Rhode Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL HISTORICAL OUTLINE 1989-1990: Lieutenant Governor's Task Force on Rivers, Final Report & Recommendations, 58 Pages, February, 1990

RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL HISTORICAL OUTLINE 1989-1990: Lieutenant Governor's Task Force on Rivers, Final Report & Recommendations, 58 pages, February, 1990. 1991-2000: Governor Bruce Sundlun inaugurated January 1, 1991. General Assembly created RI Rivers Council (RC) – RI General Law 46-28. Kenneth Payne became RC chair. Statewide Planning Program provides staff support to RC. RC concluded in 1992 that "more effective integration of existing programs and authority for rivers is needed." RC formulated draft classifications for rivers in 1993. RC held four workshops in northern, central, southern and eastern RI in 1994 to refine draft river classifications. Governor Lincoln Almond inaugurated January 1, 1995. Michael Cassidy, Planner for the City of Pawtucket, became RC chair. RC, working with the Divison of Planning, created digital maps of the state's watersheds. The State Planning Council adopted the RI Rivers Policy and Classification Plan, in January 1998, as State Guide Plan Element 162. RC established policies for recognizing local watershed councils in 1998. The Blackstone, Saugatucket and Wood-Pawcatuck were first river systems to have watershed councils designated by RC. Note: Designated watershed councils have certain legal authority and standing to represent their water bodies in state and local jurisdictions as well as be eligible for state grants via RC. 2001-2007: Meg Kerr became RC chair. General Assembly commences in 2001 providing annual legislative grants to RC from $22,000 to $52,000 range. Annual grant rounds commence from RC to designated local watershed councils generally in $2,500 to $7,500 range from Fiscal Year 2002 to the present. -

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

Examining the Role of Political Language in Rhode Island's Health Care Debate

1 THE RHETORIC OF REFORM: EXAMINING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL LANGUAGE IN RHODE ISLAND’S HEALTH CARE DEBATE A dissertation presented by Kevin P. Donnelly to The Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Public and International Affairs Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts August 2009 2 THE RHETORIC OF REFORM: EXAMINING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL LANGUAGE IN RHODE ISLAND’S HEALTH CARE DEBATE by Kevin P. Donnelly ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public and International Affairs in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Northeastern University, August 2009 3 ABSTRACT Political language refers to the way in which public policy issues are portrayed, discussed, and ultimately perceived by the community at large. Focusing specifically on two case studies in Rhode Island—the efforts of two policy entrepreneurs to enact comprehensive health care reform, and Governor Donald Carcieri’s successful pursuit of a Medicaid “Global Waiver”—this thesis begins with a description of the social, political, and economic contexts in which these debates took root. Using a “framework of analysis” developed for this thesis, attention then centers on the language employed by the political actors involved in advancing health care reform, along with the response of lawmakers, organized interests, and the public. A major finding is that the use of rhetoric has been crucial to the framing of policy alternatives, constituency building, and political strategy within Rhode Island’s consideration of health care reform. -

RWU School of Law Commencement (May 17, 2013) Roger Williams University School of Law

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Commencement (1996- ) Archives & Law School History 5-17-2013 RWU School of Law Commencement (May 17, 2013) Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/law_archives_commencement Recommended Citation Roger Williams University School of Law, "RWU School of Law Commencement (May 17, 2013)" (2013). Commencement (1996- ). Paper 18. http://docs.rwu.edu/law_archives_commencement/18 This Document is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Law School History at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement (1996- ) by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commencement Exercises ❧ May 17, 2013 Class of Two Thousand and Thirteen David A. Logan, Dean — Presiding Prelude .............................................. Prelude, Sigurd Jorasalfar by Edvard Grieg Processional .......................... Pipes and Drums by The Rhode Island Highlanders Pipe Band National Anthem .........................................................Rene de la Garza Introduction and Presentation of the Dean’s Distinguished Service Award .........David A. Logan Dean & Professor of Law President’s Remarks ..............................................Donald J. Farish, Ph.D., J.D. President, Roger Williams University Chairman’s Greetings ......................................................Mark S. Mandell RWU Trustee & Chairman of the Board of RWU Law Board of Directors Senior Partner, Mandell, Schwartz -

2009 Brown University Football Media Guide

2009 Brown University Football Media Guide 2009 Brown Co-Captain Paul Jasinowski ’10, David Howard ’10, First Team All-Ivy First Team All-Ivy 2009 Brown Football Schedule Defending Ivy League Champions 9/19 Sat. at Stony Brook .......... 6:00 p.m. 10/24 Sat. at Cornell ............. 12:30 p.m. 9/25 Fri. at Harvard .............. 7:00 p.m. 10/31 Sat. PENN ................ 12:30 p.m. 10/3 Sat. *RHODE ISLAND ....... 12:30 p.m. 11/7 Sat. at Yale ................ 12:30 p.m. 10/10 Sat. HOLY CROSS ........... 12:30 p.m. 11/14 Sat. DARTMOUTH .......... 12:30 p.m. 10/17 Sat. #PRINCETON (TV –Versus) 12:30 p.m. 11/21 Sat. at Columbia ............ 12:30 p.m. *Homecoming # Family Weekend Head Coach: Phil Estes 2009 Brown Football 2008 Ivy League Champions Brown Facts Contents Location ....................................................... Providence, RI 1 . ..Brownfacts Founded ............................................................. 1764 2 . ..AboutBrown President ..................................................... Ruth J. Simmons 4 . World Class Student-Athletes Enrollment ............................................................ 5,874 5 . Brown In TheCommunity Nickname ............................................................ Bears 6 . Success After Graduation Colors ........................................... Seal Brown, Cardinal Red, White 8 . Prominent BrownAlumni Stadium ..................................... Brown Stadium (20,000), Natural Grass 9 . .TheIvyLeague Director of Athletics .......................................... -

Ken Mckay '06 Plans GOP Revival Roger Williams University School of Law

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Life of the Law School (1993- ) Archives & Law School History 6-22-2011 Newsroom: Ken McKay '06 Plans GOP Revival Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.rwu.edu/law_archives_life Recommended Citation Roger Williams University School of Law, "Newsroom: Ken McKay '06 Plans GOP Revival" (2011). Life of the Law School (1993- ). 264. https://docs.rwu.edu/law_archives_life/264 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Law School History at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Life of the Law School (1993- ) by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Newsroom Ken McKay '06 Plans GOP Revival This week's Providence Phoenix features a cover story on Ken McKay '06, who - the Phoenix asserts - may be just the man to revive the GOP in Rhode Island. From the PROVIDENCE PHOENIX : " The plan to turn Rhode Island red: GOP strategist Ken McKay is quietly plotting a data-driven explosion of the state’s one-party rule " by David Scharffenberg June 22, 2011: The Rhode Island Republican Party's reputation for ineptitude is, by any reasonable measure, richly deserved. Sure, the party held the governor's office for much of the last two decades. But no longer. Indeed, it doesn't claim a single statewide post at the moment. Its presence in the General Assembly has long been tiny. Its fundraising is anemic. And the GOP's hapless image only compounds the problem — making it difficult to attract the money and solid candidates that could resurrect the brand. -

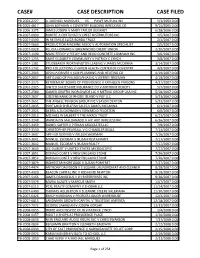

Case# Case Description Case Filed

CASE# CASE DESCRIPTION CASE FILED PB-2003-2227 A. MICHAEL MARQUES VS PAWT MUTUAL INS 5/1/2003 0:00 PB-2005-4817 JOHN BOYAJIAN V COVENTRY BUILDING WRECKING CO 9/15/2005 0:00 PB-2006-3375 JAMES JOSEPH V MARY TAYLOR DEVANEY 6/28/2006 0:00 PB-2007-0090 ROBERT A FORTUNATI V CREST DISTRIBUTORS INC 1/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0590 IN RE EMILIE LUIZA BORDA TRUST 2/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0663 PRODUCTION MACHINE ASSOC V AUTOMATION SPECIALIST 2/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0928 FELICIA HOWARD V GREENWOOD CREDIT UNION 2/20/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1190 MARC FEELEY V FEELEY AND REGO CONCRETE COMPANY INC 3/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1255 SAINT ELIZABETH COMMUNITY V PATRICK C LYNCH 3/8/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1381 STUDEBAKER WORTHINGTON LEASING V JAMES MCCANNA 3/14/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1742 PRO COLLECTIONS V HAVEN HEALTH CENTER OF COVENTRY 4/9/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2043 JOSHUA DRIVER V KLM PLUMBING AND HEATING CO 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2057 ART GUILD OF PHILADELPHIA INC V JEFFREY FREEMAN 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2175 RETIREMENT BOARD OF PROVIDENCE V KATHLEEN PARSONS 4/27/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2325 UNITED STATES FIRE INSURANCE CO V ANTHONY ROSCITI 5/7/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2580 GAMER GRAFFIX WORLDWIDE LLC V METINO GROUP USA INC 5/18/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2637 CITIZENS BANK OF RHODE ISLAND V PGF LLC 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2651 THE ANGELL PENSION GROUP INC V JASON DENTON 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2835 PORTLAND SHELLFISH SALES V JAMES MCCANNA 6/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2925 DEBRA A ZUCKERMAN V EDWARD D FELDSTEIN 6/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3015 MICHAEL W JALBERT V THE MKRCK TRUST 6/13/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3248 WANDALYN MALDANADO -

