Frida Stångberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News from the CREW

Volume 6 • March 200 News from the CREW lthough 2009 has been a Asteraceae family) in full flower. REW, the Custodians of Areally challenging year with These plants are usually rather C Rare and Endangered the global recession having had inconspicuous and are very hard Wildflowers, is a programme a heavy impact on all of us, it to spot when not flowering, so that involves volunteers from we were very lucky to catch it could not break the strong spir- the public in the monitoring it of CREW. Amidst the great in flower. The CREW team has taken a special interest in the and conservation of South challenges we came up tops genus Marasmodes (we even Africa’s threatened plants. once again, with some excep- have a day in April dedicated to CREW aims to capacitate a tionally great discoveries. the monitoring of this genus) network of volunteers from as they all occur in the lowlands a range of socio-economic Our first great adventure for and are severely threatened. I backgrounds to monitor the year took place in the knew from the herbarium speci- and conserve South Afri- Villiersdorp area. We had to mens that there have not been ca’s threatened plant spe- collect flowering material of any collections of Marasmodes Prismatocarpus lycioides, a data cies. The programme links from the Villiersdorp area and volunteers with their local deficient species in the Campan- was therefore very excited conservation agencies and ulaceae family. We rediscovered about this discovery. As usual, this species in the area in 2008 my first reaction was: ‘It’s a particularly with local land and all we had to go on was a new species!’ but I soon so- stewardship initiatives to en- scrappy nonflowering branch. -

A Systematic Study of Berkheya and Allies (Compositae)

A systematic study of Berkheya and allies (Compositae) A thesis submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science of Rhodes University by Ntombifikile Phaliso April 2013 Supervisor: Prof. N.P. Barker (Botany Department, Rhodes University) Co-supervisor: Dr. Robert McKenzie (Botany Department, Rhodes University) Table of contents: Title ……………………………………………………………………………..I Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………...III Declaration……………………………………………………………………IV Abstract…………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 1: General Introduction……………………………………………..3 Chapter 2: The molecular phylogeny of Berkheya and allies……………...12 Aims………………………………………………………………………………………….12 2.1: Molecular (DNA-based) systematic……………………………………………………..12 2.2: Methods and Materials…………………………………………………………………..18 2.1.1: Sampling…………………………………………………………………………..18 2.1.2: DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing…………………………………..18 2.1.3: Sequence alignment……………………………………………………………..19 2.1.4: Phylogenetic Analyses …………………………………………………………...21 2.3: Results…………………………………………………………………………………..22 2.3.1: ITS data set………………………………………………………………………..22 2.3.2: psbA-trnH data set………………………………………………………………..23 2.3.3: Combined data set………………………………………………………………...24 2.4: Discussion……………………………………………………………………………….28 2.4.1: Phylogenetic relationships within the Berkheya clade……………………………28 2.4.2: Insights from the psbA-trnH & combined data set phylogenies………………….37 2.4.3: Taxonomic implications: paraphyly of Berkheya………………………………...39 2.4.4: Taxonomic Implications: Correspondence with -

Biodiversity and Ecology of Critically Endangered, Rûens Silcrete Renosterveld in the Buffeljagsrivier Area, Swellendam

Biodiversity and Ecology of Critically Endangered, Rûens Silcrete Renosterveld in the Buffeljagsrivier area, Swellendam by Johannes Philippus Groenewald Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Science in Conservation Ecology in the Faculty of AgriSciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Michael J. Samways Co-supervisor: Dr. Ruan Veldtman December 2014 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration I hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis, for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Ecology, is my own work that have not been previously published in full or in part at any other University. All work that are not my own, are acknowledge in the thesis. ___________________ Date: ____________ Groenewald J.P. Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Acknowledgements Firstly I want to thank my supervisor Prof. M. J. Samways for his guidance and patience through the years and my co-supervisor Dr. R. Veldtman for his help the past few years. This project would not have been possible without the help of Prof. H. Geertsema, who helped me with the identification of the Lepidoptera and other insect caught in the study area. Also want to thank Dr. K. Oberlander for the help with the identification of the Oxalis species found in the study area and Flora Cameron from CREW with the identification of some of the special plants growing in the area. I further express my gratitude to Dr. Odette Curtis from the Overberg Renosterveld Project, who helped with the identification of the rare species found in the study area as well as information about grazing and burning of Renosterveld. -

