 14% Law 4 9% Academia 3 7% Corporate 3 7% Business/Trade Group (State) 2 5% Subtotal Federal Influence 26 59% Grand Total 44 100% Sources: Roll Call, Public Citizen research Over the past two decades, concern has been building about members of Congress who flock to lobbying firms or trade groups after retiring or losing their seats. These revolving-door lawmakers cash in on their connections by representing wealthy special interests who can afford to pay top dollar for insider influence. Revolving Congress Public Citizen In the 115th Congress, there have been several notable examples of the revolving door activity, with two of the largest Washington, D.C. -

115Th Congress 281

VIRGINIA 115th Congress 281 NJ, 1990; Ph.D., in economics, American University, Washington, DC, 1995; family: wife, Laura; children: Jonathan and Sophia; committees: Budget; Education and the Workforce; Small Business; elected to the 114th Congress on November 4, 2014; reelected to the 115th Congress on November 8, 2016. Office Listings http://www.brat.house.gov facebook: representativedavebrat twitter: @repdavebrat 1628 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ........................................... (202) 225–2815 Chief of Staff.—Mark Kelly. FAX: 225–0011 Scheduler.—Grace Walt. ¨ Legislative Director.—Zoe O’Herin. Press Secretary.—Julianna Heerschap. 4201 Dominion Boulevard, Suite 110, Glen Allen, VA 23060 ................................................ (804) 747–4073 9104 Courthouse Road, Room 249, Spotsylvania, VA 22553 .................................................. (540) 507–7216 Counties: AMELIA, CHESTERFIELD (part), CULPEPER, GOOCHLAND, HENRICO (part), LOUISA, NOTTOWAY, ORANGE, POWHATAN, AND SPOTSYLVANIA (part). Population (2010), 727,366. ZIP Codes: 20106, 20186, 22407–08, 22433, 22508, 22534, 22542, 22551, 22553, 22565, 22567, 22580, 22701, 22713– 14, 22718, 22724, 22726, 22729, 22733–37, 22740–41, 22923, 22942, 22947, 22957, 22960, 22972, 22974, 23002, 23015, 23024, 23038–39, 23058–60, 23063, 23065, 23067, 23083–84, 23093, 23102–03, 23112–14, 23117, 23120, 23129, 23139, 23146, 23153, 23160, 23222, 23224–30, 23233–38, 23294, 23297, 23824, 23832–33, 23838, 23850, 23922, 23930, 23955, 23966 *** EIGHTH DISTRICT DONALD S. BEYER, JR., Democrat, of Alexandria, VA; born in the Free Territory of Tri- este, June 20, 1950; education: B.A., Williams College, MA, 1972; professional: Ambassador to Switzerland and Liechtenstein 2009–13; 36th Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, 1990–98; co- founder of the Northern Virginia Technology Council; former chair of Jobs for Virginia Grad- uates; served on Board of the D.C. -

2021 Virtual Summer Undergraduate Research Conference Abstract Book

GoodwinVirtual Hall | July July 29,26, 20212018 || 9:00am9am-4pm - 4:30pm www.research.undergraduate.vt.edu Contents WELCOME FROM ASSOCIATE VICE PROVOST FOR UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION, DR. JILL SIBLE 3 WELCOME FROM DIRECTOR OF THE OFFICE OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, KERI SWABY 4 SUMMER RESEARCH PROGRAMS AT VT 5 - 8 INFORMATIONAL BOOTHS 9 ABSTRACTS (ALPHABETICAL) 10 Jill C. Sible, Ph.D. Associate Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education, Professor of Biological Sciences Welcome With great enthusiasm, I welcome all to the 2021 Summer Undergraduate Research Conference at Virginia Tech. This year is particularly exciting to feature both the work of students conducting research remotely as well those who were able to join us in person. Many students presenting today, have spent ten or more weeks immersed in a research project. Summer affords undergraduates the opportunities to dedicate significant time and effort to the planning, execution and analysis of a research project. They have also had the chance to become authentic members of research teams by working with faculty, graduate students, postdoctoral fellows and research staff. Many thanks to all who have mentored undergraduates this summer. Your commitment to undergraduate research is always commendable, and especially this year given the extra challenges you overcame to offer safe and engaging research opportunities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Virginia Tech is pleased to offer these summer experiences not only to our own students, but also to undergraduates from all over the country. We hope that you have enjoyed your time working with Virginia Tech research teams, and we appreciate the diversity of ideas and cultures that you have brought to our research programs. -

Officers, Officials, and Employees

CHAPTER 6 Officers, Officials, and Employees A. The Speaker § 1. Definition and Nature of Office § 2. Authority and Duties § 3. Power of Appointment § 4. Restrictions on the Speaker’s Authority § 5. The Speaker as a Member § 6. Preserving Order § 7. Ethics Investigations of the Speaker B. The Speaker Pro Tempore § 8. Definition and Nature of Office; Authorities § 9. Oath of Office §10. Term of Office §11. Designation of a Speaker Pro Tempore §12. Election of a Speaker Pro Tempore; Authorities C. Elected House Officers §13. In General §14. The Clerk §15. The Sergeant–at–Arms §16. The Chaplain §17. The Chief Administrative Officer D. Other House Officials and Capitol Employees Commentary and editing by Andrew S. Neal, J.D. and Max A. Spitzer, J.D., LL.M. 389 VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:53 Dec 04, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00389 Fmt 8875 Sfmt 8875 F:\PRECEDIT\WORKING\2019VOL02\2019VOL02.PAGETURN.V6.TXT 4473-B Ch. 6 PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE §18. The Parliamentarian §19. General Counsel; Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group §20. Inspector General §21. Legislative Counsel §22. Law Revision Counsel §23. House Historian §24. House Pages §25. Other Congressional Officials and Employees E. House Employees As Party Defendant or Witness §26. Current Procedures for Responding to Subpoenas §27. History of Former Procedures for Responding to Subpoenas F. House Employment and Administration §28. Employment Practices §29. Salaries and Benefits of House Officers, Officials, and Employees §30. Creating and Eliminating Offices; Reorganizations §31. Minority Party Employees 390 VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:53 Dec 04, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00390 Fmt 8875 Sfmt 8875 F:\PRECEDIT\WORKING\2019VOL02\2019VOL02.PAGETURN.V6.TXT 4473-B Officers, Officials, and Employees A. -