Civil Rights and Civil Wrongs in the Governor's Office

CIVIL RIGHTS AND CIVIL WRONGS IN THE GOVERNOR’S OFFICE: GOVERNOR DONALD CARCIERI’S FIRST SIX MONTHS IN OFFICE AND HIS RECORD ON CIVIL RIGHTS A REPORT PREPARED BY THE R.I. CIVIL RIGHTS ROUNDTABLE, R.I. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PROFESSIONALS, AND THE R.I. AFFILIATE, AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION August 2003 2 CIVIL RIGHTS AND CIVIL WRONGS IN THE GOVERNOR’S OFFICE: GOVERNOR DONALD CARCIERI’S FIRST SIX MONTHS IN OFFICE AND HIS RECORD ON CIVIL RIGHTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 1 The Issues . 3 Judicial Appointments . 3 Racial Profiling . 5 North Smithfield and the Fair Employment Practices Act . 6 The Narragansett Indian Smoke Shop Raid . 8 Immigrants and Drivers’ Licenses . 9 Recommendations . 13 Footnotes . 16 Supporting Organizations . 17 INTRODUCTION When the videotape of the July 14th State Police raid on the Narragansett Indian smoke shop was broadcast nationwide, Rhode Island Governor Donald Carcieri was subjected to a torrent of critical commentary. The images of a line of troopers bursting past tribal members, a police dog nipping at a person sprawled on the ground, and the wife of a tribal council member lying handcuffed in a fetal position with troopers looming over her were impossible to ignore. But the analogies many people made to images from the civil rights movement in the South in the 1960’s and depictions in films like “Mississippi Burning” missed a larger point. Governor Carcieri’s ill-advised approval of a raid on tribal land by state police was only the latest in a string of actions he has taken that have demonstrated both an insensitivity to the legitimate rights and expectations of people of color in Rhode Island and an enormous lack of interest in considering their viewpoint before making decisions that may have tremendous negative consequences for them. -

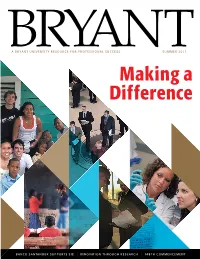

Making a Difference, an Achievement- and Action-Oriented Perspective Which Is Central to the Ethos of the Entire Bryant Community

A BR y A nt UnivERSity RESo URc E foR PR ofESSionA l SU ccESS SUMMER 2011 september 23-25 Making a Reunion Difference Homecoming @ Visit www.bryant.edu/reunion for details. in a tradition that began shortly after Bryant’s move from Providence to Smithfield, Ri, the Bryant community recently joined together for the 34th Annual festival of lights. the celebration of holidays from around the world included a candlelight procession that began in the Koffler Rotunda (pictured), and ended with a celebratory tree and menorah lighting at the Machtley interfaith center. BA nco SA ntA ndER SUPPo Rt S Si E innovAtion thR o U gh RESEARch 148 th co MMEncEMEnt 210723.C.indd 2 7/27/11 5:19 PM sUMMer 2011, VOLUMe 18 , nUMBer 2 You’re part of Make Bryant PUBLisHer PrOjeCt COOrdinatOr Bryant’s legacy. part of yours. Bryant University Office of Leslie Bucci ’77 1 24 University Advancement President’s Message PHiLantHrOPY in aCtiOn James Damron, Vice President design/PrOdUCtiOn A donation by Banco Santander supports for University Advancement Sandra Kenney Malcolm Grear Designers students’ access to the Sophomore PUBLisHing direCtOr International Experience program. Elizabeth O’Neil PHOtOgraPHY Victoria Arocheo As a Bryant graduate, you know that editOr Peter Goldberg Karen Maguire Don Hamerman 26 Richard Howard sPOtLigHt On: FaCULtY business is about more than debits and credits Managing editOr Matthew Lester 2 Faculty members are recognized Stasia B. Walmsley Pam Murray gaMe CHangers and that education takes you far beyond the Patrick O’Connor for excellence in teaching, research, COntriBUting Writers Doug Plummer Visionary alumni share their stories mentorship, and service. -

