UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canaan Or Gaza?

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Pa-Canaan in the Egyptian New Kingdom: Canaan or Gaza? Michael G. Hasel Institute of Archaeology, Southern Adventist University A&564%'6 e identification of the geographical name “Canaan” continues to be widely debated in the scholarly literature. Cuneiform sources om Mari, Amarna, Ugarit, Aššur, and Hattusha have been discussed, as have Egyptian sources. Renewed excavations in North Sinai along the “Ways of Horus” have, along with recent scholarly reconstructions, refocused attention on the toponyms leading toward and culminating in the arrival to Canaan. is has led to two interpretations of the Egyptian name Pa-Canaan: it is either identified as the territory of Canaan or the city of Gaza. is article offers a renewed analysis of the terms Canaan, Pa-Canaan, and Canaanite in key documents of the New Kingdom, with limited attention to parallels of other geographical names, including Kharu, Retenu, and Djahy. It is suggested that the name Pa-Canaan in Egyptian New Kingdom sources consistently refers to the larger geographical territory occupied by the Egyptians in Asia. y the 1960s, a general consensus had emerged regarding of Canaan varied: that it was a territory in Asia, that its bound - the extent of the land of Canaan, its boundaries and aries were fluid, and that it also referred to Gaza itself. 11 He Bgeographical area. 1 The primary sources for the recon - concludes, “No wonder that Lemche’s review of the evidence struction of this area include: (1) the Mari letters, (2) the uncovered so many difficulties and finally led him to conclude Amarna letters, (3) Ugaritic texts, (4) texts from Aššur and that Canaan was a vague term.” 12 Hattusha, and (5) Egyptian texts and reliefs. -

Undergraduate Journal of Middle East Studies University of Toronto Undergraduate Journal of Middle East Studies

university of toronto of toronto university studies east middle of journal undergraduate 7 issue undergraduate journal of middle east studies ISSUE 7—2014 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO University of Toronto Undergraduate Journal of Middle East Studies A publication of the University of Toronto Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations Students’ Union ISSUE 7, 2013-2014 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Cover photo by Shirin Shahidi Jameh Mosque, Isfahan (December 2012) Please address all inquiries, comments, and subscription requests to: University of Toronto Undergraduate Journal of Middle East Studies c/o Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations Students’ Union Bancroft Building, 2nd Floor 4 Bancroft Avenue Toronto, ON Canada M5S 1C1 [email protected] ISSN 1710-4920 Copyright © 2014 University of Toronto Undergraduate Journal of Middle East Studies A note from the editors 3 It is with great privilege and honour that we present to you the undergraduate journal of middle east studies seventh edition of the Undergraduate Journal of Middle East Studies. This year, our Journal celebrates ten years of excellence in writing and research in the field of Middle East studies. For this occasion, our team has taken the initiative of reviving the original format and design of the Journal which has proven to be a challenging but rewarding task. Since its inception in 2004, editors have striven to provide an academic forum for undergraduate students to engage in scholarly discussion regarding a region that is often discussed but seldom understood. As in previous issues, our authors seek to present readers with diverse perspectives upon the Middle East, echoing our Journal’s mandate: to depict a non-monolithic portrait of the region. -

The Cradle of Pyramids.Wps

The cradle of pyramids in satellite images Amelia Carolina Sparavigna Dipartimento di Fisica, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy We propose the use of image processing to enhance the Google Maps of some archaeological areas of Egypt. In particular we analyse that place which is considered the cradle of pyramids, where it was announced the discovery of a new pyramid by means of an infrared remote sensing. Saqqara and Dahshur are burial places of the ancient Egypt. Saqqara was the necropolis of Memphis, the ancient capital of the Lower Egypt. This place has many pyramids, including the well-known step pyramid of Djoser, and several mastabas. As told in Wikipedia, 16 Egyptian kings built pyramids there and the high officials added their tombs during the entire pharaonic period [1]. The necropolis remained an important complex for non-royal burials and cult ceremonies till the Roman times. Dahshur is another royal necropolis located in the desert on the west bank of the Nile [2]. The place is well-known for several pyramids, two of which are among the oldest and best preserved in Egypt. Therefore this site can be properly considered as the cradle of Egyptian pyramids [3]. Figure 1 shows the Djoser pyramid and the Great Enclosure at Saqqara. The two images have been obtained from Google Maps after an image processing with two programs, AstroFracTool, based on the calculus of the fractional gradient, and the wavelet filtering of Iris, as discussed in Ref.4. The reader can compare the images with the original Google Maps, using the coordinates given in the figure [5]. -

Cambridge Archaeological Journal 15:2, 2005

Location of the Old Kingdom Pyramids in Egypt Miroslav Bârta The principal factors influencing the location of the Old Kingdom pyramids in Egypt are reconsidered. The decisive factors influencing their distribution over an area of c. eighty kilometres were essentially of economic, géomorphologie, socio-political and unavoidably also of religious nature. Primary importance is to be attributed to the existence of the Old Kingdom capital of Egypt, Memphis, which was a central place with regard to the Old Kingdom pyramid fields. Its economic potential and primacy in the largely redistribution- driven state economy sustained construction of the vast majority of the pyramid complexes in its vicinity. The location of the remaining number of the Old Kingdom pyramids, including many of the largest ever built, is explained using primarily archaeological evidence. It is claimed that the major factors influencing their location lie in the sphere of general trends governing ancient Egyptian society of the period. For millennia, megaliths and monumental arts were pyramids see Edwards 1993; Fakhry 1961; Hawass commissioned by the local chieftains and later by the 2003; Lehner 1997; Stadelmann 1985; 1990; Vallogia kings of Egypt. The ideological reasons connected 2001; Verner 2002; Dodson 2003). The reasons that may with the construction and symbolism of the pyra be put forward to explain their location and arrange mids were manifold, and in most cases obvious: the ment are numerous but may be divided into two basic manifestation of power, status and supremacy over groups: practical and religious. It will be argued that the territory and population, the connection with the whereas the general pattern in the distribution of the sacred world and the unlimited authority of the rulers pyramid sites may be due mainly to practical reasons, (O'Connor & Silverman 1995). -

Famous Pharaohs

Ancient Egyptians: History Information Sheet Famous Pharaohs Name: Khufu Name: Khafra Reigned: 2589 - 2566 BC Reigned: 2558 - 2504 BC Khufu is also known as King Cheops and Khafra is famous for building the is the builder of the Great Pyramid of second of the pyramids at Giza and the Giza. The Giza pyramids are famous as Sphinx which guards his tomb. Some being the oldest of the Seven Ancient historians believe that the head of the Wonders of the World and the only one Sphinx is carved in Khafra’s image. to still be in existence today. Name: Ankhenaten Name: Hatshepsut Reigned:1351 - 1337 BC Reigned: 1472 - 1457 BC Ankhenaten is most remembered for Hatshepsut is remembered not only changing the belief system of ancient because she was a woman (it was very Egypt, if only for a short while. He rare for a woman to be a ruler) but also introduced Aten, a sun god, as the one because of the many accomplishments true god and changed Egypt from a she achieved throughout her reign. kingdom that worshiped many gods to During her reign, trade flourished, the a kingdom that worshiped just one. economy grew and she built and restored many magnificent temples Name: Rameses II and other buildings. Reigned: 1279 - 1213 BC Rameses II is also known as Rameses Name: Tutankhamen the Great. He was a great military ruler Reigned: 1334 - 1325 BC and famously defeated the Hittites to Tutankhamen is not remembered for his regain control of lands that had been reign as king as much as he is famous lost during the reign of Ankhenaten. -

Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part 45: Birds Statues (Falcon and Vulture)

International Journal of Emerging Engineering Research and Technology Volume 5, Issue 3, March 2017, PP 39-48 ISSN 2349-4395 (Print) & ISSN 2349-4409 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.22259/ijeert.0503004 Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part 45: Birds Statues (Falcon and Vulture) Galal Ali Hassaan (Emeritus Professor), Department of Mechanical Design & Production, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt ABSTRACT The evolution of mechanical engineering in ancient Egypt is investigated in this research paper through studying the production of statues and figurines of falcons and vultures. Examples from historical eras between Predynastic and Late Periods are presented, analysed and aspects of quality and innovation are outlined in each one. Material, dynasty, main dimension (if known) and present location are also outlined to complete the information about each statue or figurine. Keywords: Mechanical engineering, ancient Egypt, falcon statues, vulture statues INTRODUCTION This is the 45th paper in a scientific research aiming at presenting a deep insight into the history of mechanical engineering during the ancient Egyptian civilization. The paper handles the production of falcon and vulture statues and figurines during the Predynastic and Dynastic Periods of the ancient Egypt history. This work depicts the insight of ancient Egyptians to birds lived among them and how they authorized its existence through statuettes and figurines. Smith (1960) in his book about ancient Egypt as represented in the Museum of Fine Arts at Boston presented a number of bird figurines including ducks from the Middle Kingdom, gold ibis from the New Kingdom and a wooden spoon in the shape of a duck and lady from the New Kingdom [1]. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

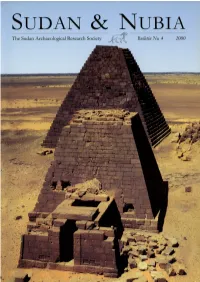

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Was the Function of the Earliest Writing in Egypt Utilitarian Or Ceremonial? Does the Surviving Evidence Reflect the Reality?”

“Was the function of the earliest writing in Egypt utilitarian or ceremonial? Does the surviving evidence reflect the reality?” Article written by Marsia Sfakianou Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom..........................2 How writing began.........................................................................................................4 Scopes of early Egyptian writing...................................................................................6 Ceremonial or utilitarian? ..............................................................................................7 The surviving evidence of early Egyptian writing.........................................................9 Bibliography/ references..............................................................................................23 Links ............................................................................................................................23 Album of web illustrations...........................................................................................24 1 Map of Egypt. Late Predynastic Period-Early Dynastic (Grimal, 1994) Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom (from the appendix of Grimal’s book, 1994, p 389) 4500-3150 BC Predynastic period. 4500-4000 BC Badarian period 4000-3500 BC Naqada I (Amratian) 3500-3300 BC Naqada II (Gerzean A) 3300-3150 BC Naqada III (Gerzean B) 3150-2700 BC Thinite period 3150-2925 BC Dynasty 1 3150-2925 BC Narmer, Menes 3125-3100 BC Aha 3100-3055 BC -

The Iconography of the Princess in the Old Kingdom 119 Vivienne G

THE OLD KINGDOM ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE HELD IN PRAGUE, MAY 31 – JUNE 4, 2004 Miroslav Bárta editor Czech Institute of Egyptology Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague Academia Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Prague 2006 OOKAApodruhéKAApodruhé sstrtr ii–xii.indd–xii.indd 3 99.3.2007.3.2007 117:18:217:18:21 Contributors Nicole Alexanian, James P. Allen, Susan Allen, Hartwig Altenmüller, Tarek El Awady, Miroslav Bárta, Edith Bernhauer, Edward Brovarski, Vivienne G. Callender, Vassil Dobrev, Laurel Flentye, Rita Freed, Julia Harvey, Salima Ikram, Peter Jánosi, Nozomu Kawai, Jaromír Krejčí, Kamil O. Kuraszkiewicz, Renata Landgráfová, Serena Love, Dušan Magdolen, Peter Der Manuelian, Ian Mathieson, Karol Myśliwiec, Stephen R. Phillips, Gabriele Pieke, Ann Macy Roth, Joanne M. Rowland, Regine Schulz, Yayoi Shirai, Nigel Strudwick, Miroslav Verner, Hana Vymazalová, Sakuji Yoshimura, Christiane Ziegler © Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, 2006 ISBN 80-200-1465-9 OOKAApodruhéKAApodruhé sstrtr ii–xii.indd–xii.indd 4 99.3.2007.3.2007 117:18:217:18:21 Contents Foreword ix Bibliography xi Tomb and social status. The textual evidence 1 Nicole Alexanian Some aspects of the non-royal afterlife in the Old Kingdom 9 James P. Allen Miniature and model vessels in Ancient Egypt 19 Susan Allen Presenting the nDt-Hr-offerings to the tomb owner 25 Hartwig Altenmüller King Sahura with the precious trees from Punt in a unique scene! 37 Tarek El Awady The Sixth Dynasty tombs in Abusir. Tomb complex of the vizier Qar and his family 45 Miroslav Bárta Die Statuen mit Papyrusrolle im Alten Reich 63 Edith Bernhauer False doors & history: the Sixth Dynasty 71 Edward Brovarski The iconography of the princess in the Old Kingdom 119 Vivienne G. -

