The History and Geography of Recent Neotropical Mammals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifing Priority Ecoregions for Rodent Conservation at the Genus Level

Oryx Vol 35 No 2 April 2001 Short Communication Identifing priority ecoregions for rodent conservation at the genus level Giovanni Amori and Spartaco Gippoliti Abstract Rodents account for 40 per cent of living high number of genera) 'threat-spots' for rodent conser- mammal species. Nevertheless, despite an increased vation. A few regions, mainly drylands, are singled out interest in biodiversity conservation and their high as important areas for rodent conservation but are not species richness, Rodentia are often neglected by con- generally recognized in global biodiversity assessments. servationists. We attempt for the first time a world-wide These are the remaining forests of Togo, extreme evaluation of rodent conservation priorities at the genus 'western Sahel', the Turanian and Mongolian-Manchu- level. Given the low popularity of the order, we rian steppes and the desert of the Horn of Africa. considered it desirable to discuss identified priorities Resources for conservation must be allocated first to within the framework of established biodiversity prior- recognized threat spots and to those restricted-range ity areas of the world. Two families and 62 genera are genera which may depend on species-specific strategies recognized as threatened. Our analyses highlight the for their survival. Philippines, New Guinea, Sulawesi, the Caribbean, China temperate forests and the Atlantic Forest of Keywords Biodiversity, conservation priorities, south-eastern Brazil as the most important (for their rodents, threatened genera, world ecoregions. Conservation efforts for rodents must be included in Introduction the general framework of mammalian diversity conser- With 26-32 recognized extant families and more than vation, focusing on a biodiversity/area approach. -

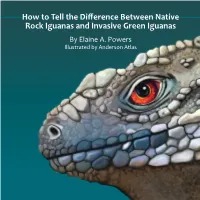

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

A Matter of Weight: Critical Comments on the Basic Data Analysed by Maestri Et Al

DOI: 10.1111/jbi.13098 CORRESPONDENCE A matter of weight: Critical comments on the basic data analysed by Maestri et al. (2016) in Journal of Biogeography, 43, 1192–1202 Abstract Maestri, Luza, et al. (2016), although we believe that an exploration Recently, Maestri, Luza, et al. (2016) assessed the effect of ecology of the quality of the original data informs both. Ultimately, we sub- and phylogeny on body size variation in communities of South mit that the matrix of body size and the phylogeny used by these American Sigmodontinae rodents. Regrettably, a cursory analysis of authors were plagued with major inaccuracies. the data and the phylogeny used to address this question indicates The matrix of body sizes used by Maestri, Luza, et al. (2016, p. that both are plagued with inaccuracies. We urge “big data” users to 1194) was obtained from two secondary or tertiary sources: give due diligence at compiling data in order to avoid developing Rodrıguez, Olalla-Tarraga, and Hawkins (2008) and Bonvicino, Oli- hypotheses based on insufficient or misleading basic information. veira, and D’Andrea (2008). The former study derived cricetid mass data from Smith et al. (2003), an ambitious project focused on the compilation of “body mass information for all mammals on Earth” We are living a great time in evolutionary biology, where the combi- where the basic data were derived from “primary and secondary lit- nation of the increased power of systematics, coupled with the use erature ... Whenever possible, we used an average of male and of ever more inclusive datasets allows—heretofore impossible— female body mass, which was in turn averaged over multiple locali- questions in ecology and evolution to be addressed. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

PROCEEDINGS OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM issued |o"«\N-^r S^toI ^y '^' SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION U.S. NATIONAL MUSEUM Vol. 110 Washington : I960 No. 3420 MAMMALS OF NORTHERN COLOMBIA, PRELIMINARY REPORT NO. 8: ARBOREAL RICE RATS, A SYSTEMATIC REVISION OF THE SUBGENUS OECOMYS, GENUS ORYZOMYS By Philip Hershkovitz'^ Arboreal rice rats are small to medium-sized cricetines of the genus Oryzomys (family Muridae). They are found only in tropical and subtropical zone forests of Central and South America. Of the two recognized species, the larger, Oryzomys (Oecomys) concolor, occurs in northern Colombia. The author collected 27 specimens from six localities during his 1941-43 tenure of the Walter Rathbone Bacon Traveling Scholarship and 38 specimens, including six of the smaller species, Oryzomys (Oecomys) bicolor, in other parts of Colombia while conducting the Chicago Natural History Museum-Colombian Zoological Expedi- tion (1949-52). This material and pertinent field observations are the basis of the present report. ' Previous reports in this series have been published in the Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum as follows: 1. Squirrels, vol. 97, August 2.5, 1947. 2. Spiny rats, vol. 97, January 6, 1948. 3. Water rats, vol. 98, Jime 30, 1948. 4. Monkeys, vol. 98, May 10, 1949. 5. Bats, vol. 99, May 10, 1949. fi. Rabbits, vol. 100, May 26. 19.50. 7. Tapirs, vol. 103, May 18, 1954. Curator of Mammals, Chicago Natural History Museum. 513 604676—59 1 514 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. uo Material A total of 390 specimens was studied. This number includes vir- tually all arboreal rice rats preserved in American museums, and the types only in the British Museum (Natural History). -

Local Companies Control Licenses

Org Name Lcl No T&B / Local Company Licence Start Date End Date Location File Number Description GRANT THORNTON SPECIALIST SERVICES 11/07 A Recovery And Reorganisation Practice Comprising The Provision Of Restructuring Advice Insolvency And 29-May-2007 29-May-2016 Block OPY Parcel 68/3, 2nd Floor Suite 4290, TB12650 Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) (CAYMAN) LIMITED Forensic Services 48 Market Street, George Town, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands MOORE STEPHENS DECOSIMO CAYMAN 32/05 Accountants 22-Nov-2005 22-Nov-2017 Block 12E, Parcel 106, Suite 200, Marquis TB9877 Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) LIMITED Place, West Bay, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands BDO CAYMAN LTD 07/11 Accounting And Auditing Services 29-Mar-2011 29-Mar-2023 23 Lime Tree Bay Avenue, Governor's Square, TB117AC Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) West Bay, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands SULA HOLDINGS LIMITED T/A BLUFF Agricultural Business Including Dairy Farming On Cayman Brac 24-Sep-2013 24-Sep-2025 Block 112A, Parcel 28, 30, 43, Cayman Brac, TB1095AB Agricultural production and Agrobased industries FARMS Cayman Islands JETBLUE AIRWAYS CORPORATION 07/12 Airline 04-Sep-2012 04-Sep-2024 Owen Roberts International Airport, 88C Owen TB705A Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) Roberts Drive, George Town, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands DELTA AIR LINES INC 09/11 Airline - Commercial Aircraft 26-Apr-2011 26-Apr-2023 Owen Roberts Airport, George Town, Grand TB6536 Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) Cayman US AIRWAYS INC 114311 Airline Agent 24-Aug-2010 24-Aug-2022 88C Owen Roberts Drive, George Town, Grand TB513A Local Company Control Law ( Annual Fee) Cayman, Cayman Islands RS&H INC. -

Biosystematics of the Native Rodents of the Galapagos Archipelago, Ecuador

539 BIOSYSTEMATICS OF THE NATIVE RODENTS OF THE GALAPAGOS ARCHIPELAGO, ECUADOR JAMES L. PATTON AND MARK S. HAFNER' Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 The native rodent fauna of the Galapagos Archipelago consists of seven species belonging to the generalized Neotropical rice rat (oryzomyine) stock of the family Cricetidae. These species comprise three rather distinct assemblages, each of which is varyingly accorded generic or subgeneric rank: (1) Oryzomys (sensu stricto), including 0. galapagoensis [known only from Isla San Cristobal] and 0. bauri [from Isla Santa Fe] ; (2) Nesoryzomys, including N. narboroughi [from Isla Fernandina], N. swarthi [from Isla Santiago], N. darwini [from Isla Santa Cruz] , and N. indefessus [from both Islas Santa Cruz and Baltra] ; and (3) Megalomys curioi [from Isla Santa Cruz]. Megalomys is only known from subfossil material and will not be treated here. Four of the remaining six species are now probably extinct as only 0. bauri and N. narboroughi are known cur- rently from viable populations. The time and pattern of radiation, and the phylogenetic relationships of Oryzomys and Nesoryzomys are assessed by karyological, biochemical, and anatomical investigations of the two extant species, and by multivariate morpho- metric analyses of existing museum specimens of all taxa. These data suggest the following: (a) Nesoryzomys is a very unique entity and should be recognized at the generic level; (b) there were at least two separate invasions of the islands with Nesoryzomys representing an early entrant followed considerably later by Oryzomys (s.s.); (c) both taxa of Oryzomys are quite recent immigrants and are probably derived from 0. -

Panama Canal with Princess Cruises® on the Crown Princess® 11 Days / 10 Nights ~ March 23 – April 2, 2022

GRUNDY COUNTY SENIOR CENTER PRESENTS PANAMA CANAL WITH PRINCESS CRUISES® ON THE CROWN PRINCESS® 11 DAYS / 10 NIGHTS ~ MARCH 23 – APRIL 2, 2022 DAY PORT ARRIVE DEPART 1 Ft. Lauderdale, Florida 4:00 PM 2 At Sea 3 Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands 7:00 AM 5:00 PM 4 At Sea 5 Cartagena, Colombia 7:00 AM 3:00 PM 6 Panama Canal Partial Transit New Locks 6:00 AM 3:30 PM 6 Cristobal, Panama 4:00 PM 7:00 PM 7 Limon, Costa Rica 7:00 AM 6:00 PM 8 At Sea 9 Falmouth, Jamaica 7:00 AM 3:00 PM 10 At Sea 11 Ft. Lauderdale, Florida 7:00 AM IF YOU BOOK BY OCTOBER 29, 2021 Inside Cabin Category IC $2,695 ONLY $100 pp DEPOSIT REQUIRED Outside Cabin Category OC $3,160 FOR DOUBLE OCCUPANCY Balcony Cabin Category BC $3,515 After 10/29/21 deposit is at least $350 pp * subject to capacity control* Rates are per person double occupancy and include roundtrip airfare PRINCESS PLUS from Kansas City, cruise, port charges, government fees, taxes and transfers to/from ship. PRINCESS CRUIES® HAS ADVISED THAT ALL FREE Premier Beverage Package AIR PRICES ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND ARE NOT FREE Unlimited Wi-Fi GUARANTEED UNTIL FULL PAYMENT HAS BEEN RECEIVED. FREE Prepaid Gratuities Offer applies to all guests in cabin. PASSPORT REQUIRED Offer is capacity controlled and subject to change. Please call for details DEPOSIT POLICY: An initial deposit of $350 per person double occupancy or $700 per person single occupancy is required in order to secure reservations and assign cabins. -

The Neotropical Region Sensu the Areas of Endemism of Terrestrial Mammals

Australian Systematic Botany, 2017, 30, 470–484 ©CSIRO 2017 doi:10.1071/SB16053_AC Supplementary material The Neotropical region sensu the areas of endemism of terrestrial mammals Elkin Alexi Noguera-UrbanoA,B,C,D and Tania EscalanteB APosgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Unidad de Posgrado, Edificio A primer piso, Circuito de Posgrados, Ciudad Universitaria, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), 04510 Mexico City, Mexico. BGrupo de Investigación en Biogeografía de la Conservación, Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), 04510 Mexico City, Mexico. CGrupo de Investigación de Ecología Evolutiva, Departamento de Biología, Universidad de Nariño, Ciudadela Universitaria Torobajo, 1175-1176 Nariño, Colombia. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Page 1 of 18 Australian Systematic Botany, 2017, 30, 470–484 ©CSIRO 2017 doi:10.1071/SB16053_AC Table S1. List of taxa processed Number Taxon Number Taxon 1 Abrawayaomys ruschii 55 Akodon montensis 2 Abrocoma 56 Akodon mystax 3 Abrocoma bennettii 57 Akodon neocenus 4 Abrocoma boliviensis 58 Akodon oenos 5 Abrocoma budini 59 Akodon orophilus 6 Abrocoma cinerea 60 Akodon paranaensis 7 Abrocoma famatina 61 Akodon pervalens 8 Abrocoma shistacea 62 Akodon philipmyersi 9 Abrocoma uspallata 63 Akodon reigi 10 Abrocoma vaccarum 64 Akodon sanctipaulensis 11 Abrocomidae 65 Akodon serrensis 12 Abrothrix 66 Akodon siberiae 13 Abrothrix andinus 67 Akodon simulator 14 Abrothrix hershkovitzi 68 Akodon spegazzinii 15 Abrothrix illuteus -

With Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2015-04-01 Evolution and Biogeography of Mesoamerican Small Mammals: With Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa Ana Villalba Almendra Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Villalba Almendra, Ana, "Evolution and Biogeography of Mesoamerican Small Mammals: With Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 5812. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5812 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Evolution and Biogeography of Mesoamerican Small Mammals: Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa Ana Laura Villalba Almendra A dissertation submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Duke S. Rogers, Chair Byron J. Adams Jerald B. Johnson Leigh A. Johnson Eric A. Rickart Department of Biology Brigham Young University March 2015 Copyright © 2015 Ana Laura Villalba Almendra All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Evolution and Biogeography of Mesoamerican Small Mammals: Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa Ana Laura Villalba Almendra Department of Biology, BYU Doctor of Philosophy Mesoamerica is considered a biodiversity hot spot with levels of endemism and species diversity likely underestimated. For mammals, the patterns of diversification of Mesoamerican taxa still are controversial. Reasons for this include the region’s complex geologic history, and the relatively recent timing of such geological events. -

I. G E O G RAP H IC PA T T E RNS in DIV E RS IT Y a . D Iversity And

I. GEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN DIVERSITY A. Diversity and Endemicty B. Patterns in Mammalian Richness 1 – latitude 2 – area 3 – isolation 4 – elevation C. Hotspots of Mammalian Biodiversity 1 – relevance 2 – optimal characteristics of hotspots 3 – empirical patterns for mammals II. CONSERVATION STATUS OF MAMMALS A. Prehistoric Extinctions B. Historic Extinctions 1 – summary (totals) 2 – taxonomic, morphologic bias 3 – Geographic bias C. Geography of Extinctions 1 – prehistory and human colonization 2 – geographic questions 3 – range collapse in mammals Hotspots of Mammalian Endemicity Endemic Mammals Species Richness (fig. 1) Schipper et al 2009 – Science 322:226. (color pdf distributed to lab sections) Fig. 2. Global patterns of threat, for land (brown) and marine (blue) mammals. (A) Number of globally threatened species (Vulnerable, Endangered or Critically Fig. 4. Global patterns of knowledge, for land Endangered). Number of species affected by: (B) habitat loss; (C) harvesting; (D) (terrestrial and freshwater, brown) and marine (blue) accidental mortality; and (E) pollution. Same color scale employed in (B), (C), (D) species. (A) Number of species newly described since and (E) (hence, directly comparable). 1992. (B) Data-Deficient species. Mammal Extinctions 1500 to 2000 (151 species or subspecies; ~ 83 species) COMMON NAME LATIN NAME DATE RANGE PRIMARY CAUSE Lesser Hispanolan Ground Sloth Acratocnus comes 1550 Hispanola introduction of rats and pigs Greater Puerto Rican Ground Sloth Acratocnus major 1500 Puerto Rico introduction of rats -

Investigating Evolutionary Processes Using Ancient and Historical DNA of Rodent Species

Investigating evolutionary processes using ancient and historical DNA of rodent species Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of London Royal Holloway University of London Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX Selina Brace November 2010 1 Declaration I, Selina Brace, declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, it is always clearly stated. Selina Brace Ian Barnes 2 “Why should we look to the past? ……Because there is nowhere else to look.” James Burke 3 Abstract The Late Quaternary has been a period of significant change for terrestrial mammals, including episodes of extinction, population sub-division and colonisation. Studying this period provides a means to improve understanding of evolutionary mechanisms, and to determine processes that have led to current distributions. For large mammals, recent work has demonstrated the utility of ancient DNA in understanding demographic change and phylogenetic relationships, largely through well-preserved specimens from permafrost and deep cave deposits. In contrast, much less ancient DNA work has been conducted on small mammals. This project focuses on the development of ancient mitochondrial DNA datasets to explore the utility of rodent ancient DNA analysis. Two studies in Europe investigate population change over millennial timescales. Arctic collared lemming (Dicrostonyx torquatus) specimens are chronologically sampled from a single cave locality, Trou Al’Wesse (Belgian Ardennes). Two end Pleistocene population extinction-recolonisation events are identified and correspond temporally with - localised disappearance of the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). A second study examines postglacial histories of European water voles (Arvicola), revealing two temporally distinct colonisation events in the UK. -

The Last Survivors: Current Status and Conservation of the Non-Volant Land

1 The Last Survivors: current status and conservation of the non-volant land 2 mammals of the insular Caribbean 3 4 SAMUEL T. TURVEY,* ROSALIND J. KENNERLEY, JOSE M. NUÑEZ-MIÑO, AND RICHARD P. 5 YOUNG 6 7 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY (STT) 8 Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Les Augrès Manor, Trinity, Jersey JE3 5BP, Channel 9 Islands (RJK, JNM, RPY) 10 11 *Correspondent: [email protected] 12 13 Running header: Status of Caribbean land mammals 14 1 15 The insular Caribbean is among the few oceanic-type island systems colonized by non-volant 16 land mammals. This region also has experienced the world’s highest levels of historical 17 mammal extinctions, with at least 29 species lost since AD 1500. Representatives of only 2 18 land-mammal families (Capromyidae and Solenodontidae) now survive, in Cuba, Hispaniola, 19 Jamaica, and the Bahama Archipelago. The conservation status of Caribbean land mammals 20 is surprisingly poorly understood. The most recent IUCN Red List assessment, from 2008, 21 recognized 15 endemic species, of which 13 were assessed as threatened. We reassessed all 22 available baseline data on the current status of the Caribbean land-mammal fauna within the 23 framework of the IUCN Red List, to determine specific conservation requirements for 24 Caribbean land-mammal species using an evidence-based approach. We recognize only 13 25 surviving species, 1 of which is not formally described and cannot be assessed using IUCN 26 criteria; 3 further species previously considered valid are interpreted as junior synonyms or 27 subspecies.