Livcd) Final Performance Evaluation Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

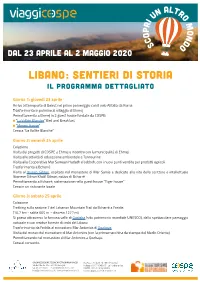

Viaggi Viaggi N O U I M

altr un o i m r viaggi o p n o d c o s altr viaggi viaggi un o i m r o p n o d c o s dal 23 aprile al 2 maggio 2020 Libano: sentieri di storia il programma dettagliato Giorno 1: giovedì 23 aprile Arrivo all’aeroporto di Beirut nel primo pomeriggio con il volo Alitalia da Roma Trasferimento in pulmino al villaggio di Ehmej Pernottamento a Ehmej in 2 guest house fondate da COSPE: “La Vallée Blanche” Bed and Breakfast “Mosaic House” Cena a “La Vallée Blanche” Giorno 2: venerdì 24 aprile Colazione Visita dei progetti di COSPE a Ehmej e incontro con la municipalità di Ehmej Visita alle attività di educazione ambientale a Tannourine Visita alla Cooperativa Mar Semaan Hadath el Jebbeh, con i nuovi punti vendita per prodotti agricoli Trasferimento a Bcharré Visita al museo Gibran, ospitato nel monastero di Mar Sarkis e dedicato alla vita dello scrittore e intellettuale libanese Gibran Khalil Gibran, nativo di Bcharré Pernottamento a Bcharré, sistemazione nella guest house “Tiger house” Cena in un ristorante locale Giorno 3: sabato 25 aprile Colazione Trekking sulla sezione 7 del Lebanon Mountain Trail da Bcharré a Freidis (10,7 km - salita 605 m – discesa 1277 m) Si passa attraverso la famosa valle di Qadisha (sito patrimonio mondiale UNESCO), dallo spettacolare paesaggio naturale e con residue foreste di cedri del Libano Trasferimento da Freidis al monastero Mar Antonios di Qozhaya Visita del museo del monastero di Mar Antonios (con la prima macchina da stampa del Medio Oriente) Pernottamento nel monastero di Mar Antonios a Qozhaya Cena al convento. -

Dissertation-Master-Cover Copy

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Conflict and Institution Building in Lebanon, 1946-1955 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/67x11827 Author Abu-Rish, Ziad Munif Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Conflict and Institution Building in Lebanon, 1946-1955 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Ziad Munif Abu-Rish 2014 © Copyright by Ziad Munif Abu-Rish 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTAITON Conflict and Institution Building in Lebanon, 1946-1955 by Ziad Munif Abu-Rish Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor James L. Gelvin, Chair This dissertation broadens the inquiry into the history of state formation, economic development, and popular mobilization in Lebanon during the early independence period. The project challenges narratives of Lebanese history and politics that are rooted in exceptionalist and deterministic assumptions. It does so through an exploration of the macro-level transformations of state institutions, the discourses and practices that underpinned such shifts, and the particular series of struggles around Sharikat Kahruba Lubnan that eventual led to the nationalization of the company. The dissertation highlights the ways in which state institutions during the first decade of independence featured a dramatic expansion in both their scope and reach vis-à-vis Lebanese citizens. Such shifts were very much shaped by the contexts of decolonization, the imperatives of regime consolidation, and the norms animating the post-World War II global and regional orders. -

Syria Refugee Response

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON, Bekaa & Baalbek-El Hermel Governorate Distribution of the Registered Syrian Refugees at the Cadastral Level As o f 3 0 Se p t e m b e r 2 0 2 0 Charbine El-Hermel BEKAA & Baalbek - El Hermel 49 Total No. of Household Registered 73,427 Total No. of Individuals Registered 340,600 Hermel 6,580 El Hermel Michaa Qaa Jouar Mrajhine Maqiye Qaa Ouadi Zighrine El-Khanzir 36 5 Hermel Deir Mar Jbab Maroun Baalbek 29 10 Qaa Baalbek 10,358 Qaa Baayoun 553 Ras Baalbek El Gharbi Ras Baalbek 44 Ouadi Faara Ras Baalbek Es-Sahel Ouadi 977 Faara Maaysra 4 El-Hermel 32 Halbata Ras Baalbek Ech-Charqi 1 Zabboud 116 Ouadi 63 Fekehe El-Aaoss 2,239 Kharayeb El-Hermel Harabta 16 Bajjaje Aain 63 7 Baalbek Sbouba 1,701 Nabha Nabi Ed-Damdoum Osmane 44 288 Aaynata Baalbek Laboue 34 1,525 Barqa Ram 29 Baalbek 5 Qarha Baalbek Moqraq Chaat Bechouat Aarsal 2,031 48 Riha 33,521 3 Yammoune 550 Deir Kneisset El-Ahmar Baalbek 3,381 28 Dar Btedaai Baalbak El-Ouassaa 166 30 Youmine 2,151 Maqne Chlifa Mazraat 260 beit 523 Bouday Mchaik Nahle 1,501 3 Iaat baalbek haouch 2,421 290 El-Dehab 42 Aadous Saaide 1,244 Hadath 1,406 Haouch Baalbek Jebaa Kfar Dane Haouche Tall Safiye Baalbek 656 375 Barada 12,722 478 466 Aamchki Taraiya Majdaloun 13 905 1,195 Douris Slouqi 3,210 Aain Hizzine Taibet Bourday Chmistar 361 Baalbek 160 2,284 515 Aain Es-Siyaa Chadoura Kfar Talia Bednayel 1,235 Dabach Haouch Baalbak Brital Nabi 159 En-Nabi 2,328 Temnine Beit Haouch 4,552 Chbay 318 El-Faouqa Chama Snaid Haour Chaaibe 1,223 605 Mousraye 83 Taala 16 9 Khodr 192 Qaa -

Request for an Inspection on the Impacts of the Bisri Dam Project in Lebanon

June 24th, 2019 To: Executive Secretary, the Inspection Panel 1818 H Street NW, MSN 10 - 1007, Washington, DC 20433, USA REQUEST FOR AN INSPECTION ON THE IMPACTS OF THE BISRI DAM PROJECT IN LEBANON We, the Lebanon Eco Movement (LEM), are a network of 60 environmental NGOs advocating for sustainable development and the protection of the environment in Lebanon. The movement co- founded the Save the Bisri Valley Campaign in collaboration with the affected communities and a group of experts. LEM is also a member in the Arab Watch Coalition. In this request, we represent a group of residents and landowners whose addresses and signatures are enclosed below. We are also attaching a copy of a new petition that gathered more than 30,000 signatures (Annex Z.b). Our network submitted an earlier request for inspection on June 6th, 2018, and the Panel did not recommend investigation. While we acknowledge the Panel’s previous efforts to address our concerns, we believe that the first complaint was not satisfactorily answered. The Recommendation Report given by the Panel focused more on ensuring a checklist of studies is filled rather than evaluating the validity of the studies and, most importantly, the grave social, environmental and economic harms the project poses to Lebanon. Consequently, the Panel accepted inaccurate information and factual discrepancies provided by the Bank Management. Additionally, given the emergence of new evidence and circumstances, we are submitting a new request for inspection. Our concerns have been already conveyed to the relevant authorities and to the World Bank Management in Beirut. However, the concerns were either disregarded, or addressed with neglect and delay. -

Baalbek Hermel Zahleh Jbayl Aakar Koura Metn Batroun West Bekaa Zgharta Kesrouane Rachaiya Miniyeh-Danniyeh Bcharreh Baabda Aale

305 307308 Borhaniya - Rehwaniyeh Borj el Aarab HakourMazraatKarm el Aasfourel Ghatas Sbagha Shaqdouf Aakkar 309 El Aayoun Fadeliyeh Hamediyeh Zouq el Hosniye Jebrayel old Tekrit New Tekrit 332ZouqDeir El DalloumMqachrine Ilat Ain Yaaqoub Aakkar El Aatqa Er Rouaime Moh El Aabdé Dahr Aayas El Qantara Tikrit Beit Daoud El Aabde 326 Zouq el Hbalsa Ein Elsafa - Akum Mseitbeh 302 306310 Zouk Haddara Bezbina Wadi Hanna Saqraja - Ein Eltannur 303 Mar Touma Bqerzla Boustane Aartoussi 317 347 Western Zeita Al-Qusayr Nahr El Bared El318 Mahammara Rahbe Sawadiya Kalidiyeh Bhannine 316 El Khirbe El Houaich Memnaa 336 Bebnine Ouadi Ej jamous Majdala Tashea Qloud ElEl Baqie Mbar kiye Mrah Ech Chaab A a k a r Hmaire Haouchariye 34°30'0"N 338 Qanafez 337 Hariqa Abu Juri BEKKA INFORMALEr Rihaniye TENTEDBaddouaa El Hmaira SETTLEMENTS Bajaa Saissouq Jouar El Hachich En Nabi Kzaiber Mrah esh Shmis Mazraat Et Talle Qarqaf Berkayel Masriyeh Hamam El Minié Er Raouda Chane Mrah El Dalil Qasr El Minie El Kroum El Qraiyat Beit es Semmaqa Mrah Ez Zakbe Diyabiyeh Dinbou El Qorne Fnaydek Mrah el Arab Al Quasir 341 Beit el Haouch Berqayel Khraibe Fnaideq Fissane 339 Beit Ayoub El Minieh - Plot 256 Bzal Mishmish Hosh Morshed Samaan 340 Aayoun El Ghezlane Mrah El Ain Salhat El Ma 343 Beit Younes En Nabi Khaled Shayahat Ech Cheikh Maarouf Habchit Kouakh El Minieh - Plots: 1797 1796 1798 1799 Jdeidet El Qaitaa Khirbit Ej Jord En Nabi Youchaa Souaisse 342 Sfainet el Qaitaa Jawz Karm El Akhras Haouch Es Saiyad AaliHosh Elsayed Ali Deir Aamar Hrar Aalaiqa Mrah Qamar ed Dine -

Usaid/Lebanon Lebanon Industry Value Chain Development (Livcd) Project

USAID/LEBANON LEBANON INDUSTRY VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT (LIVCD) PROJECT LIVCD QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT - YEAR 6, QUARTER 3 APRIL 1 – JUNE 30, 2018 JULY 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. Contents ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................. 3 PROJECT OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................. 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.......................................................................................................... 6 KEY HIGHLIGHTS ................................................................................................................... 8 PERFORMANCE INDICATOR RESULTS FOR Q3 FY18 AND LIFE OF PROJECT ........... 11 IMPROVE VALUE CHAIN COMPETITIVENESS ................................................................. 15 PROCESSED FOODS VALUE CHAIN .................................................................................. 15 RURAL TOURISM VALUE CHAIN........................................................................................ 23 OLIVE OIL VALUE CHAIN .......................................................................................................... 31 POME FRUIT VALUE CHAIN (APPLES AND PEARS) ....................................................... 40 CHERRY VALUE CHAIN ...................................................................................................... -

Ground Water in the Astern Mediterranean and Western Asia

VST/ESA/112 Department of Technical Co-operation for Development Natural Resources / Water Series No. 9 GROUND WATER IN THE ASTERN MEDITERRANEAN AND WESTERN ASIA zrx 7 X -A !;•;* sJLo a/o. £ f?~ X^ II ' 4 'I HH vm UNITED NATIONS New York, 1982 LEBANON Area: 10,400 km2 Population: 2,961,000 (United Nations estimate, 1976) General Lebanon is a mountainous country dominated by two parallel north-south mountain ranges: the coastal Lebanon range and the inland Anti-Lebanon range. The narrow coastal strip which borders the Mediterranean broadens in places producing the Akkar plain in the north and smaller alluvial areas in the Tripoli and Beirut localities. The inland elevated central Bekaa plain, lying between 650 and 1,000 m, is the source of the country's two major rivers, the Orontes and the Litani. Elevations up to 3,000 m along the Lebanon range and 2,300 m along the Anti-Lebanon range have a pronounced effect on the country's climate. Lebanon's topographical configuration, with its orographical and geological structure, divides the country, into two major areas: (a) The Mediterranean watershed (5,500 km2) where numerous short costal rivers descend directly from spring sources on the western slopes of the Lebanon into the sea; '(b) An interior watershed (4,700 km2), where the Orontes and Litani rivers eventually discharge into the sea. The climate varies markedly across the country, owing to its unique physiography. The coastal mountain barrier intercepts both rain and humidity from the west; and the climate, vegetation and water resources graduate from a Mediterranean coastal environment to an inland Mesopotamian desert climate. -

Département De La Recherche Scientifique Présentation Des

Département de la Recherche Scientifique Edition: 02 Date : Mai 2021 Présentation des Laboratoires de Recherche Date de la mise à jour: Faculté de Santé Page 1 of 40 Pubique Laboratoire Microbiologie Santé et Environnement The “Laboratoire Microbiologie Santé et Environnement (LMSE)” - Health and Environment Microbiology Laboratory - is a research laboratory affiliated to the Doctoral School of Science and technology and the Faculty of Public Health at the Lebanese University, the only public institution for higher education in Lebanon. LMSE was created in 2011 under the leadership of Prof. Monzer Hamze and is currently staffed by a group of experts in the field of medical and food microbiology including 3 professors, 7 assistant professors, 2 MD and hospital practitioner, 6 technicians, 1 administrative employer and 5 current PhD students. LMSE research activities cover a wide variety of microbiology fields, including COVID-19, tuberculosis, antimicrobial resistance resistance, probiotics and antimicrobial peptides, immunity and infections, parasitic diseases, molecular typing, applied bioinformatics, and natural bioactive substances. LMSE is now a well-recognized laboratory in the field of surveillance of infectious diseases in Lebanon. Its activities strengthen the understanding of the complexity of microbial diseases and the monitoring of their national dynamics to provide epidemiological data used for national prevention and care plan. LMSE is accredited by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health to be the reference laboratory for COVID-19, tuberculosis and antimicrobial resistance in North Lebanon. It is also in active and fruitful collaboration with several Lebanese healthcare facilities to which it provides advanced diagnostic services. In cooperation with health authorities and national and international expertise, the LMSE also contributes to promote the quality of healthcare services by organizing specialized training workshops on diagnostics of infectious diseases. -

The Dissertation Committee for Georges Fadi Comair Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Georges Fadi Comair 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Georges Fadi Comair Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A New Approach for Water Planning, Management and Conflict Resolution in Lebanese Transboundary Basins: Hydrologic Modeling for Climate Variation and Water Policy Development Committee: Daene C. McKinney, Supervisor David R. Maidment Ben R. Hodges David J. Eaton Michael Scoullos A new approach for water planning, management and conflict resolutions in Lebanese transboundary basins: Hydrologic Modeling for Climate Variation and Water Policy Development by Georges Fadi Comair, B.S.C.E.; M.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2013 Dedication To my Grandfathers: General Georges Joseph Comair, M.D. and Robert Khoury-Helou, Ph.D. Je dédie cette thèse de doctorat à mes grands-pères: Dr. Général Georges Joseph Comair et Dr. Robert Khoury-Helou. Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere and endless gratitude to my supervisor and mentor Dr. Daene McKinney. During, my time at the University of Texas, Dr. McKinney provided me excellent guidance, and support, his expertise helped me better understand water planning and management in transboundary basins. Dr. McKinney allowed me to work on great projects and travel the world. My deep appreciation and gratitude to Dr. David Maidment, Dr. Ben Hodges, Dr. David Eaton and Dr. Michael Scoullos for being members of my dissertation committee. I thank them for their support first as teachers and also for their kind words of encouragement and valuable comments that helped me write this dissertation. -

Lebanon Roads and Employment Project Frequently Asked Questions

Lebanon Roads and Employment Project Frequently Asked Questions 1. What is the Roads and Employment Project (REP)? The Lebanon Roads and Employment Project (REP) is a US$200 million project that aims to improve transport connectivity along select paved road sections and create short-term jobs for the Lebanese and Syrians. The REP was approved by the World Bank (WB) Board of Executive Directors in February 2017 and ratified by the Lebanese Parliament in October 2018. The Project is co-financed by a US$45.4 million grant contribution from the Global Concessional Financing Facility (GCFF) which provides concessional financing to middle income countries hosting large numbers of refugees at rates usually reserved for the poorest countries. The project is implemented by the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) in coordination with the Ministry of Public Works and Transport (MPWT), noting that all the roads under the REP are under the jurisdiction of the MPWT. In response to the devastating impact of the economic and financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic on the agriculture sector and food security, the project was restructured in March 2021: a third objective was added and a US$10 million reallocation approved to provide direct support to farmers engaged in crop and livestock production (Please refer to questions # 18 to 26) 2. What are the Components of the Roads and Employment Project? The REP originally had three components. Following its restructuring in March 2021, a fourth component was added to address the impact of the -

Usaid/Lebanon Lebanon Industry Value Chain Development (Livcd) Project

USAID/LEBANON LEBANON INDUSTRY VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT (LIVCD) PROJECT LIVCD QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT JULY 1ST TO SEPTEMBER 30TH, 2013 – Q4 2013 Program Title: USAID/ LEBANON INDUSTRY VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT (LIVCD) PROJECT Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Lebanon- Office of Economic Growth Contract Number: AID-268-C-12-00001 Contractor: DAI Date of Publication: July 2013 Author: DAI OCTOBER 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................... III INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 1.1 PROGRAM OVERVIEW AND OBJECTIVES ............................................................... 4 1.2 OVERVIEW OF QUARTERLY REPORT ............................................................................ 4 1.0 WORK PLAN INITIAL IMPLEMENTATION .............................................................. 6 2.1 VALUE CHAIN SELECTION AND WORK PLAN PREPARATION ........................................ 6 2.2 IMPLEMENTATION OF PRIORITY ACTIVITIES IN EACH VALUE CHAIN ............................. 7 2.2.1 CROSS-CUTTING VALUE CHAIN ACTIVITIES ............................................................. 7 2.2.2 FLORICULTURE ....................................................................................................... 9 2.2.3 GRAPES .................................................................................................................. -

LEBANON Resettlement Action COUNCIL for DEVELOPMENT and DOCUMENT TYPE: Plan RECONSTRUCTION

RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN FOR THE AWALI-BEIRUT WATER CONVEYOR PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: EARTH LINK AND ADVANCED RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT S.A.R.L. (ELARD) Public Disclosure Authorized Submitted to: COUNCIL FOR DEVELOPMENT AND RECONSTRUCTION (CDR) Date of Submission: Public Disclosure Authorized August 4th, 2010 RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN COUNCIL FOR DEVELOPMENT AND RECONSTRUCTION (CDR) ESIA FOR AWALI-BEIRUT WATER CONVEYER PROJECT PROJECT INFORMATION ELARD LEBANON Resettlement Action COUNCIL FOR DEVELOPMENT AND DOCUMENT TYPE: Plan RECONSTRUCTION PROJECT REF:: ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT NO. OF PAGES: 87 ESIA for Awali-Beirut Water Conveyer Project VERSION FINAL REPORT APPROVED BY Ramez Kayal General Manager REVIEWED BY Ricardo Khoury Senior Environmental Specialist Rachad Ghanem Senior Hydrogeologist/ Project Manager Hanadi Musharafiyeh Social Economist Wafaa Halabi Socio-Economist PREPARED BY Basma Shames Geologist / Field Coordinator Carlo Bekhazi Environmental Consultant Ghada Chehab Senior Environmental Consultant Rana Ghattas Quality Management Responsible DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by ELARD , with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. The information contained in this report is, to the best of our knowledge, correct at the time of printing. The interpretations and recommendations are based on our experience, using reasonable professional skill and judgment, and based upon the information that was available to us. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility whatsoever to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known.