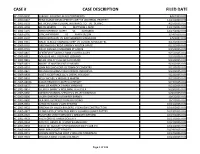

Case # Case Description Filed Date

CASE # CASE DESCRIPTION FILED DATE KC-1999-0600 SARAH E. FALLON D.M.D V CONTINENTA 8/6/1999 0:00 KC-2000-0867 RENAISSANCE DEVELOPMENT CORP VS UNIVERSAL PROPERTI 11/21/2000 0:00 KC-2001-0333 METROPOLITAN GENERAL INSURANCE CO. VS DEVIN C. 4/25/2001 0:00 KC-2001-1004 BRIAN MARTIN VS MATTHEW J. MAR 11/27/2001 0:00 KC-2002-1175 CHRISTOPHER M. DUFFY VS KATHLEEN 12/27/2002 0:00 KC-2003-0250 GERO MEYERSIEK VS MARY SEGUIN 3/24/2003 0:00 KC-2004-0104 JANICE BOYAJIAN VS EAST GREENWICH SEVEN 02 2/5/2004 0:00 KC-2004-0315 GREAT SENECA FINANCIAL CORP VS EUGENE M MCCAFFRE 4/12/2004 0:00 KC-2005-0555 GREENWOOD CREDIT UNION V WALTER VANCE 6/22/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0745 DAVID DANIELS V MAUREEN ST ANDRE 8/25/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0807 CENTREVILLE SAVINGS BANK V JOHN GAuVIN 9/15/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0812 DOUGLAS HALL V DONALD LOCKARD 9/15/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0815 BRIAN J DALEY V JILLIAN A JOHNSON 9/19/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0821 MICHELLE MARTIN V KELLY MCNEIL 9/20/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0824 JOHN ROCCHIO CORP VS TOWN OF COVENTRY 9/21/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0827 MELISSA ROLLINGS V NATIONWIDE INSURANCE 9/22/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0828 ASSET ACCEPTANCE LLC V CHERYL HOLLIDAY 9/22/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0831 KELLY MCNEIL V MICHELLE MARTIN 9/22/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0833A SUSAN BROWN V CAMELIA ALBRIGHT 9/23/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0837 BANK OF AMERICA V MARK VARDAKIS 9/23/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0857 STEPHEN BARRY V ROSEANNE THATCHER 9/29/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0860 INFINITI FINANCIAL SERVICES V KELLEY DONOVAN 9/30/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0890 LAURA GARDNER V JENNIFER BARNEY 10/6/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0892 BEATRICE REYNOLDS V RALPH PUCINO 10/7/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0910 CAROLYN WOOD V LORI STEVENS 10/13/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0922 GREENWICH VALLEY BUILDERS V SEAVIEW CONSTRUCTION 10/18/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0927 CLEAN CARE OF NEW ENGLAND V SOCARRO GOMEZ POTTER 10/19/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0929 RUMFORD CREDIT SERVICES V GREGORY GIFFORD 10/19/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0933 FRED FORD VS KAREN DOHERTY 10/21/2005 0:00 KC-2005-0934 PASCO V. -

Distinctive Collections at the University of Rhode Island Karen Walton Morse University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Creative Commons License

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Technical Services Faculty Presentations Technical Services 2017 Distinctive Collections at the University of Rhode Island Karen Walton Morse University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/lib_ts_presentations Recommended Citation Walton Morse, Karen, "Distinctive Collections at the University of Rhode Island" (2017). Technical Services Faculty Presentations. Paper 70. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/lib_ts_presentations/70https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/lib_ts_presentations/70 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Technical Services at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Services Faculty Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISTINCTIVE COLLECTIONS A presentation by Karen Walton Morse, 17 November 2017 Sponsored by the Library Faculty Development Committee Context Morse, K.W. Distinctive Collections at the University of Rhode Island, p.1 lecture sponsored by the University Library Faculty Development Commitee, Kingston, RI, November 17, 2017 Definitions Distinctive Collections: Special Collections (aka Special Collections and University Archives) by another name We: the core staff of Distinctive Collections ¾Karen Walton Morse, Director ¾Mark Dionne, Archivist ¾Student assistants, -

What's News at Rhode Island College Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC What's News? Newspapers 1-20-2003 What's News At Rhode Island College Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news Recommended Citation Rhode Island College, "What's News At Rhode Island College" (2003). What's News?. 36. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news/36 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in What's News? by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What’s News at Rhode Island College Vol. 23 Issue 6 Circulation over 46,000 Jan. 27, 2003 Highlights Oh, what a night! In the News RIC hosts Carcieri’s inaugural block party Jan. 7 RIC hosts Carcieri Inaugural Jan. 7 by Jane Fusco What's News Editor RIC nursing school ranks first in state Multi-cultural event cele– brated the diversity of the RIC student develops state’s 39 cities and towns with on-line daycare monitoring music, food, entertainment and system traditional favorites. hey came to meet the new gov- Features ernor, the state’s 57th. Nearly UConn professor to T5,000 Rhode Island residents gathered at the athletic complex on develop time-machine the Rhode Island College campus using laser technology Tuesday night, Jan. 7, to meet the man who promised change and vig- Nurse alum named Roger orous leadership for at least the next four years. Donald Carcieri, his Williams Hospital wife Suzanne M’93, and their large ‘Employee of the Year’ extended family, greeted the guests and invited them to enjoy food Alumni News and entertainment that reflected the multi-culturalism of the smallest RIC President John Nazarian (left) escorts state in the union.