UNSTITCHING the 1950S FILM Á COSTUMES: HIDDEN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B Rig H to N E X P Lo Re Rs C Lu B

The Brighton Explorers Club (Est 1967) www.brightonexplorers.org email: [email protected] BEC SAFETY GUIDELINES CONTENTS Page 1 BEC SPORTS ACTIVITIES IN GENERAL 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Personal Details 2 1.3 Incident Book 2 1.4 Club Equipment 2 1.5 Group Size and Solo Activity 3 1.6 Looking Out For One Another 3 1.7 Mobile Phones 3 1.7.1 ‘ICE’: A Message from the Ambulance Service 1.7.2 Emergency Number 112 2 OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES 4 2.1 General Points 4 2.2 Natural Hazards 4 2.2.1 Dogs and cattle 2.2.2 Insects 2.2.3 Ticks and Lyme Disease 3 LEADING BEC ACTIVITIES 6 4 CAVING GUIDELINES 7 5 CLIMBING GUIDELINES 8 6 COASTEERING GUIDELINES 10 7 CYCLING GUIDELINES 12 7.1 Guidance Notes for Leading Cycle Rides 13 8 KAYAKING GUIDELINES 15 9 SURFING GUIDELINES 18 10 WALKING GUIDELINES 21 11 WINDSURFING GUIDELINES 24 APPENDIX 1: BASIC FIRST AID KIT 26 Brighton Explorers Club Last updated: 11th Jan 15 The Brighton Explorers Club is a UK registered charity. Charity no. 1156361 Page 1 of 26 BEC SAFETY GUIDELINES 1. BEC SPORTS ACTIVITIES IN GENERAL 1.1 Introduction Brighton Explorers Club (BEC) exists to encourage members to enjoy a variety of sporting pursuits; BEC is a club and not an activity centre, where the activities promoted by BEC can be dangerous if undertaken without consideration for the appropriate safety requirements. BEC is committed to maintaining high standards of safety. This document defines reasonable precautions to ensure that activities are carried out under safe conditions; to encourage all members to participate in club activities in a safe manner. -

1ST HINCHLEY WOOD SCOUT TROOP - EQUIPMENT LIST You Will Need to Provide Personal Equipment for Camping, Outdoor Activities Etc

1ST HINCHLEY WOOD SCOUT TROOP - EQUIPMENT LIST You will need to provide personal equipment for camping, outdoor activities etc. as listed below. We are happy to advise on equipment selection and suppliers etc. Most offer discounts to Scouts, do not be afraid to ask! Loss of or damage to personal property of Group members (only) when on Scout activities is covered by an insurance policy held by the Group. Cover is to a maximum of £400 per individual (£200 max each item, excess £15) and is subject to exclusions (details on request). We sometimes do have some second hand items (eg hike boots) for loan, please ask! Please mark everything possible (especially uniform) with your name in a visible place! NORMAL CAMP KIT ------------------------------- CANOEING/KAYAKING KIT---------------------- Rucsac, Kit Bag or holdall to contain your kit (please do not bring your kit in bin liners!) T-Shirt Sweatshirt Day Sac (useful for travelling & activities off Swimming Shorts site). Bring one with two shoulder straps. Waterproof Top (Cagoule) Normal Scout Uniform Waterproof Overtrousers (for canoeing) Wire Coat Hanger (to hang uniform in tent) Canvas Shoes/old Trainers/wet suit shoes Plenty of warm clothes: Towel & change of clothes inc shoes Underclothes, Handkerchiefs Carrier bag for wet kit T-Shirts, Sweatshirts/Jumpers, Fleece HIKING KIT -------------------------------------------- Shorts, Trousers, Jeans Shoes &/or Trainers Day Sac – a comfortable one big enough for what you have to carry but not huge! Bring one with two shoulder Sleeping mat (optional -

Dossier De Presse ECLAIR

ECLAIR 1907 - 2007 du 6 au 25 juin 2007 Créés en 1907, les Studios Eclair ont constitué une des plus importantes compagnies de production du cinéma français des années 10. Des serials trépidants, des courts-métrages burlesques, d’étonnants films scientifiques y furent réalisés. Le développement de la société Eclair et le succès de leurs productions furent tels qu’ils implantèrent des filiales dans le monde, notamment aux Etats-Unis. Devenu une des principales industries techniques du cinéma français, Eclair reste un studio prisé pour le tournage de nombreux films. La rétrospective permettra de découvrir ou de redécouvrir tout un moment essentiel du cinéma français. En partenariat avec et Remerciements Les Archives Françaises du Film du CNC, Filmoteca Espa ňola, MoMA, National Film and Television Archive/BFI, Nederlands Filmmuseum, Library of Congress, La Cineteca del Friuli, Lobster films, Marc Sandberg, Les Films de la Pléiade, René Chateau, StudioCanal, Tamasa, TF1 International, Pathé. SOMMAIRE « Eclair, fleuron de l’industrie cinématographique française » p2-4 « 1907-2007 » par Marc Sandberg Autour des films : p5-6 SEANCE « LES FILMS D’A.-F. PARNALAND » Jeudi 7 juin 19h30 salle GF JOURNEE D’ETUDES ECLAIR Jeudi 14 juin, Entrée libre Programmation Eclair p7-18 Renseignements pratiques p19 La Kermesse héroïque de Jacques Feyder (1935) / Coll. CF, DR Contact presse Cinémathèque française Elodie Dufour - Tél. : 01 71 19 33 65 - [email protected] « Eclair, fleuron de l’industrie cinématographique française » « 1907-2007 » par Marc Sandberg Eclair, c’est l’histoire d’une remarquable ténacité industrielle innovante au service des films et de leurs auteurs, grâce à une double activité de studio et de laboratoire, s’enrichissant mutuellement depuis un siècle. -

L Inspecteur Leclerc Enquête

Les fiches du Rayon du Polar L Inspecteur Leclerc Enquête Editions virtuelles Le Rayon du Polar Page 1/12 Les fiches du Rayon du Polar Philippe Nicaud : l'inspecteur Leclerc (38 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| Paul Gay : l'inspecteur Galtier (37 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| André Valmy : l'inspecteur Denys (33 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| Robert Dalban : le divisionnaire Brunel (26 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| Anne Doat : Lucie (4 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| Teddy Bilis : Chef de la D.S.T. (3 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| Françoise Giret : Jacqueline (3 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| Claude Nicot : Renard (2 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| Marcel Pérès : L'accordéonniste (2 épisodes, 1962) ||| Georges Bever : L'employé du greffe (2 épisodes, 1962) ||| Jean Clarieux : Le patron (2 episodes, 1962) ||| Mireille Darc : Georgette (2 episodes, 1962-1963) ||| Perrette Pradier : Jacqueline (2 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| Raymond Bussières : José L'Arpince (2 épisodes, 1962-1963) ||| Françoise Fabian : Mme Gauthier (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Anouk Ferjac : Marthe (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Dany Saval : Françoise (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Jean Tissier : Le directeur (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Guy Tréjan : M. Gauthier (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Marcel Bozzuffi : Silone (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Jackie Sardou : La Concierge (1 épisode, 1962) ||| André Rousselet : L'assistant du laboratoire (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Jean-Pierre Kalfon : Lupo (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Jean-Pierre Marielle : Michel Duquesnoy (1 épisode, 1963) ||| Henri Crémieux : Me Vincent (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Dora Doll : Ginette (1 épisode, 1962) ||| Jean Galland -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Catalogue-2018 Web W Covers.Pdf

A LOOK TO THE FUTURE 22 years in Hollywood… The COLCOA French Film this year. The French NeWave 2.0 lineup on Saturday is Festival has become a reference for many and a composed of first films written and directed by women. landmark with a non-stop growing popularity year after The Focus on a Filmmaker day will be offered to writer, year. This longevity has several reasons: the continued director, actor Mélanie Laurent and one of our panels will support of its creator, the Franco-American Cultural address the role of women in the French film industry. Fund (a unique partnership between DGA, MPA, SACEM and WGA West); the faithfulness of our audience and The future is also about new talent highlighted at sponsors; the interest of professionals (American and the festival. A large number of filmmakers invited to French filmmakers, distributors, producers, agents, COLCOA this year are newcomers. The popular compe- journalists); our unique location – the Directors Guild of tition dedicated to short films is back with a record 23 America in Hollywood – and, of course, the involvement films selected, and first films represent a significant part of a dedicated team. of the cinema selection. As in 2017, you will also be able to discover the work of new talent through our Television, Now, because of the continuing digital (r)evolution in Digital Series and Virtual Reality selections. the film and television series industry, the life of a film or series depends on people who spread the word and The future is, ultimately, about a new generation of foreign create a buzz. -

May 2019 Digital

MAY 2019 80 YEARS OF CINEMA MAY 2019 MAY GLASGOWFILM.ORG | 0141 332 6535 CINEMASTERS: HIROKAZU KORE-EDA | ITALIAN FILM FESTIVAL | HIGH LIFE 12 ROSE STREET, GLASGOW, G3 6RB WOMAN AT WAR | TOLKIEN | VOX LUX | FINAL ASCENT | AMAZING GRACE CONTENTS Access Film Club: Eighth Grade 20 Nobody Knows 9 The Straight Story - 35mm 8 Amazing Grace 13 Shoplifters 10 MOVIE MEMORIES Arctic 14 Still Walking 9 Rebecca 19 Ash Is Purest White 15 CINEMASTERS: Rebel Without a Cause 19 Beats 14 STANLEY KUBRICK SCOTTISH MENTAL HEALTH Birds of Passage 14 2001: A Space Odyssey 10 ARTS FESTIVAL Dead Good 5 Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to 10 Evelyn + Skype Q&A 8 Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb Donbass 15 Irene’s Ghost + Q&A 8 13 Full Metal Jacket 10 Eighth Grade SPECIAL EVENTS Final Ascent 13 EVENT CINEMA Asbury Park: 6 Have You Seen My Movie? 13 Bolshoi Ballet: Carmen Suite/Petrushka 18 Riot, Redemption, Rock ‘n’ Roll High Life 14 Margaret Atwood: Live in Cinemas 18 Cléo from 5 to 7 6 The Keeper 15 NT Live: All My Sons 18 Crossing the Line: Al Ghorba: 6 Madeline’s Madeline 14 NT Live Encore: One Man, Two Guvnors 18 Be:Longing in Britain The Thing 14 NT Live: The Lehman Trilogy 18 Dead Good + Q&A 5 Tolkien 15 NT Live: Small Island 18 Inquiring Nuns + Skype Q&A 7 Neither Wolf Nor Dog + Q&A 7 @glasgowfilm Too Late to Die Young 15 ITALIAN FILM FESTIVAL Visible Cinema: Edie 20 Capri-Revolution 11 Preview: Freedom Fields + Q&A 6 Vox Lux 13 The Conformist 11 Preview: In Fabric + Q&A 7 Woman at War 13 Daughter of Mine 12 Preview: Sunset - 35mm + Q&A 5 XY Chelsea 15 -

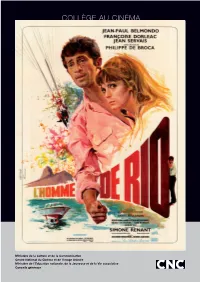

Collège Au Cinéma

COLLÈGE AU CINÉMA Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée Ministère de l’Education nationale, de la Jeunesse et de la Vie associative Conseils généraux L’Homme de Rio France, 1963, 35mm, couleurs, 1h52’. Philippe de Broca Réal : Philippe de Broca. Scén. : Philippe de Broca, Daniel Boulanger, NAISSANCE DU FILM Ariane Mnouchkine, Jean-Paul Rappeneau Philippe de Broca de Ferrussac, descendant de nobles gascons, naît en 1933 Prod. : Alexandre Mnouchkine, à Paris. Son grand-père, peintre, son père photographe, lui transmettent un Georges Dancigers goût pour l’imaginaire. L’invention permet l’évasion, qui devient désir concret Interprétation : de voyager. Après une formation d’opérateur à l’École Louis Lumière, fraî- Adrien Dufourquet (Jean-Paul Belmondo), Agnès chement diplômé à 19 ans, il s’embarque pour l’Afrique avec l’expédition Villermosa (Françoise Dorléac), Professeur Citroën-Bosch Lavalette et commence sa vraie vie d’aventurier, caméra au Catalan (Jean Servais)… poing. Le service militaire l’entraîne en Algérie, en pleine guerre. Confronté à une réalité violente, il s’accroche au cinéma comme remède contre les tragé- dies. Un coup de chance lui permet de devenir l’assistant de Claude Chabrol, qui l’engage pour plusieurs films, et de rencontrer Jean-Paul Belmondo en 1959. Chabrol lui signe un chèque pour qu’il puisse se lancer à son tour dans la réalisation. Philippe de Broca tourne alors coup sur coup trois comédies sentimentales, qui mettent en avant la spontanéité des personnages, plus atta- chants, plus vrais et plus complexes que de simples figures comiques. -

LE TEMPS DES NABABS Une Série Documentaire De Florence Strauss Les Films D’Ici Et Le Pacte Présentent

COMMENT PRODUISAIT-ON AVANT LA TÉLÉVISION ? LE TEMPS DES NABABS Une série documentaire de Florence Strauss Les Films d’Ici et Le Pacte présentent COMMENT PRODUISAIT-ON AVANT LA TÉLÉVISION ? LE TEMPS DES NABABS Une série documentaire de Florence Strauss 8 x 52min – France – 2019 – Flat - stéréo À PARTIR DU 12 OCTOBRE SUR CINÉ + CLASSIC RELATIONS PRESSE Marie Queysanne Assistée de Fatiha Zeroual Tél. : 01 42 77 03 63 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS LISTE DES ÉPISODES Pierre Braunberger, Anatole Dauman, Robert Dorfmann, les frères ÉPISODE 1 : LES ROMANESQUES Hakim, Mag Bodard, Alain Poiré, Pierre Cottrell, Albina du Boisrouvray, Robert et Raymond Hakim - Casque d’Or Jacques Perrin, Jean-Pierre Rassam et bien d’autres… Ils ont toujours André Paulvé - La Belle et la Bête oeuvré dans l’ombre et sont restés inconnus du grand public. Pourtant Alexandre Mnouchkine et Georges Dancigers - Fanfan La Tulipe ils ont produit des films que nous connaissons tous, deLa Grande Henri Deutschmeister - French Cancan vadrouille à La Grande bouffe, de Fanfan la tulipe à La Maman et la putain, de Casque d’or à La Belle et la bête. ÉPISODE 2 : LES TENACES Robert Dorfmann - Jeux interdits Autodidactes, passionnés, joueurs, ils ont financé le cinéma avec une Pierre Braunberger - Une Histoire d’eau inventivité exceptionnelle à une époque où ni télévisions, ni soficas ou Anatole Dauman - Nuit et brouillard autres n’existaient. Partis de rien, ils pouvaient tout gagner… ou bien tout perdre. Ce sont des personnages hauts en couleur, au parcours ÉPISODE 3 : LES AUDACIEUX souvent digne d’une fiction. -

STUDIA CARACOANA. Etudes Sur Albert Caraco, Réunies Par Philippe Billé Table : Quelques Remarques, Par Ph. Billé Remarks Abou

