In the Heat of the Moment: a Local Narrative of the Responses to a Fire in Lærdal, Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dkulturminne I HØYANGER

HISTORISK BAKGRUNN TIL LOKAL KULTURMINNEPLAN dKULTURMINNE I HØYANGER Høyanger kommune eld kraft vatn 2 Historiedel til lokal Kulturminneplan for Høyanger kommune FØREORD Kulturminna våre er viktige kunnskapsberarar som er med på å fortelje oss (pbl), samt utforme områdeplanlegging eller legge tematiske omsynssoner vår historie. Dei kan og vere identitetsberarar som fortel oss kven vi er og der ein ønskjer ei sikra utvikling m.o.t eigenart som arkitektur, bygningsmi - kvar vi kjem frå, og er med på å gi oss identitet og rotfeste. Dei viser utvik - ljø eller sentrumsstruktur. lingstrekk i vår historie, og kan fungere som eit kikhol inn i fortida. Fortidas kulturminne er med oss i notida og gir oss grunnlaget til å skape framtidas Den lokale kulturminneplan gir ikkje noko juridisk vern for kommunal og samfunn. eller privat eigedom. Men ved at Høyanger kommune vedtek den lokale kulturminneplanen vil dette kunne medføre auka midlar gjennom stønads - Kulturminneplanen skal vere eit verktøy i kulturminneforvaltninga. Den skal ordningar og tilgang på rettleiing i bruk og vedlikehald. 3 vere eit hjelpemiddel i ein strategi for å prioritere kulturminne. Ei anna vik - tig side er å kartlegge og formidle kunnskap om våre kulturminne. Dette er Høyanger kommune ønskjer ei god forvaltning av kulturminna i kommu - starten på ein prosess som på sikt vil gje god oversyn og kunnskap om nen. Difor må kulturminna settast inn i ein historisk samanheng. Utarbeida kulturminna i kommunen, både i forvaltninga og formidlinga av kultur - historisk bakgrunn er vedlegg til denne lokale kulturminneplan. minne. God lesing! Kulturminneplanen er i plansystemet til Høyanger kommune, underlagt kommuneplanen sin samfunnsdel, samt arealplanen der ein har bandlagt Arve Varden Anita Nordheim område etter kulturminnelova. -

E39 Lavik - Skei

Dovre Group ASS Transportøkonomisk institutt E39 Lavik - Skei Kvalitetssikring av konseptvalg (KS 1) Unntatt offentlighet, jf. § 5.2.b Hovedrapport Oppdragssgiver Samferdselsdepartementet Finansdepartementet Avgradert Dette dokumentet er avgradert av Samferdselsdepartementet og er ikke lenger unntatt offentlighet. Referanse: Brev fra Samferdselsdepartementet til Concept‐programmet 04.11.201 Ref: 09/380‐JRO KS 1 E39 Lavik - Skei FORORD I forbindelse med behandling av store statlige investeringer stilles det krav til ekstern kvalitetssikring ved avslutning av forstudiefasen (KS 1). KS 1 er en ekstern vurdering av Samferdselsdepartementets saksforberedelser forut for regjeringsbehandling, og en uavhengig anbefaling om hvilket konsept som bør videreføres i forprosjekt. Kvalitetssikringen er gjennomført i henhold til rammeavtale med Finansdepartementet av 10. juni 2005 om kvalitetssikring av konseptvalg, samt styringsunderlag og kostnadsoverslag for valgt prosjektalternativ. De viktigste konklusjoner og hovedresultater fra kvalitetssikringen av Lavik-Skei ble presentert for Statens vegvesen, Samferdselsdepartementet og Finansdepartementet 19. november 2008. Kommentarer gitt i møtet samt etterfølgende uttalelser fra Statens vegvesen er tatt hensyn til i rapporten. Dette dokumentet er hovedrapporten fra oppdraget. Vedlegg til hovedrapporten foreligger i eget dokument. Dovre International AS byttet navn til Dovre Group AS i oktober 2008. Oslo, 12. januar 2009 Stein Berntsen Administrerende direktør Joint Venture Dovre/TØI Dovre Group AS / TØI Side 3 av 33 Dato: 12.1.2009 KS 1 E39 Lavik - Skei SAMMENDRAG Utgangspunktet for kvalitetssikringen er et forslag om utbygging av E39 mellom Lavik og Skei. Strekningen er viktig for nord-sør-forbindelsen på vestlandet, lokaltrafikken i området og for trafikken til og fra regionsenteret Førde. Strekningen mellom Lavik og Skei er i følge Statens vegvesen preget av smal og svingete veg med delstrekninger som har dårlig bæreevne og lange parseller med nedsatt hastighet. -

Nordic Alcohol Policy in Europe: the Adaptation of Finland's, Sweden's and Norway's Alcohol

Thomas Karlsson Thomas Karlsson Thomas Karlsson Nordic Alcohol Policy Nordic Alcohol Policy in Europe in Europe The Adaptation of Finland’s, Sweden’s and Norway’s Alcohol Policies to a New Policy Framework, 1994–2013 The Adaptation of Finland’s, Sweden’s and Norway’s Alcohol Policies to a New Policy Framework, 1994–2013 Nordic Alcohol Policy in Europe Policy Alcohol Nordic To what extent have Finland, Sweden and Norway adapted their alcohol policies to the framework imposed on them by the European Union and the European Economic Area since the mid-1990s? How has alcohol policies in the Nordic countries evolved between 1994 and 2013 and how strict are their alcohol policies in comparison with the rest of Europe? These are some of the main research questions in this study. Besides alcohol policies, the analyses comprise the development of alcohol consumption and cross-border trade with alcohol. In addition to a qualitative analysis, a RESEARCH quantitative scale constructed to measure the strictness of alcohol policies is RESEARCH utilised. The results from the study clearly corroborate earlier findings on the significance of Europeanisation and the Single Market for the development of Nordic alcohol policy. All in all, alcohol policies in the Nordic countries are more liberal in 2013 than they were in 1994. The restrictive Nordic policy tradition has, however, still a solid evidence base and nothing prevents it from being the base for alcohol policy in the Nordic countries also in the future. National Institute for Health and Welfare P.O. -

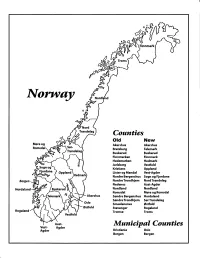

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Skaala Opp Trening 2003

Skaala Opp Trening 2003 Etternamn Fornamn Lag Stad Fødselsår Alsaker Janne Elin STRYN 1967 Andreassen Jan L. Terra Fonds OSLO 1964 Andreassen Stine Tertnes 1986 Andreassen Arne Tertnes IL TERTNES 1952 Andreassen Signe Tertnes IL TERTNES 1955 Angeltveit Arne ULVDAL 0 Arntsen Birthe Sandholm Geiranger idretslag GEIRANGER 1959 Auflem Egil Loen 1961 Aunaas Anne Lise SINTEF TRONDHEIM 1961 Austereim Anders 1955 Austreim Ove KYRKJEBØ 0 Bakke Terje Skanska BIL Bergen 1976 Bakke Unnvar OS 0 Bech Kristian Martin Nesttun 1956 Berger Rune Loen IL LOEN 1967 Berget Alf Kristian Stråheim IL ÅHEIM 1989 Bergset Anders Førde 1943 Bergsnes Rune HARAMSØY 1960 Bergsnes Ann-Karin EGGESBØNES 1964 Berstad Gunnar Stryn 1983 Berstad Vidar Elde HOLMEDAL 1958 Biehler Jean-Marc Paris 1965 Bippus Brunhilde Køningsfield 1964 Bjerknes Dag Ivar Volda 1963 Bjerknes Ragnhild Volda 1962 Bjerkvik Britt 0 Bjørset Annika Førde IL Førde 1990 Bjørstad Liv Marit Valldal IL VALLDAL 1956 Bjørsvik Arvid Viking Bergen 1943 Bjånesø Henry Bønes 0 Blindheim Britt J. Sula kommune LANGEVÅG 1955 Blomvik Per Magne EIDSNES 1955 Blomvik Eva Hilde EIDSNES 1955 Blaalid Bjørn Måløy Møløy 1953 Borren Anne Solfrid 1967 Breidablikk Marit Stryn 1974 Breidablikk Ole Petter ÅLESUND 1966 Breivik Lars Hasundgot IL ULSTEINVIK 1960 Breivik Marianne Hasundgot IL ULSTEINVIK 1965 Breivik Gerd Olden Røde Kors Hjelpekorps Utvik 1962 Brekke Kristin Isdalstø 1949 Brekken Olav Hydro BIL, Høyanger Vadheim 0 Brenna Susanne Ramstad NORDBERG 1951 Briksdal Frode Briksdal Breføring OLDEN 1966 Briksdal Hilde Briksdal Breføring OLDEN 1967 Brodshaug Jostein RPI VORMSUND 1949 Brunstad Nils Gunnar SYKKYLVEN 1958 Brunstad Kristin G Sykkylven 1960 Skaala Opp Trening 2003 Bruaas Lasse-Helge Lavik I.L. -

Høyanger 5 Walks 4

HØYANGER 5 WALKS 4 Høyanger. Foto Veri Media. 3 1 2 6 © VERI Media 13 7 8 Lavik. Foto Veri Media. 12 9 www.sognefjord.no Maps: www.ut.no 11 10 NACo, and it was the haunt for many single men. Here were buildings such as “Murgården” (“the Brick House”), “Slottet” (“the Castle”) and “Folkekjøkkenet” (“the People’s Kitchen”). Sæbøtangen was a mix of dwellings established by NACo, but also included private dwellings and businesses. This was a distinctive little quarter, and those who grew up in old Sæbøtangen tell of a lively local community. Some remained here all their lives, but for most it was a temporary solution. In the 1970s and 80s, most of old Sæbøtangen was demolished. 10 Parken (“the Park”) The area Parken was developed between 1916–1928 by NACo and was designed by architect Nicolai Beer. At the bottom of Kloumanns Allé is the Director’s House. He had all of his closest workers and the local management living in the surrounding houses. Throughout The Stairs. Foto Veri Media. the street there are wooden houses for workers, where up to four families could live in each house. The area is largely unchanged since then and is listed as a protected site. The Sogn and Fjordane Bustadbyggelag (“building co-operative”) has taken over all the Walking tour of Høyanger dwellings, with the exception of those facing the sea, which are still owned by the plant. Parken is currently a housing co-operative and employees of Hydro have priority in the Starting point Høyanger Town Square allocation of dwellings. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Folketeljing 1900 for 1415 Lavik Og Brekke Digitalarkivet

Folketeljing 1900 for 1415 Lavik og Brekke Digitalarkivet 26.09.2014 Utskrift frå Digitalarkivet, Arkivverket si teneste for publisering av kjelder på internett: http://digitalarkivet.no Digitalarkivet - Arkivverket Innhald Løpande liste .................................. 9 Førenamnsregister ........................ 75 Etternamnsregister ........................ 95 Fødestadregister .......................... 115 Bustadregister ............................. 147 4 Folketeljingar i Noreg Det er halde folketeljingar i Noreg i 1769, 1801, 1815, 1825, 1835, 1845, 1855, 1865, 1870 (i nokre byar), 1875, 1885 (i byane), 1891, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1946, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990 og 2001. Av teljingane før 1865 er berre ho frå 1801 nominativ, dvs. ho listar enkeltpersonar ved namn. Teljingane i 1769 og 1815-55 er numeriske, men med namnelistar i grunnlagsmateriale for nokre prestegjeld. Statistikklova i 1907 la sterke restriksjonar på bruken av nyare teljingar. Etter lov om offisiell statistikk og Statistisk Sentralbyrå (statistikklova) frå 1989 skal desse teljingane ikkje frigjevast før etter 100 år. 1910-teljinga blei difor frigjeven 1. desember 2010. Folketeljingane er avleverte til Arkivverket. Riksarkivet har originalane frå teljingane i 1769, 1801, 1815-1865, 1870, 1891, 1910, 1930, 1950, 1970 og 1980, mens statsarkiva har originalane til teljingane i 1875, 1885, 1900, 1920, 1946 og 1960 for sine distrikt. Folketeljinga 3. desember 1900 Ved kgl. res. 8. august 1900 blei det bestemt å halde ei "almindelig Folketælling" som skulle gje ei detaljert oversikt over befolkninga i Noreg natta mellom 2. og 3. desember 1900. På kvar bustad skulle alle personar til stades førast i teljingslista, med særskild markering ("mt") av dei som var mellombels til stades (på besøk osb.) på teljingstidspunktet. I tillegg skulle alle faste bebuarar som var fråverande (på reise, til sjøs osb.) frå bustaden på teljingstidspunktet, også førast i lista, men merkast som fråverande ("f"). -

