IGSF3 Mutation Identified in Patient with Severe COPD Alters Cell Function and Motility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Mechanisms of Blastic Transformation

Chronic myeloid leukemia: mechanisms of blastic transformation Danilo Perrotti, … , John Goldman, Tomasz Skorski J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2254-2264. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI41246. Science in Medicine The BCR-ABL1 oncoprotein transforms pluripotent HSCs and initiates chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Patients with early phase (also known as chronic phase [CP]) disease usually respond to treatment with ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), although some patients who respond initially later become resistant. In most patients, TKIs reduce the leukemia cell load substantially, but the cells from which the leukemia cells are derived during CP (so-called leukemia stem cells [LSCs]) are intrinsically insensitive to TKIs and survive long term. LSCs or their progeny can acquire additional genetic and/or epigenetic changes that cause the leukemia to transform from CP to a more advanced phase, which has been subclassified as either accelerated phase or blastic phase disease. The latter responds poorly to treatment and is usually fatal. Here, we discuss what is known about the molecular mechanisms leading to blastic transformation of CML and propose some novel therapeutic approaches. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/41246/pdf Science in medicine Chronic myeloid leukemia: mechanisms of blastic transformation Danilo Perrotti,1 Catriona Jamieson,2 John Goldman,3 and Tomasz Skorski4 1Department of Molecular Virology, Immunology and Medical Genetics and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA. 2Division of Hematology-Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 3Department of Haematology, Imperial College at Hammersmith Hospital, London, United Kingdom. 4Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Learning from Cadherin Structures and Sequences: Affinity Determinants and Protein Architecture

Learning from cadherin structures and sequences: affinity determinants and protein architecture Klára Fels ıvályi Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Klara Felsovalyi All rights reserved ABSTRACT Learning from cadherin structures and sequences: affinity determinants and protein architecture Klara Felsovalyi Cadherins are a family of cell-surface proteins mediating adhesion that are important in development and maintenance of tissues. The family is defined by the repeating cadherin domain (EC) in their extracellular region, but they are diverse in terms of protein size, architecture and cellular function. The best-understood subfamily is the type I classical cadherins, which are found in vertebrates and have five EC domains. Among the five different type I classical cadherins, the binding interactions are highly specific in their homo- and heterophilic binding affinities, though their sequences are very similar. As previously shown, E- and N-cadherins, two prototypic members of the subfamily, differ in their homophilic K D by about an order of magnitude, while their heterophilic affinity is intermediate. To examine the source of the binding affinity differences among type I cadherins, we used crystal structures, analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC), surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies. Phylogenetic analysis and binding affinity behavior show that the type I cadherins can be further divided into two subgroups, with E- and N-cadherin representing each. In addition to the affinity differences in their wild-type binding through the strand-swapped interface, a second interface also shows an affinity difference between E- and N-cadherin. -

The Transcriptomic Landscape of Prostate Cancer Development and Progression: an Integrative Analysis

cancers Article The Transcriptomic Landscape of Prostate Cancer Development and Progression: An Integrative Analysis Jacek Marzec 1,† , Helen Ross-Adams 1,*,† , Stefano Pirrò 1 , Jun Wang 1 , Yanan Zhu 2, Xueying Mao 2, Emanuela Gadaleta 1 , Amar S. Ahmad 3, Bernard V. North 3, Solène-Florence Kammerer-Jacquet 2, Elzbieta Stankiewicz 2, Sakunthala C. Kudahetti 2, Luis Beltran 4, Guoping Ren 5, Daniel M. Berney 2,4, Yong-Jie Lu 2 and Claude Chelala 1,6,* 1 Bioinformatics Unit, Centre for Cancer Biomarkers and Biotherapeutics, Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London, London EC1M 6BQ, UK; [email protected] (J.M.); [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (E.G.) 2 Centre for Cancer Biomarkers and Biotherapeutics, Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London, London EC1M 6BQ, UK; [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (X.M.); solenefl[email protected] (S.-F.K.-J.); [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (S.C.K.); [email protected] (D.M.B.); [email protected] (Y.-J.L.) 3 Centre for Cancer Prevention, Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Barts and the London School of Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, London EC1M 6BQ, UK; [email protected] (A.S.A.); [email protected] (B.V.N.) 4 Department of Pathology, Barts Health NHS, London E1 F1R, UK; [email protected] 5 Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University Medical College, Hangzhou 310058, China; [email protected] 6 Centre for Computational Biology, Life Sciences Initiative, Queen Mary University London, London EC1M 6BQ, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.R.-A.); [email protected] (C.C.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. -

Aneuploidy: Using Genetic Instability to Preserve a Haploid Genome?

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science (Cancer Biology) Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Submitted by: Ramona Ramdath In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science Examination Committee Signature/Date Major Advisor: David Allison, M.D., Ph.D. Academic James Trempe, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: David Giovanucci, Ph.D. Randall Ruch, Ph.D. Ronald Mellgren, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: April 10, 2009 Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Ramona Ramdath University of Toledo, Health Science Campus 2009 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandfather who died of lung cancer two years ago, but who always instilled in us the value and importance of education. And to my mom and sister, both of whom have been pillars of support and stimulating conversations. To my sister, Rehanna, especially- I hope this inspires you to achieve all that you want to in life, academically and otherwise. ii Acknowledgements As we go through these academic journeys, there are so many along the way that make an impact not only on our work, but on our lives as well, and I would like to say a heartfelt thank you to all of those people: My Committee members- Dr. James Trempe, Dr. David Giovanucchi, Dr. Ronald Mellgren and Dr. Randall Ruch for their guidance, suggestions, support and confidence in me. My major advisor- Dr. David Allison, for his constructive criticism and positive reinforcement. -

Genome-Wide Transcriptional Sequencing Identifies Novel Mutations in Metabolic Genes in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma DAOUD M

CANCER GENOMICS & PROTEOMICS 11 : 1-12 (2014) Genome-wide Transcriptional Sequencing Identifies Novel Mutations in Metabolic Genes in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma DAOUD M. MEERZAMAN 1,2 , CHUNHUA YAN 1, QING-RONG CHEN 1, MICHAEL N. EDMONSON 1, CARL F. SCHAEFER 1, ROBERT J. CLIFFORD 2, BARBARA K. DUNN 3, LI DONG 2, RICHARD P. FINNEY 1, CONSTANCE M. CULTRARO 2, YING HU1, ZHIHUI YANG 2, CU V. NGUYEN 1, JENNY M. KELLEY 2, SHUANG CAI 2, HONGEN ZHANG 2, JINGHUI ZHANG 1,4 , REBECCA WILSON 2, LAUREN MESSMER 2, YOUNG-HWA CHUNG 5, JEONG A. KIM 5, NEUNG HWA PARK 6, MYUNG-SOO LYU 6, IL HAN SONG 7, GEORGE KOMATSOULIS 1 and KENNETH H. BUETOW 1,2 1Center for Bioinformatics and Information Technology, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, U.S.A.; 2Laboratory of Population Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.; 3Basic Prevention Science Research Group, Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A; 4Department of Biotechnology/Computational Biology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, U.S.A.; 5Department of Internal Medicine, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea; 6Department of Internal Medicine, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, Ulsan, Korea; 7Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Dankook University, Cheon-An, Korea Abstract . We report on next-generation transcriptome Worldwide, liver cancer is the fifth most common cancer and sequencing results of three human hepatocellular carcinoma the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality (1). tumor/tumor-adjacent pairs. -

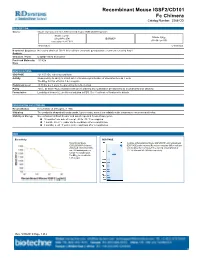

Recombinant Mouse IGSF2/CD101 Fc Chimera Catalog Number: 3368-CD

Recombinant Mouse IGSF2/CD101 Fc Chimera Catalog Number: 3368-CD DESCRIPTION Source Mouse myeloma cell line, NS0-derived mouse IGSF2/CD101 protein Mouse CD101 Mouse IgG (Gln21-Phe974) IEGRMDP 2a (Glu98-Lys330) Accession # A8E0Y8 N-terminus C-terminus N-terminal Sequence No results obtained. Gln21 inferred from enzymatic pyroglutamate treatment revealing Arg22. Analysis Structure / Form Disulfide-linked homodimer Predicted Molecular 133 kDa Mass SPECIFICATIONS SDS-PAGE 121-150 kDa, reducing conditions Activity Measured by its ability to inhibit anti-CD3-induced proliferation of stimulated human T cells. The ED50 for this effect is 1.4-8.4 μg/mL. Endotoxin Level <0.10 EU per 1 μg of the protein by the LAL method. Purity >95%, by SDS-PAGE visualized with Silver Staining and quantitative densitometry by Coomassie® Blue Staining. Formulation Lyophilized from a 0.2 μm filtered solution in PBS. See Certificate of Analysis for details. PREPARATION AND STORAGE Reconstitution Reconstitute at 400 μg/mL in PBS. Shipping The product is shipped with polar packs. Upon receipt, store it immediately at the temperature recommended below. Stability & Storage Use a manual defrost freezer and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. 12 months from date of receipt, -20 to -70 °C as supplied. 1 month, 2 to 8 °C under sterile conditions after reconstitution. 3 months, ≤ -20 °C under sterile conditions after reconstitution. DATA Bioactivity SDS-PAGE Recombinant Mouse 2 μg/lane of Recombinant Mouse IGSF2/CD101 was resolved with IGSF2/CD101 Fc Chimera SDS-PAGE under reducing (R) and non-reducing (NR) conditions (Catalog # 3368-CD) inhibits and visualized by Coomassie® Blue staining, showing bands at anti-CD3 antibody induced 121-150 kDa and 240-280 kDa, respectively. -

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association Between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic Asthma Ayoung Jeong 1,2, Medea Imboden 1,2, Akram Ghantous 3, Alexei Novoloaca 3, Anne-Elie Carsin 4,5,6, Manolis Kogevinas 4,5,6, Christian Schindler 1,2, Gianfranco Lovison 7, Zdenko Herceg 3, Cyrille Cuenin 3, Roel Vermeulen 8, Deborah Jarvis 9, André F. S. Amaral 9, Florian Kronenberg 10, Paolo Vineis 11,12 and Nicole Probst-Hensch 1,2,* 1 Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, 4051 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] (A.J.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 Department of Public Health, University of Basel, 4001 Basel, Switzerland 3 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 69372 Lyon, France; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (Z.H.); [email protected] (C.C.) 4 ISGlobal, Barcelona Institute for Global Health, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (A.-E.C.); [email protected] (M.K.) 5 Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08002 Barcelona, Spain 6 CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), 08005 Barcelona, Spain 7 Department of Economics, Business and Statistics, University of Palermo, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 8 Environmental Epidemiology Division, Utrecht University, Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, 3584CM Utrecht, Netherlands; [email protected] 9 Population Health and Occupational Disease, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, SW3 6LR London, UK; [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (A.F.S.A.) 10 Division of Genetic Epidemiology, Medical University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] 11 MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, W2 1PG London, UK; [email protected] 12 Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine (IIGM), 10126 Turin, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-61-284-8378 Int. -

Datasheet: MCA2236F Product Details

Datasheet: MCA2236F Description: MOUSE ANTI HUMAN CD101:FITC Specificity: CD101 Format: FITC Product Type: Monoclonal Antibody Clone: BB27 Isotype: IgG1 Quantity: 0.1 mg Product Details Applications This product has been reported to work in the following applications. This information is derived from testing within our laboratories, peer-reviewed publications or personal communications from the originators. Please refer to references indicated for further information. For general protocol recommendations, please visit www.bio-rad-antibodies.com/protocols. Yes No Not Determined Suggested Dilution Flow Cytometry 1/5 - 1/10 Where this antibody has not been tested for use in a particular technique this does not necessarily exclude its use in such procedures. Suggested working dilutions are given as a guide only. It is recommended that the user titrates the antibody for use their own system using appropriate negative/positive controls. Target Species Human Product Form Purified IgG conjugated to Fluorescein Isothiocyanate Isomer 1 (FITC) - liquid Max Ex/Em Fluorophore Excitation Max (nm) Emission Max (nm) FITC 490 525 Preparation Purified IgG prepared by affinity chromatography on Protein G from tissue culture supernatant Buffer Solution Phosphate buffered saline Preservative 0.09% Sodium Azide Stabilisers 1% Bovine Serum Albumin Approx. Protein IgG concentration 0.1 mg/ml Concentrations Immunogen Human thymic clone B12. External Database Links UniProt: Q93033 Related reagents Entrez Gene: Page 1 of 3 9398 CD101 Related reagents Synonyms EWI101, IGSF2, V7 Specificity Mouse anti Human CD101 antibody, clone BB27 recognizes human CD101, also known as Immunoglobulin superfamily member 2 (IgSF2), . Cell surface glycoprotein V7, Glu-Trp-Ile EWI motif-containing protein 101 or EWI-101. -

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 Bdbiosciences.Com/Cdmarkers

BD Biosciences Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 bdbiosciences.com/cdmarkers 23-12399-01 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD93 C1QR1,C1qRP, MXRA4, C1qR(P), Dj737e23.1, GR11 – – – – – + + – – + – CD220 Insulin receptor (INSR), IR Insulin, IGF-2 + + + + + + + + + Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), IGF-1R, type I IGF receptor (IGF-IR), CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD94 KLRD1, Kp43 HLA class I, NKG2-A, p39 + – + – – – – – – CD221 Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I), IGF-II, Insulin JTK13 + + + + + + + + + CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD178, FASLG, APO-1, FAS, TNFRSF6, CD95L, APT1LG1, APT1, FAS1, FASTM, CD95 CD178 (Fas ligand) + + + + + – – IGF-II, TGF-b latency-associated peptide (LAP), Proliferin, Prorenin, Plasminogen, ALPS1A, TNFSF6, FASL Cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6P-R, CIM6PR, CIMPR, CI- CD1d R3G1, R3 b-2-Microglobulin, MHC II CD222 Leukemia -

Chromosomal Instability and Copy Number Alterations in Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Thomas G

Human Cancer Biology Chromosomal Instability and Copy Number Alterations in Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Thomas G. Paulson,1,2 Carlo C. Maley,4,5 Xiaohong Li,2 Hongzhe Li,6 Carissa A. Sanchez,1,2 Dennis L. Chao,3 Robert D. Odze,7 Thomas L. Vaughan,2,8 Patricia L. Blount,1,2,10 and Brian J. Reid1,2,9,10 Abstract Purpose: Chromosomal instability, as assessed by many techniques, including DNA content aneuploidy, loss of heterozygosity, and comparative genomic hybridization, has consistently been reported to be common in cancer and rare in normal tissues. Recently, a panel of chromosome instability biomarkers, including loss of heterozygos- ity and DNA content, has been reported to identify patients at high and low risk of pro- gression from Barrett's esophagus (BE) to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EA), but required multiple platforms for implementation. Although chromosomal instability in- volving amplifications and deletions of chromosome regions have been observed in nearly all cancers, copy number alterations (CNA) in premalignant tissues have not been well characterized or evaluated in cohort studies as biomarkers of cancer risk. Experimental Design: We examined CNAs in 98 patients having either BE or EA using Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) array comparative genomic hybridization to char- acterize CNAs at different stages of progression ranging from early BE to advanced EA. Results: CNAs were rare in early stages (less than high-grade dysplasia) but were pro- gressively more frequent and larger in later stages (high-grade dysplasia and EA), in- cluding high-level amplifications. The number of CNAs correlated highly with DNA content aneuploidy.