May the Best Woman Win: Two Women Compete for Virginia’S 10Th Congressional District by Sarah Sem

May the Best Woman Win: Two Women Compete for Virginia’s 10th Congressional District By Sarah Sem In just 58 days in Virginia’s 10th Congressional District, a two-time Democratic state senator and the Republican incumbent will face off in what the New York Times calls “one of the most hotly contested races in the country.” With 2018 already being called the “Year of the Woman,” Virginia’s 10th Congressional District midterm race is worth watching. Incumbent Rep. Barbara Comstock (VA-10) will be defending her seat against another female politico, Virginia State Sen. Jennifer Wexton, in a district the Cook Political Report identifies as Lean Democratic. The district itself is gaining national attention, especially since the governorship and the House of Delegates went Democrat in 2017 and it is one of 23 seats under Republican control that Democrats will attempt to flip in order to control the House. According to local Virginian paper the Loudoun Times-Mirror, half of the voters in Virginia’s 10th Congressional District identify as independents, with whom Wexton currently leads by nine points. Additionally, the New York Times said the district has “one of the highest concentration of college graduates in a Republican-held seat” and has a large immigrant presence as well. Fortunately for Comstock, one of her strengths is in constituent services and showing up at Eid festivals, Diwali, Korean National Day and Pakistan Day. However, some constituents are not happy with her conduct at the events. Grace Wolf Cunningham, a Democrat, Korean-American, and Herndon Town Councillor, told the New York Times that Comstock often comes to events with a canned statement and little else. -

President Trump's First Term

The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research Volume 5 Article 1 2-15-2020 President Trump’s First Term: The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research, Volume 5 Robert X. Browning Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Browning, Robert X. (2020) "President Trump’s First Term: The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research, Volume 5," The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: Vol. 5 , Article 1. Available at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol5/iss1/1 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. President Trump’s First Term: The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research, Volume 5 Cover Page Footnote To purchase a hard copy of this publication, visit: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/titles/format/ 9781557538826 This article is available in The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol5/iss1/1 “For almost 25 years I have watched the C-SPAN Video Library evolve into the nonpareil of data on congressional institutional behavior. Most instructors of the legislative process have utilized the C-SPAN’s material in the classroom with great success. Here, in this volume, Robert X. Browning once again demonstrates the myriad ways scholars can advance conventional wisdom on the U.S. Congress and institutions with the C-SPAN Video Library’s seemingly unlimited data. Debates, hearings, and floor speeches are just a few fascinating resources that are brilliantly used in this volume. -

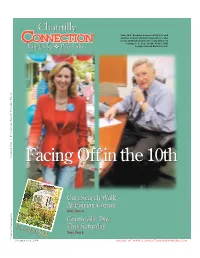

Chantilly State Del

State Del. Barbara Comstock (R-34) and Fairfax County District Supervisor John Foust (D-Dranesville) are competing for retiring U.S.Congressional Rep. Frank District Wolf’s 10thseat. ChantillyChantilly ❖❖ FairFair LakesLakes FairFair OaksOaks Sports, Page 8 Page Sports, ❖ ❖ Classifieds, Page 10 10 Page Classifieds, ❖ ❖ News,News, PagesPages 2-32-3 Calendar, Page 12 12 Page Calendar, FacingFacing OffOff inin thethe 10th10th Inside HomeLifeStyleHomeFall 2014 LifeStyle CureSearchCureSearch WalkWalk AtAt FairfaxFairfax CornerCorner ❖ 1 News,News, PagePage 44 ❖ October 9-15, 2014 CentrevilleCentreville DayDay Chantilly Connection ThisThis SaturdaySaturday online at www.connectionnewspapers.com Chantilly Fair Oaks ❖ FairFair LakesLakes News,News, PagePage 55 Lwowwc.Calo nMnecdtiioa nCNoenwsnpeacpetriso.cno mLLC onlCinhaen tailtl yw Cwonwn.cecotionnn e❖c HometionLifenewStylespap Fallers 2.c0o14m ❖ 1 Home LifeStyleLifeStyle Photos Contributed Photos October 9-15, 2014 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Election 2014 Q&A WITH BARBARA COMSTOCK Q: What are some of your favorite restaurants in your district? A: “We love The Old Brogue in Great Falls. It’s like Cheers, where everybody knows your name. Also The Tavern in Great Falls and J. Gilberts in Comstock’s Comfort Zone McLean.” Q: What personal qualities do you have that make you the best candidate for this position? GOP candidate Barbara Comstock believes A: “All of my bosses would tell you this. I work very hard. As a woman in law and politics, sometimes I’ve had to work twice as hard as my male a woman’s place is in the House ... of Representatives. counterparts. Also, I am a problem-solver. When we were out campaigning, Congressman Wolf would introduce me to voters as a problem- By Victoria Ross Facebook, and Bobbie Kilberg, solver, someone who can get things done.” The Connection president and CEO of the North- Q: What are you most proud of? ern Virginia Technology Council.