Garden Info Sheet Xeric Greatest Hits Plant As You Wish! Plant by Number Design Not Included

2017 garden in a box: Garden Info Sheet Xeric Greatest Hits Plant as you wish! Plant by number design not included. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 - Blanket Flower 4 - Hardy Orange Gazania 7 - Blue Grama Grass 2 - Red Daylily 5 - Blue Cap Sea Holly 3 - Oak-leaf Stonecrop 6 - Standing Ovation Little Bluestem Grass Blanket Flower Red Daylily Latin Name: Gaillardia aristata Latin Name: Hemerocallis ‘Red Select’ 1 Mature Height: 18- 24” 2 Mature Height: 30-36” Mature Spread: 18-24” Mature Spread: 24-30” Hardy To: 8,500’ Hardy To: 8,500’ Water: Low Water: Low Exposure: Full Sun Exposure: Sun Flower Color: Yellow, Bronze Flower Color: Dark Red Flower Season: Mid-Summer Flower Season: Early to Mid-Summer Attracts: Butterflies, Bees Attracts: Butterflies Description: A thick clump of fuzzy grayish-green leaves support Resistant To: Rabbits stems of large daisies consisting of half-domed, reddish-brown to Description: The Red Daylily features showy dark-red blossoms orange centers circled by ray florets of yellow or yellow/bronze bi- with vivid yellow throats. Hemerocallis is native to Asia, primarily color. The Blanket Flower is a Colorado native, and the entire plant eastern Asia, and adapts easily to many different climate zones. is covered with fuzzy hair. Daylilies have even been referred to as, the “perfect perennial”, due Care: The Blanket Flower appreciates a bit of pampering the first to their: brilliant color, drought tolerance, frost tolerance, adapt- season, and then takes off on its own. Be sure to deadhead occa- ability, hardiness, and low-maintenance nature. -

X-Ray Fluorescence Elemental Mapping of Roots, Stems and Leaves of the Nickel Hyperaccumulators Rinorea Cf

X-ray fluorescence elemental mapping of roots, stems and leaves of the nickel hyperaccumulators Rinorea cf. bengalensis and Rinorea cf. javanica (Violaceae) from Sabah (Malaysia), Borneo Antony van der Ent, Martin D. de Jonge & Rachel Mak & Jolanta Mesjasz-Przybyłowicz & Wojciech J. Przybyłowicz & Alban D. Barnabas & Hugh H. Harris Centre for Mined Land Rehabilitation, Sustainable Minerals Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia Australian Synchrotron, ANSTO, Melbourne, Australia School of Chemistry, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602, South Africa Faculty of Physics & Applied Computer Science, AGH University of Science and Technology, al. Mickiewicza 30, 30-059 Kraków, Poland Materials Research Department, iThemba LABS, National Research Foundation, P.O. Box 722, Somerset West 7129, South Africa Department of Chemistry, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia 1 ABSTRACT Aims There are major knowledge gaps in understanding the translocation leading from nickel uptake in the root to accumulation in other tissues in tropical nickel hyperaccumulator plant species. This study focuses on two species, Rinorea cf. bengalensis and Rinorea cf. javanica and aims to elucidate the similarities and differences in the distribution of nickel and physiologically relevant elements (potassium, calcium, manganese and zinc) in various organs and tissues. Methods High-resolution X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) of frozen-hydrated and fresh- hydrated tissue samples and nuclear microprobe (micro-PIXE) analysis of freeze-dried samples were used to provide insights into the in situ elemental distribution in these plant species. Results This study has shown that the distribution pattern of nickel hyperaccumulation is typified by very high levels of accumulation in the phloem bundles of roots and stems. -

Introduced Weed Species

coastline Garden Plants that are Known to Become Serious Coastal Weeds SOUTH AUSTRALIAN COAST PROTECTION BOARD No 34 September 2003 GARDEN PLANTS THAT HAVE BECOME Vegetation communities that originally had a diverse SERIOUS COASTAL WEEDS structure are transformed to a simplified state where Sadly, our beautiful coastal environment is under threat one or several weeds dominate. Weeds aggressively from plants that are escaping from gardens and compete with native species for resources such as becoming serious coastal weeds. Garden escapees sunlight, nutrients, space, water, and pollinators. The account for some of the most damaging environmental regeneration of native plants is inhibited once weeds are weeds in Australia. Weeds are a major environmental established, causing biodiversity to be reduced. problem facing our coastline, threatening biodiversity and the preservation of native flora and fauna. This Furthermore, native animals and insects are significantly edition of Coastline addresses a selection of common affected by the loss of indigenous plants which they rely garden plants that are having significant impacts on our on for food, breeding and shelter. They are also affected coastal bushland. by exotic animals that prosper in response to altered conditions. WHAT ARE WEEDS? Weeds are plants that grow where they are not wanted. Weeds require costly management programs and divert In bushland they out compete native plants that are then resources from other coastal issues. They can modify excluded from their habitat. Weeds are not always from the soil and significantly alter dune landscapes. overseas but also include native plants from other regions in Australia. HOW ARE WEEDS INTRODUCED AND SPREAD? WEEDS INVADE OUR COASTLINE… Weeds are introduced into the natural environment in a Unfortunately, introduced species form a significant variety of ways. -

Chorological Notes on the Non-Native Flora of the Province of Tarragona (Catalonia, Spain)

Butlletí de la Institució Catalana d’Història Natural, 83: 133-146. 2019 ISSN 2013-3987 (online edition): ISSN: 1133-6889 (print edition)133 GEA, FLORA ET fauna GEA, FLORA ET FAUNA Chorological notes on the non-native flora of the province of Tarragona (Catalonia, Spain) Filip Verloove*, Pere Aymerich**, Carlos Gómez-Bellver*** & Jordi López-Pujol**** * Meise Botanic Garden, Nieuwelaan 38, B-1860 Meise, Belgium. ** C/ Barcelona 29, 08600 Berga, Barcelona, Spain. *** Departament de Biologia Evolutiva, Ecologia i Ciències Ambientals. Secció Botànica i Micologia. Facultat de Biologia. Universitat de Barcelona. Avda. Diagonal, 643. 08028 Barcelona, Spain. **** Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB). Passeig del Migdia. 08038 Barcelona, Spain. Author for correspondence: F. Verloove. A/e: [email protected] Rebut: 10.07.2019; Acceptat: 16.07.2019; Publicat: 30.09.2019 Abstract Recent field work in the province of Tarragona (NE Spain, Catalonia) yielded several new records of non-native vascular plants. Cenchrus orientalis, Manihot grahamii, Melica chilensis and Panicum capillare subsp. hillmanii are probably reported for the first time from Spain, while Aloe ferox, Canna ×generalis, Cenchrus setaceus, Convolvulus farinosus, Ficus rubiginosa, Jarava plumosa, Koelreu- teria paniculata, Lycianthes rantonnetii, Nassella tenuissima, Paraserianthes lophantha, Plumbago auriculata, Podranea ricasoliana, Proboscidea louisianica, Sedum palmeri, Solanum bonariense, Tipuana tipu, Tradescantia pallida and Vitis ×ruggerii are reported for the first time from the province of Tarragona. Several of these are potential or genuine invasive species and/or agricultural weeds. Miscellane- ous additional records are presented for some further alien taxa with only few earlier records in the study area. Key words: Alien plants, Catalonia, chorology, Spain, Tarragona, vascular plants. -

Sand Mine Near Robertson, Western Cape Province

SAND MINE NEAR ROBERTSON, WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE BOTANICAL STUDY AND ASSESSMENT Version: 1.0 Date: 06 April 2020 Authors: Gerhard Botha & Dr. Jan -Hendrik Keet PROPOSED EXPANSION OF THE SAND MINE AREA ON PORTION4 OF THE FARM ZANDBERG FONTEIN 97, SOUTH OF ROBERTSON, WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE Report Title: Botanical Study and Assessment Authors: Mr. Gerhard Botha and Dr. Jan-Hendrik Keet Project Name: Proposed expansion of the sand mine area on Portion 4 of the far Zandberg Fontein 97 south of Robertson, Western Cape Province Status of report: Version 1.0 Date: 6th April 2020 Prepared for: Greenmined Environmental Postnet Suite 62, Private Bag X15 Somerset West 7129 Cell: 082 734 5113 Email: [email protected] Prepared by Nkurenkuru Ecology and Biodiversity 3 Jock Meiring Street Park West Bloemfontein 9301 Cell: 083 412 1705 Email: gabotha11@gmail com Suggested report citation Nkurenkuru Ecology and Biodiversity, 2020. Section 102 Application (Expansion of mining footprint) and Final Basic Assessment & Environmental Management Plan for the proposed expansion of the sand mine on Portion 4 of the Farm Zandberg Fontein 97, Western Cape Province. Botanical Study and Assessment Report. Unpublished report prepared by Nkurenkuru Ecology and Biodiversity for GreenMined Environmental. Version 1.0, 6 April 2020. Proposed expansion of the zandberg sand mine April 2020 botanical STUDY AND ASSESSMENT I. DECLARATION OF CONSULTANTS INDEPENDENCE » act/ed as the independent specialist in this application; » regard the information contained in this -

Berkheya – Bew(A)Ehrte Blütenwunder

✓⇠⌫⌧⇠⇡⌫⇠⌦⇤⇠ ⇥⌃↵⌅⌃⌅⌥⌥⌥✏⇣ ↵⇠⇢⇠ ⌦ Berkheya – bew(a)ehrte Blütenwunder SVEN NUERNBERGER Abstract The range of distribution of the genus Berkheya is centered in South Africa. Berkheya purpurea and B. multijuga reach high into the mountains of the Drakensberge and, accordingly, are adapted to cold and frost. With their conspicuous coloration and im- pressive large flower heads they are most suitable as ornamental herbaceous perennials. Zusammenfassung Südafrika ist das Hauptverbreitungsgebiet der Gattung Berkheya. Berkheya purpurea und B. multijuga dringen bis in die küh- len Gebirgsregionen der Drakensberge vor und verfügen daher über eine entsprechende Kälte- und Frosttoleranz. Ihre auffal- lend gefärbten Korbblüten von beachtlicher Größe machen sie für den Staudengarten interessant. 1. Einleitung Buschland (Fynbos) in tieferen Lagen. So kommt Neben den echten Disteln, die bekanntlich zu z. B. Berkheya zeyheri in Brachystegia-Wäldern den Korbblütlern gehören, gibt es viele distel- Mozambiques vor (HYDE & WURSTEN 2010). ähnliche Pflanzen, die zu verschiedenen anderen Die großen Zungenblüten einiger Arten sind in- Pflanzenfamilien zählen. Die hoch geschätzten tensiv gefärbt und lassen die engere Verwandt- Edeldisteln beispielsweise sind Doldenblütler schaft zu bekannten Zierpflanzen wie Gazania (Apiaceae) der Gattung Eryngium und die lang- und Arctotis erkennen. Innerhalb der Tribus blättrige Kardendistel (Morina longifolia) ist ein Arctotideae steht den Berkheyen die Gattung Geißblattgewächs (Caprifoliaceae). Innerhalb der Cullumia, deren Arten ebenfalls stachelig be- Korbblütler stehen auch die “African thistles“ wehrt sind, am nächsten (FUNK & CHAN 2008). der Gattung Berkheya. Sie sind mit Gazanien und Berkheya purpurea und B. multijuga sind vor Bärenohren (Arctotis) näher verwandt als mit den kurzem in das Blickfeld der Pflanzenproduzen- echten Disteln. Aufgrund ihres besonders attrak- ten gerückt. -

