Egypt, Arab Republic Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EG-Helwan South Power Project Raven Natural Gas Pipeline

EG-Helwan South Power Project The Egyptian Natural Gas Company Raven Natural Gas Pipeline ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT June 2019 Final Report Prepared By: 1 ESIA study for RAVEN Pipeline Pipeline Rev. Date Prepared By Description Hend Kesseba, Environmental I 9.12.2018 Specialist Draft I Anan Mohamed, Social Expert Hend Kesseba, Environmental II 27.2.2019 Specialist Final I Anan Mohamed, Social Expert Hend Kesseba, Environmental Final June 2019 Specialist Final II Anan Mohamed, Social Expert 2 ESIA study for Raven Pipeline Executive Summary Introduction The Government of Egypt (GoE) has immediate priorities to increase the use of the natural gas as a clean source of energy and let it the main source of energy through developing natural gas fields and new explorations to meet the national gas demand. The western Mediterranean and the northern Alexandria gas fields are planned to be a part from the national plan and expected to produce 900 million standard cubic feet per day (MMSCFD) in 2019. Raven gas field is one of those fields which GASCO (the Egyptian natural gas company) decided to procure, construct and operate a new gas pipeline to transfer rich gas from Raven gas field in north Alexandria to the western desert gas complex (WDGC) and Amreya Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) plant in Alexandria. The extracted gas will be transported through a new gas pipeline, hereunder named ‘’the project’’, with 70 km length and 30’’ inch diameter to WDGC and 5 km length 18” inch diameter to Amreya LPG. The proposed project will be funded from the World Bank(WB) by the excess of fund from the south-helwan project (due to a change in scope of south helwan project, there is loan saving of US$ 74.6 m which GASCO decided to employ it in the proposed project). -

Whole-Genome Sequencing for Tracing the Genetic Diversity of Brucella Abortus and Brucella Melitensis Isolated from Livestock in Egypt

pathogens Article Whole-Genome Sequencing for Tracing the Genetic Diversity of Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis Isolated from Livestock in Egypt Aman Ullah Khan 1,2,3 , Falk Melzer 1, Ashraf E. Sayour 4, Waleed S. Shell 5, Jörg Linde 1, Mostafa Abdel-Glil 1,6 , Sherif A. G. E. El-Soally 7, Mandy C. Elschner 1, Hossam E. M. Sayour 8 , Eman Shawkat Ramadan 9, Shereen Aziz Mohamed 10, Ashraf Hendam 11 , Rania I. Ismail 4, Lubna F. Farahat 10, Uwe Roesler 2, Heinrich Neubauer 1 and Hosny El-Adawy 1,12,* 1 Institute of Bacterial Infections and Zoonoses, Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, 07743 Jena, Germany; AmanUllah.Khan@fli.de (A.U.K.); falk.melzer@fli.de (F.M.); Joerg.Linde@fli.de (J.L.); Mostafa.AbdelGlil@fli.de (M.A.-G.); mandy.elschner@fli.de (M.C.E.); Heinrich.neubauer@fli.de (H.N.) 2 Institute for Animal Hygiene and Environmental Health, Free University of Berlin, 14163 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] 3 Department of Pathobiology, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences (Jhang Campus), Lahore 54000, Pakistan 4 Department of Brucellosis, Animal Health Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Dokki, Giza 12618, Egypt; [email protected] (A.E.S.); [email protected] (R.I.I.) 5 Central Laboratory for Evaluation of Veterinary Biologics, Agricultural Research Center, Abbassia, Citation: Khan, A.U.; Melzer, F.; Cairo 11517, Egypt; [email protected] 6 Sayour, A.E.; Shell, W.S.; Linde, J.; Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Elzera’a Square, Abdel-Glil, M.; El-Soally, S.A.G.E.; Zagazig 44519, Egypt 7 Veterinary Service Department, Armed Forces Logistics Authority, Egyptian Armed Forces, Nasr City, Elschner, M.C.; Sayour, H.E.M.; Cairo 11765, Egypt; [email protected] Ramadan, E.S.; et al. -

