Ever Since Darwin Reflections Iii Natural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paradox of Genius Recognition That, Although Nature Surely

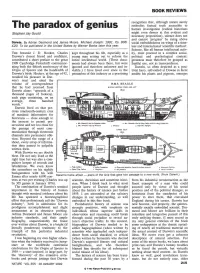

BOOK REVIEWS recognition that, although nature surely embodies factual truth accessible to The paradox of genius human investigation (radical historians Stephen Jay Gould might even demur at this evident and necessary proposition), science does not and cannot 'progress' by rising above Darwin. By Adrian Desmond and James Moore. Michael Joseph: 1991. Pp. 808. social embeddedness on wings of a time £20. To be published in the United States by Warner Books later this year. less and international 'scientific method'. Science, like all human intellectual activ THE botanist J. D. Hooker, Charles kept throughout his life, especially as a ity, must proceed in a complex social, Darwin's closest friend and confidant, young man setting out to reform the political and psychological context: contributed a short preface to the great entire intellectual world. (These docu greatness must therefore be grasped as 1909 Cambridge Festschrift commemor ments had always been there, but were fruitful use, not as transcendence. ating both the fiftieth anniversary of the ignored and therefore unknown and in Darwin, so often depicted as a posi Origin of Species and the hundredth of visible.) I have lived ever since in the tivist hero, self-exiled at Downe in Kent Darwin's birth. Hooker, at the age of 92, penumbra of this industry as a practising amidst his plants and pigeons, emerges recalled his pleasure in Dar- win's trust and cited the volume of correspondence H.M.S. BEAGLE that he had received from MIDDLE SECTION FORE AND AFT Darwin alone: "upwards of a thousand pages of foolscap, each page containing, on an average, three hundred words." Darwin lived on that pre cious nineteenth-century crux of maximal information for historians - close enough to the present to permit pre r. -

THE NAKED APE By

THE NAKED APE by Desmond Morris A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Jonathan Cape Ltd. PRINTING HISTORY Jonathan Cape edition published October 1967 Serialized in THE SUNDAY MIRROR October 1967 Literary Guild edition published April 1969 Transrvorld Publishers edition published May 1969 Bantam edition published January 1969 2nd printing ...... January 1969 3rd printing ...... January 1969 4th printing ...... February 1969 5th printing ...... June1969 6th printing ...... August 1969 7th printing ...... October 1969 8th printing ...... October 1970 All rights reserved. Copyright (C 1967 by Desmond Morris. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mitneograph or any other means, without permission. For information address: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 30 Bedford Square, London Idi.C.1, England. Bantam Books are published in Canada by Bantam Books of Canada Ltd., registered user of the trademarks con silting of the word Bantam and the portrayal of a bantam. PRINTED IN CANADA Bantam Books of Canada Ltd. 888 DuPont Street, Toronto .9, Ontario CONTENTS INTRODUCTION, 9 ORIGINS, 13 SEX, 45 REARING, 91 EXPLORATION, 113 FIGHTING, 128 FEEDING, 164 COMFORT, 174 ANIMALS, 189 APPENDIX: LITERATURE, 212 BIBLIOGRAPHY, 215 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is intended for a general audience and authorities have therefore not been quoted in the text. To do so would have broken the flow of words and is a practice suitable only for a more technical work. But many brilliantly original papers and books have been referred to during the assembly of this volume and it would be wrong to present it without acknowledging their valuable assistance. At the end of the book I have included a chapter-by-chapter appendix relating the topics discussed to the major authorities concerned. -

Human Origins

HUMAN ORIGINS Methodology and History in Anthropology Series Editors: David Parkin, Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford David Gellner, Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford Volume 1 Volume 17 Marcel Mauss: A Centenary Tribute Learning Religion: Anthropological Approaches Edited by Wendy James and N.J. Allen Edited by David Berliner and Ramon Sarró Volume 2 Volume 18 Franz Baerman Steiner: Selected Writings Ways of Knowing: New Approaches in the Anthropology of Volume I: Taboo, Truth and Religion. Knowledge and Learning Franz B. Steiner Edited by Mark Harris Edited by Jeremy Adler and Richard Fardon Volume 19 Volume 3 Difficult Folk? A Political History of Social Anthropology Franz Baerman Steiner. Selected Writings By David Mills Volume II: Orientpolitik, Value, and Civilisation. Volume 20 Franz B. Steiner Human Nature as Capacity: Transcending Discourse and Edited by Jeremy Adler and Richard Fardon Classification Volume 4 Edited by Nigel Rapport The Problem of Context Volume 21 Edited by Roy Dilley The Life of Property: House, Family and Inheritance in Volume 5 Béarn, South-West France Religion in English Everyday Life By Timothy Jenkins By Timothy Jenkins Volume 22 Volume 6 Out of the Study and Into the Field: Ethnographic Theory Hunting the Gatherers: Ethnographic Collectors, Agents and Practice in French Anthropology and Agency in Melanesia, 1870s–1930s Edited by Robert Parkin and Anna de Sales Edited by Michael O’Hanlon and Robert L. Welsh Volume 23 Volume 7 The Scope of Anthropology: Maurice Godelier’s Work in Anthropologists in a Wider World: Essays on Field Context Research Edited by Laurent Dousset and Serge Tcherkézoff Edited by Paul Dresch, Wendy James, and David Parkin Volume 24 Volume 8 Anyone: The Cosmopolitan Subject of Anthropology Categories and Classifications: Maussian Reflections on By Nigel Rapport the Social Volume 25 By N.J. -

The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould

Punctuated Equilibria: The Tempo and Mode of Evolution Reconsidered Stephen Jay Gould; Niles Eldredge Paleobiology, Vol. 3, No. 2. (Spring, 1977), pp. 115-151. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0094-8373%28197721%293%3A2%3C115%3APETTAM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H Paleobiology is currently published by Paleontological Society. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/paleo.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Aug 19 19:30:53 2007 Paleobiology. -

Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(S): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S

Paleontological Society Exaptation-A Missing Term in the Science of Form Author(s): Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba Reviewed work(s): Source: Paleobiology, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Winter, 1982), pp. 4-15 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2400563 . Accessed: 27/08/2012 17:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Paleontological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Paleobiology. http://www.jstor.org Paleobiology,8(1), 1982, pp. 4-15 Exaptation-a missing term in the science of form StephenJay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba* Abstract.-Adaptationhas been definedand recognizedby two differentcriteria: historical genesis (fea- turesbuilt by naturalselection for their present role) and currentutility (features now enhancingfitness no matterhow theyarose). Biologistshave oftenfailed to recognizethe potentialconfusion between these differentdefinitions because we have tendedto view naturalselection as so dominantamong evolutionary mechanismsthat historical process and currentproduct become one. Yet if manyfeatures of organisms are non-adapted,but available foruseful cooptation in descendants,then an importantconcept has no name in our lexicon (and unnamed ideas generallyremain unconsidered):features that now enhance fitnessbut were not built by naturalselection for their current role. -

Darwin's Middle Road∗

Stephen Jay Gould DARWIN'S MIDDLE ROAD∗ "We began to sail up the narrow strait lamenting," narrates Odysseus. "For on the one hand lay Scylla, with twelve feet all dangling down; and six necks exceeding long, and on each a hideous head, and therein three rows of teeth set thick and close, full of black death. And on the other mighty Charybdis sucked down the salt sea water. As often as she belched it forth, like a cauldron on a great fire she would seethe up through all her troubled deeps." Odysseus managed to swerve around Charybdis, but Scylla grabbed six of his finest men and devoured them in his sight-"the most pitiful thing mine eyes have seen of all my travail in searching out the paths of the sea." False lures and dangers often come in pairs in our legends and metaphors—consider the frying pan and the fire, or the devil and the deep blue sea. Prescriptions for avoidance either emphasize a dogged steadiness—the straight and narrow of Christian evangelists—or an averaging between unpleasant alternatives—the golden mean of Aristotle. The idea1 of steering a course between undesirable extremes emerges as a central prescription for a sensible life. The nature of scientific creativity is both a perennial topic of discussion and a prime candidate for seeking a golden mean. The two extreme positions have not been directly competing for allegiance of the unwary. They have, rather, replaced each other sequentially, with one now in the ascendancy, the other eclipsed. The first—inductivism—held that great scientists are primarily great observers and patient accumulators of information. -

Full Text (PDF)

International Journal of Art and Art History December 2014, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 35-65 ISSN: 2374-2321 (Print), 2374-233X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijaah.v2n2a2 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v2n2a2 A Historiographical Discussion on the Origins of Visual Art Aaron Lawler1 Abstract The purpose of this research is to identify a correlation between biological (materialist) origins and adaptations to the creation and appreciation of art, specifically through the development of the aesthetic sense. Most research in the historiography of art and the origins of visual art, come from a purely philosophical tradition. Here, the focus is on scientific historiography in conjunction with philosophy, as a lens for understanding evolutionary biological adaptation. Premise This discourse, concerning the origins of the fine arts (and more specifically the visual arts), is explored through Darwinian evolution and inherited traits. Using a primarily materialist philosophical ontology, and a scientific epistemology, I hope to explain art history from a biological historiography. In this discourse, I will not propose a sole hereditary origin for the visual arts, but allow for a view that is also not solely anthropologically and/or sociologically driven. In other words, the creation and study of the visual arts, need not be originated in only as a social construct or cultural product, but might also be a genetically, materially originated function of the human as a material entity. 1Senior Lecturer and Adjunct Faculty Mentor, Moser College - Benedictine University, USA. Phone: 630-220-9565 36 International Journal of Art and Art History, Vol. -

The Evolution of Darwinian Sexualities

BJHS Themes (2021), 1–23 doi:10.1017/bjt.2021.7 RESEARCH ARTICLE The evolution of Darwinian sexualities Erika Lorraine Milam* History Department, Princeton University *Corresponding author: Erika Milam, Email: [email protected] Abstract Charles Darwin’s Descent of Man was suffused with questions of courtship, mating and sex. Following in his footsteps, biologists throughout the twentieth century interrogated the sexual behaviour of humans and animals. This paper charts the fate of evolutionary theories of sexuality to argue that – despite legal and social gains of the past century – when biologists used sexual selection as a tool for theorizing the evolution of homosexual behaviour (which happened only rarely), the effect of their theories was to continuously reinscribe normative heterosexuality. If, at the end of the nineteenth century, certain sex theorists viewed homosexuality as a marker of intermediate sex, by the late twentieth a new generation of evolutionary theorists idealized gay men as hyper- masculine biological males whose sexual behaviours were uncompromised by the necessity of accommodating women’s sexual preferences. In both cases, normative assumptions about gender were interwoven with those about sexuality. By the twenty-first century, animal exemplars were again mobilized alongside data gathered about human sexual practices in defence of gay rights, but this time by creating the opportunity for naturalization without recourse to biological determinism. Charles Darwin’s Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex was suffused with questions of courtship, mating and sex.1 Darwin’s reconstruction of animal history positioned ani- mals as vital sources of information on the development of the sexes and the mechanisms of courtship. -

The Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography and Stephen Jay Gould Author(S): Stephen P

The neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography and Stephen Jay Gould Author(s): Stephen P. Hubbell Source: Paleobiology, 31(sp5):122-132. 2005. Published By: The Paleontological Society DOI: 10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0122:TNTOBA]2.0.CO;2 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1666/0094- 8373%282005%29031%5B0122%3ATNTOBA%5D2.0.CO%3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Paleobiology,31(2, Supplement),2005,pp.122±132 The neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography and Stephen Jay Gould Stephen P. Hubbell Abstract.ÐNeutral theory in ecology is based on the symmetry assumption that ecologically similar species in a community can be treated as demographically equivalent on a per capita basisÐequiv- alent in birth and death rates, in rates of dispersal, and even in the probability of speciating. Al- though only a ®rst approximation, the symmetry assumption allows the development of a quan- titative neutral theory of relative species abundance and dynamic null hypotheses for the assembly of communities in ecological time and for phylogeny and phylogeography in evolutionary time. -

![THE USE of EVOLUTION in EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY] Evolutionary Psychology Is a New Research Field That Studies Behaviour](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5326/the-use-of-evolution-in-evolutionary-psychology-evolutionary-psychology-is-a-new-research-field-that-studies-behaviour-2245326.webp)

THE USE of EVOLUTION in EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY] Evolutionary Psychology Is a New Research Field That Studies Behaviour

