Northern Expedition: China's Arctic Ambition and Activism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soyuz TMA-11 / Expedition 16 Manuel De La Mission

Soyuz TMA-11 / Expedition 16 Manuel de la mission SOYUZ TMA-11 – EXPEDITION 16 Par Philippe VOLVERT SOMMAIRE I. Présentation des équipages II. Présentation de la mission III. Présentation du vaisseau Soyuz IV. Précédents équipages de l’ISS V. Chronologie de lancement VI. Procédures d’amarrage VII. Procédures de retour VIII. Horaires IX. Sources A noter que toutes les heures présentes dans ce dossier sont en heure GMT. I. PRESENTATION DES EQUIPAGES Equipage Expedition 15 Fyodor YURCHIKHIN (commandant ISS) Lieu et Lieu et date de naissance : 03/01/1959 ; Batumi (Géorgie) Statut familial : Marié et 2 enfants Etudes : Graduat d’économie à la Moscow Service State University Statut professionnel: Ingénieur et travaille depuis 1993 chez RKKE Roskosmos : Sélectionné le 28/07/1997 (RKKE-13) Précédents vols : STS-112 (07/10/2002 au 18/10/2002), totalisant 10 jours 19h58 Oleg KOTOV(ingénieur de bord) Lieu et date de naissance : 27/10/1965 ; Simferopol (Ukraine) Statut familial : Marié et 2 enfants Etudes : Doctorat en médecine obtenu à la Sergei M. Kirov Military Medicine Academy Statut professionnel: Colonel, Russian Air Force et travaille au centre d’entraînement des cosmonautes, le TsPK Roskosmos : Sélectionné le 09/02/1996 (RKKE-12) Précédents vols : - Clayton Conrad ANDERSON (Ingénieur de vol ISS) Lieu et date de naissance : 23/02/1959 ; Omaha (Nebraska) Statut familial : Marié et 2 enfants Etudes : Promu bachelier en physique à Hastings College, maîtrise en ingénierie aérospatiale à la Iowa State University Statut professionnel: Directeur du centre des opérations de secours à la Nasa Nasa : Sélectionné le 04/06/1998 (Groupe) Précédents vols : - Equipage Expedition 16 / Soyuz TM-11 Peggy A. -

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Imagining a Universal Empire: a Study of the Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions Attributed to Li Gonglin

Journal of chinese humanities 5 (2019) 124-148 brill.com/joch Imagining a Universal Empire: a Study of the Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions Attributed to Li Gonglin Ge Zhaoguang 葛兆光 Professor of History, Fudan University, China [email protected] Abstract This article is not concerned with the history of aesthetics but, rather, is an exercise in intellectual history. “Illustrations of Tributary States” [Zhigong tu 職貢圖] as a type of art reveals a Chinese tradition of artistic representations of foreign emissaries paying tribute at the imperial court. This tradition is usually seen as going back to the “Illustrations of Tributary States,” painted by Emperor Yuan in the Liang dynasty 梁元帝 [r. 552-554] in the first half of the sixth century. This series of paintings not only had a lasting influence on aesthetic history but also gave rise to a highly distinctive intellectual tradition in the development of Chinese thought: images of foreign emis- saries were used to convey the Celestial Empire’s sense of pride and self-confidence, with representations of strange customs from foreign countries serving as a foil for the image of China as a radiant universal empire at the center of the world. The tra- dition of “Illustrations of Tributary States” was still very much alive during the time of the Song dynasty [960-1279], when China had to compete with equally powerful neighboring states, the empire’s territory had been significantly diminished, and the Chinese population had become ethnically more homogeneous. In this article, the “Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions” [Wanfang zhigong tu 萬方職貢圖] attributed to Li Gonglin 李公麟 [ca. -

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals Wang Hongxing Key words: Chu Capitals Danyang Ying Chenying Shouying According to accurate historical documents, the capi- In view of the recent research on the civilization pro- tals of Chu State include Danyang 丹阳 of the early stage, cess of the middle reach of Yangtze River, we may infer Ying 郢 of the middle stage and Chenying 陈郢 and that Danyang ought to be a central settlement among a Shouying 寿郢 of the late stage. Archaeologically group of settlements not far away from Jingshan 荆山 speaking, Chenying and Shouying are traceable while with rice as the main crop. No matter whether there are the locations of Danyang and Yingdu 郢都 are still any remains of fosses around the central settlement, its oblivious and scholars differ on this issue. Since Chu area must be larger than ordinary sites and be of higher capitals are the political, economical and cultural cen- scale and have public amenities such as large buildings ters of Chu State, the research on Chu capitals directly or altars. The site ought to have definite functional sec- affects further study of Chu culture. tions and the cemetery ought to be divided into that of Based on previous research, I intend to summarize the aristocracy and the plebeians. The relevant docu- the exploration of Danyang, Yingdu and Shouying in ments and the unearthed inscriptions on tortoise shells recent years, review the insufficiency of the former re- from Zhouyuan 周原 saying “the viscount of Chu search and current methods and advance some personal (actually the ruler of Chu) came to inform” indicate that opinion on the locations of Chu capitals and later explo- Zhou had frequent contact and exchange with Chu. -

New Siberian Islands Archipelago)

Detrital zircon ages and provenance of the Upper Paleozoic successions of Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Islands archipelago) Victoria B. Ershova1,*, Andrei V. Prokopiev2, Andrei K. Khudoley1, Nikolay N. Sobolev3, and Eugeny O. Petrov3 1INSTITUTE OF EARTH SCIENCE, ST. PETERSBURG STATE UNIVERSITY, UNIVERSITETSKAYA NAB. 7/9, ST. PETERSBURG 199034, RUSSIA 2DIAMOND AND PRECIOUS METAL GEOLOGY INSTITUTE, SIBERIAN BRANCH, RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, LENIN PROSPECT 39, YAKUTSK 677980, RUSSIA 3RUSSIAN GEOLOGICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE (VSEGEI), SREDNIY PROSPECT 74, ST. PETERSBURG 199106, RUSSIA ABSTRACT Plate-tectonic models for the Paleozoic evolution of the Arctic are numerous and diverse. Our detrital zircon provenance study of Upper Paleozoic sandstones from Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Island archipelago) provides new data on the provenance of clastic sediments and crustal affinity of the New Siberian Islands. Upper Devonian–Lower Carboniferous deposits yield detrital zircon populations that are consistent with the age of magmatic and metamorphic rocks within the Grenvillian-Sveconorwegian, Timanian, and Caledonian orogenic belts, but not with the Siberian craton. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test reveals a strong similarity between detrital zircon populations within Devonian–Permian clastics of the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island (and possibly Chukotka), and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago. These results suggest that the New Siberian Islands, along with Wrangel Island and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago, were located along the northern margin of Laurentia-Baltica in the Late Devonian–Mississippian and possibly made up a single tectonic block. Detrital zircon populations from the Permian clastics record a dramatic shift to a Uralian provenance. The data and results presented here provide vital information to aid Paleozoic tectonic reconstructions of the Arctic region prior to opening of the Mesozoic oceanic basins. -

IAF-01-T.1.O1 Progress on the International Space Station

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20150020985 2019-08-31T05:38:38+00:00Z IAF-01-T.1.O1 Progress on the International Space Station - We're Part Way up the Mountain John-David F. Bartoe and Thomas Holloway NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, USA The first phase of the International Space Station construction has been completed, and research has begun. Russian, U.S., and Canadian hardware is on orbit, ard Italian logistics modules have visited often. With the delivery of the U.S. Laboratory, Destiny, significant research capability is in place, and dozens of U.S. and Russian experiments have been conducted. Crew members have been on orbit continuously since November 2000. Several "bumps in the road" have occurred along the way, and each has been systematically overcome. Enormous amounts of hardware and software are being developed by the International Space Station partners and participants around the world and are largely on schedule for launch. Significant progress has been made in the testing of completed elements at launch sites in the United States and Kazakhstan. Over 250,000 kg of flight hardware have been delivered to the Kennedy Space Center and integrated testing of several elements wired together has progressed extremely well. Mission control centers are fully functioning in Houston, Moscow, and Canada, and operations centers Darmstadt, Tsukuba, Turino, and Huntsville will be going on line as they are required. Extensive coordination efforts continue among the space agencies of the five partners and two participants, involving 16 nations. All of them continue to face their own challenges and have achieved significant successes. -

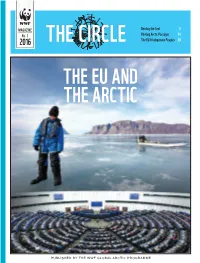

The Eu and the Arctic

MAGAZINE Dealing the Seal 8 No. 1 Piloting Arctic Passages 14 2016 THE CIRCLE The EU & Indigenous Peoples 20 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC PUBLISHED BY THE WWF GLOBAL ARCTIC PROGRAMME TheCircle0116.indd 1 25.02.2016 10.53 THE CIRCLE 1.2016 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC Contents EDITORIAL Leaving a legacy 3 IN BRIEF 4 ALYSON BAILES What does the EU want, what can it offer? 6 DIANA WALLIS Dealing the seal 8 ROBIN TEVERSON ‘High time’ EU gets observer status: UK 10 ADAM STEPIEN A call for a two-tier EU policy 12 MARIA DELIGIANNI Piloting the Arctic Passages 14 TIMO KOIVUROVA Finland: wearing two hats 16 Greenland – walking the middle path 18 FERNANDO GARCES DE LOS FAYOS The European Parliament & EU Arctic policy 19 CHRISTINA HENRIKSEN The EU and Arctic Indigenous peoples 20 NICOLE BIEBOW A driving force: The EU & polar research 22 THE PICTURE 24 The Circle is published quar- Publisher: Editor in Chief: Clive Tesar, COVER: terly by the WWF Global Arctic WWF Global Arctic Programme [email protected] (Top:) Local on sea ice in Uumman- Programme. Reproduction and 8th floor, 275 Slater St., Ottawa, naq, Greenland. quotation with appropriate credit ON, Canada K1P 5H9. Managing Editor: Becky Rynor, Photo: Lawrence Hislop, www.grida.no are encouraged. Articles by non- Tel: +1 613-232-8706 [email protected] (Bottom:) European Parliament, affiliated sources do not neces- Fax: +1 613-232-4181 Strasbourg, France. sarily reflect the views or policies Design and production: Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commonss of WWF. Send change of address Internet: www.panda.org/arctic Film & Form/Ketill Berger, and subscription queries to the [email protected] ABOVE: Sarek glacier, Sarek National address on the right. -

Expedition 16 Adding International Science

EXPEDITION 16 ADDING INTERNATIONAL SCIENCE The most complex phase of assembly since the NASA Astronaut Peggy Whitson, the fi rst woman Two days after launch, International Space Station was fi rst occupied seven commander of the ISS, and Russian Cosmonaut the Soyuz docked The International Space Station is seen by the crew of STS-118 years ago began when the Expedition 16 crew arrived Yuri Malenchenko were launched aboard the Soyuz to the Space Station as Space Shuttle Endeavour moves away. at the orbiting outpost. During this ambitious six-month TMA-11 spacecraft from the Baikonur Cosmodrome joining Expedition 15 endeavor, an unprecedented three Space Shuttle in Kazakhstan on October 10. The two veterans of Commander Fyodor crews will visit the Station delivering critical new earlier missions aboard the ISS were accompanied by Yurchikhin, Oleg Kotov, components – the American-built “Harmony” node, the Dr. Sheikh Muzaphar Shukor, an orthopedic surgeon both of Russia, and European Space Agency’s “Columbus” laboratory and and the fi rst Malaysian to fl y in space. NASA Flight Engineer Japanese “Kibo” element. Clayton Anderson. Shukor spent nine days CREW PROFILE on the ISS, returning to Earth in the Soyuz Peggy Whitson (Ph. D.) TMA-10 on October Expedition 16 Commander 21 with Yurchikhin and Born: February 9, 1960, Mount Ayr, Iowa Kotov who had been Education: Graduated with a bachelors degree in biology/chemistry from Iowa aboard the station since Wesleyan College, 1981 & a doctorate in biochemistry from Rice University, 1985 April 9. Experience: Selected as an astronaut in 1996, Whitson served as a Science Offi cer during Expedition 5. -

Icebreaker Booklet

Ideas... Students as Partners: Peer Support Icebreakers Produced by: Teaching,Students Learning as and Partners, Support Office 2 Peer Support Icebreakers Peer Support Icebreakers 31 . Who Is This For? as.. Ide This booklet will come in handy for any group facilitator, but has been primarily designed for use by PASS Leaders, Mentors and Students as Partners staff. Too often we see the same old ice-breakers and energizers used at training courses/first meetings; the aim of this booklet is to provide you with introductory activities that you might not have used or taken part in before! This booklet is an on-going publication– if you have an icebreaker that you think should be included then send an email with your ideas to [email protected] so that future students can benefit from them! Why Use Icebreakers? Icebreakers are discussion questions or activities used to help participants relax and ease people into a group meeting or learning situation. They are great for learning each other's names and personal/professional information. Icebreakers: • create a positive group atmosphere • help people to relax • break down social barriers • energize & motivate • help people to think outside the box • help people to get to know one another Whether it is a small get together or a large training session, we all want to feel that we share some common ground with our fellow participants. By creating a warm and friendly personal learning environment, the attendees will participate and learn more. Be creative and design your own variations on the ice breakers you find here. -

NASA Process for Limiting Orbital Debris

NASA-HANDBOOK NASA HANDBOOK 8719.14 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Approved: 2008-07-30 Washington, DC 20546 Expiration Date: 2013-07-30 HANDBOOK FOR LIMITING ORBITAL DEBRIS Measurement System Identification: Metric APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE – DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED NASA-Handbook 8719.14 This page intentionally left blank. Page 2 of 174 NASA-Handbook 8719.14 DOCUMENT HISTORY LOG Status Document Approval Date Description Revision Baseline 2008-07-30 Initial Release Page 3 of 174 NASA-Handbook 8719.14 This page intentionally left blank. Page 4 of 174 NASA-Handbook 8719.14 This page intentionally left blank. Page 6 of 174 NASA-Handbook 8719.14 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 SCOPE...........................................................................................................................13 1.1 Purpose................................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Applicability ....................................................................................................................... 13 2 APPLICABLE AND REFERENCE DOCUMENTS................................................14 3 ACRONYMS AND DEFINITIONS ...........................................................................15 3.1 Acronyms............................................................................................................................ 15 3.2 Definitions ......................................................................................................................... -

Post Increment Evaluation Report Increment 11 International Space

SSP 54311 Baseline WWW.NASAWATCH.COM Post Increment Evaluation Report Increment 11 International Space Station Program Baseline June 2006 National Aeronautics and Space Administration International Space Station Program Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas Contract Number: NNJ04AA02C WWW.NASAWATCH.COM SSP 54311 Baseline - WWW.NASAWATCH.COM REVISION AND HISTORY PAGE REV. DESCRIPTION PUB. DATE - Initial Release (Reference per SSCD XXXXXX, EFF. XX-XX-XX) XX-XX-XX WWW.NASAWATCH.COM SSP 54311 Baseline - WWW.NASAWATCH.COM INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION PROGRAM POST INCREMENT EVALUATION REPORT INCREMENT 11 CHANGE SHEET Month XX, XXXX Baseline Space Station Control Board Directive XXXXXX/(X-X), dated XX-XX-XX. (X) CHANGE INSTRUCTIONS SSP 54311, Post Increment Evaluation Report Increment 11, has been baselined by the authority of SSCD XXXXXX. All future updates to this document will be identified on this change sheet. WWW.NASAWATCH.COM SSP 54311 Baseline - WWW.NASAWATCH.COM INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION PROGRAM POST INCREMENT EVALUATION REPORT INCREMENT 11 Baseline (Reference SSCD XXXXXX, dated XX-XX-XX) LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES Month XX, XXXX The current status of all pages in this document is as shown below: Page Change No. SSCD No. Date i - ix Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX 1-1 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX 2-1 - 2-2 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX 3-1 - 3-3 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX 4-1 - 4-15 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX 5-1 - 5-10 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX 6-1 - 6-4 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX 7-1 - 7-61 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX A-1 - A-9 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX B-1 - B-3 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX C-1 - C-2 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX D-1 - D-92 Baseline XXXXXX Month XX, XXXX WWW.NASAWATCH.COM SSP 54311 Baseline - WWW.NASAWATCH.COM INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION PROGRAM POST INCREMENT EVALUATION REPORT INCREMENT 11 JUNE 2006 i SSP 54311 Baseline - WWW.NASAWATCH.COM SSCB APPROVAL NOTICE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION PROGRAM POST INCREMENT EVALUATION REPORT INCREMENT 11 JUNE 2006 Michael T. -

Expedition 8 MISSION OVERVIEW

Expedition 8 MISSION OVERVIEW To Improve Life Here, Science Comes to the Forefront To Extend Life to There, To Find Life Beyond. Experiments from earlier expeditions will Education Payload Operations (EPO) remain aboard the International Space include three educational activities that That is NASAs vision. Station (ISS), continuing to benefit from will focus on demonstrating science, long-term exposure to microgavity, and mathematics, technology, engineering or Michael Foale, additional studies in the life and physical geography principles. Expedition 8 Commander, NASA ISS sciences and space technology development Group Activation Packs -- YEAST will Science Officer: will be added. evaluate the role of individual genes in the When we look back fifty years to this time, we Most of the research complement for response of yeast to space flight conditions. wont remember the experiments that were Expedition 8 will be carried out with The results of this research could help performed, we wont remember the assembly scientific research facilities and samples clarify how mammalian cells grow under that was done, we may barely remember any already on board the Space Station. microgravity conditions and determine if individuals. What we will know was that countries Additional experiments are being evaluated genes are altered. came together to do the first joint international and prepared to take advantage of the Synchronized Position Hold, Engage, project, and we will know that that was the seed limited cargo space on the Soyuz or Reorient, Experimental Satellites that started us off to the moon and Mars. Progress vehicles. The research agenda for (SPHERES) will allow scientists to study the expedition remains flexible.