Photosynthetic Rate, Flowering, and Yield Component Alteration in Hazelnut in Response to Different Light Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filbert European Corylus Avellana Corylus Avellana Commonly Called

Filbert European Corylus avellana Corylus avellana commonly called European Filbert, European hazel, cobnut and Harry Lauder’s walking stick is a deciduous, thicket-forming, multi-trunked suckering shrub. Common names of filbert and hazel are likely interchangeable. Hazel is more often used in reference to wild specimens and filbert is more likely to be used in reference to cultivated plants. The filbert nuts to be produced in commerce primarily come from plants (C. avellano x C. maxima). ‘Contorta’, commonly called contorted filbert, corkscrew hazel or Harry Lauder’s Walking Stick, is contorted version of the species plant. It was discovered growing as a sport in an English hedgerow In the mid-1800s by Victorian Gardner Cannon Ellacombe. This plant was given the common name of Harry Lauder’s walking stick in the 1900s in honor of the Scottish entertainer Harry Lauder. The European Filbert leaves are dark green, slightly covered with fine soft hairs above and beneath; alternate; 2-4” in length, somewhat circular to egg – shaped or heart – shaped, abruptly tapers to a point at apex, edge doubly toothed, often with lobes, petiole ¼” to ½” long. The twigs are brown, glandular – hairy. Buds green to brown, hairless with hairy scale; overlapping, egg shaped to round. Flowers/Fruit: Flowers monoecious; male flowers are large (2”to 3”) catkins, yellow – brown, late winter to early spring blooming; female flowers inconspicuous. Fruit a nut; nuts inside involucre, which is toothed or lubed and nearly the length of the nut; ¾” in length; edible fruit grown commercially as a crop. European Filbert bark is pale to gray – brown, smoother with age, not an ornamental feature. -

Nutritive Value and Degradability of Leaves from Temperate Woody Resources for Feeding Ruminants in Summer

3rd European Agroforestry Conference Montpellier, 23-25 May 2016 Silvopastoralism (poster) NUTRITIVE VALUE AND DEGRADABILITY OF LEAVES FROM TEMPERATE WOODY RESOURCES FOR FEEDING RUMINANTS IN SUMMER Emile JC 1*, Delagarde R 2, Barre P 3, Novak S 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] mailto:(1) INRA, UE 1373 FERLUS, 86600 Lusignan, France (2) INRA, UMR 1348 INRA-Agrocampus Ouest, 35590 Saint-Gilles, France (3) INRA, UR 4 URP3F, 86600 Lusignan, France 1/ Introduction Integrating agroforestry in livestock farming systems may be a real opportunity in the current climatic, social and economic conditions. Trees can contribute to improve welfare of grazing ruminants. The production of leaves from woody plants may also constitute a forage resource for livestock (Papanastasis et al. 2008) during periods of low grasslands production (summer and autumn). To know the potential of leaves from woody plants to be fed by ruminants, including dairy females, the nutritive value of these new forages has to be evaluated. References on nutritive values that already exist for woody plants come mainly from tropical or Mediterranean climatic conditions (http://www.feedipedia.org/) and very few data are currently available for the temperate regions. In the frame of a long term mixed crop-dairy system experiment integrating agroforestry (Novak et al. 2016), a large evaluation of leaves from woody resources has been initiated. The objective of this evaluation is to characterise leaves of woody forage resources potentially available for ruminants (hedgerows, coppices, shrubs, pollarded trees), either directly by browsing or fed after cutting. This paper presents the evaluation of a first set of 12 woody resources for which the feeding value is evaluated through their protein and fibre concentrations, in vitro digestibility (enzymatic method) and effective ruminal degradability. -

Descriptors for Hazelnut (Corylus Avellana L.)

Descriptors for Hazelnut(Corylus avellana L.) List of Descriptors Allium (E, S) 2001 Pearl millet (E/F) 1993 Almond (revised)* (E) 1985 Pepino (E) 2004 Apple* (E) 1982 Phaseolus acutifolius (E) 1985 Apricot* (E) 1984 Phaseolus coccineus* (E) 1983 Avocado (E/S) 1995 Phaseolus lunatus (P) 2001 Bambara groundnut (E, F) 2000 Phaseolus vulgaris* (E, P) 1982 Banana (E, S, F) 1996 Pigeonpea (E) 1993 Barley (E) 1994 Pineapple (E) 1991 Beta (E) 1991 Pistachio (A, R, E, F) 1997 Black pepper (E/S) 1995 Pistacia (excluding Pistacia vera) (E) 1998 Brassica and Raphanus (E) 1990 Plum* (E) 1985 Brassica campestris L. (E) 1987 Potato variety* (E) 1985 Buckwheat (E) 1994 Quinua* (E) 1981 Cañahua (S) 2005 Rambutan 2003 Capsicum (E/S) 1995 Rice* (E) 2007 Cardamom (E) 1994 Rocket (E, I) 1999 Carrot (E, S, F) 1998 Rye and Triticale* (E) 1985 Cashew* (E) 1986 Safflower* (E) 1983 Cherry* (E) 1985 Sesame (E) 2004 Chickpea (E) 1993 Setaria italica and S. pumilia (E) 1985 Citrus (E, F, S) 1999 Shea tree (E) 2006 Coconut (E) 1995 Sorghum (E/F) 1993 Coffee (E, S, F) 1996 Soyabean* (E/C) 1984 Cotton (revised)* (E) 1985 Strawberry (E) 1986 Cowpea (E, P)* 1983 Sunflower* (E) 1985 Cultivated potato* (E) 1977 Sweet potato (E/S/F) 1991 Date Palm (F) 2005 Taro (E, F, S) 1999 Durian (E) 2007 Tea (E, S, F) 1997 Echinochloa millet* (E) 1983 Tomato (E, S, F) 1996 Eggplant (E/F) 1990 Tropical fruit (revised)* (E) 1980 Faba bean* (E) 1985 Ulluco (S) 2003 Fig (E) 2003 Vigna aconitifolia and V. -

Effects of Processing Treatments on Nutritional Quality of Raw Almond (Terminalia Catappa Linn.) Kernels

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2016, 7(1):1-7 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Effects of processing treatments on nutritional quality of raw almond (Terminalia catappa Linn.) kernels *Makinde Folasade M. and Oladunni Subomi S. Department of Food Science and Technology, Bowen University, Iwo, Osun State, Nigeria _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Almond (Terminalia catappa Linn) is one of the lesser utilized oil kernel distributed throughout the tropics including Nigeria ecosystem. In this research work, the effects of soaking, blanching, autoclaving and roasting on the proximate, mineral, vitamin and anti-nutritional concentrations of almond kernel were determined. The result of chemical composition revealed that raw almond kernel contained 11.93% moisture, 23.0% crude protein, 48.1% crude fat, 2.43% crude fiber, 2.69% ash, 12.0% carbohydrate, 0.35mg/100g thiamine, 0.15mg/100g riboflavin, 0.19mg/100g niacin and minerals among which the most important are potassium (9.87 mg/100g), calcium (4.66 mg/100g) and magnesium (4.45 mg/100g). Tannin, phytate and oxalate concentration in raw almond kernel were 0.15, 0.13 and 0.15mg/100g respectively. Increase in ash and fiber was noted for treated samples with time compared to raw almond. Compared to untreated kernels, soaking, blanching and autoclaving decreased fat content but there was increase during roasting of the kernels. Mineral concentrations were significantly increased by various treatments compared to raw kernel. However, roasting for 15 min resulted in highest increase in potassium (41.2 percent), calcium (45.1 percent), phosphorus (43.3 percent) and magnesium (43.6 percent). -

Hazelnuts Resistant to Eastern Filbert Blight: Are We There Yet?

Hazelnuts Resistant to Eastern Filbert Blight: Are We There Yet? Thomas J. Molnar, Ph.D. Plant Biology and Pathology Dept. Rutgers University The American Chestnut Society Annual Meeting October 22, 2011 Nut Tree Breeding at Rutgers Based on the tremendous genetic improvements demonstrated in several previously underutilized turf species, Dr. C. Reed Funk strongly believed similar work could be done with nut trees Title of project started in 1996: Underutilized Perennial Food Crops Genetic Improvement Tom Molnar and Reed Funk Program Adelphia Research Farm August 2001 Nut Breeding at Rutgers Starting in 1996, species of interest included – black walnuts, Persian walnuts and heartnuts – pecans, hickories Pecan shade trial – chestnuts, Adelphia 2000 – almonds, – hazelnuts We built a germplasm collection of over 25,000 trees planted across five Rutgers research farms – Cream Ridge Fruit Research Farm (Cream Ridge, NJ) – Adelphia Research Farm (Freehold, NJ) Pecan shade trial Adelphia 2008 – HF1, HF2, HF3 (North Brunswick, NJ) Nut Breeding at Rutgers Goals – Identify species that show the greatest potential for New Jersey and Mid- Atlantic region – Develop breeding program to create superior well- adapted cultivars that reliably produce high- quality, high-value crops • while requiring reduced inputs of pesticides, fungicides, management, etc. Nut Breeding at Rutgers While most species showed great promise for substantial improvement, we had to narrow our focus to be most effective Hazelnuts stood out as the species where we could make significant contributions in a relatively short period of time – Major focus since 2000 Hazelnuts at Rutgers Why we chose to focus on hazelnuts: – success of initial plantings made in 1996/1997 with few pests and diseases – short generation time and small plant size (4 years from seed to seed) – wide genetic diversity and the ability to hybridize different species – ease of making controlled crosses – backlog of information and breeding advances – existing technologies and markets for nuts Hazelnuts: Corylus spp. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached Copy Is Furnished to the Author for Internal Non-Commerci

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/authorsrights Author's personal copy Scientia Horticulturae 171 (2014) 91–94 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Scientia Horticulturae journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scihorti Short communication Effect of coconut water and growth regulator supplements on in vitro propagation of Corylus avellana L ∗ M.A. Sandoval Prando, P. Chiavazza, A. Faggio, C. Contessa Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie Forestali e Alimentari (DISAFA), Università degli Studi di Torino, Largo Paolo Braccini, 2-10095 Grugliasco, TO, Italy a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Corylus avellana L. represents an economically important crop in the European Union. Several protocols of Received 3 February 2014 hazelnut micropropagation have been tested but have not yet provided effective methods to allow large- Received in revised form 27 March 2014 scale propagation for commercial purposes, due to poor proliferation and yield. The aim of this work Accepted 31 March 2014 was to study the in vitro effects of coconut water (CW) in combinations with gibberellins and cytokinins Available online 19 April 2014 on proliferation and growth of hazelnut in vitro and the effect of explants orientation on shoot growth. -

Juglandaceae (Walnuts)

A start for archaeological Nutters: some edible nuts for archaeologists. By Dorian Q Fuller 24.10.2007 Institute of Archaeology, University College London A “nut” is an edible hard seed, which occurs as a single seed contained in a tough or fibrous pericarp or endocarp. But there are numerous kinds of “nuts” to do not behave according to this anatomical definition (see “nut-alikes” below). Only some major categories of nuts will be treated here, by taxonomic family, selected due to there ethnographic importance or archaeological visibility. Species lists below are not comprehensive but representative of the continental distribution of useful taxa. Nuts are seasonally abundant (autumn/post-monsoon) and readily storable. Some good starting points: E. A. Menninger (1977) Edible Nuts of the World. Horticultural Books, Stuart, Fl.; F. Reosengarten, Jr. (1984) The Book of Edible Nuts. Walker New York) Trapaceae (water chestnuts) Note on terminological confusion with “Chinese waterchestnuts” which are actually sedge rhizome tubers (Eleocharis dulcis) Trapa natans European water chestnut Trapa bispinosa East Asia, Neolithic China (Hemudu) Trapa bicornis Southeast Asia and South Asia Trapa japonica Japan, jomon sites Anacardiaceae Includes Piastchios, also mangos (South & Southeast Asia), cashews (South America), and numerous poisonous tropical nuts. Pistacia vera true pistachio of commerce Pistacia atlantica Euphorbiaceae This family includes castor oil plant (Ricinus communis), rubber (Hevea), cassava (Manihot esculenta), the emblic myrobalan fruit (of India & SE Asia), Phyllanthus emblica, and at least important nut groups: Aleurites spp. Candlenuts, food and candlenut oil (SE Asia, Pacific) Archaeological record: Late Pleistocene Timor, Early Holocene reports from New Guinea, New Ireland, Bismarcks; Spirit Cave, Thailand (Early Holocene) (Yen 1979; Latinis 2000) Rincinodendron rautanenii the mongongo nut, a Dobe !Kung staple (S. -

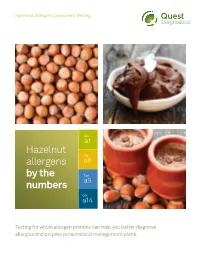

Hazelnut Allergens by the Numbers

Hazelnut allergen component testing Cor a1 Hazelnut Cor allergens a8 by the Cor numbers a9 Cor a14 Testing for whole allergen proteins can help you better diagnose allergies and prepare personalized management plans. High levels of hazelnut IgE can predict the likelihood of hazelnut sensitivity, but may not be solely predictive of reactions or allergic response.1 Hazelnut allergen component testing Measurement of specific IgE by blood Allergen components, in conjunction test that provides objective assessment with whole-allergen test results, help of sensitization to hazelnut is only the you better diagnose allergies, allowing first step in discovering the likelihood of you to prepare more comprehensive a systemic reaction and the necessary management plans. precautions that may be prescribed. Hazelnut allergen component test results can help determine which specific proteins your patient is sensitized to. Cor Cor Cor a1 a8 a9 Cor a14 LOWER RISK of VARIABLE RISK HIGHER RISK systemic reaction associated with local of systemic reaction primarily associated and systematic reactions including anaphylaxis1,2,8,9 2 2,5,6 with local reactions including anaphylaxis • Heat and digestion stabile10 3 7 • Heat and digestion labile • Heat and digestion stabile • Sensitization to these can • Cross-reactive with • Indicates cross-reactivity, appear early in life and indicates pollens (e.g., birch)1,4 often from a primary peach a primary hazelnut allergy1 sensitization5 Take the diagnosis and management of hazelnut-sensitized patients to a whole new level. RISK ASSESSMENT TEST INTERPRETATIONS AND NEXT STEPS IgE antibodies for Indication Patient Suggestions Test for sensitization to a14 Cor a14 Associated with systemic peanuts and other tree nuts and/or reactions in hazelnut- (e.g., walnuts and Brazil 1,2,8,9 Cor a9 sensitized patients. -

The Expansion of Hazel (Corylus Avellana L.) in the Southern Alps: a Key for Understanding Its Early Holocene History in Europe?

ARTICLE IN PRESS Quaternary Science Reviews 25 (2006) 612–631 The expansion of hazel (Corylus avellana L.) in the southern Alps: a key for understanding its early Holocene history in Europe? Walter Finsingera,b,Ã, Willy Tinnera, W.O. van der Knaapa, Brigitta Ammanna aInstitute of Plant Sciences Universita¨t Bern, Altenbergrain 21, CH– 3013 Bern, Switzerland bDipartimento di Biologia Vegetale, Universita` di Roma ‘‘La Sapienza’’, P.le Aldo Moro 5, I– 00185 Roma, Italy Received 8 October 2004; accepted 17 May 2005 Abstract In Northwestern and Central Europe the Holocene expansion of Corylus occurred before or at the same time as that of other thermophilous trees (e.g. Quercus). This sequence of expansion has been explained by migrational lag, competition, climatic changes, human assistance, or disturbance by fire. In the southern Alps, however, hazel expanded around 10,500 cal yr BP, more than two millennia after oak had become important. This delayed expansion is in contrast with the rapid expansion often assumed for hazel in central Northern Europe. We use two well-dated pollen and charcoal records from the southern forelands of the Alps: Lago Piccolo di Avigliana and Lago di Origlio. We conclude that distance of refugia, speed of seed dispersal, and competition cannot sufficiently explain the absence of the hazel expansion prior to the establishment of mixed oak forests in the southern Alps. Instead our records indicate that higher moisture availability and low temperatures inhibited hazel and favoured the establishment of pine and mixed oak forests during the Allerød. The expansion of hazel 11,000–10,500 cal yr BP was favoured by a combination of high seasonality, summer drought and frequent fires, which helped hazel to out-compete oak in the south as well as north of the Alps. -

Corylus Americana, American Hazelnut

Of interest this week at Beal... American Hazelnut Corylus americana Family: the Birch family, Betulaceae Also called American filbert W. J. Beal This nut-bearing member of the birch family is not as well known as its commercial Botanical Garden European counterpart, Corylus avellana. Ours are located on the hill overlooking the north side of the pond. Just as the European filbert has a long history of use in Europe, the American hazelnut has a long history of being harvested for food by the Indigenous First Nations peoples of Eastern North America. The fruit of the American hazelnut is comparable to the fruit of the cultivated European hazelnut, except significantly smaller. American hazelnut ranges from Maine west to Saskatchewan, south to eastern Oklahoma, east to northern Florida. In Michigan, American hazelnut is common throughout the southerly counties of the Lower Peninsula, but at the approximate latitude of the town of Clare, it is replaced by the more northerly distribution of beaked hazelnut, Corylus cornuta. American hazelnut flowers a few days after temperatures are consistently above 40 degrees. Male flowers are catkins that expand upon opening to release massive quantities of pollen. The unexpanded male catkins comprise one of its most recognizable winter features. Female flowers are striking but tiny sprays of bright red stigmata up to three millimeters in length. Flowers of both sexes are born on the same stems. American hazelnut forms thickets some 6-10 feet (2-3.3 m) in height especially along forest trails and edges. After pollination, the female flowers expand and wrap themselves in large frilly bracts that are the hallmark of their presence. -

Test Instruction of Them Are Very Heat Resistant Making Them Stable to Different Production Processes

General Information Hazelnut (Corylus avellana) belongs to the birch plants. With 13 % the fraction of proteins in hazel- nuts is high. Many of these proteins are known for being allergenic, such as Cor a 9 and Cor a 11. Most Test Instruction of them are very heat resistant making them stable to different production processes. For this reason Hazelnut hazelnut represents an important food allergen. For hazelnut allergic persons hidden hazelnut allergens 96/48 Tests in food are a critical problem. Already very low amounts of hazelnuts can cause allergic reactions, which may lead to anaphylactic shock in severe Enzyme Immunoassay cases. Because of this, hazelnut allergic persons for the Quantitative must strictly avoid the consumption of hazelnuts or Determination of hazelnut containing food. Crosscontamination, most- Hazelnut in Food ly in consequence of the production process is often noticed. The chocolate production process is a representative example. This explains why in many Cat.-No.: HU0030010 cases the existence of hazelnut residues in foods cannot be excluded. For this reason sensitive Version: September 25th, 2017 detection systems for hazelnut residues in foodstuffs are required. This document represents a combined test The SENSISpec Hazelnut ELISA represents a highly instruction for the products HU0030010 (96 sensitive detection system and is particularly cap- well) and HU0030034 (48 well). able of the quantification of hazelnut residues in cookies, cereals, ice cream and chocolate. Principle of the Test The SENSISpec Hazelnut quantitative test is based on the principle of the enzyme linked immunosorbent assay. An antibody directed against hazelnut prote- ins is bound on the surface of a microtiter plate. -

Identifying and Evaluating Eastern Filbert Blight Resistant

IDENTIFYING AND EVALUATING EASTERN FILBERT BLIGHT RESISTANT HAZELNUTS (CORYLUS SPP.) IN NEW JERSEY By JOHN MICHAEL CAPIK A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Graduate Program in Plant Biology written under the direction of Dr. Thomas J. Molnar and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Identifying and Evaluating Eastern Filbert Blight Resistant Hazelnuts (Corylus spp.) in New Jersey by JOHN MICHAEL CAPIK Thesis Director: Dr. Thomas J. Molnar Eastern filbert blight (EFB), caused by the fungus Anisogramma anomala (Peck) E. Müller, is a destructive disease of European hazelnut (Corylus avellana). While the wild North American hazelnut, C. americana, only experiences minor symptoms, commercially grown C. avellana is extremely susceptible. Anisogramma anomala, whose range includes much of the U.S. east of the Rocky Mountains, is considered to be the main impediment to commercial hazelnut production in the East. As such, identifying and developing resistant C. avellana germplasm is critical to establishing an industry in this region. To support this goal, several research projects were undertaken. In the first study, 193 clonal hazelnut accessions spanning multiple Corylus species and inter-specific hybrids were examined for their disease response to EFB in New Jersey. In summary, despite the fact that many of the plants were shown to be resistant in Oregon, some accessions developed EFB in New Jersey. These results support previous work that suggests different isolates of the pathogen are present in the eastern U.S., and resistance may not hold up unilaterally.