Conn Cétchathach and the Image of Ideal Kingship in Early Medieval Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume II

7+( &(/7,& (1&<&/23(',$ 92/80( ,, . T H E C E L T I C E N C Y C L O P E D I A © HARRY MOUNTAIN VOLUME II UPUBLISH.COM 1998 Parkland, Florida, USA The Celtic Encyclopedia © 1997 Harry Mountain Individuals are encouraged to use the information in this book for discussion and scholarly research. The contents may be stored electronically or in hardcopy. However, the contents of this book may not be republished or redistributed in any form or format without the prior written permission of Harry Mountain. This is version 1.0 (1998) It is advisable to keep proof of purchase for future use. Harry Mountain can be reached via e-mail: [email protected] postal: Harry Mountain Apartado 2021, 3810 Aveiro, PORTUGAL Internet: http://www.CeltSite.com UPUBLISH.COM 1998 UPUBLISH.COM is a division of Dissertation.com ISBN: 1-58112-889-4 (set) ISBN: 1-58112-890-8 (vol. I) ISBN: 1-58112-891-6 (vol. II) ISBN: 1-58112-892-4 (vol. III) ISBN: 1-58112-893-2 (vol. IV) ISBN: 1-58112-894-0 (vol. V) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mountain, Harry, 1947– The Celtic encyclopedia / Harry Mountain. – Version 1.0 p. 1392 cm. Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-58112-889-4 (set). -– ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1). -- ISBN 1-58112-891-6 (v. 2). –- ISBN 1-58112-892-4 (v. 3). –- ISBN 1-58112-893-2 (v. 4). –- ISBN 1-58112-894-0 (v. 5). Celts—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D70.M67 1998-06-28 909’.04916—dc21 98-20788 CIP The Celtic Encyclopedia is dedicated to Rosemary who made all things possible . -

Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol.117C, Pp.65-99

Gleeson P. (2017) Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, vol.117C, pp.65-99. Copyright: This is the author’s accepted manuscript of an article that has been published in its final definitive form by the Royal Irish Academy, 2017. Link to article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3318/priac.2017.117.04 Date deposited: 07/04/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Luigne Breg and the origins of the Uí Néill By Patrick Gleeson, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University Email: [email protected] Phone: (+44) 01912086490 Abstract: This paper explores the enigmatic kingdom of Luigne Breg, and through that prism the origins and nature of the Uí Néill. Its principle aim is to engage with recent revisionist accounts of the various dynasties within the Uí Néill; these necessitate a radical reappraisal of our understanding of their origins and genesis as a dynastic confederacy, as well as the geo-political landsape of the central midlands. Consequently, this paper argues that there is a pressing need to address such issues via more focused analyses of local kingdoms and political landscapes. Holistic understandings of polities like Luigne Breg are fundamental to framing new analyses of the genesis of the Uí Néill based upon interdisciplinary assessments of landscape, archaeology and documentary sources. In the latter part of the paper, an attempt is made to to initiate a wider discussion regarding the nature of kingdoms and collective identities in early medieval Ireland in relation to other other regions of northwestern Europe. -

Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung As a Junction Within Lebor Gabála Érenn

Edinburgh Research Explorer Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn Citation for published version: Thanisch, E 2013, Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn. in Quaestio Insularis: Selected Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium in Anglo-Saxon Norse and Celtic. vol. 13, pp. 69-93. <http://www.asnc.cam.ac.uk/publications/quaestio/Quaestio2012.html> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Quaestio Insularis General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor 1 Gabála Érenn INTRODUCTION Lebor Gabála Érenn: Content Lebor Gabála Érenn (‘the Book of the Invasion of Ireland’) is the conventional title for a lengthy Irish pseudo-historical text extant in multiple recensions probably compiled during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.2 The text comprises a history of the Gaídil (‘Gaels’) within the context of a universal history derived from the Bible and from Classical historiography.3 Lebor Gabála traces the ancestry of the Gaídil back to Noah and follows their tortuous migrations, spanning many generations, from the Tower of Babel to Ireland via Spain. -

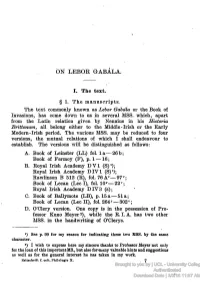

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

1 Clontarf 1014

Clontarf 1014 – a battle of the clans? 1. The contemporary record In its account of the battle of Clontarf the northern AU report that Brian, son of Cennétig, king of Ireland, and Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, king of Tara, led an army to Dublin (Áth Cliath) • all of the Leinsterman (Laigin) were assembled to meet him (Brian), the foreigners of Áth Cliath, and a similar number of foreigners of Lochlainn (Scotland) • a sterling battle was fought between them, the like of which had never been encountered before Then the foreigners and the Leinstermen first broke in defeat and were completely wiped out • there fell on the side of the foreign troop Máel Mórda, king of Leinster, and Domnall, king of the Forthuatha • of the foreigners fell Dubgall, son of Amlaíb (= Óláfr), Sigurd, earl (jarl) of Orkney, and Gilla Ciaráin, heir designate of the foreigners, etc. • Brodar who slew Brian, chief of the Scandinavian fleet, together with 6,000 others was also killed or drowned Of the Irish who fell in the counter-shock were Brian, overking of the Irish of Ireland and of the foreigners [of Limerick and Waterford] and of the Britons [of Wales?], the Augustus of the whole of the north-west of Europe [= Ireland] • his son Murchad and the latter’s son Tairdelbach, Conaing, the heir designate of Mumu, Mothla, king of the Déisi Muman, etc. • the list includes numerous kings of various parts of Munster, plus Domnall, the earl of Marr in Scotland • this list carries conviction when analysed against known details The southern AI report similarly, though more -

The Phylogenealogy of R-L21: Four and a Half Millennia of Expansion and Redistribution

The phylogenealogy of R-L21: four and a half millennia of expansion and redistribution Joe Flood* * Dr Flood is a mathematician, economist and data analyst. He was a Principal Research Scientist at CSIRO and has been a Fellow at a number of universities including Macquarie University, University of Canberra, Flinders University, University of Glasgow, University of Uppsala and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. He was a foundation Associate Director of the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. He has been administrator of the Cornwall Y-DNA Geographic Project and several surname projects at FTDNA since 2007. He would like to give credit to the many ‘citizen scientists’ who made this paper possible by constructing the detailed R1b haplotree over the past few years, especially Alex Williamson. 1 ABSTRACT: Phylogenealogy is the study of lines of descent of groups of men using the procedures of genetic genealogy, which include genetics, surname studies, history and social analysis. This paper uses spatial and temporal variation in the subclade distribution of the dominant Irish/British haplogroup R1b-L21 to describe population changes in Britain and Ireland over a period of 4500 years from the early Bronze Age until the present. The main focus is on the initial spread of L21-bearing populations from south-west Britain as part of the Beaker Atlantic culture, and on a major redistribution of the haplogroup that took place in Ireland and Scotland from about 100 BC. The distributional evidence for a British origin for L21 around 2500 BC is compelling. Most likely the mutation originated in the large Beaker colony in south-west Britain, where many old lineages still survive. -

Literature and Learning in Early Medieval Meath

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Literature and learning in early medieval Meath Author(s) Downey, Clodagh Publication Date 2015 Downey, Clodagh (2015) 'Literature and Learning in Early Publication Medieval Meath' In: Crampsie, A., and Ludlow, F(Eds.). Information Meath History and Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County. Dublin : Geography Publications. Publisher Geography Publications Link to publisher's http://www.geographypublications.com/product/meath-history- version society/ Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/7121 Downloaded 2021-09-26T15:35:58Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. CHAPTER 04 - Clodagh Downey 7/20/15 1:11 PM Page 1 CHAPTER 4 Literature and learning in early medieval Meath CLODAGH DOWNEY The medieval literature of Ireland stands out among the vernacular literatures of western Europe for its volume, its diversity and its antiquity, and within this treasury of cultural riches, Meath holds a prominence greatly disproportionate to its geographical extent, however that extent is reckoned. Indeed, the first decision confronting anyone who wishes to consider this subject is to define its geographical limits: the modern county of Meath is quite a different entity to the medieval kingdom of Mide from which it gets its name and which itself designated different areas at different times. It would be quite defensible to include in a survey of medieval literature those areas which are now under the administration of other modern counties, but which may have been part of the medieval kingdom at the time that that literature was produced. -

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge David Noel Wilson, B.A. Hon., Grad. Dip. Data Processing, Grad. Dip. History. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts (with Advanced Seminars component) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. July, 2004 © David N. Wilson 1 Abstract David Noel Wilson, Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge. This is a study of an early Irish heroic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of the Cooley). It examines the role and function of honour, both within the tale and within the society that produced the text. Its demonstrates how the pursuit of honour has influenced both the theme and structure of the Táin . Questions about honour and about the resolution of conflicting obligations form the subject matter of many of the heroic tales. The rewards and punishments of honour and shame are the primary mechanism of social control in societies without organised instruments of social coercion, such as a police force: these societies can be defined as being ‘honour-based’. Early Ireland was an honour- based society. This study proposes that, in honour-based societies, to act honourably was to act with ‘appropriate and balanced reciprocity’. Applying this understanding to the analysis of the Táin suggests a new approach to the reading the tale. This approach explains how the seemingly repetitive accounts of Cú Chulainn in single combat, which some scholars have found wearisome, serve to maximise his honour as a warrior in the eyes of the audience of the tale. -

" Sorrow Penny Yee Payed for My Drink": Taboo, Euphemism, and A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 395 506 FL 023 850 AUTHOR Odlin, Terence TITLE "Sorrow Penny Yee Payed for My Drink": Taboo, Euphemism, and a Phantom Substrate. CLCS Occasional Paper No. 43. INSTITUTION Trinity Coll., Dublin (Ireland). Centre for Language and Communication Studies. REPORT NO ISSN-0332-3889 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 28p.; An abbreviated version of this paper was given as a public lecture in the Centre for Language and Communication Studies (Dublin, Ireland, 1996). PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Diachronic Linguistics; *English; English Literature; Foreign Countries; *Irish; *Language Patterns; Language Role; Language Usage; *Negative Forms (Language); *Scots Gaelic; Uncommonly Taught Languages IDENTIFIERS Euphemism; Ireland; *Language Contact; Scotland; Taboo Terms ABSTRACT Possible origins for the use of "sorrow" as a negation in Hiberno-English are considered. Much of the evidence examined here comes from English literature. It is concluded that the uses of "sorrow" as negator and as euphemism probably reflect Celtic substrate influence. Structural evidence indicates that "sorrow" negation has grammaticalized properties similar to those for "devil" negation. Geographical and chronological evidence suggests that "sorrow" negation developed early in Scotland and that it was restricted mainly to Scotland and Ireland. Cultural evidence shows "sorrow" negation to be part of a long-standing tradition of taboo and'euphemism, one not unique to Celtic lands but certainly robust in those regions. Although several words in Irish and Scottish Gaelic are partial translation equivalents for "sorrow," only two have attested uses as negators and euphemisms for the devil: "donas" and "tubaiste." Of these, the former seems to have been an especially important word in Scotland and Ireland, 31though it may never have been a full-fledged negator in Irish. -

Calendar of Holidays September 2017 - September 2018

If you have any comments, questions or corrections regarding the below calendar, please contact CSEE at 800.298.4599, or [email protected]. Calendar of Holidays September 2017 - September 2018 September 1 (Begins at sundown on August 31 st) [Moves] Eid al-Adha (Islam) Eid al-Adha is the Festival of Sacrifice held at the conclusion of the Hajj. Those who can afford to do so sacrifice their best domestic animals, such as sheep or cows. This practice recalls Abraham's willingness to sacrifice his son, in obedience to God, and commemorates God's forgiveness. September 1 Church year begins (Orthodox Christianity) This day marks the beginning of the Orthodox Christian liturgical calendar. September 8 Nativity of Mary (Christianity) This feast originates in fifth century Jerusalem and celebrates the birth of the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus. This is recognized in the Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Anglican Churches. September 12 Ghambar Paitishem (Zoroastrianism) This is the third of the six Ghambar festivals in the Zoroastrian year. This five-day seasonal festival celebrates the creation of the earth, and the summer crop harvest. September 14 Holy Cross Day (Christianity) This day recognizes the Cross as a symbol of triumph in the Christian religion. The date traces back to the dedication of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher on September 14, 335. By order of Saint Helena and her son, the first Christian Roman Emperor Constantine, the church was built over the ruins of the Crucifixion and Burial sites in Israel. According to some traditions, it was also at this site that Helena found the True Cross. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

The Connachta of Táin Bó Cúailnge

Studia Celtica Posnaniensia, Vol 2 (1), 2017 doi: 10.1515/scp-2017-0003 THE CONNACHTA OF TÁIN BÓ CÚAILNGE ROMANAS BULATOVAS National University of Ireland, Maynooth ABSTRACT Advance in archaeology in the latter half of the 20th century rekindled interest in Táin Bó Cúailnge as a historical source and put the question of real-life identities of its main protagonists back on agenda. Despite the existing orthodoxy that the saga reflects fifth-century warfare between the southern Uí Néill and the Ulaid, some researchers continue questioning the role of the southern Uí Néill as well as the dates assigned to the events of the tale. In this article it is argued that the Connachta of the saga were more likely to be the northern Uí Néill. Furthermore, genealogical link between the two branches of the Uí Néill is put in doubt. Finally, it is suggested that the events of the Táin took place almost 200 years later than commonly believed. Keywords: The cattle-raid of Cooley, the Uí Néill dynasty, early medieval Ireland. 1.1. Preliminary Remarks Since T. F. O’Rahilly’s mythological approach had fallen out of favour, it became received wisdom that the Táin contains a genuine memory of warfare between Connaught and Ulster. However, researchers rarely agree which of the finer details preserved in the saga are historically accurate, most importantly the timeframe of the events the text refers to and the identities of warring factions. In a broad survey of current consensus concerning the antiquity of the Táin Ruairí Ó hUiginn presented several competing schools of thought (Ó hUiginn 1992: 32-33).