Vegetation Survey of Mount Gorongosa

VEGETATION SURVEY OF MOUNT GORONGOSA Tom Müller, Anthony Mapaura, Bart Wursten, Christopher Chapano, Petra Ballings & Robin Wild 2008 (published 2012) Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 23 VEGETATION SURVEY OF MOUNT GORONGOSA Tom Müller, Anthony Mapaura, Bart Wursten, Christopher Chapano, Petra Ballings & Robin Wild 2008 (published 2012) Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 23 Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P.O. Box FM730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe Vegetation Survey of Mt Gorongosa, page 2 SUMMARY Mount Gorongosa is a large inselberg almost 700 sq. km in extent in central Mozambique. With a vertical relief of between 900 and 1400 m above the surrounding plain, the highest point is at 1863 m. The mountain consists of a Lower Zone (mainly below 1100 m altitude) containing settlements and over which the natural vegetation cover has been strongly modified by people, and an Upper Zone in which much of the natural vegetation is still well preserved. Both zones are very important to the hydrology of surrounding areas. Immediately adjacent to the mountain lies Gorongosa National Park, one of Mozambique's main conservation areas. A key issue in recent years has been whether and how to incorporate the upper parts of Mount Gorongosa above 700 m altitude into the existing National Park, which is primarily lowland. [These areas were eventually incorporated into the National Park in 2010.] In recent years the unique biodiversity and scenic beauty of Mount Gorongosa have come under severe threat from the destruction of natural vegetation. This is particularly acute as regards moist evergreen forest, the loss of which has accelerated to alarming proportions. -

Albuca Spiralis

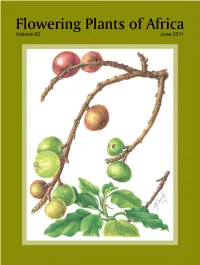

Flowering Plants of Africa A magazine containing colour plates with descriptions of flowering plants of Africa and neighbouring islands Edited by G. Germishuizen with assistance of E. du Plessis and G.S. Condy Volume 62 Pretoria 2011 Editorial Board A. Nicholas University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA D.A. Snijman South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA Referees and other co-workers on this volume H.J. Beentje, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK D. Bridson, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Burgoyne, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J.E. Burrows, Buffelskloof Nature Reserve & Herbarium, Lydenburg, RSA C.L. Craib, Bryanston, RSA G.D. Duncan, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA E. Figueiredo, Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA H.F. Glen, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Durban, RSA P. Goldblatt, Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis, Missouri, USA G. Goodman-Cron, School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, RSA D.J. Goyder, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK A. Grobler, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA R.R. Klopper, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J. Lavranos, Loulé, Portugal S. Liede-Schumann, Department of Plant Systematics, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany J.C. Manning, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA A. Nicholas, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA R.B. Nordenstam, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden B.D. Schrire, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Silveira, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal H. Steyn, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA P. Tilney, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, RSA E.J. -

Genetic Diversity and Evolution in Lactuca L. (Asteraceae)

Genetic diversity and evolution in Lactuca L. (Asteraceae) from phylogeny to molecular breeding Zhen Wei Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr M.E. Schranz Professor of Biosystematics Wageningen University Other members Prof. Dr P.C. Struik, Wageningen University Dr N. Kilian, Free University of Berlin, Germany Dr R. van Treuren, Wageningen University Dr M.J.W. Jeuken, Wageningen University This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School of Experimental Plant Sciences. Genetic diversity and evolution in Lactuca L. (Asteraceae) from phylogeny to molecular breeding Zhen Wei Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr A.P.J. Mol, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Monday 25 January 2016 at 1.30 p.m. in the Aula. Zhen Wei Genetic diversity and evolution in Lactuca L. (Asteraceae) - from phylogeny to molecular breeding, 210 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2016) With references, with summary in Dutch and English ISBN 978-94-6257-614-8 Contents Chapter 1 General introduction 7 Chapter 2 Phylogenetic relationships within Lactuca L. (Asteraceae), including African species, based on chloroplast DNA sequence comparisons* 31 Chapter 3 Phylogenetic analysis of Lactuca L. and closely related genera (Asteraceae), using complete chloroplast genomes and nuclear rDNA sequences 99 Chapter 4 A mixed model QTL analysis for salt tolerance in