Historia Om Hotellet I Lavik

Underetasje på 70-tallet Treskurd Johannes Hellebø 1995 ca. 1900 ca. 1900 Laurens Brock & Trijnie Cupido Lavik Fjord Hotell Historia om hotellet i Lavik Kjem du til Lavik sjøvegen, ser du straks ein større bygning ovanfor ekspressbåtkaien. Austlege delen av bygget er oppført i sveitserstil, noko som gjer at vi kan tidfeste den Per Sverre, 2000 Trijnie og Laurens, 2004 til slutten av 1800 talet. Mot vest er eit tilbygg av nyare dato. Slik ser Lavik Fjord Hotell ut i dag. Hotellet har gjennomgått fleire store endringar gjennom tida. 6947 Lavik - Norge Tlf. +47 57 71 40 40 [email protected] www.lavikfjordhotell.no Skrive av: Oddvar Løland Munnlege kjelder: Karl Hellebø, Anna og Leiv, 1948 20-tallet Per Sverre Kvammen og Laurens Brock Bilder: facebook/gamle lavik og Emmy M.V. af Geijerstam Johannes Hellebø bryllaup 1963 30-tallet Rom 201 på 70-tallet > 1864 I 1864 kom eit driftig ektepar (Peder Karlson Oppedal/Njøs og Gjertrud Ivers- dotter Oppedal) flyttande til Lavik etter å ha kjøpt ein del av Kvammen gard. Pe- ca. 1900 nye eigarane at skulle drifta kunne hal- kom på plass i første etasje og i kjellaren. der starta straks arbeidet med å få flytta de fram, måtte det til utviding og vidare I 2000 tok dei i bruk ny resepsjon og Fylkesbåtane sin båtstopp frå Værholm lensmann og sakførar. Desse hadde kon- av pensjonatet. Teikningar var ferdige i modernisering. Dei bygde til ein ny fløy bar. Ved side av resepsjonen vart innreia til Kvammen. Då stopp var sikra, blei det takatar som kom på vitjing. -

Skaala Opp Trening 2006

Skaala Opp Trening 2006 Etternamn Fornamn Lag Stad Fødselsår Agledal Grethe HYEN 1970 Almeland Kari MATHOPEN 1967 Almås Morten TERRA TRØKSTAD 1954 Almås Svanhild 1962 Alnes Henrik sykkylven il Sykkylven 1991 Alnes Martin G Sykkylven IL Sykkylven 1996 Alnes Severin Sykkylven IL Sykkylven 1996 Alnes Atle Sykkylven IL Sykkylven 1963 Andal Terje Naustdal 1963 Andal Venke Tambarskjelvar Naustdal 1962 Andersen Cathrine Bærum Skiklubb Haslum 1964 Andersen Arvid NORCONSULT Laksevåg 1961 Andersen Solfrid Leirvik i Sogn 1968 Andresen Randi Stadheim HELLESYLT 1947 Apalseth Per-Arne Ålesund 1965 Apalseth Roald Førde 1971 Apneseth Bjørn Tommy Coast Elite Raudeberg 1970 Atamanaku Karina Hjartdal 1986 Atna Leidulf 1947 Auflem Egil Loen 1961 Bakke Arvid Bergen 1954 Baldersheim Einar Knoff Balder Bergen 1966 Baldersheim Truls Håpet Bergen 1958 Barahona Juan Pinto Elko Bil Geithus 1952 Barstad Trond Ålesund 1965 Becker Thor Johan Nordre Sande Sande 1990 Bell Per Inge Gaular Sande 1958 Berg Kristian BUL OSLO 1994 Berg Petter BUL OSLO 1996 Bergesen Halvard Paul Bergen 1946 Bergesen Vivian Irene Brandt Bergen 1950 Bergset Terje Ålesund 1971 Bergset Anders Førde 1943 Bergseth Nancy Hødd ULSTEINVIK 1960 Berland Harald MATHOPEN 1956 Berntzen Nils Erik Mjøndalen 1944 Berntzen Karl-Erik Rykkinn 1971 Berstad Sigurd 1994 Berstad Vidar 1958 Berstad Gunnar Stryn 1983 Berstad Renate Stryn TIL 0 Berstad Espen Stryn TIL 0 Bertelsen Per LODDEFJORD 1957 Bigset Siv Bente Mork Hareid 1961 Binder Sturla FYKIL Leikanger 1971 Birkaas Inger Vadheim 1949 Bjerke Elin Rolls-Royce -

Reis Miljøvenleg Til Og Frå Høyanger!

