Volume 21, Full Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL HISTORICAL OUTLINE 1989-1990: Lieutenant Governor's Task Force on Rivers, Final Report & Recommendations, 58 Pages, February, 1990

RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL HISTORICAL OUTLINE 1989-1990: Lieutenant Governor's Task Force on Rivers, Final Report & Recommendations, 58 pages, February, 1990. 1991-2000: Governor Bruce Sundlun inaugurated January 1, 1991. General Assembly created RI Rivers Council (RC) – RI General Law 46-28. Kenneth Payne became RC chair. Statewide Planning Program provides staff support to RC. RC concluded in 1992 that "more effective integration of existing programs and authority for rivers is needed." RC formulated draft classifications for rivers in 1993. RC held four workshops in northern, central, southern and eastern RI in 1994 to refine draft river classifications. Governor Lincoln Almond inaugurated January 1, 1995. Michael Cassidy, Planner for the City of Pawtucket, became RC chair. RC, working with the Divison of Planning, created digital maps of the state's watersheds. The State Planning Council adopted the RI Rivers Policy and Classification Plan, in January 1998, as State Guide Plan Element 162. RC established policies for recognizing local watershed councils in 1998. The Blackstone, Saugatucket and Wood-Pawcatuck were first river systems to have watershed councils designated by RC. Note: Designated watershed councils have certain legal authority and standing to represent their water bodies in state and local jurisdictions as well as be eligible for state grants via RC. 2001-2007: Meg Kerr became RC chair. General Assembly commences in 2001 providing annual legislative grants to RC from $22,000 to $52,000 range. Annual grant rounds commence from RC to designated local watershed councils generally in $2,500 to $7,500 range from Fiscal Year 2002 to the present. -

Mythic Collection, LLC Form 253G1 Filed 2021-06-09

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 253G1 Filing Date: 2021-06-09 SEC Accession No. 0001477932-21-003906 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Mythic Collection, LLC Mailing Address Business Address 16 LAGOON CT. 16 LAGOON CT. CIK:1773026| IRS No.: 833427237 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 SAN RAFAEL CA 94903 SAN RAFAEL CA 94903 Type: 253G1 | Act: 33 | File No.: 024-10983 | Film No.: 211003855 415-335-6370 SIC: 5900 Miscellaneous retail Copyright © 2021 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Filed pursuant to Rule 253(g)(1) File No. 024-10983 OFFERING CIRCULAR DATED MAY 24, 2021 MYTHIC COLLECTION, LLC 16 LAGOON CT, SAN RAFAEL, CA 94903 (415-335-6370) Telephone Number www.mythicmarkets.com Best Efforts Offering of Series Membership interests Mythic Collection, LLC (“we,” “us,” “our,” “Mythic Collection” or the “Company”) is a Delaware series limited liability company whose core business is the identification, acquisition, marketing and management of vintage comic books, collectible cards and fantasy art. The Company is offering, on a best efforts basis, membership interests in each of the series of the Company listed in the “Series Offering Table” beginning on page 1 of this offering circular. All of the series of our company being offered may collectively be referred to in this offering circular as the “series” and each, individually, as a “series.” The interests of all series may collectively be referred to in this offering circular as the “interests” and each, individually, as an “interest” and the offerings of the interests may collectively be referred to in this offering circular as the “offerings” and each, individually, as an “offering.” See “Securities Being Offered” for additional information regarding the interests. -

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

Examining the Role of Political Language in Rhode Island's Health Care Debate

1 THE RHETORIC OF REFORM: EXAMINING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL LANGUAGE IN RHODE ISLAND’S HEALTH CARE DEBATE A dissertation presented by Kevin P. Donnelly to The Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Public and International Affairs Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts August 2009 2 THE RHETORIC OF REFORM: EXAMINING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL LANGUAGE IN RHODE ISLAND’S HEALTH CARE DEBATE by Kevin P. Donnelly ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public and International Affairs in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Northeastern University, August 2009 3 ABSTRACT Political language refers to the way in which public policy issues are portrayed, discussed, and ultimately perceived by the community at large. Focusing specifically on two case studies in Rhode Island—the efforts of two policy entrepreneurs to enact comprehensive health care reform, and Governor Donald Carcieri’s successful pursuit of a Medicaid “Global Waiver”—this thesis begins with a description of the social, political, and economic contexts in which these debates took root. Using a “framework of analysis” developed for this thesis, attention then centers on the language employed by the political actors involved in advancing health care reform, along with the response of lawmakers, organized interests, and the public. A major finding is that the use of rhetoric has been crucial to the framing of policy alternatives, constituency building, and political strategy within Rhode Island’s consideration of health care reform. -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

RWU School of Law Commencement (May 17, 2013) Roger Williams University School of Law

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Commencement (1996- ) Archives & Law School History 5-17-2013 RWU School of Law Commencement (May 17, 2013) Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/law_archives_commencement Recommended Citation Roger Williams University School of Law, "RWU School of Law Commencement (May 17, 2013)" (2013). Commencement (1996- ). Paper 18. http://docs.rwu.edu/law_archives_commencement/18 This Document is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Law School History at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement (1996- ) by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commencement Exercises ❧ May 17, 2013 Class of Two Thousand and Thirteen David A. Logan, Dean — Presiding Prelude .............................................. Prelude, Sigurd Jorasalfar by Edvard Grieg Processional .......................... Pipes and Drums by The Rhode Island Highlanders Pipe Band National Anthem .........................................................Rene de la Garza Introduction and Presentation of the Dean’s Distinguished Service Award .........David A. Logan Dean & Professor of Law President’s Remarks ..............................................Donald J. Farish, Ph.D., J.D. President, Roger Williams University Chairman’s Greetings ......................................................Mark S. Mandell RWU Trustee & Chairman of the Board of RWU Law Board of Directors Senior Partner, Mandell, Schwartz -

2009 Brown University Football Media Guide

2009 Brown University Football Media Guide 2009 Brown Co-Captain Paul Jasinowski ’10, David Howard ’10, First Team All-Ivy First Team All-Ivy 2009 Brown Football Schedule Defending Ivy League Champions 9/19 Sat. at Stony Brook .......... 6:00 p.m. 10/24 Sat. at Cornell ............. 12:30 p.m. 9/25 Fri. at Harvard .............. 7:00 p.m. 10/31 Sat. PENN ................ 12:30 p.m. 10/3 Sat. *RHODE ISLAND ....... 12:30 p.m. 11/7 Sat. at Yale ................ 12:30 p.m. 10/10 Sat. HOLY CROSS ........... 12:30 p.m. 11/14 Sat. DARTMOUTH .......... 12:30 p.m. 10/17 Sat. #PRINCETON (TV –Versus) 12:30 p.m. 11/21 Sat. at Columbia ............ 12:30 p.m. *Homecoming # Family Weekend Head Coach: Phil Estes 2009 Brown Football 2008 Ivy League Champions Brown Facts Contents Location ....................................................... Providence, RI 1 . ..Brownfacts Founded ............................................................. 1764 2 . ..AboutBrown President ..................................................... Ruth J. Simmons 4 . World Class Student-Athletes Enrollment ............................................................ 5,874 5 . Brown In TheCommunity Nickname ............................................................ Bears 6 . Success After Graduation Colors ........................................... Seal Brown, Cardinal Red, White 8 . Prominent BrownAlumni Stadium ..................................... Brown Stadium (20,000), Natural Grass 9 . .TheIvyLeague Director of Athletics .......................................... -

Mythic Collection, LLC Form 1-A POS Filed 2021-05

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 1-A POS Filing Date: 2021-05-10 SEC Accession No. 0001477932-21-002961 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Mythic Collection, LLC Mailing Address Business Address 16 LAGOON CT. 16 LAGOON CT. CIK:1773026| IRS No.: 833427237 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 SAN RAFAEL CA 94903 SAN RAFAEL CA 94903 Type: 1-A POS | Act: 33 | File No.: 024-10983 | Film No.: 21905554 415-335-6370 SIC: 5900 Miscellaneous retail Copyright © 2021 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document POST QUALIFICATION AMENDMENT TO OFFERING STATEMENT EXPLANATORY NOTE This is a post-qualification amendment no. 4 to an offering statement on Form 1-A originally filed by Mythic Collection, LLC (the “Company”) with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”) on July 31, 2019 and qualified by the SEC on August 5, 2019. The original offering statement was amended by post-qualification amendment no. 1, filed with the SEC on December 13, 2019 and qualified on April 28, 2020, post-qualification amendment no. 2, filed with the SEC on June 30, 2020 and qualified on July 20, 2020, and post-qualification amendment no. 3, initially filed with the SEC on January 7, 2021 and qualified on January 14, 2021. The purpose of this post-qualification amendment is to add to the offering circular contained within the offering statement, as amended and qualified, the audited financial statements of the Company for the year ended December 31, 2020, and to amend, update and/or replace certain information contained in the offering circular. -

Ken Mckay '06 Plans GOP Revival Roger Williams University School of Law

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Life of the Law School (1993- ) Archives & Law School History 6-22-2011 Newsroom: Ken McKay '06 Plans GOP Revival Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.rwu.edu/law_archives_life Recommended Citation Roger Williams University School of Law, "Newsroom: Ken McKay '06 Plans GOP Revival" (2011). Life of the Law School (1993- ). 264. https://docs.rwu.edu/law_archives_life/264 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Law School History at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Life of the Law School (1993- ) by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Newsroom Ken McKay '06 Plans GOP Revival This week's Providence Phoenix features a cover story on Ken McKay '06, who - the Phoenix asserts - may be just the man to revive the GOP in Rhode Island. From the PROVIDENCE PHOENIX : " The plan to turn Rhode Island red: GOP strategist Ken McKay is quietly plotting a data-driven explosion of the state’s one-party rule " by David Scharffenberg June 22, 2011: The Rhode Island Republican Party's reputation for ineptitude is, by any reasonable measure, richly deserved. Sure, the party held the governor's office for much of the last two decades. But no longer. Indeed, it doesn't claim a single statewide post at the moment. Its presence in the General Assembly has long been tiny. Its fundraising is anemic. And the GOP's hapless image only compounds the problem — making it difficult to attract the money and solid candidates that could resurrect the brand. -

Freepressreleasedb.Com

FreePressReleaseDB.com Records Fall for Vintage Comic Books in Bruneau & Co.'s Online-Only Spring Comic Book & Toy Auction Held April 4th Date : Apr 23, 2020 Offered were over 400 lots of rare graded comic books, key book lots, Marvel and D.C. comics and a fine collection of tin key wind, friction and battery-op Japanese robots and tin toys. Cranston, RI, USA, April 23, 2020 -- Record prices were shattered in an online-only Spring Comic Book & Toy Auction held April 4th by Bruneau & Co. Auctioneers, based in Cranston, along with Altered Reality Entertainment and Travis Landry, Bruneau & Co.’s Director of Pop Culture. Three copies of the comic book Tales to Astonish all brought record prices, for a combined $9,500. The top lot of the auction was a copy of Tales of Suspense #39 (Marvel Comics, March 1963), graded CGC 4.5 out of 10 for condition and featuring the origin and first appearance of Iron Man. The comic book had cream and off-white pages and came housed in a 12 ¾ inch by 8 inch CGC case. It went to a determined bidder for $9,250 – a record – falling just shy of five figures. The record-setting copies of Marvel Comics’ Tales to Astonish included Tales to Astonish #27 (Jan. 1962), featuring the first appearance of the Ant-Man, graded CGC 3.5 ($3,875); Tales to Astonish #13 (Nov. 1960), featuring the origin and first appearance of Groot, graded CGC 5.0 ($3,750); and Tales to Astonish #1 (Atlas Comics, Jan. -

Distinguishing Literal from Metaphorical Depictions of Exaggerated Size

Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences Volume 21 Issue 1 Article 41 2018 Structural and Contextual Frameworks: Distinguishing Literal from Metaphorical Depictions of Exaggerated Size Christopher A. Crawford Indiana University South Bend Igor Juricevic Indiana University South Bend Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jiass Recommended Citation Crawford, Christopher A. and Juricevic, Igor (2018) "Structural and Contextual Frameworks: Distinguishing Literal from Metaphorical Depictions of Exaggerated Size," Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 41. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jiass/vol21/iss1/41 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Structural and Contextual Frameworks: Distinguishing Literal from Metaphorical Depictions of Exaggerated Size* CHRISTOPHER A. CRAWFORD Indiana University South Bend IGOR JURICEVIC Indiana University South Bend ABSTRACT In 2016, the authors proposed the Contextual Framework and Structural Framework for understanding pictorial metaphors. These two dichotomous frameworks are especially useful for assessing the apprehension by viewers of pictorial devices that can be used either literally or metaphorically. One such pictorial device is exaggerated size—that is, depicting objects as being overly large. This pictorial device can be used metaphorically (e.g., to indicate importance) or literally (e.g., to depict a giant). We analyze three comic book covers from the Silver Age of American comic books using both frameworks to illustrate how observers distinguish metaphoric pictorial devices from literal ones. -

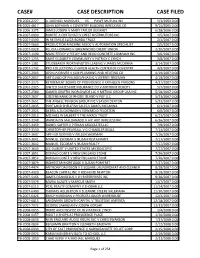

Case# Case Description Case Filed

CASE# CASE DESCRIPTION CASE FILED PB-2003-2227 A. MICHAEL MARQUES VS PAWT MUTUAL INS 5/1/2003 0:00 PB-2005-4817 JOHN BOYAJIAN V COVENTRY BUILDING WRECKING CO 9/15/2005 0:00 PB-2006-3375 JAMES JOSEPH V MARY TAYLOR DEVANEY 6/28/2006 0:00 PB-2007-0090 ROBERT A FORTUNATI V CREST DISTRIBUTORS INC 1/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0590 IN RE EMILIE LUIZA BORDA TRUST 2/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0663 PRODUCTION MACHINE ASSOC V AUTOMATION SPECIALIST 2/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0928 FELICIA HOWARD V GREENWOOD CREDIT UNION 2/20/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1190 MARC FEELEY V FEELEY AND REGO CONCRETE COMPANY INC 3/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1255 SAINT ELIZABETH COMMUNITY V PATRICK C LYNCH 3/8/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1381 STUDEBAKER WORTHINGTON LEASING V JAMES MCCANNA 3/14/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1742 PRO COLLECTIONS V HAVEN HEALTH CENTER OF COVENTRY 4/9/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2043 JOSHUA DRIVER V KLM PLUMBING AND HEATING CO 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2057 ART GUILD OF PHILADELPHIA INC V JEFFREY FREEMAN 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2175 RETIREMENT BOARD OF PROVIDENCE V KATHLEEN PARSONS 4/27/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2325 UNITED STATES FIRE INSURANCE CO V ANTHONY ROSCITI 5/7/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2580 GAMER GRAFFIX WORLDWIDE LLC V METINO GROUP USA INC 5/18/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2637 CITIZENS BANK OF RHODE ISLAND V PGF LLC 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2651 THE ANGELL PENSION GROUP INC V JASON DENTON 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2835 PORTLAND SHELLFISH SALES V JAMES MCCANNA 6/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2925 DEBRA A ZUCKERMAN V EDWARD D FELDSTEIN 6/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3015 MICHAEL W JALBERT V THE MKRCK TRUST 6/13/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3248 WANDALYN MALDANADO