Timbre As Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY . It seems, however, far more likely that Chopin Notes on the musical text 3 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were intended a different grouping for this figure, e.g.: 7 added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation or . See the Source Commentary. are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an 3 inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, Bar 84 A gentle change of pedal is indicated on the final crotchet pedal indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in order to avoid the clash of g -f. in round brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all the markings in brackets. 2a & 2b. Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9 No. 2 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, (versions with variants) 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small italic numerals , 1 2 3 4 5 . Wherever authentic fingering is enclosed in The sources indicate that while both performing the Nocturne parentheses this means that it was not present in the primary sources, and working on it with pupils, Chopin was introducing more or but added by Chopin to his pupils' copies. -

Timbre in Musical and Vocal Sounds: the Link to Shared

TIMBRE IN MUSICAL AND VOCAL SOUNDS: THE LINK TO SHARED EMOTION PROCESSING MECHANISMS A Dissertation by CASADY DIANE BOWMAN Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Takashi Yamauchi Committee Members, Jyotsna Vaid Jayson Beaster-Jones Thomas Ferris Head of Department, Douglass Woods December 2015 Major Subject: Psychology Copyright 2015 Casady Diane Bowman ABSTRACT Music and speech are used to express emotion, yet it is unclear how these domains are related. This dissertation addresses three problems in the current literature. First, speech and music have largely been studied separately. Second, studies in these domains are primarily correlational. Third, most studies utilize dimensional emotions where motivational salience has not been considered. A three-part regression study investigated the first problem, and examined whether acoustic components explained emotion in instrumental (Experiment 1a), baby (Experiment 1b), and artificial mechanical sounds (Experiment 1c). Participants rated whether stimuli sounded happy, sad, angry, fearful and disgusting. Eight acoustic components were extracted from the sounds and a regression analysis revealed that the components explained participants’ emotion ratings of instrumental and baby sounds well, but not artificial mechanical sounds. These results indicate that instrumental and baby sounds were perceived similarly compared to artificial mechanical sounds. To address the second and third problems, I examined the extent to which emotion processing for vocal and instrumental sounds crossed domains and whether similar mechanisms were used for emotion perception. In two sets of four-part experiments participants heard an angry or fearful sound four times, followed by a test sound from an anger-fear morphed continuum and judged whether the test sound was angry or fearful. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

Williams Percussion Ensemble Noise/Signal

Williams Percussion Ensemble Noise/Signal We call “noise” any undesirable signal in the transmission of a message through a channel, and we use this term for all types of perturbation, whether the message is sonic or visual. Thus shocks, crackling, and atmospherics are noises in radio transmission. A white or black spot on a television screen, a gray fog, some dashes not belonging to the transmitted message, a spot of ink on a newspaper, a tear in a page of a book, a colored spot on a picture are “noises” in visual messages. A rumor without foundation is a “noise” in a sociological message. At first sight, it may seem that the distinction between “noise” and “signal” is easily made on the basis of the distinction between order and disorder. A signal appears to be essentially an ordered phenomenon while crackling, or atmospherics, are disordered phenomena, formless blotches on a structured picture of sound. However, there is no absolute structural difference between noise and signal. They are of the same nature. The only difference which can be logically established between them is based exclusively on the concept of intent on the part of the transmitter: A noise is a signal that the sender does not want to transmit. Or, more generally: A noise is a sound we do not want to hear. — Abraham Moles, from Information Theory and Esthetic Perception In the ordered world of Western art music, percussion has long been employed to bring in the noise. The bulk of the percussion family is in fact comprised of instruments that produce noise rather than tone. -

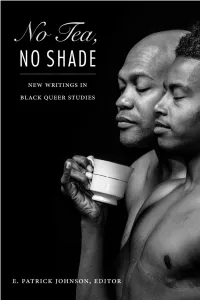

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

Some Preliminary Thoughts on Chiyoko Szlavnics' Music

Some Preliminary Thoughts on Chiyoko Szlavnics’ Music Makis Solomos To cite this version: Makis Solomos. Some Preliminary Thoughts on Chiyoko Szlavnics’ Music. Πoλυϕωνια, Athens, 2015. hal-01202895 HAL Id: hal-01202895 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01202895 Submitted on 21 Sep 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Some Preliminary Thoughts on Chiyoko Szlavnics’ Music Makis Solomos Listening to Chiyoko Szlavnics’ music opens up broad questions having to do with music, aesthetics, and human existence. The Canadian composer achieves significant depth in dealing with these questions in a variety of works, including chamber-orchestra music—Heliotrope (2007); pieces with electronics—Constellations I–III for piano and sine waves (2011); chamber music, such as the recordings collected here; and multichannel sound installations. Her compositions also vary widely in duration, ranging from short pieces, such as the five-minute-long chamber-orchestra piece Wind in the Ceiling (2004–2005), to longer ones, such as the forty-five-minute Interior Landscapes II A for sine waves (2010). Chiyoko Szlavnics clearly positions herself within the recent North American tradition of such composers as Morton Feldman and James Tenney (Szlavnics studied with Tenney)—a practice that eschews the old tradition of development, replacing it instead with a new world of "immersion in sound". -

Weirdo Canyon Dispatch 2018

Review: Roadburn Thursday 19th April 2017 By Sander van den Driesche It’s that time of the year again, the After Yellow Eyes it’s straight to the much anticipated annual pilgrimage to Main Stage to see Dark Buddha Rising Tilburg to join with many hundreds of perform with Oranssi Pazuzu as the travellers for Walter’s party at Waste of Space Orchestra, which is Roadburn. As I get off the train the another highly anticipated show, and in heat kicks me right in the face, what a this case one that won’t be played massive difference to the dull and rainy anywhere else (as far as I know). What morning I left behind in Scotland. This happened on that big stage was is glorious weather for a Roadburn phenomenal, we witnessed a near hour Festival! Bring it on! of glorious drone-infused psychedelic proggy doom. In fact, it felt a bit too early for me personally in the timing of the festival to experience such an extraordinarily mind-blowing set, but it was a remarkable collaboration and performance. I can’t wait for the Live at Roadburn release to come out (someone make it happen please!). Yellow Eyes by Niels Vinck After getting my bearings with the new venues, I enter Het Patronaat for the first of my highly anticipated performances of the festival, Yellow Eyes. But after three blistering minutes of ferocious black metal the PA system seems to disagree and we have our first “Zeal & Ardor moment” of 2018. It’s Waste of Space Orchestra by Niels Vinck not even remotely funny to see the On the same Main Stage, Earthless Roadburn crew frantically trying to played the first of their sets as figure out what went wrong, but luckily Roadburn’s artist in residence. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Timbre Perception

HST.725 Music Perception and Cognition, Spring 2009 Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology Course Director: Dr. Peter Cariani Timbre perception www.cariani.com Friday, March 13, 2009 overview Roadmap functions of music sound, ear loudness & pitch basic qualities of notes timbre consonance, scales & tuning interactions between notes melody & harmony patterns of pitches time, rhythm, and motion patterns of events grouping, expectation, meaning interpretations music & language Friday, March 13, 2009 Wikipedia on timbre In music, timbre (pronounced /ˈtæm-bər'/, /tɪm.bər/ like tamber, or / ˈtæm(brə)/,[1] from Fr. timbre tɛ̃bʁ) is the quality of a musical note or sound or tone that distinguishes different types of sound production, such as voices or musical instruments. The physical characteristics of sound that mediate the perception of timbre include spectrum and envelope. Timbre is also known in psychoacoustics as tone quality or tone color. For example, timbre is what, with a little practice, people use to distinguish the saxophone from the trumpet in a jazz group, even if both instruments are playing notes at the same pitch and loudness. Timbre has been called a "wastebasket" attribute[2] or category,[3] or "the psychoacoustician's multidimensional wastebasket category for everything that cannot be qualified as pitch or loudness."[4] 3 Friday, March 13, 2009 Timbre ~ sonic texture, tone color Paul Cezanne. "Apples, Peaches, Pears and Grapes." Courtesy of the iBilio.org WebMuseum. Paul Cezanne, Apples, Peaches, Pears, and Grapes c. 1879-80); Oil on canvas, 38.5 x 46.5 cm; The Hermitage, St. Petersburg Friday, March 13, 2009 Timbre ~ sonic texture, tone color "Stilleben" ("Still Life"), by Floris van Dyck, 1613. -

131 the Ambiguity of Musical Expression Marks and the Challenges

The Ambiguity of Musical Expression Marks and the Challenges of Teaching and Learning Keyboard Instruments: The Nnamdi Azikiwe University Experience Ikedimma Nwabufo Okeke http://dx.doi./org/10.4314/ujah.v18i1.7 Abstract The relevance of musical expression marks —technical words, symbols, phrases, and their abbreviations— in music is to guide the performer through a thorough interpretation and appreciation of the dynamics and subtleties of a piece of music. These marks, though fundamental to piano pedagogy, sometimes appear confusing to the enthusiastic piano student owing to the fact that some of the performance marks demand subjective expressions from the performer such as, ‘furiously’, ‘fiercely’ ‘with agitation’ ‘brightly’, tenderly, etc. Piano-keyboard education is still a ‘tender’ art in Nigerian higher institutions where most learners start at a relatively very late age (17-30 yrs) and so, it becomes burdensome and sometimes unproductive to encumber the undergraduate piano-keyboard student with a plethora of performance marks when he is still grappling with scales and arpeggios. This paper therefore suggests teaching keyboard basics and technique and employing fundamental musical expression marks/dynamics first for undergraduate piano teaching and learning in our institutions. Only when students have shown competences in the basic dynamic/expression marks such as, crescendo, accelerando, andante, moderato, allegro, larghetto etc, can the more complex and subjective ones be introduced in their keyboard repertoire. 131 Okeke: The Ambiguity of Musical Expression Marks Introduction The New Harvard dictionary of Music (2001) defines musical expression/performance marks as ‘symbols and words or phrases and their abbreviations employed along with musical notation to guide the performance of a work in matters other than pitches and rhythms’.