Day excursions to Høyanger ACTIVITIES AND ATTRACTIONS: Høyangerbadet – The Høyanger pool – indoors and outdoors, Høyanger Industry museum, Hiking in the mountain, Fjord sightseeing tours to the Fjordside villages on the southside of Sognefjord. Hiking tours in Lavik. River walk, cultural trail and The «Stairs» in Høyanger, also in combination with hiking. DEPARTURE SKJOLDEN/LUSTER ALT BOAT TO FJORDSIDE VILLAGES Dep Skjolden 06.15 Fridays only, book in advance HØYANGER Dep Gaupne 06.55 Dep Høyanger 16.05 Dep Marifjøra 06.58 Arr Nordeide 16.15 Dep Hafslo 07.15 Dep Nordeide 16.15 Arr Sogndal 07.45 Arr Ortnevik 16.45 Dep Sogndal 08.55 Visit Ortnevik Arr Høyanger 11.00 Dep Ortnevik 17.35 Visit Høyanger Arr Vik 18.30 Dep Høyanger 12.15 14.55 Dep Vik 20.10 Arr Sogndal 14.20 16.50 Arr Sogndal 21.20 Dep Sogndal 15.30 17.10 Dep Sogndal 22.00 Arr Hafslo 15.50 17.35 Arr Fjærland 22.25 Arr Marifjøra 16.00 17.50 ALT BOAT TO FJORDSIDE VILLAGES Arr Gaupne 16.05 18.00 Tuesd and Thursd only, book in advance Arr Skjolden 18.35 Dep Høyanger 12.30 DEPARTURE BALESTRAND Arr Ortnevik 13.15 Dep Balestrand 10.10 Visit Ortnevik Arr Høyanger 11.00 Dep Ortnevik 16.45 Visit Høyanger Arr Nordeide 17.10 Dep Høyanger 12.15 16.00 Dep Nordeide 17.10 Arr Balestrand 13.05 16.40 Arr Balestrand 18.15 © Arvid Fimreite 65 DEPARTURE ØVRE ÅRDAL RECOMMENDED TOUR 3 Dep Ø Årdal 07.08 HIKING TIP Fjordside villages Dep Årdalstangen 07.25 Høyanger has many hiking Friday Arr Sogndal 08.35 trails to offer, such as Dep Høyanger 16.05 Dep Sogndal 08.55 Bergefjellet mountain (6 Arr Nordeide 16.15 Arr Høyanger 11.00 km, 2 hours walk) off from Dep Nordeide 16.15 Visit Høyanger the mountain road, a short Arr Ortnevik 16.45 Dep Høyanger 12.15 14.55 17.25 drive from Høyanger, eg by Visit Ortnevik Arr Sogndal 14.20 16.50 19.25 taxi. -

Styresak Fase 3

STYRESAK GÅR TIL: Styremedlemmer FØRETAK: Helse Førde HF DATO: 11.03.2020 SAKSHANDSAMAR: Arve Varden/ Vidar Vie SAKA GJELD: Prehospital plan - mandat for fase 3 og innføringsplan ARKIVSAK: 2020/1988 STYRET: MØTEDATO: STYRESAK: Styret i Helse Førde HF 23.03.2020 021/2020 FORSLAG TIL VEDTAK Styret godkjenner mandat for fase 3 for prehospitale tenester, og ber administrerande direktør orientere styret om framdrifta. Oppsummering Arbeidet med prehospital plan skal inn i fase 3 – implementering av vald modell, og mandatet for denne fasen skal vedtakast av styret i Helse Førde. Det står att viktig utgreiingsarbeid knytt til struktur. Notatet «Arbeidsform og førebels skisse til innføringsplan» skisserer korleis arbeidet i fase 3 skal gjennomførast. Fakta Styret i Helse Førde gjorde følgjande vedtak i sak 007/2020 24. januar: Styret er godt nøgd med prosessen og saksgrunnlaget som ligg føre. Plan for prehospitale tenester blir vedteken med desse presiseringane: 1. Endringane som gjeld døgnbilen i Lavik skal utgreiast vidare, og det skal vurderast alternative modellar. Kommunar, tilsetteorganisasjonar og verneteneste skal takast med i prosessen. Saka vert lagt fram for styret til endeleg avgjerd. 2. Administrerande direktør får i oppdrag å arbeide vidare med omgjering av døgnbil i Ytre Bremanger til einmannsbetent ambulanseressurs, alternativt redusere til ein ambulanse i Bremanger kommune. Kommunar, tilsetteorganisasjonar og verneteneste skal takast med i prosessen. Saka vert lagt fram for styret til endeleg avgjerd. 3. Det skal gjennomførast ein prøveperiode på tolv månader med flytting av dagbil frå Luster til Sogndal, slik det er omtala i sakstilfanget. Vedtak om endeleg flytting etter prøveperioden ligg til administrerande direktør. 4. Det blir gjennomført ei vurdering av kva for konsekvensar det vil ha for dei prehospitale tenestene at Hornindal kommune er slegen saman med Volda kommune og ikkje lenger er Helse Førde sitt ansvarsområde.