Cover Page, Table of Contents and Others

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Qualification Documentation

DEM & Associates Holding PRE-QUALIFICATION DOCUMENTATION October, 2013 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 ORGANIZATION 2.0 TALENT 1.1 DEM & Associates Holding 3 2.1 Organizational Chart 8 1.2 DEM Geosciences 4 1.3 Terra Drill International 5 1.4 Saudi Foundations 6 1.5 Terra Gunhan Co. 7 3.0 Services 4.0 EQUIPMENT 3.1 Mining 9 4.1 Mining Equipment 35 3.2 Program Management 15 4.2 Geotechnical equipment 39 3.3 Marine Engineering Services 17 3.4 Geotechnical Contracting 19 5.0 Credentials 46 6.0 CONTACT DETAILS 59 July 7, 2014 2 1.0 ORGANIZATION 1.1 DEM & Associates Holding DEM & Associates Holding sal DEM Geosciences Terra Gunhan Co. sal (DEMG) sarl (TERGU) Saudi Terra Drill DEM Geosciences Foundations LTD International LTD Georgia (SF) (TDI) DEM & Associates Holding sal is the mother company for DEM Geosciences sal (DEMG), DEM Geosciences Georgia, Terra Drill International ltd (TDI), Saudi Foundations (SF) and Terra Gunhan Co. sarl (TERGU). The Group provides complete solutions to the mining industry as well as geotechnical contracting and consultancy across East Europe, Eurasia and the Middle East. We believe in working in close partnership with clients to provide a professional and cost effective service at all levels. Our experience, supported by highly qualified team of engineers and geologists, have the skills and experience required to provide professional results on projects of all scales. July 7, 2014 3 1.0 ORGANIZATION 1.2 DEM Geosciences sal (DEMG) DEMG has been created to utilize the resources of its subsidiaries, namely TerraDrill Intl. -

English and Translated to Arabic

Knowledge partner: Constructing the Arab Region’s Engagement in the Emerging Global Future Policy Recommendations Beirut Institute Summit Edition II Abu Dhabi, May 2018 The 2017 A.T. Kearney Foreign Direct Investment Confidence Index: Glass Half Full 1 Disclaimer The views expressed by speakers, presenters, and moderators of the second edition of the Beirut Institute Summit Edition II are their own. This document was originally written in English and translated to Arabic. Beirut Institute Summit Edition II, Abu Dhabi, May 2018 Executive Summary Beirut Institute Summit Edition II is a driving force focused on mobilizing a rich diversity of minds to think collaboratively and innovatively about the future of the Arab region. In May 2018, we convened Beirut Institute Summit Edition II in Abu Dhabi, building on the success of the first Beirut Institute Summit Edition I that was held in late 2015. The Summit took place in the context of a period of rapid and historic transformation in the Arab region and globally. Given the disruptive geopolitical, technological and socio-economic changes underway, our deliberations centered on designing practical policy recommendations for constructing the Arab region’s engagement in the emerging global future. The final recommendations constitute five fundamental strategic imperatives: 1. Strengthen the Forces of Order: Systematically create the conditions and capabilities necessary for sustainable regional stability 2. Accelerate Connected Regional Economic Development: Intensify Arab-led investment in regional economic development and integration 3. Promote Whole-Of-Nation Good Governance: Expand models of good governance to better integrate individuals and local communities 4. Empower the Diverse People of the Arab Region: Activate a tolerant, inclusive, future- oriented vision for the Arab Region 5. -

Geohab Core Research Project

GEOHAB CORE RESEARCH PROJECT: HABs IN STRATIFIED SYSTEMS “Advances and challenges for understanding physical-biological interactions in HABs in Strati fied Environments” A Workshop Report ISSN 1538 182X GEOHAB GLOBAL ECOLOGY AND OCEANOGRAPHY OF HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS GEOHAB CORE RESEARCH PROJECT: HABs IN STRATIFIED SYSTEMS AN INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME SPONSORED BY THE SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ON OCEANIC RESEARCH (SCOR) AND THE INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION (IOC) OF UNESCO Workshop on “ADVANCES AND CHALLENGES FOR UNDERSTANDING PHYSICAL-BIOLOGICAL INTERACTIONS IN HABs IN STRATIFIED ENVIRONMENTS” Edited by: M.A. McManus, E. Berdalet, J. Ryan, H. Yamazaki, J. S. Jaffe, O.N. Ross, H. Burchard, I. Jenkinson, F.P. Chavez This report is based on contributions and discussions by the organizers and participants of the workshop. TABLE OF CONTENTS This report may be cited as: GEOHAB 2013. Global Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms, GEOHAB Core Research Project: HABs in Stratified Systems.W orkshop on "Advances and Challenges for Understanding Physical-Biological Interactions in HABs in Stratified Environments." (Eds. M.A. McManus, E. Berdalet, J. Ryan, H. Yamazaki, J.S. Jaffe, O.N. Ross, H. Burchard and F.P. Chavez) (Contributors: G. Basterretxea, D. Rivas, M.C. Ruiz and L. Seuront) IOC and SCOR, Paris and Newark, Delaware, USA, 62 pp. This document is GEOHAB Report # 11 (GEOHAB/REP/11). Copies may be obtained from: Edward R. Urban, Jr. Henrik Enevoldsen Executive Director, SCOR Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of College -

Business Guide

TOURISM AGRIFOOD RENEWABLE TRANSPORT ENERGY AND LOGISTICS CULTURAL AND CREATIVE INDUSTRIES BUSINESS GROWTH OPPORTUNITIES IN THE MEDITERRANEAN GUIDE RENEWABLERENEWABLERENEWABLERENEWABLERENEWABLE CULTURALCULTURALCULTURALCULTURALCULTURAL TRANSPORTTRANSPORTTRANSPORTTRANSPORTTRANSPORT AGRIFOODAGRIFOODAGRIFOODAGRIFOODAGRIFOOD ANDANDAND ANDCREATIVE ANDCREATIVE CREATIVE CREATIVE CREATIVE ENERGYENERGYENERGYENERGYENERGY TOURISMTOURISMTOURISMTOURISMTOURISM ANDANDAND ANDLOGISTICS ANDLOGISTICS LOGISTICS LOGISTICS LOGISTICS INDUSTRIESINDUSTRIESINDUSTRIESINDUSTRIESINDUSTRIES GROWTH GROWTH GROWTH GROWTH GROWTH OPPORTUNITIES IN OPPORTUNITIES IN OPPORTUNITIES IN OPPORTUNITIES IN OPPORTUNITIES IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THE MEDITERRANEAN THE MEDITERRANEAN THE MEDITERRANEAN THE MEDITERRANEAN ALGERIA ALGERIA ALGERIA ALGERIA ALGERIA BUILDING AN INDUSTRY PREPARING FOR THE POST-OIL PROMOTING HERITAGE, EVERYTHING IS TO BE DONE! A MARKET OF 40 MILLION THAT MEETS THE NEEDS PERIOD KNOW-HOW… AND YOUTH! INHABITANTS TO BE OF THE COUNTRY! DEVELOPED! EGYPT EGYPT EGYPT REBUILD TRUST AND MOVE EGYPT SOLAR AND WIND ARE BETTING ON THE ARAB UPMARKET EGYPT PHARAONIC PROJECTS BOOMING WORLD’S CULTURAL THE GATEWAY TO AFRICA ON THE AGENDA CHAMPION AND THE MIDDLE EAST IN ISRAEL SEARCH FOR INVESTORS ISRAEL ACCELERATE THE EMERGENCE ISRAEL TAKE-OFF INITIATED! ISRAEL OF A CHEAPER HOLIDAY COLLABORATING WITH THE THE START-UP NATION AT THE OFFER ISRAEL WORLD CENTRE OF AGRITECH JORDAN FOREFRONT OF CREATIVITY LARGE PROJECTS… AND START-UPS! GREEN ELECTRICITY EXPORTS JORDAN JORDAN IN SIGHT JORDAN -

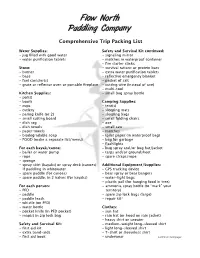

Comprehensive Trip Packing List

Comprehensive Trip Packing List Water Supplies: Safety and Survival Kit continued: - jug filled with good water - signaling mirror - water purification tablets - matches in waterproof container - fire starter sticks Stove: - survival rations or protein bars - burner - extra water purification tablets - base - reflective emergency blanket - fuel canister(s) - packet of salt - grate or reflector oven or portable fireplace - cutting wire (instead of axe) - multi-tool Kitchen Supplies: - small bug spray bottle - pot(s) - bowls Camping Supplies: - cups - tent(s) - cutlery - sleeping mats - paring knife (or 2) - sleeping bags - small cutting board - small folding chairs - dish rag - axe - dish towels - small saw - paper towels - matches - biodegradable soap - toilet paper (in waterproof bag) - FOOD (make a separate list/menu) - bag for garbage - flashlights For each kayak/canoe: - bug spray and/or bug hat/jacket - bailer or water pump - tarps and/or groundsheet - rope - spare straps/rope - sponge - spray skirt (kayaks) or spray deck (canoes) Additional Equipment/Supplies: if paddling in whitewater - GPS tracking device - spare paddle (for canoes) - bear spray or bear bangers - spare paddle, in 2 halves (for kayaks) - water-tight bags - plastic pail (for hanging food in tree) For each person: - ammonia spray bottle (to “mark” your - PFD territory) - paddle - spare zip lock bags (large) - paddle leash - repair kit* - whistle (on PFD) - water bottle Clothes: - pocket knife (in PFD pocket) - sun hat - map(s) in zip lock bag - rain hat (or hood on rain -

Ksenia Anske PO Box 55871 Seattle, WA 98155 [email protected] TUBE

Ksenia Anske PO Box 55871 Seattle, WA 98155 [email protected] TUBE: Trans-Urban Blitz-Express A novel by Ksenia Anske 153,144 words Anske / TUBE / 1 Chapter 1. Red Shoes The train was watching Olesya undress. She thought it shuddered under the carpet, thick purple carpet, felt the shudder through the soles of her shoes, new flats acquired for the tour in a boutique on Tverskaya, a red lacquer pair that cost half of her principal dancer salary, but it was worth it, dammit, it was worth it to spend— There it is again. A dragging laborious stretch ran through the casing of the machine as though it expanded and contracted, rushing out the air with a hiss. Olesya tore up her feet. Her heart thrummed. It can’t be. I’m just— She glanced out the window. They were standing. According to the large electronic clock it was 11:08 A.M. The train wasn’t due to depart for another five minutes. I wish we’d leave already. I don’t know if I can stand any more of this...whatever it is, are they checking the wheels? I hear Americans are never late, not like Russians. For us the concept of time doesn’t exist. I’m the only weirdo, always showing up before practice. Should’ve taken a shot of vodka like Natasha said. Now I’m hearing things that aren’t there. Anske / TUBE / 2 Olesya shook her head and continued to unpack. Her lucky charm—the TUBE toy train locomotive that she nicknamed Trubochka—the present her father gave her the year he died, the token of his memory she carried with her ever since, was already unwrapped and sitting on the foldout table, scuffed and scraped by a decade of life in pockets but still discernably chic for a mere toy, originally painted peachy cream, now faded to the shade of a healed scar. -

Boots and Shoes

COMPILERS NOTES The following is a faithful digitalization of volume VI of F.Y. Golding’s BOOTS AND SHOES. I have taken the liberty of using this original blank page to comment on the material within. Insofar as I was able, I have endeavoured to preserve the original appearance, formatting, kerning, spacing, etc,. of the original work. Sometime, however, this was simply not possible. The typefaces used in the original text are not precisely duplicated in any of the font sets to which I have access. Then too, the spacing between chapter, paragraph, and graphic elements is often inconsistent within the original text. Sometimes a chapter heading will be set an inch and a quarter below the edge of the page, sometime an inch and a half. Sometimes, using a given set of paragraph styles, a page would format almost to the exact word at the bottom margin...and then the next page would run over or come up substantially short. Nevertheless, I have preserved page numbers and the contents of those pages to fairly close extent. Beyond that, nothing has been added or subtracted from the text as it is contained in the original volumes in my possession. It is my fervent hope that this work will help to preserve the Trade and make this invaluable resource more accessible to those students seeking to learn from the past masters. DWFII BOOTS AND SHOES THEIR MAKING MANUFACTURING AND SELLING VOLUME VI BESPOKE BOOTMAKING J. BALL HANDSEWN BOOTMAKING H. ROLLINSON, A.B.S.I. BOOTS AND SHOES THEIR MAKING MANUFACTURE AND SELLING A WORK IN EIGHT VOLUMES DEALING WITH PATTERN CUTTING AND MAKING. -

Corporate Social Responsibility in Lebanon

LEBANESE TRANSPARENCY ASSOCI A TION Corporate Social Responsibility in Lebanon The Lebanese Transparency Association P.O. Box 05-005, Baabda , Lebanon Tel/Fax: 169-9-510590; 169-9515501 [email protected] www.transparency-lebanon.org The Lebanese Transparency Association PO Box 05 005 Baabda, Lebanon Telephone +169 9 510590 • Fax +169 9 515501 www.transparency-lebanon.org LEBANESE TRANSPARENCY ASSOCIATION Introduction Corporate social responsibility (CSR) at its best practice can be defined as the overall management process that accompanies all the efforts of an organization within the limits of a certain ethical conduct. CSR starts internally within the organization as a set of beliefs and values of all the human resource. In such a case the organization will naturally communicate those ethical values through: 1. Personal interaction level (Meetings, promotions, events, media gatherings) 2. Corporate communications (press releases, webpage, print communications, product labels, advertising campaigns, brand building strategies, corporate logo) In effect and as illustrated in Fig 1, these communicated beliefs will result in added trust towards the organizations’ overall image and will potentially increase business and sustain development in the long run. In the ideal case, CSR is conducted as part of and adapted to the business strategy and vision, which is normally defined by the top management. According to the St. Galler Management Concept (University of St. Gallen, Bleicher 1991), these principles should be realized by the strategical and operational management levels. The whole strategy is therefore conducted by the whole company and becomes a part of the company’s identity. To act socially responsible and to integrate CSR in a businesses’ strategy has eventually the aim of increasing sales revenues and achieving profits, as opposed to purely philanthropic actions. -

Work Handbook's

“ WO R K” HA N DBO O KS A S eries of Prac cal M nua s ti a l . Edit d b PA UL N HA L i o W e y . S UCK , Ed tor f ORK . u De cor a i n C ri i ‘VH I T ETV A SH IX G H o s e t o p omp s ng , A PER H A N G IN G PA I N T IN G et c Wi h 9 E . 7 n a v in s P , , t gr g and Dia ram s l s ost f ee l 2 d . s . —g . ; p r , . ontent s . Ou l r a nd Pain s P m l C C o ou t . ig ents . Oi s , D ie s V arnis e s et c . Too s u se b Pa in e s H w t r r , h , l d y t r . o o r m ix Oil Pain s . Dis em e or Te e a Pa in in W i e M t t p p r t g . h t wa s in and De co a in a. C ei in . P t a, R h g r t g l g ain ing oom . Pa e in a, R . Em b e is m en of Wa s a nd i in s p r g oom ll h t ll C e l g . kin n M n din Incl di R E Boot Ma g a d e g . -

Company Profile

COMPANY PROFILE V-001 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 01 COMPANY PROFILE 02 TEAM EXPERIENCE & PROJECT REFERENCES 03 PRODUCTS & SOLUTIONS USP AGENDA 04 VERTICAL SOLUTION EXAMPLE 05 Registered in USA, Video Network Security The VNS vision is to benefit from the pains of (VNS) aims to become a specialist video existing and new ITC and security systems surveillance technology provider with integrators and customers who are being forced bespoke CCTV for commercial, industrial, out of competition by more dominating government, banking, retail, hospitality, multinational & systems integrators who are not healthcare and transportation verticals in the quick to adopt emerging technology solutions E XEC UT IVE MENA region. and restricted to represents known brands. SUMMARY The MENA region has also been deprived of MENA regional security products sales is professional consultants for SMB’s who forecasted to exceed to $ 2.0 Billion in 2019 and strive to adapt technology innovations in the the commercialization of security in general, rapidly shifting market conditions both in the there is a substantial opportunity for VNS to face of inherently inflexible and established improve client’s ability to deliver innovative and installation methodologies, design criteria cost-effective security solutions that they and dinosaur technologies. otherwise are unable to access on their own. COMPANY LEGAL & BUSINESS STRUCTURE 1950 W. Corporate Way PMB 95972, Anaheim, California 92801, USA OWN CCTV BRAND STRATEGIC BRAND ALLIANCE & REPRESENTATION Server based Retail business intelligence -

Evergreen Aidilfitri

04 Aurora Series 20 PREMIUM CREATION 22 PUASA Series 24 COOKIES Series 26 Golden Series 30 Pyramid Series 34 Early Bird Special Evergreen Aidilfitri 35 Free Gift As we reflect on our wonderful blessings, we are very grateful for the amazing people who have filled our hearts with great comfort and joy. Like the warm wishes of Aidilfitri, may our bond be evergreen evermore. A most valuable gift isn’t always the most elaborate. It is the thought behind that gives your gift its lustre and brilliance. Give an evergreen gift that conveys your appreciation this auspicious season. -“Salam Aidilfitri”- CODE B01 | RM400 B02 • ELEGANT 6PCS GOLDEN EMBELLISHED TRAYS • WHITTARD RM Chelsea 1886 Tippy Assam Black Tea (United Kingdom) 50gm 150 • NESCAFE Gold Pure Soluble Arabica Coffee (Switzerland) 40gm • Bottlegreen Hand-Picked Elderflower Sparkling (United Kingdom) 750ml • East Coast Bakehouse Stem Ginger Chocolate Biscuits (Ireland) 160gm • Ital Classic Lingue Di Gatto Espresso Mocha B02 | RM150 Biscuits (Australia) 150gm • Hacizade Turkish Hazelnut Delight • GOLDEN RETRO ROUND PLATE • Valentino 250gm • Luxuries Dates Dhibs 230gm • Choc O’ Time Assortment Sparkling White Grape Drink 750ml • Amienah Milk Chocolate 100gm • Turkish Chocolate Dates 200gm Superior Hand Picked Lulu Dates (Iran) 250gm • ARMANEE Samosa Chicken Floss 120gm • ARMANEE Aurora • Citrahana Chocolate Cookies 80gm • Nutrigold Traditional Roasted Kacang Bandung 150gm • Citrahana Buttery Classic White Coffee 200gm • Premium Peanut Barley Cookies 180gm • Fine Recipe Traditional Kuih -

Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United

Richard V. Pouyat Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Toral Patel-Weynand Linda H. Geiser Editors Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions A Comprehensive Science Synthesis Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions Richard V. Pouyat • Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Toral Patel-Weynand • Linda H. Geiser Editors Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions A Comprehensive Science Synthesis Editors Richard V. Pouyat Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Northern Research Station Rocky Mountain Research Station USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service Newark, DE, USA Moscow, ID, USA Toral Patel-Weynand Linda H. Geiser Washington Office Washington Office USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service Washington, DC, USA Washington, DC, USA ISBN 978-3-030-45215-5 ISBN 978-3-030-45216-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45216-2 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 . This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.