Alexandria's Hinterland

Alexandria’s Hinterland Archaeology of the Western Nile Delta, Egypt Mohamed Kenawi Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 014 3 ISBN 978 1 78491 015 0 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and M Kenawi 2014 Front cover: Baths, Kom al-Ahmer (Mohamed Kenawi); Kom Wasit, Aerial photo 2014 (copyright Italian Mission in Beheira, photographer Henrik Brahe. http://www.caiecentroarcheologico.org/ and http://www.komahmer.com/). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by CMP (UK) Ltd This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com This work is dedicated to Mariette de Vos Raaijmakers Emanuele Papi Contents List of Figures ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iii List of Plates ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� viii List of Maps ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ viii List of Tables ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Country Report of Egypt *

HIGH LEVEL FORUM ON GLOBAL CONFERENCE ROOM PAPER GEOSPATIAL MANAGEMENT INFORMATION NO. 4 First Forum Seoul, Republic of Korea, 24-26 October 2011 Country Report of Egypt * ___________________ * Submitted by: Mrs. Nahla Seddik Mohammed Saleh, Engineer in the GIS Department, Central Agency for Public Mobilization And Statistics 1 High Level Forum on Global Geospatial Information Management Seoul – Republic of Korea 24-26 October 2011 Egypt Report On The Development and Innovations of Egypt National geospatial Information System Prepared by Eng. Nahla Seddik Mohammed Director of Communication Systems Unit in GIS Department [email protected] CAPMAS,CAIRO, Nasr City, Salah Salem Street,B.O,BOX:2086 Tel:002024024986 Fax:002022611066 [email protected] www.capmas.gov.eg About The Department The Geographical Information Systems Department was established in 1989, to do the following tasks: 1. Establishment the administrative boundaries of Egypt for all three levels(Governorate- Ksm\Mrkz-shiakha\village). 2. Creating the digital base maps on the level of provinces Republic on a scale of 1:5000 (The coverage of digital base maps for urban areas of the republic is nearly 100%). 3. Produce different types of maps which are used in surveys, censuses and researches which are produced by CAPMAS. 4. Offering the consultations and technical support to government and private sector to build geographic information systems units from A to Z. 5. Supplying the needs of universities and research sectors by providing digital maps, cartography maps and various geographic data. 6. Continuously follow up updating of all geographical data bases for base maps and administrative boundaries at all scales of maps. -

Final Assessment of the Egypt Child Survival Project (263-0203)

FINAL ASSESSMENT OF THE EGYPT CHILD SURVIVAL PROJECT (263-0203) POPTECH Report No. 96-073-41 August 1996 by Laurel K. Cobb Franklin C. Baer Marc J. P. Debay Mohamed A. ElFeraly Ahmed Kashmiry Prepared for Edited and Produced by U.S. Agency for International Development Population Technical Assistance Project Mission to Egypt 1611 North Kent Street, Suite 508 (USAID/Egypt) Arlington, VA 22209 USA Contract No. CCP-3024-Q-00-3012 Phone: 703/247-8630 Project No. 936-3024 Fax: 703/247-8640 The observations, conclusions, and recommendations set forth in this document are those of the authors alone and do not represent the views or opinions of POPTECH, BHM International, The Futures Group International, or the staffs of these organizations. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................v MAJOR CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .......................... ix 1. BACKGROUND ...........................................................1 1.1 Early Implementation of Project .......................................1 1.2 Midterm Evaluation .................................................2 1.3 Response to Midterm Evaluation ......................................2 1.4 Project Organization and Management .................................3 1.5 Child Mortality Trends, 1985-1995 .....................................3 2. EXPANDED PROGRAM ON IMMUNIZATION (EPI) ..........................7 2.1 Goals and Outputs Review .............................................7 -

Efficiency of the Using of Human and Machine the Sources in Wheat Production in Beheira Governorate

Available online at http://www.journalijdr.com International Journal of Development Research ISSN: 2230-9926 Vol. 11, Issue, 07, pp. 48934-48940, July, 2021 https://doi.org/10.37118/ijdr.22437.07.2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS EFFICIENCY OF THE USING OF HUMAN AND MACHINE THE SOURCES IN WHEAT PRODUCTION IN BEHEIRA GOVERNORATE Ashraf M. El Dalee1,*, Lamis F. Elbahenasy2, Safaa M. Elwakeel2 and Eman A. Ibrahim3 1Professor Researcher, Agricultural Economics Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center –Egypt 2Senior Researcher, Agricultural Economics Research Institute Agricultural Research Center – Egypt 3Researcher, Agricultural Economics Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center – Egypt ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT The research problem is represented in the high costs of producing wheat crop as a result of the high prices of Article History: production requirements, which may affect the cultivated areas of it, and due to the rapid and successive Received 20th April, 2021 progress in the transfer of technology in the field of agriculture, especially agricultural operations, it has been Received in revised form possible to replace human work with automated work, after the high wages of rural labor trained women in the 10th May, 2021 fields of agriculture and continuous migration to urban areas as a result of the seasonality of agricultural Accepted 30th June, 2021 production on the one hand, and the low wages in the country side compared to the urban ones, which Published online 28th July, 2021 prompted farmers to move towards using -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report

Arab Republic of Egypt Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities European Investment Bank L’Agence Française de Développement (AFD) Construction Authority for Potable Water & Wastewater CAPW Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report Date of issue: May 2020 Consulting Engineering Office Prof. Dr.Moustafa Ashmawy Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project NTS ESIA Report Non - Technical Summary 1- Introduction In Egypt, the gap between water and sanitation coverage has grown, with access to drinking water reaching 96.6% based on CENSUS 2006 for Egypt overall (99.5% in Greater Cairo and 92.9% in rural areas) and access to sanitation reaching 50.5% (94.7% in Greater Cairo and 24.3% in rural areas) according to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). The main objective of the Project is to contribute to the improvement of the country's wastewater treatment services in one of the major treatment plants in Cairo that has already exceeded its design capacity and to improve the sanitation service level in South of Cairo at Helwan area. The Project for the ‘Expansion and Upgrade of the Arab Abo Sa’ed (Helwan) Wastewater Treatment Plant’ in South Cairo will be implemented in line with the objective of the Egyptian Government to improve the sanitation conditions of Southern Cairo, de-pollute the Al Saff Irrigation Canal and improve the water quality in the canal to suit the agriculture purposes. This project has been identified as a top priority by the Government of Egypt (GoE). The Project will promote efficient and sustainable wastewater treatment in South Cairo and expand the reclaimed agriculture lands by upgrading Helwan Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) from secondary treatment of 550,000 m3/day to advanced treatment as well as expanding the total capacity of the plant to 800,000 m3/day (additional capacity of 250,000 m3/day). -

Daring to Care Reflections on Egypt Before the Revolution and the Way Forward

THE ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANTS IN EGYPT Daring To Care Reflections on Egypt Before The Revolution And The Way Forward Experts’ Views On The Problems That Have Been Facing Egypt Throughout The First Decade Of The Millennium And Ways To Solve Them Daring to Care i Daring to Care ii Daring to Care Daring to Care Reflections on Egypt before the revolution and the way forward A Publication of the Association of International Civil Servants (AFICS-Egypt) Registered under No.1723/2003 with Ministry of Solidarity iii Daring to Care First published in Egypt in 2011 A Publication of the Association of International Civil Servants (AFICS-Egypt) ILO Cairo Head Office 29, Taha Hussein st. Zamalek, Cairo Registered under No.1723/2003 with Ministry of Solidarity Copyright © AFICS-Egypt All rights reserved Printed in Egypt All articles and essays appearing in this book as appeared in Beyond - Ma’baed publication in English or Arabic between 2002 and 2010. Beyond is the English edition, appeared quarterly as a supplement in Al Ahram Weekly newspaper. Ma’baed magazine is its Arabic edition and was published independently by AFICS-Egypt. BEYOND-MA’BAED is a property of AFICS EGYPT No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission of AFICS Egypt. Printed in Egypt by Moody Graphic International Ltd. 7, Delta st. ,Dokki 12311, Giza, Egypt - www.moodygraphic.com iv Daring to Care To those who have continuously worked at stirring the conscience of Egypt, reminding her of her higher calling and better self. -

News Coverage Prepared For: the European Union Delegation to Egypt

News Coverage Prepared for: The European Union delegation to Egypt Disclaimer: “This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of authors of articles and under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of IPSOS or the European Union.” 1 Newspapers (29/11/2011) Election Coverage 2 Al Ahram Newspaper Page: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 Author: Mohamed Enz, Amany Maged, Sameh Lashen, Mohamed Hamada, Ibrahim Omran, Abdel-Gawad Ali, Wageh el-Saqqar, Badawi el-Sayed Negela, Amr Ali el- Far, Mohamed Zakaria, Nehad Samir, Ahmed el-Hawari, Essam Ali Refaat, Fekri Abdel-Salam, Nasser Geweda, Tareq Ismail, Rami Yassin, Mohamed Shear, Mohamed Abdel-Khaleq, Sherif Gaballah, Gamal Abul-Dahab, Ashraf Sadeq, Khaled Ahmed el-Motani, Ali Sham, Abdel-Gawad Tawfiq, Hala el-Sayed and Amal Awadallah Since the early morning of Monday, people have been lining up to cast their ballots in the first phase of the parliamentary elections, probably the first time in their lives. According to preliminary indications in the nine governorates, where the first stage of the elections are taking place, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice (FJP) and Salafist Al-Nour Party led the race in Cairo. Al-Nour Party seemed to be strongly competing in Alexandria, Fayoum and Kafr El- Sheikh. In the Southern Cairo constituency, voters stood in lines that lasted for over one kilometer. In Alexandria, vehicles belonging to candidates, wondered the streets to wake up voters since the small hours of Monday to cast their votes. -

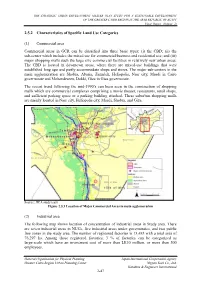

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

País Região Cidade Nome De Hotel Morada Código Postal Algeria

País Região Cidade Nome de Hotel Morada Código Postal Algeria Adrar Timimoun Gourara Hotel Timimoun, Algeria Algeria Algiers Aïn Benian Hotel Hammamet Ain Benian RN Nº 11 Grand Rocher Cap Caxine , 16061, Aïn Benian, Algeria Algeria Algiers Aïn Benian Hôtel Hammamet Alger Route nationale n°11, Grand Rocher, Ain Benian 16061, Algeria 16061 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Safir Alger 2 Rue Assellah Hocine, Alger Centre 16000 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Samir Hotel 74 Rue Didouche Mourad, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Albert Premier 5 Pasteur Ave, Alger Centre 16000 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Suisse 06 rue Lieutenant Salah Boulhart, Rue Mohamed TOUILEB, Alger 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Aurassi Hotel El-Aurassi, 1 Ave du Docteur Frantz Fanon, Alger Centre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre ABC Hotel 18, Rue Abdelkader Remini Ex Dujonchay, Alger Centre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Space Telemly Hotel 01 Alger, Avenue YAHIA FERRADI, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hôtel ST 04, Rue MIKIDECHE MOULOUD ( Ex semar pierre ), 4, Alger Ctre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Dar El Ikram 24 Rue Nezzar Kbaili Aissa, Alger Centre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Oran Center 44 Rue Larbi Ben M'hidi, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Es-Safir Hotel Rue Asselah Hocine, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Dar El Ikram 22 Rue Hocine BELADJEL, Algiers, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre