Nonsense and Trauma in the Works of Mervyn Peake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

Examining the Relationship Between Children's

A Spoonful of Silly: Examining the Relationship Between Children’s Nonsense Verse and Critical Literacy by Bonnie Tulloch B.A., (Hons), Simon Fraser University, 2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Children’s Literature) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2015 © Bonnie Tulloch, 2015 Abstract This thesis interrogates the common assumption that nonsense literature makes “no sense.” Building off research in the fields of English and Education that suggests the intellectual value of literary nonsense, this study explores the nonsense verse of several North American children’s poets to determine if and how their play with language disrupts the colonizing agenda of children’s literature. Adopting the critical lenses of Translation Theory and Postcolonial Theory in its discussion of Dr. Seuss’s On Beyond Zebra! (1955) and I Can Read with My Eyes Shut! (1978), along with selected poems from Shel Silverstein’s Where the Sidewalk Ends (1974), A Light in the Attic (1981), Runny Babbit (2005), Dennis Lee’s Alligator Pie (1974), Nicholas Knock and Other People (1974), and JonArno Lawson’s Black Stars in a White Night Sky (2006) and Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box (2012), this thesis examines how the foreignizing effect of nonsense verse exposes the hidden adult presence within children’s literature, reminding children that childhood is essentially an adult concept—a subjective interpretation (i.e., translation) of their lived experiences. Analyzing the way these poets’ nonsense verse deviates from cultural norms and exposes the hidden adult presence within children’s literature, this research considers the way their poetry assumes a knowledgeable implied reader, one who is capable of critically engaging with the text. -

The Last Station

Mongrel Media Presents The Last Station A Film by Michael Hoffman (112 min, Germany, Russia, UK, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html THE LAST STATION STARRING HELEN MIRREN CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER PAUL GIAMATTI ANNE-MARIE DUFF KERRY CONDON and JAMES MCAVOY WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY MICHAEL HOFFMAN PRODUCED BY CHRIS CURLING JENS MEURER BONNIE ARNOLD *Official Selection: 2009 Telluride Film Festival SYNOPSIS After almost fifty years of marriage, the Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren), Leo Tolstoy’s (Christopher Plummer) devoted wife, passionate lover, muse and secretary—she’s copied out War and Peace six times…by hand!—suddenly finds her entire world turned upside down. In the name of his newly created religion, the great Russian novelist has renounced his noble title, his property and even his family in favor of poverty, vegetarianism and even celibacy. After she’s born him thirteen children! When Sofya then discovers that Tolstoy’s trusted disciple, Chertkov (Paul Giamatti)—whom she despises—may have secretly convinced her husband to sign a new will, leaving the rights to his iconic novels to the Russian people rather than his very own family, she is consumed by righteous outrage. This is the last straw. Using every bit of cunning, every trick of seduction in her considerable arsenal, she fights fiercely for what she believes is rightfully hers. -

01 to 06 MAY Terry Waite

Mark Billingham Ross Collins Kerry Brown Maura Dooley Matt Haig Darren Henley Emma Healey Patrick Gale Guernsey Literary Erin Kelly Huw Lewis-Jones Adam Kay Kiran Millwood Hargrave Kiran FestivalLibby Purves 2019 Lionel Shriver Philip Norman Philip 01 TO 06 MAY Terry Waite Terry Chrissie Wellington Piers Torday Lucy Siegle Lemn Sissay MBE Jessica Hepworth Benjamin Zephaniah ANA LEAF FOUNDATION MOONPIG APPLEBY OSA RECRUITMENT BROWNS ADVOCATES PRAXISIFM BUTTERFIELD RANDALLS DOREY FINANCIAL MODELLING RAWLINSON & HUNTER GUERNSEY ARTS COMMISSION ROTHSCHILD & CO GUERNSEY POST SPECSAVERS JULIUS BAER THE FORT GROUP Sophy Henn Kindly sponsored by sponsored Kindly THE INTERNATIONAL STOCK EXCHANGE THE GUERNSEY SOCIETY Turning the Tide on Plastic: How St James: £10/£5 Lucy Siegle Humanity (And You) Can Make Our Welcome to the Globe Clean Again seventh Guernsey Presenter on BBC’s The One Show and columnist for the Observer and the Guardian, Lucy Siegle offers a unique and beguiling perspective on environmental issues and ethical consumerism. Turning the Tide on Literary Festival Plastic provides a powerful call to arms to end the plastic pandemic along with the tools we need to make decisive change. It is a clear- eyed, authoritative and accessible guide to help us to take decisive and 13:00 to 14:00 effective personal action. Thursday 2 May Message from Sponsored by PraxisIFM Message from Claire Allen, Terry Waite CBE OGH Hotel: £25 Festival Director This is Going to Hurt Business Breakfast As Honorary I am very proud to welcome Professor Kerry you to the seventh Guernsey Chairman of the Literary Festival! With over Adam Kay Thursday 2 May Brown: The World Guernsey Literary 19:30 to 20:30 60 events for all interests According to Xi Festival it is once and ages, the festival is a Kerry Brown is Professor of again my pleasure unique opportunity to be inspired by writers. -

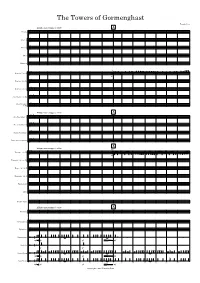

The-Towers-Of-Gormenghast-Web.Pdf

The Towers of Gormenghast Timothy Rees Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Piccolo ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 1 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 2 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Oboe & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bassoon ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Tpt. j j j j j œ œ Clarinet 1 in Bb ° # 6 Œ™ Œ j œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ & # 8 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ œ œ œ œ ∑ mf ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 2 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Clarinet in Eb # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bass Clarinet # in Bb # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Alto Saxophone 1 ° # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Saxophone 2 # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tenor Saxophone # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Baritone Saxophone # # # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 A Allegro non troppo q . = 108 solo Trumpet 1 in Bb ° # j j œ œ œ j œ œ œ œ & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Œ™ Œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ mfœ œ J J J œ J J Trumpet 2 & 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Horn 1 & 2 in F # & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Trombone 1 & 2 ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Euphonium ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tuba ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Double Bass ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Timpani °? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Glockenspiel ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ -

BECKY SHRIMPTON 416.300.8237 – [email protected]

BECKY SHRIMPTON 416.300.8237 – [email protected] - www.beckyshrimpton.com Agent – Paul Smith - ETM HEIGHT: 5’5’’ WEIGHT: 140 lbs HAIR: Dark Brown EYES: Green SELECTED FILM & TELEVISION Stress Vaccine Lead Tom Mae/Tom Mae Productions Be Alert Bert – Martial Arts Lead Lisa Lovatt/ITV Be Alert Bert – Shoplifting Lead James Martins/ITV The Ghost is a Lie Lead Jason Armstrong/Skeleton Key Global Surviving Evil – Season 2 Episode 4 Principal Emily/Schooley/Laughing Cat Productions Giving You the Business Season 1 Episode 8 Principal Joel Goldberg/FoodNetwork USA Canada! Principal Cameron Maitland/Farmervision Irresistible Force Principal Cameron Maitland/Farmervision Mask-a-raid Principal Liza Callahan/VFS Productions Cutaway Principal Kazik Radwanski/MDFF Films The Missing Me Principal Attila Kallai/Atka Films The Drinking Helps Principal Josh Kingston/Mom's Proud Productions Tower Principal Kazik Radwanski/MDFF Films Inspiration Actor Jason Armstrong/Skeleton Key Global Films Strange Famous Music Video Actor Dustin Kuypers/The Documentarians Motives and Murders Season 5 Episode 6 Actor Cineflix Productions SELECTED ANIMATION VOICE OVER Fireman Sam Helen Flood Susan Hart/Kitchen Sync Mage and Minions Female Heroes John Welch/Making Fun Inc. Doki Multiple Characters Susan Hart/Investigation Kids Brambleberry Tales Narrator David Lam/Rival Schools Firefall Nina Ian Macmillan/VFS Productions HellBent Beatrix Samantha Satiago/Ringling Animations DecorView Kate Chad Parker/FunnelBox Media Ring Run Circus Nina Sebastian Fernandez/Kalio Productions -

1.Hum-Roald Dahl's Nonsense Poetry-Snigdha Nagar

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(P): 2347-4564; ISSN(E): 2321-8878 Vol. 4, Issue 4, Apr 2016, 1-8 © Impact Journals ROALD DAHL’ S NONSENSE POETRY: A METHOD IN MADNESS SNIGDHA NAGAR Research Scholar, EFL University, Tarnaka, Hyderabad, India ABSTRACT Following on the footsteps of writers like Louis Carroll, Edward Lear, and Dr. Seuss, Roald Dahl’s nonsensical verses create a realm of semiotic confusion which negates formal diction and meaning. This temporary reshuffling of reality actually affirms that which it negates. In other words, as long as it is transitory the ‘nonsense’ serves to establish more firmly the authority of the ‘sense.’ My paper attempts to locate Roald Dahl’s verse in the field of literary nonsense in as much as it avows that which it appears to parody. Set at the brink of modernism these poems are a playful inditement of Victorian conventionality. The three collections of verses Rhyme Stew, Dirty Beasts, and Revolving Rhyme subvert social paradigms through their treatment of censorship and female sexuality. Meant primarily for children, these verses raise a series of uncomfortable questions by alienating the readers with what was once familiar territory. KEYWORDS : Roald Dahl’s Poetry, Subversion, Alienation, Meaning, Nonsense INTRODUCTION The epistemological uncertainty that manifested itself during the Victorian mechanization reached its zenith after the two world wars. “Even signs must burn.” says Jean Baudrillard in For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (1981).The metaphor of chaos was literalized in works of fantasy and humor in all genres. -

Humour in Nonsense Literature

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2017.5.3.holobut European Journal of Humour Research 5 (3) 1–3 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Editorial: Humour in nonsense literature Agata Hołobut Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland [email protected] Władysław Chłopicki Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland [email protected] The present special issue is quite unique. It grew out of a one-off scholarly seminar entitled BLÖÖF: Nonsense in Translation and Beyond, which attracted international scholars to the Institute of English Studies of Kraków’s Jagiellonian University on 18 May 2016 – a venue which had earlier yielded the series of studies entitled In Search of (Non)Sense (Chrzanowska- Kluczewska & Szpila 2009). The discussion at the seminar brought everyone to the, perhaps inevitable, conclusion that nonsense is bound to be humorous, and thus nonsense is definitely within the scope of humour studies. “Nonsense expressions easily become humorous ones, as humans often obtain pleasure from linguistic play and are ready to look for alternative paths to produce meaning. Nonsense has been experienced as a form of freedom, especially as a means to free thinking from the conventional bindings of logic and language” (Viana 2014). The interest in literary nonsense is quite long dating back to such grand figures as Dante, Rabelais, Erasmus of Rotterdam, and especially notably to the Anglosphere with its grand figures of Jonathan Swift, Lawrence Sterne, Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, James Joyce, and Samuel Beckett. At least since the time of Lewis Carroll and the antics of Alice in Wonderland nonsense humour rose to the status of a ‘typically English’ phenomenon, and the subject of creative nonsense or sense in nonsense has been quite prominent in English-language literary studies, whether of verse or prose. -

Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone Ebook Free Download

THE GORMENGHAST NOVELS: TITUS GROAN / GORMENGHAST / TITUS ALONE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mervyn Laurence Peake | 1168 pages | 01 Dec 1995 | Overlook Press | 9780879516284 | English | New York, United States The Gormenghast Novels: Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone PDF Book Tolkien, but his surreal fiction was influenced by his early love for Charles Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson rather than Tolkien's studies of mythology and philology. It was very difficult to get through or enjoy this book, because it feels so very scattered. But his eyes were disappointing. Nannie Slagg: An ancient dwarf who serves as the nurse for infant Titus and Fuchsia before him. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. I honestly can't decide if I liked it better than the first two or not. So again, mixed feelings. There is no swarmer like the nimble flame; and all is over. How does this vast castle pay for itself? The emphasis on bizarre characters, or their odd characteristics, is Dickensian. As David Louis Edelman notes, the prescient Steerpike never seems to be able to accomplish much either, except to drive Titus' father mad by burning his library. At the beginning of the novel, two agents of change are introduced into the stagnant society of Gormenghast. However, it is difficult for me to imagine how such readers could at once praise Peake for the the singular, spectacular world of the first two books, and then become upset when he continues to expand his vision. Without Gormenghast's walls to hold them together, they tumble apart in their separate directions, and the narrative is a jumbled climb around a pile of disparate ruins. -

TLG to Big Reading

The Little Guide to Big Reading Talking BBC Big Read books with family, friends and colleagues Contents Introduction page 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group page 4 Book groups at work page 7 Some ideas on what to talk about in your group page 9 The Top 21 page 10 The Top 100 page 20 Other ways to share BBC Big Read books page 26 What next? page 27 The Little Guide to Big Reading was created in collaboration with Booktrust 2 Introduction “I’ve voted for my best-loved book – what do I do now?” The BBC Big Read started with an open invitation for everyone to nominate a favourite book resulting in a list of the nation’s Top 100 books.It will finish by focusing on just 21 novels which matter to millions and give you the chance to vote for your favourite and decide the title of the nation’s best-loved book. This guide provides some ideas on ways to approach The Big Read and advice on: • setting up a Big Read book group • what to talk about and how to structure your meetings • finding other ways to share Big Read books Whether you’re reading by yourself or planning to start a reading group, you can plan your reading around The BBC Big Read and join the nation’s biggest ever book club! 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group “Ours is a social group, really. I sometimes think the book’s just an extra excuse for us to get together once a month.” “I’ve learnt such a lot about literature from the people there.And I’ve read books I’d never have chosen for myself – a real consciousness raiser.” “I’m reading all the time now – and I’m not a reader.” Book groups can be very enjoyable and stimulating.There are tens of thousands of them in existence in the UK and each one is different. -

1 Introduction: the Urban Gothic of the British Home Front

Notes 1 Introduction: The Urban Gothic of the British Home Front 1. The closest material consists of articles about Elizabeth Bowen, but even in her case, the wartime work has been relatively under-explored in terms of the Gothic tradition. Julia Briggs mentions Bowen’s wartime writing briefly in her article on “The Ghost Story” (130) and Bowen’s pre-war ghost stories have been examined as Gothic, particularly her short story “The Shadowy Third”: see David Punter (“Hungry Ghosts”) and Diana Wallace (“Uncanny Stories”). Bowen was Anglo-Irish, and as such has a complex relationship to national identity; this dimension of her work has been explored through a Gothic lens in articles by Nicholas Royle and Julian Moynahan. 2. Cultural geography differentiates between “place” and “space.” Humanist geographers like Yi-Fu Tuan associate place with security and space with free- dom and threat (Cresswell 8) but the binary of space and place falls into the same traps as all binaries: one pole tends to be valorised and liminal positions between the two are effaced. I use “space” because I distrust the nostalgia that has often accreted around “place,” and because – as my discussion of post- imperial geographies will show – even clearly demarcated places are sites of incorrigibly intersecting mobilities (Chapter 2). In this I follow the cultural geographers who contend that place is constituted by reiterative practice (Thrift; Pred) and is open and hybrid (Massey). 3. George Chesney’s The Battle of Dorking: Reminiscences of a Volunteer (1871) was one of the earliest of these invasion fictions, and as the century advanced a large market for the genre emerged William Le Queux was the most prolific writer in the genre, his most famous book being The Invasion of 1910, With a Full Account of the Siege of London (1906). -

The Pubs of Fitzrovia by Stephen Holden in a Dance to the Music of Time Powell Possibly Others Too

The Anthony Powell Society Newsletter Issue 44, Autumn 2011 ISSN 1743-0976 Annual AP Lecture The Politics of the Dance Prof. Vernon Bogdanor Friday 18 November AGM – Saturday 22 October London AP Birthday Lunch Saturday 3 December Secretary’s New Year Breakfast Saturday 14 January 2012 Borage & Hellebore with Nick Birns Saturday 17 March 2012 See pages 12-15 Full event details pages 16-17 Contents From the Secretary’s Desk … 2 Character or Situation? … 3-4 Fitzrovia Pubs … 5-8 2011 Literary Anniversaries … 9-11 REVIEW: Caledonia … 13 Scotchmen in a Brouhaha … 14-15 Society Notices … 12, 18, 19 Dates for Your Diary … 16-17 The Crackerjacks … 20-21 Local Group News … 22 From the APLIST … 23-25 Cuttings … 26-28 Letters to the Editor … 29 Merchandise & Membership … 30-32 Anthony Powell Society Newsletter #44 From the Secretary’s Desk The Anthony Powell Society Registered Charity No. 1096873 “Everything is buzz-buzz now”! The Anthony Powell Society is a charitable Somehow everything in the world of AP literary society devoted to the life and works and the Society is buzzing. It’s all of the English author Anthony Dymoke coming together. We have an event in Powell, 1905-2000. London in every month from now until the Spring Equinox. Officers & Executive Committee Patron: John MA Powell By the time you read this the conference will be upon us – perhaps even past. President: Simon Russell Beale, CBE What a great event that promises to be. Hon. Vice-Presidents: We have an excellent selection of Julian Allason speakers and papers; and some Patric Dickinson, LVO interesting events lined up.