Boundary-Based Restrictions in Boundless Broadcast Media Markets: Mcconnell V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS June 22, 1973 H

21018 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS June 22, 1973 H. Res. 459. Resolution to create a Select By Mr. HEINZ (for himself, Mr. GREEN MEMORIALS Committee on Aging; to the Committee on of Pennsylvania, Mr. GuDE, Mr. REEs, Rules. and Mr. PRITCHARD): Under clause 4 of rule XXII, By Mr. RANDALL (for himself, Mr. H. Res. 461. Resolution to create a Select 263. The SPEAKER presented a memorial RIEGLE, Mr. ROBISON of New York, Committee on Aging; to the Committee on of the Legislature of the State of Louisiana, Mr. RoDINO, Mr. RoE, Mr. RosENTHAL, Rules. relative to no-fault insurance; to the Com Mr. ROYBAL, Mr. SARASIN, Mr. BAR By Mr. PEPPER: mittee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. BANES, Mr. SATTERFIELD, Mr. SEBELIUS, H. Res. 462. Resolution providing for the Mr. SEIBERLING, Mr. SKUBITZ, Mr. printing of additional copies of the House S·rEELE, Mr. STUDDS, Mr. TALCOTT, Mr. report entitled "Reform of our Correctional TEAGUE of California, Mr. THONE, Systems"; to the Committee on House PETITIONS, ETC. Mr. TIERNAN, Mr. VEYSEY, Mr. WALSH, Administratlon . Mr. WINN, Mr. WoN PAT, Mr. YATRON, H. Res. 463. Resolution providing for the Under clause 1 of rule XXII, and Mr. YouNG of Illinois): printing of additional copies of the House 243. The SPEAKER presented a petition of H. Res. 460. Resolution to create a Select report entitled "Organized Criminal Influence John H. Leach II, Newport Beach, Calif., rela Committee on Aging; to the Committee on in Horse Racing"; to the Committee on House tive to redress of grievance; to the Committee Rules. Administration. on the Judiciary. -

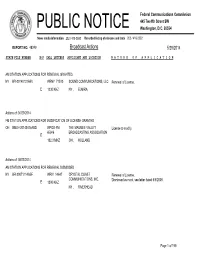

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Appendix I Waste Hauling Permit

Contents Section 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 History ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 Section 2 FOG Program Management 2.1 FOG Program Department ...................................................................................... 2-1 2.1.1 Organization ..................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1.2 Training ............................................................................................................. 2-1 2.1.3 Communications .............................................................................................. 2-3 2.2 Data Records ............................................................................................................. 2-3 2.2.1 FOG Documents .............................................................................................. 2-3 2.2.2 GIS ...................................................................................................................... 2-3 2.3 Related Documents .................................................................................................. 2-4 2.4 Quarterly Report ....................................................................................................... 2-4 Section 3 Food Establishments 3.1 Food Establishment Permits .................................................................................. -

May 16, 2014 WFAN's BOOMER & CARTON TEAM

May 16, 2014 WFAN’S BOOMER & CARTON TEAM UP WITH GIN BLOSSOMS ON MAY 23 FOR THE ‘SUMMER KICKOFF PARTY’ AT D’JAIS IN BELMAR, NEW JERSEY WFAN-AM/FM is counting down the days to summer and planning an exciting celebration to kick it off in style, with a live broadcast from morning show hosts Boomer & Carton at D’JAIS on Ocean Avenue in Belmar, New Jersey. Next Friday, May 23, Boomer Esiason & Craig Carton will host their inaugural Memorial Day “Summer Kickoff Party” with a live broadcast from 6AM – 10AM. In addition, there will be live performances by the GRAMMY® nominated band Gin Blossoms and special guests on-air during the show. Admission to the public is free, and the WFAN fan van crew will be on hand with giveaways. Tune in to WFAN on-air, streaming online at www.wfan.com and through the Radio.com app for mobile devices to hear Boomer & Carton and Gin Blossoms live from D’JAIS. Boomer & Carton – Broadcast on-air and online from 6 a.m. – 10 a.m. ET and simulcast on CBS Sports Network, the show features former NFL quarterback Boomer Esiason and radio veteran Craig Carton discussing New York sports talk with sports icons, league personnel, and a variety of national celebrities from the entertainment and music industries. For more than two decades, Gin Blossoms have defined the sound of jangle pop. From their late 80s start as Arizona’s top indie rock outfit, the Tempe-based combo has drawn critical applause and massive popular success for their trademark brand of chiming guitars, introspective lyricism, and irresistible melodies. -

Market Structure and Media Diversity Scott J. Savage, Donald M

Market Structure and Media Diversity1 Scott J. Savage, Donald M. Waldman, Scott Hiller University of Colorado at Boulder Department of Economics Campus Box 256 Boulder, CO 80309-0256 Abstract We estimate the demand for local news service described by the offerings from newspapers, radio, television, the Internet, and Smartphone. The results show that the representative consumer values diversity in the reporting of news, more coverage of multicultural issues, and more information on community news. About two-thirds of consumers have a distaste for advertising, which likely reflects their consumption of general, all-purpose advertising delivered by traditional media. Demand estimates are used to calculate the impact on consumer welfare from a marginal decrease in the number of independent television stations that lowers the amount of diversity, multiculturalism, community news, and advertising in the market. Welfare decreases, but the losses are smaller in large markets. For example, small-market consumers lose $53 million annually while large-market consumers lose $15 million. If the change in market structure occurs in all markets, total losses nationwide would be about $830 million. September 25, 2012 Key words: market structure, media diversity, mixed logit, news, welfare JEL Classification Number: C9, C25, L13, L82, L96 1 The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Time Warner Cable (TWC) Research Program on Digital Communications provided funding for this research. We are grateful to Jessica Almond, Fernando Laguarda, Jonathan Levy, and Tracy Waldon for their assistance during the completion of this project. Yongmin Chen, Nicholas Flores, Jin-Hyuk Kim, David Layton, Edward Morey, Gregory Rosston, Bradley Wimmer, and seminar participants at the University of California, University of Colorado, SUNY and attendees at the Conference in Honor of Professor Emeritus Lester D. -

Nebraska Court Rejects Newspaper Reporter's Challenge to Coverage

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © 2019 Media Law Resource Center, Inc. MLRC MediaLawLetter January 2019 Page 21 Nebraska Court Rejects Newspaper Reporter’s Challenge to Coverage of His Scuffle with Parking Attendant By Tiffany B. Gelott A Nebraska state judge dismissed a defamation case – brought, ironically, by a newspaper reporter – holding that a television station’s coverage of the reporter’s run-in with a city parking employee was substantially true and protected by the fair report privilege. See Cooper v. WOWT-Channel 6 Gray Television Group Inc., Case No. CI 18-2674 (Neb. Dist. Douglass Cty. Nov. 5, 2018). This decision provides much needed recent precedent reinforcing defamation defenses in Nebraska. The Run-In, the News Reports and the Lawsuit According to an Omaha Police Incident Report, on March 24, 2017, the Police Department received a radio call to “investigate an assault on a parking enforcement officer.” The incident began when Todd Cooper, an Omaha World-Herald reporter who covers crime, heatedly disputed a parking ticket issued by a Park Omaha employee. The parking employee, Timothy Foster, told police This decision that Cooper followed him to his vehicle, prevented him from closing provides much the door to his Park Omaha truck, and grabbed his neck, and that when needed recent Foster tried to push Cooper away, both men fell to the ground. The precedent police also took the statement of an eyewitness to the incident. reinforcing WOWT-Channel 6 in Omaha, owned by Gray Television Group, defamation defenses Inc., broadcast and posted a news report based on the Police Incident in Nebraska. -

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

DISH Network Satellite Television Brings Local TV Channels to Memphis, Tenn

DISH Network Satellite Television Brings Local TV Channels to Memphis, Tenn. Littleton, Colo., Oct. 2, 2003 - EchoStar Communications Corporation (NASDAQ: DISH) announced today that its DISH NetworkT, America's fastest growing subscription television service, now offers local TV channels by satellite television to Memphis, Tenn. The following local TV channels are now offered: ABC Ch. 24 (WPTY), CBS Ch. 3 (WREG), NBC Ch. 5 (WMC), FOX Ch. 13 (WHBQ), UPN Ch. 30 (WLMT) and PBS Ch. 10 (WKNO). This is the first time local TV channels are available by DISH Network satellite TV in the Memphis area, providing an alternative to local cable TV service. Local channels will be offered for $5.99 per month for DISH Network customers in Memphis. A Dish 500 antenna is required to receive the local channels via satellite. A second dish, available free of charge, may be required to receive UPN Ch. 30 (WLMT). "DISH Network customers now have a more affordable alternative to cable in Memphis," said Michael Schwimmer, senior vice president of Programming at EchoStar. "DISH Network provides local news, weather and sports in 100 percent digital quality to viewers who should not be left with cable service as their only choice for local television." DISH Network offers local channels via satellite to Memphis customers in three states including 10 Tennessee counties: Crockett, Dyer, Fayette, Gibson, Hardeman, Haywood, Lauderdale, McNairy, Shelby and Tipton. Memphis local channels are also available in seven Arkansas counties: Crittenden, Cross, Lee, Mississippi, Phillips, Poinsett and St. Francis as well as 11 Mississippi counties: Alcorn, Benton, Coahoma, De Sota, Lafayette, Marshall, Panola, Quitman, Tate, Tippah and Tunica. -

WHERE to WATCH STADIUM Active Markets As of 7/13/18

WHERE TO WATCH STADIUM Active markets as of 7/13/18 MARKET STATE STATION CH. # Albany-Schenectady-Troy NY WCWN-4 45.4 Albuquerque-Santa Fe NM KTFQ-4 41.4 Amarillo TX KVII-4/KVIH-4 7.4/12.4 Atlanta GA WDWW LD-3 28.3 Austin TX KGBS (dot?) 32.1 Bakersfield CA KBFX-4 29.4 Beamont/Port Arthur TX KBTV-4 4.4 Biloxi-Gulfport MS WXVO LD-4 7.4 Birmingham (Ann and Tusc) AL WBMA-3 58.3 Boise ID KYUU-4 35.4 Boston (Manchester) MA WUTF-4 27.4 Buffalo NY WNYO-2 49.2 Cedar Rapids-Waterloo-Iowa City-Dubuque IA KFXA-4 28.4 Champaign IL WBUI-3 23.3 Charleston-Huntington WV WVAH-2 11.2 Charlotte NC WVEB LD-3 40.3 Chicago IL WRJK LP-4 22.4 Cincinnati OH WKRC-3 12.3 Cleveland-Akron OH WQDI D-4 20.4 Columbia SC WACH-2 57.2 Columbus OH WTTE-3 28.3 Dallas-Ft. Worth TX KTXD 47.1 Dallas-Ft. Worth TX KPFW LD-4 18.4 Dayton OH WKEF-2 22.2 Denver CO KTFD-3 50.3 Des Moines-Ames IA KCYM LD-4 45.4 Dutchess, Ulster, Orange, Westchester, Columbia, Sullivan, Fairfield Counties NY WRNN-2 48.2 El Paso TX KFOX-4 14.4 Flint MI WSMH-4 66.4 Fresno CA KMPH-4 26.4 Ft. Smith-Fay-Sprngdl-Rgrs AR KAJL LD-1 16.1 Green Bay WI WCWF-4 14.4 Greensboro-H.Point-W.Salem NC WXLV-2 45.2 Greenville-New Bern-Washington NC WYDO-4 14.4 Greenville-Spartanburg-Asheville SC WLOS-4 13.4 Harlingen-Weslaco-Brownsville-McAllen TX KTFV-4 32.4 Hartford-New Haven (extends into Springfield, MA) CT WCCT-4 20.4 Houston TX KEHO LD-5 32.5 Idaho Falls-Pocatillo ID KPIF-4 15.4 Indianapolis IN WSDI LD-6 30.6 Jacksonville FL WRCZ LD-2 35.2 Kansas City MO KCMN LD-4 42.4 Lafayette LA KXKW-1 32.1 Laredo TX KLDO-4 27.4 -

Broadcasting Telecasting

YEAR 101RN NOSI1)6 COLLEIih 26TH LIBRARY énoux CITY IOWA BROADCASTING TELECASTING THE BUSINESSWEEKLY OF RADIO AND TELEVISION APRIL 1, 1957 350 PER COPY c < .$'- Ki Ti3dddSIA3N Military zeros in on vhf channels 2 -6 Page 31 e&ol 9 A3I3 It's time to talk money with ASCAP again Page 42 'mars :.IE.iC! I ri Government sues Loew's for block booking Page 46 a2aTioO aFiE$r:i:;ao3 NARTB previews: What's on tap in Chicago Page 79 P N PO NT POW E R GETS BEST R E SULTS Radio Station W -I -T -H "pin point power" is tailor -made to blanket Baltimore's 15 -mile radius at low, low rates -with no waste coverage. W -I -T -H reaches 74% * of all Baltimore homes every week -delivers more listeners per dollar than any competitor. That's why we have twice as many advertisers as any competitor. That's why we're sure to hit the sales "bull's -eye" for you, too. 'Cumulative Pulse Audience Survey Buy Tom Tinsley President R. C. Embry Vice Pres. C O I N I F I I D E I N I C E National Representatives: Select Station Representatives in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington. Forloe & Co. in Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta. RELAX and PLAY on a Remleee4#01%,/ You fly to Bermuda In less than 4 hours! FACELIFT FOR STATION WHTN-TV rebuilding to keep pace with the increasing importance of Central Ohio Valley . expanding to serve the needs of America's fastest growing industrial area better! Draw on this Powerhouse When OPERATION 'FACELIFT is completed this Spring, Station WNTN -TV's 316,000 watts will pour out of an antenna of Facts for your Slogan: 1000 feet above the average terrain! This means . -

PBS and the Young Adult Viewer Tamara Cherisse John [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-12-2012 PBS and the Young Adult Viewer Tamara Cherisse John [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation John, Tamara Cherisse, "PBS and the Young Adult Viewer" (2012). Research Papers. Paper 218. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/218 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PBS AND THE YOUNG ADULT VIEWER by Tamara John B.A., Radio-Television, Southern Illinois University, 2010 B.A., Spanish, Southern Illinois University, 2010 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2012 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL PBS AND THE YOUNG ADULT VIEWER By Tamara John A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Professional Media and Media Management Approved by: Dr. Paul Torre, Chair Dr. Beverly Love Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale March 28, 2012 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF Tamara John, for the Master of Science degree in Professional Media and Media Management, presented on March 28, 2012, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: PBS AND THE YOUNG ADULT VIEWER MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Paul Torre Attracting and retaining teenage and young adult viewers has been a major challenge for most broadcasters. -

Sinclair Broadcast Group / Tammy Dupuy

SINCLAIR BROADCAST GROUP / TAMMY DUPUY 175 198 194 195 203 170 197 128 201 DR. OZ 3RD QUEEN QUEEN SEINFELD 4TH SEINFELD 5TH DR. OZ CYCLE LATIFAH LATIFAH MIND OF A MAN CYCLE CYCLE KING 2nd Cycle KING 3rd Cycle RANK MARKET %US STATION 2011-2014 2014-2015 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 4th Cycle 5th Cycle 2nd Cycle 3rd Cycle 8 WASHINGTON (HAGERSTOWN) DC 2.08% NEWS8/WJLA WTTG WDCA/WTTG WJLA WJLA WDCW WDCW WJAL 13 SEATTLE-TACOMA WA 1.60% KOMO/KOMO-DT2 KOMO/KOMO-DT2 KONG KSTW KSTW KSTW KSTW KSTW KSTW 23 PITTSBURGH PA 1.02% WPGH/WPMY WTAE WTAE KDKA/WPCW KDKA/WPCW WPGH/WPMY WPGH/WPMY KDKA/WPCW KDKA/WPCW 27 BALTIMORE MD 0.95% WBFF/WNUV/WUTB WBAL WBAL WBFF/WNUV/WUTB WBFF/WNUV/WUTB WBFF/WNUV/WUTB WBFF/WNUV WBFF/WNUV 32 COLUMBUS OH 0.80% WSYX/WTTE/WWHO WBNS WBNS WSYX/WTTE WSYX/WTTE WSYX/WTTE WSYX/WTTE W23BZ 35 CINCINNATI OH 0.78% EKRC/WKRC/WSTR WLWT WLWT WLWT WKRC/WSTR EKRC/WKRC EKRC/WKRC/WSTR WXIX WXIX 38 WEST PALM BEACH-FT PIERCE FL 0.70% WPEC/WTCN/WTVX WPBF WPBF WPTV WPTV WFLX WFLX WTCN/WTVX 43 HARRISBURG-LANCASTER-LEBANON-YORK PA 0.63% EHP/ELYH/WHP/WLYH WGAL WGAL WHP WHP WPMT WPMT WHP/WLYH 44 BIRMINGHAM (ANNISTON-TUSCALOOSA) AL 0.62% WABM/WBMA/WTTO WBMA WBMA WBRC WBRC WABM/WTTO WABM/WTTO WABM/WTTO 45 NORFOLK-PORTSMOUTH-NEWPORT NEWS VA 0.62% WTVZ WVEC WVEC WAVY/WVBT WAVY/WVBT WTVZ WTVZ WSKY WSKY 46 GREENSBORO-HIGH POINT-WINSTON SALEM NC 0.61% WMYV/WXLV WXII WXII WMYV/WXLV WMYV/WXLV WGHP WGHP WCWG WCWG 52 BUFFALO NY 0.55% WNYO/WUTV WIVB/WNLO WIVB WKBW WKBW WNYO/WUTV WNYO/WUTV 57 RICHMOND-PETERSBURG VA 0.48% WRLH/WRLH-DT WTVR WRIC WUPV/WWBT WUPV/WWBT