2012 Utrecht University B.M.T. Stel [THE USE OF EVOLUTION IN EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY] Evolutionary Psychology is a new research field that studies behaviour. In their efforts they try to explain human behaviour and social organization different methods and theories are used. But not all these methods and theories are accepted by scientists. Problems can be identified in the use of these methods and in the formulation of theories. This results in a discussion that questions the validity of the explanations and hypotheses formulated by Evolutionary Psychology Content Introduction 3 Aim thesis 3 Chapter 1 Founders of the study of instincts and behaviour 4 1.1 Darwin and the expression of emotions 4 1.2 Wundt and the foundation of experimental psychology 6 Chapter 2 Research on the evolution of behavioural traits 9 2.1 Romanes on animal psychology 9 2.2 Three new perspectives on the behavioural traits 11 2.2.1 Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen and the rise of Ethology 11 2.2.2 Jacques Loeb on the theory of Tropism 15 2.2.3 Animal psychology by Bierens de Haan 17 2.3 Sociobiology as the new synthesis 18 2.3.1 Edward O. Wilson 18 2.3.2 Desmond Morris and the use of sociobiology 22 Chapter 3 Evolutionary Psychology, a new research field 25 3.1 Aims of Evolutionary Psychology 25 3.2 Important theories in evolutionary psychology 26 3.2.1 The massive Modularity Thesis 26 3.2.2 The Monomorphic Mind Thesis 27 3.3 The reliability of results, a criticism on evolutionary psychology 27 3.3.1. -

Creatures of Cain

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Human nature contains the seeds of humanity’s destruction. Or so it seemed to popular consumers of evolutionary theory in the late 1960s who maintained that the essential quality distinguishing the human animal from its simian kin lay in our capacity for murder. This startlingly pessimistic view enjoyed wide currency in the United States between 1966 and 1975 and be- came known, by its critics, as the killer ape theory. Readers at the time associated the concept of humans as mere animals with three men. Robert Ardrey published The Territorial Imperative in 1966, which leapt off bookshelves across the country. He styled himself an amateur scien- tist and believed his experience as a playwright gave him unique insights into the composition of human nature. Konrad Lorenz’s white- maned visage loaned him a distinguished appearance despite the black rubber boots he fa- vored when showing people around his farm. Lorenz, the author of On Aggres- sion, which appeared in English translation the same year as Ardrey’s Territo- rial Imperative, would later share the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his perceptive contributions to the scientific study of animal behavior. Desmond Morris unknowingly capitalized on the success of both authors when he published The Naked Ape the following year. Well known as the host of Granada TV’s popular Zootime program, based out of the London Zoo, Morris soon gave up scientific work to concentrate on writing scientific non- fiction and refining his surrealist painting. -

Opus 200 - Stephen Jay Gould

Opus 200 - Stephen Jay Gould Natural History, August 1991, 100 (8):12-18 In my adopted home of Puritan New England, I have learned that personal indulgence is a vice to be tolerated only at rare intervals. Combine this stricture with two further principles and this essay achieves its rationale: first, that we celebrate in hundreds and their easy multiples (the Columbian quincentenary and the fiftieth anniversary of DiMaggio's hitting streak—both about equally important, and only the latter an unambiguous good); second, that geologists learn to take the long view. This is my 200th essay in "This View of Life," a series begun in January 1974 (with never an issue missed). If once is an incident and twice a tradition, I now establish an indulgence for even multiples of 100 only. Essays must express the personal thoughts and prejudices of authors—for this has been the genre's definition ever since Montaigne. But I have tried not to abuse the bully pulpit of this forum to act as a shill for my own professional research and theorizing. Still, once in a hundred shouldn't subvert my bonae fides, so I indulge, as I did once before at my own centenary. Essay 100 treated the Bahamian land snails that usurp the bulk of my time for empirical research. Opus 200 shall discuss the theoretical idea most central to my work— punctuated equilibrium. Moreover, Niles Eldredge and I formulated the theory of punctuated equilibrium in 1971, and I can scarcely resist the double whammy of 200 essays on the twentieth anniversary of "punk eke," the affectionate nickname used by supporters, while detractors have parried with "evolution by jerks." Punctuated equilibrium began, as so much else that later looms large in our lives, as a little path that might never have opened.