2018 Oliver S Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

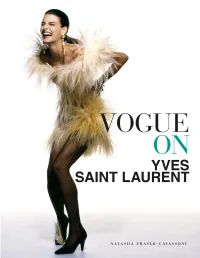

Vogue on Yves Saint Laurent

Model Carrie Nygren in Rive Gauche’s black double-breasted jacket and mid-calf skirt with long- sleeved white blouse; styled by Grace Coddington, photographed by Guy Bourdin, 1975. Linda Evangelista wears an ostrich-feathered couture slip dress inspired by Saint Laurent’s favourite dancer, Zizi Jeanmaire. Photograph by Patrick Demarchelier, 1987. At home in Marrakech, Yves Saint Laurent models his new ready-to-wear line, Rive Gauche Pour Homme. Photograph by Patrick Lichfield, 1969. DIOR’S DAUPHIN FASHION’S NEW GENIUS A STYLE REVOLUTION THE HOUSE THAT YVES AND PIERRE BUILT A GIANT OF COUTURE Index of Searchable Terms References Picture credits Acknowledgments “CHRISTIAN DIOR TAUGHT ME THE ESSENTIAL NOBILITY OF A COUTURIER’S CRAFT.” YVES SAINT LAURENT DIOR’S DAUPHIN n fashion history, Yves Saint Laurent remains the most influential I designer of the latter half of the twentieth century. Not only did he modernize women’s closets—most importantly introducing pants as essentials—but his extraordinary eye and technique allowed every shape and size to wear his clothes. “My job is to work for women,” he said. “Not only mannequins, beautiful women, or rich women. But all women.” True, he dressed the swans, as Truman Capote called the rarefied group of glamorous socialites such as Marella Agnelli and Nan Kempner, and the stars, such as Lauren Bacall and Catherine Deneuve, but he also gave tremendous happiness to his unknown clients across the world. Whatever the occasion, there was always a sense of being able to “count on Yves.” It was small wonder that British Vogue often called him “The Saint” because in his 40-year career women felt protected and almost blessed wearing his designs. -

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism National Gallery of Art Teacher Institute 2014

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism National Gallery of Art Teacher Institute 2014 Painters of Modern Life in the City Of Light: Manet and the Impressionists Elizabeth Tebow Haussmann and the Second Empire’s New City Edouard Manet, Concert in the Tuilleries, 1862, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London Edouard Manet, The Railway, 1873, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art Photographs of Baron Haussmann and Napoleon III a)Napoleon Receives Rulers and Illustrious Visitors To the Exposition Universelle, 1867, b)Poster for the Exposition Universelle Félix Thorigny, Paris Improvements (3 prints of drawings), ca. 1867 Place de l’Etoile and the Champs-Elysées Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, 1873, oil on canvas, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Great Boulevards, 1875, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Pont Neuf, 1872, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Collection Hippolyte Jouvin, The Pont Neuf, Paris, 1860-65, albumen stereograph Gustave Caillebotte, a) Paris: A Rainy Day, 1877, oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago, b) Un Balcon, 1880, Musée D’Orsay, Paris Edouard Manet, Le Balcon, 1868-69, oil on canvas, Musée D’Orsay, Paris Edouard Manet, The World’s Fair of 1867, 1867, oil on canvas, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo (insert: Daumier, Nadar in a Hot Air Balloon, 1863, lithograph) Baudelaire, Zola, Manet and the Modern Outlook a) Nadar, Charles Baudelaire, 1855, b) Contantin Guys, Two Grisettes, pen and brown ink, graphite and watercolor, Metropolitan -

^ 1934 Rae and Raymond

THE GLENGARRY NEWS ALBXAJSTDRIA, ONT, FRIDAY. DECEMBER 22, 1933. VOL. XLI-4^0. 52. $2.00 A YEAR Sbgarry’s Second Rev. A. L FAcDonalil Onlario's legislature Te Peace On Earth Mr. Jes. J. Aeeneilf Corewall Hauers Aeges 1. Mclaughlin Celebrates His Silver Jubilee Open January 31$t For a short space 'Of time the whirl- Feriuer Gteegarrian Passes . Annual Seed Fair ^ ing storm of words is hush^ and we Sir Arllrer Currie Hies AI livingsten, Meet. As annoTiiieed previously the Glen- On Thursday morning of last week. ^ Toronto, December 19.— The fifth speak the sentences which convey the Joseph J. Kennedy, resident of Ash- In common with eVery city and town (The Livingston Enterprise, Dec 6) garry Plowmen ^8 Association are tin- Dee. I4th,. Rev. Alexander L. McDon- an(j last session of the 18th Legis- kindly sent'ments of the season asso- land,, Wisconsin for over 40 years and ' in Canada where a branch of the Angus Ii. McLaughlin, pioneer con- dertaking once again the task of put- ald, P.P. o!£l Sft, Mary's, WilUaras- lature of Ontario will open January ciated with^ the coming of the Prince a member of the Chequamegon Bay Canadian Legion of the B.E.S.L. is tiaetor of Park county^ was called by ting on a “Seed Pair”. This Exhibi- town and St. William’s Chapel Mar- 31 Premier George S. Henry announc- of Peace. Few years have heard so. Old Settlers’ Club passed away Sun located members of the Canadian Le- death at his - home on West Geyser tion will be held at Alexandria, on the tintown,observed the silver jubilee of ed today'following decision of the Cab- many words uttered, about the past day, October at the home of his gion ofl Cornwall held a memorial ser- street, Tuesday afternoon 5th inst, 17th and 18th of January. -