STUDIA CARACOANA. Etudes sur Albert Caraco, réunies par Philippe Billé Table : Quelques remarques, par Ph. Billé Remarks about Caraco (version anglaise du précédent) Bibliographie d’Albert Caraco 1 : Chronologie des œuvres Bibliographie d’Albert Caraco 2 : Index des titres Bibliographie sur Albert Caraco Index du Semainier de l’agonie (1963) Traduction d’un portrait en espagnol de 1968 et d’un autre en anglais Fragments espagnols traduits du Semainier de 1969 Dix fragments espagnols traduits du Semainier de l’agonie (1963) Article et passage de Louis Nucéra Note de lecture sur Journal d’une année (1957-1958) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - QUELQUES REMARQUES SUR ALBERT CARACO, avec un tissu de citations par Philippe Billé «Je suis raciste et je suis colonialiste.» (Ma confession, p 141). Albert Caraco avait un certain talent pour mettre tout le monde à l’aise, d’entrée de page. C’était à bien des égards un écrivain hors du commun. A ce qu’on dit, il était né dans une famille séfarade à Constantinople, en 1919 (le 10 juillet d’après une notice, le 8 selon ses propres dires dans le Semainier de l’agonie, p 44). Il était le fils unique d’un banquier juif espagnol et d’une mère juive russe. Il vécut dans son enfance «entre Prague et Vienne» de 1920 à 1923, puis à Berlin de 1924 à 1929 (de 1926 à 29, habite au Kurfürstendamm, n° 199 ; en 29, donc à 10 ans, il ne parle que l’allemand) enfin de 1929 à 1939 à Paris, où il fut élève au lycée Janson-de-Sailly (en 1929-30 habite 47 boulevard Suchet, de 34 à 37 avenue Paul Doumer) (Journal d’une année). -

UK-Films-For-Sale-Filmart-2018.Pdf

3 Way Junction TBeta Cinema Cast: Tom Sturridge, Stacy Martin, Tommy Flanagan Tassilo Hallbauer Genre: Drama [email protected] Director: Juergen Bollmeyer Market Office: EFP Umbrella 1C-E14 Status: Completed Home Office tel: +49 89 67 34 69 828 Synopsis: Suffering from a massive career disappointment, London architect Carl Walters travels to the grand dunes of the Namibian Desert to escape. However, destiny soon strikes and he finds himself stranded alone in the African nowhere, desperately waiting for a ride that never comes. Carl embarks on a bitter rite of passage, a trial only overcome if he is willing to radically change his attitude towards life. In the face of his own demise, Carl learns the simple truth: To survive, you need to act. 6 Children And 1 Grandfather TPremiere Ent. Group Cast: John Savage, Burt Young, Blanca Blanco, Bret Roberts Gabby Axume Genre: Family [email protected] Director: Yann Thomas Market Office: 1C-B14 Status: Completed Home Office tel: +1 213 534 3139 Synopsis: One day can change everything All The Devil's Men TGFM Films Cast: Milo Gibson, Gbenga Akinnagbe, Sylvia Hoeks, Morgan Edoardo Bussi Spector, William Fichtner [email protected] Genre: Action/Adventure Market Office: UK Film Centre 1C-F22 Director: Matthew Hope Home Office tel: +44 20 7186 6300 Status: Completed Synopsis: A battle-scarred War on Terror bounty hunter is forced to go to London on a manhunt for a disavowed CIA operative, which leads him into a deadly running battle with a former military comrade and his private army. The -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Polacos, White Slaves, and Stille Chuppahs: Organized Prostitution and the Jews of Buenos Aires, 1890-1939 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bx304mn Author Yarfitz, Mir Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Polacos, White Slaves, and Stille Chuppahs: Organized Prostitution and the Jews of Buenos Aires, 1890-1939 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Mir Hayim Yarfitz 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Polacos, White Slaves, and Stille Chuppahs: Organized Prostitution and the Jews of Buenos Aires, 1890-1939 by Mir Hayim Yarfitz Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles Professor José C. Moya, Chair This dissertation explores the particularly prominent role of Jews in coercive sex trafficking, then called white slavery in Buenos Aires when it was considered to be the world capital. The project aims to de-exoticize the subject by comparing Jewish pimps and prostitutes to other immigrants, grounding them in the neighborhoods they lived in, exploring the concrete concerns of their opponents, and connecting the broader discourses around these issues to transnational conversations about migration, sexuality, and the significance of race, ethnicity, and nationhood – the establishment of the boundaries of whiteness – in the furor around white slavery. I introduce new evidence about the Zwi Migdal Society (also called the Varsovia Society), a powerful mutual aid ii and burial association of Jewish pimps based in the Argentine capital.