A Comparative Study of Metacognitive Strategies In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

I LLINOJ S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. BULLETIN THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LIBRARY * CHILDREN'S BOOK CENTER Volume IX July, 1956 Number 11 EXPLANATION OF CODE SYMBOLS USED WITH ANNOTATIONS R Recommended M Marginal book that is so slight in content or has so many weaknesses in style or format that it barely misses an NR rating. The book should be given careful consideration before purchase. NR Not recommended. Ad For collections that need additional material on the subject. SpC Subject matter or treatment will tend to limit the book to specialized collections. SpR A book that will have appeal for the unusual reader only. Recommended for the special few who will read it. step in the process. At the end there is a simple experiment that children could do at home. A useful book for units on foods or industries. A" W andan ?1ouz "Eofsh R Adler, Irving. Fire in Your Life; illus. R Annixter, Jane and Paul. The Runner; 6-9 by Ruth Adler. Day, 1955. 128p. 7-9 drawings by Paul Laune. Holiday House, $2.75 1956. 220p. $2.75. In much the same style as his Time in Your Clem Mayfield (Shadow), an orphan living with Life and Tools in Your Life, the author traces his aunt and uncle on their Wyoming ranch, is the history of man's use of fire from primitive recovering from a bout with polio that left him to modern times. Beginning with some of the with a limp but still able to ride. -

Endangered Species Act: Beyond Collective Rights for Species

WALTZ-MACRO-012720 (DO NOT DELETE) 2/13/2020 5:04 PM The “Embarrassing” Endangered Species Act: Beyond Collective Rights for Species Danny Waltz∗ I. Introduction ..................................................................................... 2 II. Philosophical backdrop ............................................................... 11 A. Collective and Individual Rights in the Human Context ........ 12 1. Two Views on Collective Rights ............................................ 12 2. The Historical Arc from Individual to Collective Rights ..... 14 3. Against the Grain: Gun Rights, From the Collective to the Individual ....................................................................... 16 B. Collective and Individual Rights in the Nonhuman Animal Context ....................................................................... 18 1. Collective Rights for Animals ................................................ 19 2. Moral Complications with Collective Rights ........................ 20 3. Individual Animal Rights at the Experience Level .............. 23 III. Individual Animal Rights in the Endangered Species Act ........ 27 A. Purpose ...................................................................................... 27 B. Operative Text Provisions ......................................................... 29 1. Section 4: Listing .................................................................. 29 2. Section 7: Jeopardy ............................................................... 32 3. Section 9: “Take” ................................................................. -

From Your PTA Co-President, Margaret Editor: Laurie Weissman Happy Spring Everyone! You I Don’T Think I Could Have Made It Through the Year

Volume 11, Issue 2 June, 2011 From your PTA Co-President, Margaret Editor: Laurie Weissman Happy Spring everyone! you I don’t think I could have made it through the year. These Moms are so As I look around our school, I see the resourceful, caring and most of all dedi- flowers blooming and hear the cheer- cated in everything they do. A hug goes ful giggles of children. It reminds me to my Co-President Leslie, great job! that spring is here and summer is not Her dedication and support made this too far away. The halls and play- year a fun and enjoyable one. Leslie you ground are full of life and excitement. have so many great ideas, keep going, we I see the changes in the children, they all could benefit from them. I don’t like all seem so confident and sure of to say goodbye so I'll say see you all themselves. It is hard to believe that later. I am confident that with our new another year at Lee Road has gone so Co-President Roma and the wise knowl- quickly. This year seemed to fly by so edge of Leslie our school PTA is going to fast. I think one reason was due to the be a strong one. I want to wish the amount of support I had. I would like graduating fifth graders a big congrats to thank Mr. Goss for helping and and best wishes in Salk. I'd like to end supporting me and the PTA. When with saying I hope everyone has a fun you have a principal that is open to filled summer. -

(Tableau Des Électeurs Sénatoriaux

ELECTIONS SENATORIALES TABLEAU DES ELECTEURS Commune Civ nom prénom qualité Remplaçant de M JÉGO Yves Député M JACOB Christian Député M RIESTER Franck Député M PARIGI Jean-François Député M KOKOUENDO Rodrigue Député M FAUVERGUE Jean-Michel Député M FAURE Olivier Député Mme LUQUET Aude Député Mme PEYRON Michèle Député MmeDO Stéphanie Député Mme LACROUTE Valérie Député M BILLOUT Michel Sénateur Mme BRICQ Nicole Sénateur Mme CHAIN-LARCHE Anne Sénateur M CUYPERS Pierre Sénateur M EBLÉ Vincent Sénateur Mme MELOT Colette Sénateur Mme BADRÉ Marie Pierre Conseiller régional M BATTAIL Gilles Conseiller régional M BOLLÉE Joffrey Conseiller régional M DEROUCK Marc Conseiller régional Madame Anne CHAIN-LARCHÉ M CHÉRON James Conseiller régional 1/232 ELECTIONS SENATORIALES TABLEAU DES ELECTEURS Commune Civ nom prénom qualité Remplaçant de M CHERRIER Pierre Conseiller régional M CHEVRON Benoît Conseiller régional Mme COURNET Aurélie Conseiller régional M CUZOU Gilbert Conseiller régional M DUTHEIL DE LA ROCHERE Bertrand Conseiller régional Mme FUCHS Sylvie Conseiller régional M JEUNEMAITRE Eric Conseiller régional M KALFON François Conseiller régional Mme MOLLARD-CADIX Laure-Agnès Conseiller régional Mme MONCHECOURT Sylvie Conseiller régional Mme MONVILLE-DE CECCO Bénédicte Conseiller régional M PLANCHOU Jean-Paul Conseiller régional M PROFFIT Julien Conseiller régional Mme REZEG Hamida Conseiller régional Mme SARKISSIAN Roseline Conseiller régional Mme THOMAS Claudine Conseiller régional Mme TROUSSARD Béatrice Conseiller régional M VALLETOUX Frédéric -

Mens a Jason Daniels Richard Dunn John Meeks ADULT

DIVISION TEAM PLAYER ONE PLAYER TWO PLAYER THREE ADULT - Mens A Jason Daniels Richard Dunn John Meeks ADULT - Mens A Mayhem Lee Binkley Mark Binkley Austin Neiheiser ADULT - Mens A COVID Spikes Cameron Brence Logan Brence Chanse Myers ADULT - Mens A Stoned Aged Romeos Jason Lewis Tim Dudley Maeson LuCan ADULT - Mens A Dig My Ballz Tommy Criss John Owens Owen Sease ADULT - Mens A CHHS Bois Nathan Dye Zin Maung Drew Campbell ADULT - Mens A Burhan Bustillos Jay Park Elliot Kim ADULT - Mens A I'd Hit That Zach Lamoureux Hayden Lichty Hunter Davis ADULT - Mens A The 1995 Wisconsin Badgers Patrick Shugart Kevin Troupe Joel Cordray ADULT - Mens A Don't Set Sarum Sarum Rich Micah Johnson Christian Sullivan ADULT - Mens A Justin Burgess Addison Musser ADULT - Mens BB Hit Men Andrew Wild Andrew Cecil Jeremy Wollman ADULT - Mens BB We ALWAYS get it up Scott Drogue Nolan Franz Timmy Shaw ADULT - Mens BB Nguyen Tran TBD TBD TBD TBD ADULT - Mens BB The Chimps stephen carbone Stephen carbone kenny nguyen ADULT - Mens BB Hang 10 Matt Lenora Blaine Ott David Mumford ADULT - Mens BB The Heat Brandon Wooding Gary Biggs Darius Swanson ADULT - Mens BB Block Heads Charlie Sapp Johnny Kearns Kane Laah ADULT - Mens BB What the Pho. Jp Phetx Andy Inth Phy Phy ADULT - Mens BB Barry Rymer Artie Sykes Danny Sutton ADULT - Mens BB Bum Squad Trevor Chaney Quan Pratt Caleb Williams ADULT - Mens BB Raleigh Raccoons Sion Tran David Eban Sam Vong ADULT - Mens BB Ken Phanhvilay Lefoi Falemalama Dustin Rhodes ADULT - Mens BB Just three bros Peyton Robinson Chris Burkett -

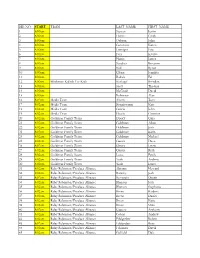

Step up List

BIB NO. START TEAM LAST_NAME FIRST_NAME 1 8:00am Stewart Justin 2 8:00am Harris Cindy 3 8:00am Osborn John 4 8:00am Geninatti Karen 5 8:00am Leninger Eric 6 8:00am Frey Kristin 7 8:00am Harris James 8 8:00am Sanchez Roxanne 9 8:00am Noll Byron 10 8:00am Glenn Jennifer 11 8:00am Badida Ed 12 8:00am Blackman Kallick For Kids Kinkopf Brendan 13 8:00am Scott Thomas 14 8:00am McGrath David 15 8:00am Robinson Alan 16 8:02am Media Team Ahern Tom 17 8:02am Media Team Bongiovanni Kate 18 8:02am Media Team Garcia John 19 8:02am Media Team Garcia Christine 20 8:02am Goldman Family Team Doocy Gina 21 8:02am Goldman Family Team Goldman Adam 22 8:02am Goldman Family Team Goldman Josh 23 8:02am Goldman Family Team Goldman Karla 24 8:02am Goldman Family Team Goldman Michael 25 8:02am Goldman Family Team Gussis Dave 26 8:02am Goldman Family Team Gussis Lizzie 27 8:02am Goldman Family Team Gussis Ruth 28 8:02am Goldman Family Team Lowe Emily 29 8:02am Goldman Family Team York Andrew 30 8:02am Goldman Family Team York Laura 31 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Abrams Howard 32 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Barasky Jodi 33 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Bernstein Dustin 34 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Blanton Josh 35 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Blanton Stephanie 36 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Breen Barbara 37 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Breen Daniel 38 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Breen Katie 39 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Breen Mike 40 8:02am Ruby Robinson/Produce Alliance Capone -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

The Compassion Arts & Culture and Animals Festival

The Compassion Arts & Culture and Animals Festival Featuring the World Premiere of And the Hummingbird Says . by Mihoko Suzuki and Martin Rowe Leonard Nimoy Thalia Theater at Symphony Space 2537 Broadway, New York City Saturday October 21, 2017: 1:45–3:45 pm and 7:30–10:30 pm Sunday October 22, 2017: 1:45–5:30 pm and 7:30–11:00 pm plus an art exhibition: Friday 5:00 pm–Sunday 6:00 pm at 208 E. 73rd St. Art Show: Beasts of Burden Festival Schedule Our Complex Relationship with Animals Featuring art by Jo-Anne McArthur, Moby, Performances Jennifer Wynne Reeves, Jane O’Hara, Karen Fiorito, Nancy Diessner, Wendy Klemperer, Tony Openings Bevilacqua, Denise Lindquist, Gedas Paskauskas, Ariel Bordeaux, Adonna Khare, Raul Gonzalez III, Julia Oldham, and Moira McLaughlin. Events O’Hara Projects. 208 East 73rd Street SUNDAY OCTOBER 22—AFTERNOON (Off Third Ave at TUF Gallery) 11 am–6 pm: Art Show: Beasts of Burden FRIDAY OCTOBER 20 O’Hara Projects. 208 East 73rd Street. 5–8 pm: Art Show: Beasts of Burden Reception 1:45 pm: Introduction and Welcome 2:00 pm: The Music of Michael Harren: a multi- SATURDAY OCTOBER 21—AFTERNOON media performance blending humor with candor 11 am–6 pm: Art Show: Beasts of Burden to convey the importance of keeping all animals O’Hara Projects. 208 East 73rd Street. safe from harm. With string quartet. 1:45 pm: Introduction and Welcome 3:00 pm: Break 2:00 pm: And the Hummingbird Says . : Composed 3:15 pm: Kedi (2016): dir. by Ceyda Torun, about the by Mihoko Suzuki, with words by Martin street cats of Istanbul. -

Royal Valley Third Grade

2017 Christmas Greetings & Letters to Santa Claus Seventh-month-old Zoey Casas-Sanchez (shown above) of Holton was pret- ty comfortable during a recent visit with Santa Claus at the Jackson County Braxton Luthi (shown above), 2, was happy to meet and take pictures Courthouse. Zoey and her parents, Alexis and Carlos, stopped by the Court- with Santa Claus during a recent trip to Holton. Braxton is the son of house to take family photos with the jolly old elf. Photo by Ali Holcomb Adam and Skyler Luthi. Adam is a native of Holton. Photo by Ali Holcomb Royal Valley Third Grade The following are letters to Dear Santa been good this year. I promise By: Isabelle M., Meriden/ gingerbread house or cookies Love, Eli, Hoyt Santa Claus from Sonya Linn’s I want shades for Christmas to lay out your favorite cookies Hoyt with milk, but whatever you third grade class at Royal Valley and a Jayhawk hat. Is Rudolph andk mil and carrots for Ru- want you can have milk. I hope Dear Santa, Elementary School. real? I will be sure to leave dolph. Thank you for the Xbox Dear Santa, you can bring all the reindeer How are your reindeer? Can I cookies and milk and carrots. One last year and the presents How are you doing? I have and hope Rudolph doesn’t have please have an ice cream maker Dear Santa, Tell everyone at the North Pole the year before and the year be- been good this year and the to guide the sleigh and I hope and an easy bake oven? Can you What is your favorite cookie? Merry Christmas! fore. -

2-Year-Old Filly Trotters

2-YEAR-OLD FILLY TROTTERS Leg 1 Leg 2 Leg 3 Leg 4 ELIGIBLE HORSES Sire Dam NP 7/3 SD 7/20 NP 8/6 SD 8/28 Allaboutadream X X X X Uncle Peter Inevitable All Along X X X X Dejarmbro Nantab All For You X X X X Uncle Peter Nordic Nymph All Of China X X X X Dejarmbro Great Hall of China And Many More X X X X Manofmanymissions Cavier N Chardoney And Up We Go X X X X And Away We Go Miss Giai D Aunt Bee's Jewel X X X X Uncle Peter Keep Me In Mind Auntie Percilla X X X X Uncle Peter I Lazue Aunt Marilynn X X X X Uncle Peter Poster Pin Up Aunt Rose X X X X Uncle Peter Lightning Flower Aunt Suzanna X X X X Uncle Peter Aleah Hanover Back Splash X X X X Triumphant Caviar Splashabout Bad Babysitter X X X X Manofmanymissions My Baby's Momma Bank On Tiffany X X X X Break The Bank K Tiffany Bella MacDuff X X X X Manofmanymissions Whata Star Bentontriumph X X X X Triumphant Caviar Bentley Seelster Beyond Amazing X X X X Dontyouforgetit Pine Career Box Cars X X X X Manofmanymissions Prettysydney Ridge Brandy Fine Girl X X X X Dontyouforgetit Yankeedoodledandy Break Hearts X X X X Break The Bank K Sweetie Hearts Breakthemagic X X X X Break The Bank K Magic Peach Broadway Mimi X X X X Broadway Hall Mini Marvelous Bye Bye Broadway X X X X Broadway Hall Classy Messenger Caia X X X X Manofmanymissions Cedada Caring Moment X X X X Uncle Peter Emotional Rescue Cash In The Chips X X X X Break The Bank K Miss Chip K Cathy Jo's Triumph X X X X Triumphant Caviar Winter Green CC Cashorcredit X X X X Dejarmbro Take Em Cash Counting Her Moni X X X X Break The Bank K Sheknowsherlines -

Postconflict and Conflict Behavior in All-Male Groups of Captive Western Lowland Gorillas (Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla) Jackie Elizabeth Davenport Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 Postconflict and conflict behavior in all-male groups of captive western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) Jackie Elizabeth Davenport Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Anthropology Commons, Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Other Psychology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Davenport, Jackie Elizabeth, "Postconflict and conflict behavior in all-male groups of captive western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla)" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15342. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15342 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Postconflict and conflict behavior in all-male groups of captive western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla ) by Jackie Elizabeth Davenport A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: Anthropology Program of Study Committee: Jill Pruetz, Major Professor Sue Fairbanks Chrisy Moutsatsos Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 Copyright © Jackie Elizabeth Davenport, 2008. All rights reserved. 453164 1453164 2008 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Overview 1 1.2 Conflict in Gorilla Society 3 1.3 Postconflict Behavior 7 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 12 2.1 The Sociality of Gorillas 12 2.2 A Closer Look at Wild Male Gorillas 33 CHAPTER 3. -

Editor & Publisher International Year Books

Content Survey & Selective Index For Editor & Publisher International Year Books *1929-1949 Compiled by Gary M. Johnson Reference Librarian Newspaper & Current Periodical Room Serial & Government Publications Division Library of Congress 2013 This survey of the contents of the 1929-1949 Editor & Publisher International Year Books consists of two parts: a page-by-page selective transcription of the material in the Year Books and a selective index to the contents (topics, names, and titles) of the Year Books. The purpose of this document is to inform researchers about the contents of the E&P Year Books in order to help them determine if the Year Books will be useful in their work. Secondly, creating this document has helped me, a reference librarian in the Newspaper & Current Periodical Room at the Library of Congress, to learn about the Year Books so that I can provide better service to researchers. The transcript was created by examining the Year Books and recording the items on each page in page number order. Advertisements for individual newspapers and specific companies involved in the mechanical aspects of newspaper operations were not recorded in the transcript of contents or added to the index. The index (beginning on page 33) attempts to provide access to E&P Year Books by topics, names, and titles of columns, comic strips, etc., which appeared on the pages of the Year Books or were mentioned in syndicate and feature service ads. The headings are followed by references to the years and page numbers on which the heading appears. The individual Year Books have detailed indexes to their contents.