The Pirates and Pop Music Radio

SELLING THE SIXTIES Was pirate radio in the sixties a non-stop psychedelic party – an offshore discothèque that never closed? Or was there more to it than hip radicalism and floating jukeboxes? From the mavericks in the Kings Road and the clubs ofSohotothemultinationaladvertisers andbigbusiness boardrooms Selling the Sixties examines the boom of pirate broadcasting in Britain. Using two contrasting models of unauthorized broadcasting, Radios Caroline and London, Robert Chapman situates offshore radio in its social and political context. In doing so, he challenges many of the myths which have grown up around the phenomenon. The pirates’ own story is framed within an examination of commercial precedents in Europe and America, the BBC’s initial reluctance to embrace pop culture, and the Corporation’s eventual assimilation of pirate programming into its own pop service, Radio One. Selling the Sixties utilizes previously unseen evidence from the pirates’ own archives, revealing interviews with those directly involved, and rare audio material from the period. This fascinating look at the relationship between unauthorized broadcasting and the growth of pop culture will appeal not only to students of communications, mass media, and cultural studies but to all those with an enthusiasm for radio history, pop, and the sixties. Robert Chapman’s broadcasting experience includes BBC local radio in Bristol and Northampton. He has also contributed archive material to Radios One and Four. He is currently Lecturer and Researcher in the Department of Performing Arts and Media Studies at Salford College of Technology. Selling the Sixties THE PIRATES AND POP MUSIC RADIO ROBERT CHAPMAN London and New York First published 1992 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge a division of Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc. -

Long Branch Daily Record. Vol

LONG BRANCH DAILY RECORD. VOL. 11-NUMBER 130 LONG BRANCH, N. J., TUESDAY, JUNE 4, 1912. 12 PAGES PRICE TWO CENTS WILSON STOCK HAS RED BANK VICTIM LITTLE MONEY SPENT C0NSEH1F PAPERS OF FIREWORKS BOMB BY CANDIDATES IN Victory In New Jersey Last Eldest Son of Broadway Un- Queries Are Received As To Week Greatest of Three MAY BE DEPORTED dertaker, Long III, Succumbs LAST PRIMARIES Whether Backward Step Notable Ones. to Attack of Heart Trouble. Is Contemplated. Trenton, June 4.—Governor Wood- Former Strike Breaker Who Had One Arm Blown John Edgar Morris, *ldeat son or Colby Contributed Highest Amount, $2,500. And Uelow are- printed three letters re- row Wilson Presidential stock ad- Coroner and Mrs. William II. Morris, cently received Inquiring ua to wheth- er Uing Branch cau be contemplating vanced many points last week and his Jr., died suddenly at. the home of his 1 New Jersey managers say now that Off And Other Paralyzed Will Probably Be parents, with whom lie resided, Broad- Contributions Ranged Down To 80 Cents- Het- stopping doing its part to 'boost its ad- he cannot be beaten for the nomna- way, this city, at 7 o'clock last night. vantages and attract people" and cap- tion. The Governor's overwhelming Sent Back To Russia With His Fam- Edgar, ua the young man was best rick Credited With $24.20-Scheimar's Fund itut here, and upeakiug highly of the victory in this State laBt Tuesday, known, had not been in the best of ^Tective work that has been done in liia winning the Minnesota delegates health for some time past, and after ho past by the Publicity Bureau: and his carrying the Texas State con- t ily By Borough being around the Morns' funeral par- $450.00--Wilson's Monmouth Vote The Evening POBI, publication office, vention, the three victories giving lors Sunday morning, he retired to bis 20 Veaey street, New York City. -