Nilotic Livestock Transport in Ancient Egypt

NILOTIC LIVESTOCK TRANSPORT IN ANCIENT EGYPT A Thesis by MEGAN CHRISTINE HAGSETH Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Shelley Wachsmann Committee Members, Deborah Carlson Kevin Glowacki Head of Department, Cynthia Werner December 2015 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2015 Megan Christine Hagseth ABSTRACT Cattle in ancient Egypt were a measure of wealth and prestige, and as such figured prominently in tomb art, inscriptions, and even literature. Elite titles and roles such as “Overseer of Cattle” were granted to high ranking officials or nobility during the New Kingdom, and large numbers of cattle were collected as tribute throughout the Pharaonic period. The movement of these animals along the Nile, whether for secular or sacred reasons, required the development of specialized vessels. The cattle ferries of ancient Egypt provide a unique opportunity to understand facets of the Egyptian maritime community. A comparison of cattle barges with other Egyptian ship types from these same periods leads to a better understand how these vessels fit into the larger maritime paradigm, and also serves to test the plausibility of aspects such as vessel size and design, composition of crew, and lading strategies. Examples of cargo vessels similar to the cattle barge have been found and excavated, such as ships from Thonis-Heracleion, Ayn Sukhna, Alexandria, and Mersa/Wadi Gawasis. This type of cross analysis allows for the tentative reconstruction of a vessel type which has not been identified previously in the archaeological record. -

Buhen in the New Kingdom

Buhen in the New Kingdom George Wood Background - Buhen and Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom Traditionally ancient Egypt ended at the First Cataract of the Nile at Elephantine (modern Aswan). Beyond this lay Lower Nubia (Wawat), and beyond the Dal Cataract, Upper Nubia (Kush). Buhen sits just below the Second Cataract, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Wadi Halfa, at what would have been a good location for ships to carry goods to the First Cataract. The resources that flowed from Nubia included gold, ivory, and ebony (Randall-MacIver and Woolley 1911a: vii, Trigger 1976: 46, Baines and Málek 1996: 20, Smith, ST 2004: 4). Egyptian operations in Nubia date back to the Early Dynastic Period. Contact during the 1st Dynasty is linked to the end of the indigenous A-Group. The earliest Egyptian presence at Buhen may have been as early as the 2nd Dynasty, with a settlement by the 3rd Dynasty. This seems to have been replaced with a new town in the 4th Dynasty, apparently fortified with stone walls and a dry moat, somewhat to the north of the later Middle Kingdom fort. The settlement seems to have served as a base for trade and mining, and royal seals from the 4th and 5th Dynasties indicate regular communications with Egypt (Trigger 1976: 46-47, Baines and Málek 1996: 33, Bard 2000: 77, Arnold 2003: 40, Kemp 2004: 168, Bard 2015: 175). The latest Old Kingdom royal seal found was that of Nyuserra, with no archaeological evidence of an Egyptian settlement after the reign of Djedkara. -

Specular Reflection from the Great Pyramid at Giza

Specular Reflection from the Great Pyramid at Giza Donald E. Jennings Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA (retired) email: [email protected] Posted to arXiv: physics.hist-ph April 6, 2021 Abstract The pyramids of ancient Egypt are said to have shone brilliantly in the sun. Surfaces of polished limestone would not only have reflected diffusely in all directions, but would also likely have produced specular reflections in particular directions. Reflections toward points on the horizon would have been visible from large distances. On a particular day and time when the sun was properly situated, an observer stationed at a distant site would have seen a momentary flash as the sun’s reflection moved across the face of the pyramid. The positions of the sun that are reflected to the horizon are confined to narrow arcs in the sky, one arc for each side of the pyramid. We model specular reflections from the pyramid of Khufu and derive the annual dates and times when they would have been visible at important ancient sites. Certain of these events might have coincided with significant dates on the Egyptian calendar, as well as with solar equinoxes, solstices and cross-quarter days. The celebration of Wepet-Renpet, which at the time of the pyramid’s construction occurred near the spring cross-quarter day, would have been marked by a specular sweep of sites on the southern horizon. On the autumn and winter cross-quarter days reflections would have been directed to Heliopolis. We suggest that on those days the pyramidion of Khafre might have been visible in specular reflection over the truncated top of Khufu’s pyramid.