Kenneth Gandar Dower by DJ Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6291/pennsylvania-county-histories-546291.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

f Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://arohive.org/details/pennsylvaniaooun18unse '/■ r. 1 . ■; * W:. ■. V / \ mm o A B B P^g^ B C • C D D E Page Page Page uv w w XYZ bird's-eive: vibw G VA ?es«rvoir NINEVEH From Nineveh to the Lake. .jl:^/SpUTH FORK .VIADUCT V„ fS.9 InaMSTowM. J*. Frorp per30i)al Sfcel'cb^s ai)d. Surveys of bl)p Ppipipsylvapia R. R., by perrpi^^iop. -A_XjEX. Y. XjEE, Architect and Civil Engineer, PITTSBURGH, PA. BRIDGE No.s'^'VgW “'■■^{Goncl - Viaduct Butlermill J.Unget^ SyAij'f By. Trump’* Caf-^ ^Carnp Cooemaugh rcTioN /O o ^ ^ ' ... ^!yup.^/««M4 •SANGTOLLOV^, COOPERSttAtc . Sonc ERl/ftANfJl, lAUGH \ Ru Ins of loundhouse/ Imohreulville CAMBRIA Cn 'sum iVl\ERHI LL Overhead Sridj^e Western Res^rvoi millviue Cambria -Iron Works 'J# H OW N A DAMS M:uKBoeK I No .15 SEVEim-1 WAITHSHED SOUTH FORK DAM PfTTSBURGH, p/ Copyright 1889 8v years back, caused u greater loss of life, ?Ttf ioHnsitowiv but the destructiou of property was slight in comparison with that of Johns¬ town and its vacinity. For eighteen hun¬ dred years Pompeii and Hevculancum have been favorite references as instances of unparalleled disasters in the annals (d the world; hut it was shown by an iirti- cle in the New Y’ork World, some days FRIDAY', JULY" 5, 1889. -

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Name,Year Foaled Sire Dam Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent I Broodmare 880 b. m. Provobay, 2000 Dynaformer Del Sovereign Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent II Broodmare prospect 1053 b. m. Cuff Me, 2007 Officer She'sgotgoldfever Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent III Yearling 1164 ch. c. unnamed, 2011 First Samurai Jill's Gem Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent IV Racing or broodmare prospect 1022 dk. b./br. f. Blue Catch, 2008 Flatter Nabbed Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent V Yearling 978 dk. b./br. c. unnamed, 2011 Old Fashioned With Hollandaise Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent VI Yearling 992 dk. b./br. c. First Defender, 2011 First Defence Altos de Chavon Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent VII Broodmare 890 gr/ro. m. Refrain, 1999 Unbridled's Song Inlaw Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent for Don Ameche III and Hayden Noriega Yearling 1014 ch. c. unnamed, 2011 Any Given Saturday Babeinthewoods Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent for Don Ameche III, Don Ameche Jr. and Prancing Horse Enterprise Yearling 1124 dk. b./br. c. unnamed, 2011 Harlan's Holiday Grandstone Barn 29 Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock LLC, Agent Racing or broodmare prospects 897 b. m. Rock Hard Baby, 2007 Rock Hard Ten Bully's Del Mar 916 b. f. Shesa Calendargirl, 2009 Pomeroy Memory Rock Barn 38 Consigned by Blackburn Farm (Michael T. Barnett), Agent Broodmares 873 b. m. Prado's Treasure, 2006 Yonaguska Madrid Lady 961 ch. -

Pursuit of the Spotted Lion Veteran Safari Guide, Farmer and Hunter, He Was Flying Had Given Gandar-Dower a Taste of Sceptical of Gandar-Dower’S Quarry

CONtENtS DrIvEN by DEvIlS - thE rEmarkablE StOry Of kC GaNDar-DOwEr 8 An eccentric adventurer comes to Kenya in search of the mythical spotted lions, known as Marozi, and ends up taking cheetahs to race on the track in England. SamUEl StEpkE - frOm SlavE tO prEaChEr part 2 13 Samuel Stepke feels like they’ve been abandoned when German missionaries are deported from Tanganyika in the 1920s and the young African pastors must lead the church. afrIkaNEr CONtrIbUtION tO kENya: rUGby, farmING aND SChOOlS 16 Eldoret Rugby Club dominates Kenyan rugby from the 1930s to the 1950s, led by characters like Stompie Jones. QUIrky rIDES aGaIN 20 Our intrepid young architect fnds that riding a horse in Karen during a thunderstorm is a real test of his skills. fOxhOUNDS IN SOtIk 26 Lt Colonel Reggie Walker starts a pack of foxhounds at Sotik after World War II and leads the hunt until Kenya’s independence. SwEDON GOES tO SChOOl at rIft vallEy aCaDEmy 30 A young Swedish boy fnds himself at a school in Kenya’s highlands. He chafes at the rules but is fascinated by the wildlife in the nearby forest and the valley below. maNy happy DayS I’vE SQUaNDErED part 14 35 As World War I winds down, Arthur Loveridge collects snakes, some of which escape into the camp. DEPARTMENTS Editorial 2 Sauti Zenu-Your Letters 4 Only in Africa 24 Book Reviews 38 History Quiz 40 Historic Photo Contest 41 History Mystery Contest 42 Old Africa Photo Album 44 Mwishowe 47 Cover Photo: Lt Colonel Reggie Walker founded a pack of foxhounds in Sotik in the 1940s and led the hunt until Kenya’s independence. -

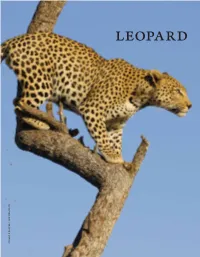

Leopard Stuart G Porter / Shutterstock G Porter Stuart נמר Leopard Namer

Leopard Stuart G Porter / Shutterstock G Porter Stuart נמר Leopard Namer The Leopards of Israel ִא ִּתי ִמ ְּל ָבנוֹן ַּכ ָּלה ִא ִּתי ִמ ְּל ָבנוֹן ָּת ִבוֹאי ָּתׁש ּוִרי ֵמרֹ ׁאש ֲא ָמ ָנה ֵמרֹ ׁאש NATURAL HISTORY ְׂש ִניר ְו ֶחְרמוֹן ִמ ְּמעֹנוֹת ֲאָריוֹת ֵמ ַהְרֵרי ְנ ֵמִרים׃ שיר השירים פרק ד The strikingly beautiful leopard is the most widespread of all the big cats. It lives in a variety of habitats in much of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. In former times, leop- be man-eaters in other parts of the world, and are hunted ards were abundant throughout Israel, especially in the as a result. In the first decade of the twentieth century, at hilly and mountainous regions: least five leopards were killed in between Jerusalem and Beit Shemesh; one of them badly mauled a person after With me from Lebanon, O bride, come with me from being shot.3 The last specimen was killed by a shepherd Lebanon, look from the peak of Amana, from the peak near Hanita in 1965.4 Another leopard subspecies that lived of Senir and Hermon, from the dens of lions, from the in the area was the Sinai leopard, Panthera pardus jarvus. It mountains of leopards. (Song. 4:8). was hunted by the Bedouin upon whose goats it preyed, The leopard of the mountains was the Anatolian leop- and is now extinct. ard, Panthera pardus tulliana, which was found in much of Today, the Arabian leopard, Panthera pardus nimr, is the hilly regions of Israel. After the 1834 Arab pogrom in the only subspecies of leopard to be found in Israel. -

C:\My Files\Meetings\2012 Winter Meeting\2012 Winter

THE INTERNATIONAL CAT ASSOCIATION, INC. 2012 Winter Board Meeting January 27-29, 2012 Harlingen, Texas Open Session - 8:15AM-Noon January 27, 2012, Friday, 8:15AM ACTION TIME PAGE Welcome and Call to Order Fisher Verbal 8:15-8:30AM 1. Roll Call Fisher Verbal - 2. Welcome Board Fisher Verbal - Consent Agenda 8:30-8:40AM 1. Future Annuals, Semi-Annuals EO Accept .................... 4 2. Minutes, Corrections/Additions EO Approve - Governance 8:40-11AM 1. President’s Report Fisher Inform .......................- 2. Follow Up Report All Discuss ..................... 5 3. Eligibility to vote for breed committees Fisher Discuss - 4. Report of Re-alignment Committee Wood Approve .................... 6 Break - 10-10:15AM Fiduciary 11- 011:30AM 1. FY2011 Audit Report EO Accept .................... 11 2. Budget Report First Six Months EO to be furnished ................. 3. Set Winter Meeting Reimbursements BOD Approve - Administrative 11:30-Noon 1. IWRW on Certificates Basquine Discuss - 2. Adding Judges Information to TREND Fisher Discuss - Lunch: NOON - 1:30PM Administrative (continued) 1:30-2:30PM 3. Report on Voting Lesley Hart Discuss - 4. Status of Online Projects Larry Hart Discuss - 5. Report of Ad Hoc Committee-Clubs Susan ............................... 27 Executive Session 2:30-5:30PM 2012 Winter Meeting Executive Agenda, Page 1 January 28, 2012, Friday, 8:15AM ACTION TIME PAGE Executive Session 8:30AM-NOON Executive Session continues Lunch: NOON - 1:30PM Executive Session - Business Planning concludes Break - 1:30-3:15PM Open Session: 3:15-5:30PM PROPOSALS Standing Rules 3:15-4PM 1. 105.4.3 Breed Committee Parkinson Approve ...................... 28 2. 209.1.1.4 Marked Catalogs Farley Approve ..................... -

Computing Text Semantic Relatedness Using the Contents and Links of a Hypertext Encyclopedia

Computing Text Semantic Relatedness using the Contents and Links of a Hypertext Encyclopedia Majid Yazdania,b, Andrei Popescu-Belisa aIdiap Research Institute 1920 Martigny, Switzerland bEPFL, Ecole´ Polytechnique Fed´ erale´ de Lausanne 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Abstract We propose a method for computing semantic relatedness between words or texts by using knowledge from hypertext encyclopedias such as Wikipedia. A network of concepts is built by filtering the encyclopedia’s articles, each concept corresponding to an article. Two types of weighted links between concepts are considered: one based on hyperlinks between the texts of the articles, and another one based on the lexical similarity between them. We propose and imple- ment an efficient random walk algorithm that computes the distance between nodes, and then between sets of nodes, using the visiting probability from one (set of) node(s) to another. Moreover, to make the algorithm tractable, we propose and validate empirically two truncation methods, and then use an embedding space to learn an approximation of visiting probability. To evaluate the proposed distance, we apply our method to four important tasks in natural language processing: word similarity, document similarity, document clustering and classification, and ranking in in- formation retrieval. The performance of the method is state-of-the-art or close to it for each task, thus demonstrating the generality of the knowledge resource. Moreover, using both hyperlinks and lexical similarity links improves the scores with respect to a method using only one of them, because hyperlinks bring additional real-world knowledge not captured by lexical similarity. Keywords: Text semantic relatedness, Distance metric learning, Learning to rank, Random walk, Text classification, Text similarity, Document clustering, Information retrieval, Word similarity 1. -

Animal Kingdom

THE TORAH ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE ANIMAL KINGDOM Volume I: Wild Animals/ Chayos Sample Chapter: The Leopard RABBI NATAN SLIFKIN The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdomis a milestone in Jewish publish- ing. Complete with stunning, full-color photographs, the final work will span four volumes. The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom includes: • Entries on every mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian, insect and fish found in the Torah, Prophets and Writings; • All scriptural citations, and a vast range of sources from the Talmud and Midrash; • Detailed analyses of the identities of these animals, based on classical Jewish sources and contemporary zoology; • The symbolism of these animals in Jewish thought throughout the ages; • Zoological information about these animals and fascinating facts; • Studies of man’s relationship with animals in Torah philosophy and law; • Lessons that Judaism derives from the animal kingdom for us to use in our own daily lives; • Laws relating to the various different animals. The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom is an essential reference work that will one day be commonplace in every home and educational institution. For more details, and to download this chapter, see www.zootorah.com/encyclopedia. Rabbi Natan Slifkin, the internationally renowned “Zoo Rabbi,” is a popular lec- turer and the author of numerous works on the topic of Judaism and the natural sciences. He has been passionately study- ing the animal kingdom his entire life, and began working on The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom over a decade ago. © Natan Slifkin 2011. This sample chapter may be freely distributed provided it is kept com- plete and intact. -

Mystery Cats of the World Revisited: Blue Tigers, King Cheetahs, Black Cougars, Spotted Lions, and More by Karl P

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 433–443, 2021 0892-3310/21 BOOK REVIEW Mystery Cats of the World Revisited: Blue Tigers, King Cheetahs, Black Cougars, Spotted Lions, and More by Karl P. N. Shuker. Anomalist Books, 2020. 397 + xv pp. $24.95 (paperback). ISBN 978-1-949501-17-9. Reviewed by George M. Eberhart Chicago, Illinois https://10.31275/20212011 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC At long last, after 31 years, the first book by noted British zoologist and cryptozoologist Karl Shuker has been expanded and updated. Mystery Cats of the World first appeared in 1989 and was the only book to review feline cryptids worldwide. In this 2020 edition, Shuker repeats this admirable achievement, and in the process gives us a solid overview of current knowledge of felid evolution, taxonomy, and genetic variation. In fact, the only feline mystery cat he does not describe is Hello Kitty. This edition will leave you purring with cryptozoological delight. Shuker has more than kept up with cryptozoology over the years, keeping the public informed with numerous popular books on dragons, new and rediscovered animals, the Loch Ness monster, and many other lesser-known cryptids. His ShukerNature blog (2009 to present) and his regular “Alien Zoo” column in Fortean Times provide an always- fascinating glimpse into ongoing cryptozoological controversies. Scientific names and genetic relationships are updated through- out the text in this new edition. He notes that since 1989, our under- standing of genes that cause variations in felid coat color has become more complicated. For example, the chinchilla mutation in tyrosinase was then considered responsible for “partial albino” tigers (white tigers with black stripes). -

Journal of Scientific Exploration

Journal of Scientific Exploration Journal of Journal A Publication of the volume 35 issue 2 Scientific Exploration Summer 2021 Summer 2021 2021 Summer pp. 257–472 JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC EXPLORATION A Publication of the Society for Scientific Exploration (ISSN 0892-3310) published quarterly, and continuously since 1987 Editorial Office: [email protected] Manuscript Submission: http://journalofscientificexploration.org/index.php/jse/ Editor-in-Chief: Stephen E. Braude, University of Maryland Baltimore County Managing Editor: Kathleen E. Erickson, San Jose State University, California Assistant Managing Editor: Elissa Hoeger, Princeton, New Jersey Associate Editors Peter A. Bancel, Institut Métapsychique International, Paris, France; Institute of Noetic Sciences, Petaluma, California, USA Imants Barušs, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada Robert Bobrow, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York, USA Jeremy Drake, Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA Hartmut Grote, Cardiff University, United Kingdom Julia Mossbridge, University of San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA Roger D. Nelson, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA Mark Rodeghier, Center for UFO Studies, Chicago, Illinois, USA Paul H. Smith, Remote Viewing Instructional Services, Cedar City, Utah, USA Harald Walach, Viadrina European University, Frankfurt in Brandenburg, Germany Publications Committee Chair: Garret Moddel, University of Colorado Boulder Editorial Board Dr. Mikel Aickin, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ Dr. Steven J. Dick, U.S. Naval Observatory, Washington, DC Dr. Peter Fenwick, Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK Dr. Alan Gauld, University of Nottingham, UK Prof. W. H. Jefferys, University of Texas, Austin, TX Dr. Wayne B. Jonas, Samueli Institute, Alexandria, VA Dr. Michael Levin, Tufts University, Boston, MA Dr. David C. -

Fiche De Totem : Marozi

Fiche de totem : Marozi Le marozi est un lion vivant sur les hauts plateaux d'Afrique principalement au Kenya.Il possède un pelage tacheté variant du jaune au brun,il est plus petit que le lion afriquain.Contrairement aux autres lion le mâle chasse avec les femelles.Le male possède une courte crinière.C'est un carnassier il se nourrit principalement de buffle et d'antilope. Le marozi ou lion tacheté du Kenya est un animal très mystérieux : son existence est encore mise en doute, il a d'ailleurs été très peu observé, c'est pourquoi il est difficile de lui attribuer un comportement particulier. Cependant, s'il est un hybride comme certains le disent, son caractère est très imprévisible puisqu'il aurait hérité de celui de deux espèces différentes : il oscillerait entre le caractère grégaire du lion et le tempérament solitaire et territorial du Floches léopard. Extérieur : Brun foncé Intérieur : Jaune Parmi les hypothèses de l'existence du marozi, on parle aussi d'une sous-espèce particulière de lion, adaptée à un milieu de montagnes. Cela expliquerait son apparence de lion de petite taille, avec une empreinte de patte est Classification proche de celle du lion elle aussi, bien que plus petite. Sous-Embranchement : Vertebrata Malgré le mystère qui entoure cette espèce, le marozi et le lion sont clairement Classe : Mammalia distingués par les peuples africains. Les Kikuyu, par exemple, désignent par Ordre : Carnivora simba le lion des plaines et par marozi le lion tacheté du Kenya. -

Biggest New Animal Discoveries of 2013

26/12/13 Frontiers of Zoology: Biggest new animal discoveries of 2013 Compartilhar 0 mais Próximo blog» FRONTIERS OF ZOOLOGY Dale A. Drinnon has been a researcher in the field of Cryptozoology for the past 30+ years and has corresponded with Bernard Heuvelmans and Ivan T. Sanderson. He has a degree in Anthropology from Indiana University and is a freelance artist and writer. Motto: "I would rather be right and entirely alone than wrong in the company with all the rest of the world"--Ambroise Pare', "the father of modern surgery", in his refutation of fake unicorn horns. Member of The Crypto Crew: http://www.thecryptocrew.com/ Please Also Visit our Sister Blog, Frontiers of Anthropology: http://frontiers-of-anthropology.blogspot.com/ And the new group for trying out fictional projects (Includes Cryptofiction Projects): http://cedar-and-willow.blogspot.com/ And Kyle Germann's Blog http://www.demonhunterscompendium.blogspot.com/ And Jay's Blog, Bizarre Zoology http://bizarrezoology.blogspot.com/ Tuesday, 24 December 2013 Follow ers Biggest new animal discoveries of 2013 Join this site w ith Google Friend Connect Biggest new animal discoveries of 2013 (photos) Members (146) More » Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com December 23, 2013 http://news.mongabay.com/2013/1223-top-new-species-2013.html Thousands of species were scientifically described for the first time in 2013. Many of these were "cryptic species" that were identified after genetic analysis distinguished them from closely- related species, while others were totally novel. Below are some of the most interesting "new species" discoveries that took place or were formally announced in 2013.