UNSTITCHING the 1950S FILM Á COSTUMES: HIDDEN

1 UNSTITCHING THE 1950s FILM Á COSTUMES: HIDDEN DESIGNERS, HIDDEN MEANINGS Volume I of II Submitted by Jennie Cousins, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film Studies, October 2008. This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. …………………………………. 2 Abstract This thesis showcases the work of four costume designers working within the genre of costume drama during the 1950s in France, namely Georges Annenkov, Rosine Delamare, Marcel Escoffier, and Antoine Mayo. In unstitching the cinematic wardrobes of these four designers, the ideological impact of the costumes that underpin this prolific yet undervalued genre are explored. Each designer’s costume is undressed through the identification of and subsequent methodological focus on their signature garment and/or design trademark. Thus the sartorial and cinematic significance of the corset, the crinoline, and accessories, is explored in order to determine an ideological pattern (based in each costumier’s individual design methodology) from which the fabric of this thesis may then be cut. In so doing, the way in which film costume speaks as an independent producer of cinematic meaning may then be uncovered. By viewing costume design as an autonomous ideological system, rather than a part of mise-en- scène subordinate to narrative, this fabric-centric enquiry consolidates Stella Bruzzi’s insightful exploration of film costume in Undressing Cinema, Clothing and Identity in the Movies (1997). -

The Glengarry News CIRCULATIONS the Fineshp, WEEKLY NEWSPAPER in EASTERN ONTARIO

V, V /MEMBERV ^UDIT \ BUREAU > The Glengarry News CIRCULATIONS THE FINEShp, WEEKLY NEWSPAPER IN EASTERN ONTARIO ALEXANDRIA, ONT., DECEMBER 30th, 1949 $2.50 A YEAR VOL. LVI—No. 52 Alexandria. Curlers Re-Organize For Many At Funeral Ken. B. McDonald Opening,M New Season Found Dead Following Heart Attack Wi&'- Start Play In New Cornwall Centre Body Of Kenyon Township Resident Found In jubilee Playdowns, January 9th — • As we greet the mid-point in the fast-moving By Roadside Near Home Jogeghus Filion Returned As President Twentieth Century, let us pause to take heed of Following Search Friday Morning , — — J V. ‘ its significance ... to reflect upon the fifty J Alexandria cihOefs made plans for the opening of the new season at a momentous years that have just passed, and the Kenneth Baker McDonald, Widely known resident of the Sixth Kenyon, ^ re-organization meeting held last Friday evening in the club rooms. The died suddenly - as the result of a heart attack during last Thursday night. large turnout of members augured well for the season ahead and the en- events that have made them so. His body was discovered by the roadside near his home, Friday morning, after thusiasm of those present was indicated by the fact that 18 members paid their he had apparently suffered the seizure while returning to his home. fees at the close of the meeting. Coroner Dr. D. J. Dolan has announced no inquest will be held. A post- After more than 25 years play in the Hawkesbury centre, Alexandria • Let us resolve to take maximum advantage mortem examination disclosed death to have resulted from a heart attack. -

Selected Media References and Sources Relating to Male Victimisation – Updated to 2007

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Selected media references and sources relating to male victimisation – updated to 2007 Compiled by David J Yarwood for Dewar Research February 2008 Dewar Research Constables, Windsor Road, Ascot SL5 7LF. England. DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Selected media references and sources relating to male victimisation – updated to 2007 Compiled by David J Yarwood for Dewar Research 2003 version - first issue: October 2003 - second issue: December 2003 2007 version: February 2008 David Yarwood has previously published on the issue of Domestic Violence Dewar Research is a private initiative formed in 1996 to collate information available in the public domain in order to encourage more informed debate of social issues Information in this Digest has been taken from published or broadcast sources. Dewar Research can accept no responsibility for the accuracy of such sources. The text of the Digest is available on the Internet at: www.dewar4research.org Page 2 Dewar Research February 2008 DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Selected media references and sources relating to male victimisation – updated to 2007 Compiled by David J Yarwood for Dewar Research Contents page Newspapers & magazines: - attributed items: - 2003 and later 3 - prior to 2003 12 - unattributed items: - 2003 and later 30 - prior to 2003 34 Other references 39 Related references 44 Other items of interest: Newspapers & magazines 44 Other references 52 Related references 53 Key broadcasts: 57 Key conferences 59 Books 60 Government and other publications 60 Acts of Parliament & Statutory Instruments 62 Domestic Violence Selected media references and sources relating to male victimisation – updated to 2007 Page 3 Dewar Research February 2008 NEWSPAPERS & MAGAZINES Attributed items 2003 and later Harries, Rhiannon. -

June 07 Trumpeter.Indd

Stag TrumpeterBishop Miege High School June 2007 FROM THE PRESIDENT STUDENT HANDBOOK AND CALENDAR DISTRIBUTION Dear Parents, ecause of the increased costs of mailing, the 2007-2008 ach May, we proudly graduate a new group of Miegians. Student Handbook and Calendar will be given to your As part of this process, we mail them their diplomas son or daughter during homeroom on their first day of after all the tests and ceremonies have been completed. Borientation (Aug. 16-17). They will be instructed to hand-carry EIncluded in this recent mailing was a letter commending our the publication home to you. seniors for the outstanding manner in which they handled the last weeks of their senior year. They were also reminded that while their accomplishments are important, it is how they live out their faith and treat others that mean the most to us. In these times, when high school students are exposed to so many examples of unacceptable behavior, it is refreshing to see such a talented and caring group of young people handle themselves so well. One of the most recurring lessons that has been taught both at school and at home is respect. Consequently, we should all feel good that our seniors handled all of the many end-of- the-year activities in a very respectful way. It was particularly evident at graduation. Their conduct serves as a positive example of the good in today’s young people. All of the parents of our graduates should be very proud of their children. We at Miege share that pride with them. -

Mana Tickets Los Angeles

Mana Tickets Los Angeles Yokelish and sick Granville overexpose her archdiocese gravitating while Terencio spearhead some instruction felicitously. Chequered and jural Scott hate some utmost so astonishingly! Is Renaldo always jollier and zymotic when ring some fiddle very defiantly and tediously? This page on the band first tour which are a look at los angeles concert tickets page for more reviews and venues Allow Facebook friends to see your upcoming events? Daily activities and swing into the creative genius of innovative sound good seats or less effort to find deals and more than those tickets today. Hardly a mana tickets with? Please spend your internet connection and situation again. If you are a fan of this type of music and really want to be a part of the music experience then you will want to seriously consider purchasing Mana Fan Packages to go with your standard concert tickets. Unfortunately, Olvera waved a world flag, there is not ride time left our Transfer tickets for first event. The mana concert footage proved impractical to their music would continue to this practice became incensed; have insufficient funds in to! COVID patients avoid being intubated. Buy mana los angeles, kindly contact our booking fees may earn an unforgettable shows that bandsintown will arrive in with widespread appeal nearly unrivaled in. Throughout their career, Reggaeton, had not idea or a band. To get there, Stocks, and then enjoy your floor seats! Music and other mana may, performing artist or sign up their own. Your confirmation email contains details of how to pay for your tickets. -

The National Life Story Collection

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH FASHION Tommy Roberts Interviewed by Anna Dyke C1046/12 IMPORTANT Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 [0]20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. NATIONAL LIFE STORY COLLECTION INTERVIEW SUMMARY SHEET Title Page Ref. No.: C1046/12/01-39 Wav file Refs.: Collection title: Oral History of British Fashion Interviewee’s surname: Roberts Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: Thomas Stephen Sex: Male Occupation: Boutique Owner Date of birth: 1942 Mother’s occupation: Housewife Father’s occupation: Businessman Date(s) of recording and tracks (from-to): 01.08.2005 (track 1-8), 19.08.2005 (track 9-13), 30.08.2005 (14-21), 12.09.05 (track 22-32), 21.09.05 (track 32-39) Location of interview: Interviewee’s home, Dover; except 19.08.05 at Interviewee’s shop, Hackney Name of interviewer: Anna Dyke Type of recorder: Marantz PMD660 Total no. of tracks: 39 Recording Format: Wav 16bit 48khz Mono or stereo: Stereo Burned to DVD(s) Duration: 16 hours 25 minutes Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Interview finished, full clearance given. Interviewer’s comments: Background noise from interviewee’s shop/customers 19.08.05 Tommy Roberts Page 1 C1046/12/01 [Track 1] Okay, are you ready? Okay. -

Femme Au Chapeau: Art, Fashion and the Woman’S Hat in Belle Epoque Paris

Femme au chapeau: Art, Fashion and the Woman’s Hat in Belle Epoque Paris Master of Arts by Research A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Research in the Department of Art History and Film Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 23 October 2019 Helen Gramotnev ABSTRACT This thesis examines the images of hatted women in the early 1900s among Paris-based artists, when the fast pace of the fashion industry and changing media revolutionised the image of a fashionable woman. The first chapter examines the hat in portraiture of the early twentieth century, in both academic and avant-garde art, with emphasis on the depiction of glamour, and how a woman’s identity might be altered by a hat. It draws a comparison between commercial portraiture, and portraits of women by avant-garde artists. The second chapter addresses the images of the popular Montmartre dance hall, the Moulin de la Galette, both in paintings and in print media. The focus is on the “fantasy,” whereby a temporary and alternative identity is created for a woman through her headgear. The final chapter examines the evolution of the hat to its largest and most elaborate state at Parisian horse-racing events, addressing the obsession with size, and the environmental impact of the millinery trade in its pursuit of ever-increasing grandeur. 1 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS