The Silver Age Dailies and Sundays 1966-1967

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Les Reprints Made in U.S

Pas d'équivoques pour BD/VF chez Glénat qui s'intitule elle-même la BD de papa. La série les reprints des Rip Kirby d'Alex Raymond constitue une excellente initiation au bon vieux roman poli- made in U.S. cier de derrière les fagots pour adolescents en quête de suspense. Malheureusement le format des vignettes la rend difficile à lire alors que la par Claude-Anne Parmegiani, parution en album broché permet un prix de la Joie par les livres vente abordable pour un public jeune. Chez Futuropolis, la présentation soignée de la col- Ils s'appellent Pim, Pam, Poum, Terry, Po- lection « Copyright » la destine aux pères et aux peye, Illico, Blondie ou bien Flash Gordon, Rip grands frères. Dommage que le format en lon- Kirby, Mandrake, Superman, Prince Valiant... gueur et l'épais cartonnage ne facilitent pas la Ils sont tantôt petits, moches, rigolos et dé- manipulation des trois volumes de Popeye (Se- brouillards, tantôt grands, beaux, forts et invin- gar) ou de Superman (Siegel et Shuster), qui cibles. Ils sont tous supers ! mais ce sont quand plairaient dès douze ans sous une forme plus même les copains d'enfance de nos parents. populaire et à un prix plus abordable. Car à cet Alors pourquoi cette brusque nostalgie de l'âge âge-là, on lit et on relit « ses » BD jusqu'à les d'or de la BD américaine chez les éditeurs ? savoir par cœur, et pour ça pas d'autre moyen Pierre Horay avait déjà ouvert la voie en réé- que les acheter ; on peut pas compter sur les ditant depuis une dizaine d'années les classi- parents pour vous les offrir ! Quand ils les ques de la BD dont le chef-d'œuvre de Windsor aiment, ils les gardent pour eux, sinon ils trou- Me Cay : Little Nemo. -

Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop the DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY

$39.99 “The period covered in this volume is arguably one of the strongest in the Gould/Tracy canon, (Different in Canada) and undeniably the cartoonist’s best work since 1952's Crewy Lou continuity. “One of the best things to happen to the Brutality by both the good and bad guys is as strong and disturbing as ever…” comic market in the last few years was IDW’s decision to publish The Complete from the Introduction by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop THE DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY NEARLY 550 SEQUENTIAL COMICS OCTOBER 1954 In Volume Sixteen—reprinting strips from October 25, 1954 THROUGH through May 13, 1956—Chester Gould presents an amazing MAY 1956 Chester Gould (1900–1985) was born in Pawnee, Oklahoma. number of memorable characters: grotesques such as the He attended Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State murderous Rughead and a 467-lb. killer named Oodles, University) before transferring to Northwestern University in health faddist George Ozone and his wild boys named Neki Chicago, from which he was graduated in 1923. He produced and Hokey, the despicable "Nothing" Yonson, and the amoral the minor comic strips Fillum Fables and The Radio Catts teenager Joe Period. He then introduces nightclub photog- before striking it big with Dick Tracy in 1931. Originally titled Plainclothes Tracy, the rechristened strip became one of turned policewoman Lizz, at a time when women on the the most successful and lauded comic strips of all time, as well force were still a rarity. Plus for the first time Gould brings as a media and merchandising sensation. -

Superman Or Batman Cakes

2105-8507SMnBatWebIs50530.qxd 7/12/05 11:42 AM Page 1 Instructions for To Decorate Superman Cake To make the Superman cake in the colors shown you will need Wilton Baking & Decorating Icing Colors in Royal Blue, Christmas Red, Copper (skin tone), and Lemon Yellow, tips 3, 16 and 18. We suggest that you tint all icing at Superman or Batman one time while cake cools. Refrigerate tinted icings in covered containers until ready to use. Cakes Make 3 cups buttercream icing: 1 PLEASE READ THROUGH INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE YOU BEGIN. • Tint 1 ⁄2 cups blue 3 IN ADDITION, to decorate cakes you will need: • Tint ⁄4 cup red • Tint 1⁄4 cup copper (skin tone) • Wilton Decorating Bag and Coupler or • Tint 1⁄4 cup yellow parchment paper triangles • Reserve 1⁄4 cup white • Tips 3, 16, and 18 • Wilton Icing Colors in Royal Blue, WITH RED ICING WITH YELLOW ICING • Use tip 3 and “To Outline” • Use tip 16 and “To Make Stars” Christmas Red, Copper (skin tone), directions to outline details on cape directions to cover belt Lemon Yellow and Black • Use tip 18 and “To Make Stars” • Use tip 16 and “To Make Stars” • Serving plate directions to cover cape directions to squeeze out a second • One 2-layer cake mix or ingredients for layer of stars in a circle to give the your favorite layer cake recipe WITH BLUE ICING appearance of a belt buckle • 3 cups buttercream icing (recipe) or • Use tip 3 and “To Outline” directions to outline details on suit WITH RED ICING 2 packages of creamy vanilla type • Use tip 16 and “To Make Stars” frosting mix (15.4 oz. -

Keane, for Allowing Us to Come and Visit with You Today

BIL KEANE June 28, 1999 Joan Horne and myself, Ann Townsend, interviewers for the Town of Paradise Valley Historical Committee are privileged to interview Bil Keane. Mr. Keane has been a long time resident of the Town of Paradise Valley, but is best known and loved for his cartoon, The Family Circus. Thank you, Mr. Keane, for allowing us to come and visit with you today. May we have your permission to quote you in part or all of our conversation today? Bil Keane: Absolutely, anything you want to quote from it, if it's worthwhile quoting of course, I'm happy to do it. Ann Townsend: Thank you very much. Tell us a little bit about yourself and what brought you to hot Arizona? Bil Keane: Well, it was a TWA plane. I worked on the Philadelphia Bulletin for 15 years after I got out of the army in 1945. It was just before then end of 1958 that I had been bothered each year with allergies. I would sneeze in the summertime and mainly in the spring. Then it got in to be in the fall, then spring, summer and fall. The doctor would always prescribe at that time something that would alleviate it. At the Bulletin I was doing a regular comic and I was editor of their Fun Book. I had a nine to five job there and we lived in Roslyn which was outside Philadelphia and it was one hour and a half commute on the train and subway. I was selling a feature to the newspapers called Channel Chuckles, which was the little cartoon about television which I enjoyed doing. -

{PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50'S Horror and SF Comics by Alex Toth

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50's Horror and S.F. Comics by Alex Toth Dick Briefer's Frankenstein: The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics HC (2010 IDW) comic books. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 1st printing. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. Frankenstein! Dick Briefer is one of the seminal artists who worked with Will Eisner on some of the very first comic books. If you like the comic-book weirdness of cartoonists Fletcher Hanks, Basil Wolverton, and Boody Rogers, you're sure to thrill over Dick Briefer's creation of Frankenstein. The large-format book lovingly reproduces a monstrous number of stories from the original 1940s and '50s comic books. The stories are fascinatingly supplemented by an insightful introduction with rare photos of the artist, original art, letters from Dick Briefer, drawings by Alex Toth inspired by Briefer's Frankenstein-and much more! Hardcover, 112 pages, full color. Cover price $21.99. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 2nd or later printings. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

Batman: Riddler's Ransom (Pdf)

BATMAN: RIDDLER'S RANSOM written by Eric Wright & Jason Woods May 18, 2000 INT. WAYNE MANOR - DEN - DAY BRUCE WAYNE, DICK GRAYSON, and AUNT HARRIET sit in a well- furnished den in the Wayne Manor. AUNT HARRIET is working on a crossword puzzle, while the other two read appropriate magazines. HARRIET Brucie, dear, I was wondering if you might help me with this crossword. One of the clues has me stumped. BRUCE Of course. HARRIET Why thank you. Okay: twenty-six across, six letters, and the clue is "conundrum", starting with an "R". BRUCE (looks thoughtfully.) I believe the answer is... "riddle". (They all smile, relieved.) ALFRED The telephone for you, Sir. BRUCE Thank you, Alfred. (to the others) I'll take this...in the other room. BRUCE WAYNE and DICK GRAYSON exchange knowing glances. INT. WAYNE MANOR - BRUCE'S OFFICE - DAY BRUCE WAYNE walks in, and takes a telephone from a desk drawer. He looks cautiously right and left, and then picks up the receiver. BRUCE Yes? GORDON Batman: we have a problem. CUT TO: OPENING THEME SONG AND TITLES 2. FADE OUT FADE IN: INT. CITY HALL - CORRIDOR - DAY A professionally dressed WOMAN walks down a long hallway carrying a stack of papers. Her footsteps echo. She walks up to a door at the end of the hallway, which has a sign on or near it that reads "Mayor, Gotham City". She pushes open the door. INT. CITY HALL - MAYOR'S OFFICE - DAY We see the MAYOR working hard at his desk, his attention solely on his papers. -

5 Expos Lesclat Dels Classics L

L’esclat dels clàssics Còmics i tebeos (1900-1950) DIPUTACIÓ DE VALÈNCIA EXPOSICIONS/EXPOSICIONES Textos Vicent Sanchis, Enric Melego, Valeria Suárez President de la Diputació de València/Presidente de la “L’esclat dels clàssics: Contrastos entre els grans mestres de Diputació de València la historieta nord-americana (1900-1945)” Traducció a l’anglés dels textos/Traducción al inglés de los Antoni Francesc Gaspar Ramos textos Comissari/Comisario Begoña García Soler Diputat de l’Àrea de Cultura/Diputado del Área de Cultura Enric Melego i Trilles Xavier Rius i Torres Coordinació tècnica/Coordinación técnica Muntatge/Montaje María José Navarro Josearte SL MUSEU VALENCIÀ DE LA IL·LUSTRACIÓ I DE LA Disseny expositiu/Diseño expositivo Pintura MODERNITAT (MUVIM) Alejandro Muñoz Ariño Teodosio Caballero Rodas Enmarcat/Enmarcado Director Disseny gràfic/Diseño gráfico Pilar Torrijos Rafael Company i Mateo Valeria Suárez Conde Transport/Transporte Subdirectora Textos Art i clar Carmen Ninet Vicent Sanchis, Enric Melego, Alejandro Muñoz, Valeria Suárez Il·luminació/Iluminación Cap d’exposicions/Jefe de exposiciones Grupo Luz Amador Griñó Traducció a l’anglés dels textos/Traducción al inglés de los textos Assegurances/Seguros Cap d’Investigació i Gestió Cultural/Jefe de investigación Begoña García Soler Generalli y gestión cultural Marc Borràs i Barberà Correcció de textos/Corrección de textos Fons procedents de col·leccions privades Unitat de Normalització Lingüística de la Diputació de Fondos procedentes de colecciones privadas Cap de protocol i -

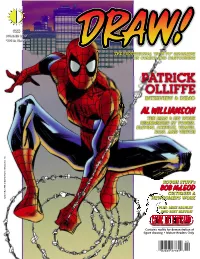

Patrick Olliffe Interview & Demo Al Williamson the Man & His Work Remembered by Torres, Blevins, Schultz, Yeates, Ross, and Veitch

#23 SUMMER 2012 $7.95 In The US THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS AND CARTOONING PATRICK OLLIFFE INTERVIEW & DEMO AL WILLIAMSON THE MAN & HIS WORK REMEMBERED BY TORRES, BLEVINS, SCHULTZ, YEATES, ROSS, AND VEITCH ROUGH STUFF’s BOB McLEOD CRITIQUES A Spider-Man TM Spider-Man & ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc. NEWCOMER’S WORK PLUS: MIKE MANLEY AND BRET BLEVINS’ Contains nudity for demonstration of figure drawing • Mature Readers Only 0 2 1 82658 27764 2 THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS & CARTOONING WWW.DRAW-MAGAZINE.BLOGSPOT.COM SUMMER 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOL. 1, NO. 23 Editor-in-Chief • Michael Manley Designer • Eric Nolen-Weathington PAT OLLIFFE Publisher • John Morrow Mike Manley interviews the artist about his career and working with Al Williamson Logo Design • John Costanza 3 Copy-Editing • Eric Nolen- Weathington Front Cover • Pat Olliffe DRAW! Summer 2012, Vol. 1, No. 23 was produced by Action Planet, Inc. and published by TwoMorrows Publishing. ROUGH CRITIQUE Michael Manley, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Bob McLeod gives practical advice and Editorial address: DRAW! Magazine, c/o Michael Manley, 430 Spruce Ave., Upper Darby, PA 19082. 22 tips on how to improve your work Subscription Address: TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Dr., Raleigh, NC 27614. DRAW! and its logo are trademarks of Action Planet, Inc. All contributions herein are copyright 2012 by their respective contributors. Action Planet, Inc. and TwoMorrows Publishing accept no responsibility for unsolicited submissions. All artwork herein is copyright the year of produc- THE CRUSTY CRITIC tion, its creator (if work-for-hire, the entity which Jamar Nicholas reviews the tools of the trade. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph.