Glacial Landforms and Quaternary Landscape Development in Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ice on the Rocks: a Glacier Shapes the Land

Title Advance Preparation Ice on the Rocks: A Glacier Shapes the 1. Place rocks and sand in each bowl and add Land 2.5 cm of water. Allow the sand to settle, and freeze the contents solid. Later, add water until Investigative Question the bowls are nearly full and again freeze What are glaciers and how did they change the solid. These are the "glaciers" for part 1. landscape of Illinois? 2. Assemble the other materials. You may wish to do parts 1 and 3 in a laboratory setting Overview or out-of-doors because these activities are Students learn how glaciers, through abrasion, likely to be messy. transportation, and deposition, change the 3. Copy the student pages. surfaces over which they flow. Introducing the Activity Objective Hold up a square, normal-sized ice cube. Next Students conduct simulations and demonstrate to it hold up a toothpick that is as tall as the what a glacier does and how it can change the cube is thick. Ask students to picture the tallest landscape. building in Chicago, the Sears Tower. If the toothpick represents the Sears Tower, the ice Materials cube represents a glacier. The Sears Tower is Introductory activity: an ice cube and a about as tall as a glacier was thick! That was toothpick. the Wisconsinan glacier that was over 400 Part 1. For each group of five students: two meters thick and covered what is now the city plastic 1- or 2-qt. bowls; several small, of Chicago! irregularly shaped rocks or pebbles; a handful of coarse sand; a common, unglazed brick or a Procedure masonry brick (washed and cleaned); several Part 1 flat paving stones (limestone); water; access to 1. -

A Post-Caledonian Dolerite Dyke from Magerøy, North Norway: Age and Geochemistry

A post-Caledonian dolerite dyke from Magerøy, North Norway: age and geochemistry DAVID ROBERTS, JOHN G. MITCHELL & TORGEIR B. ANDERSEN Roberts. D., Mitchell, J. G. & Andersen, T. B.: A post-Caledonian dolerite dyke from Magerøy, North Norway: age and geochemistry. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 71, pp. 28�294. Oslo 1991 . ISSN 0029-196X. A post-Caledonian, NW-SE trending, dolerite dyke on Magerøy has a geochemicalsignature comparable to that of continental tholeiites. Clinopyroxenes from three samples of the dolerite gave K-Ar ages of ca. 312, ca. 302 and ca. 266 Ma, suggesting a Perrno-Carboniferous age. In view of low K20 contents of the pyroxenes and the possible presence of excess argon, it is argued that the most reliable estimate of the emplacement age of the dyke is provided by the unweighted mean value, namely 293 ± 22 Ma. This Late Carboniferous age coincides with the later stages of a major phase of rifting and crustal extension in adjacent offshore areas. The dyke is emplaced along a NW-SE trending fault. Parallel or subparallel faults on Magerøy and in other parts of northem Finnmark may thus carry a component of Carboniferous crustal extension in their polyphase movement histories. David Roberts, Geological Survey of Norway, Post Box 3006-Lade, N-7(}()2 Trondheim, Norway; John G. Mitchell, Department of Physics, The University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, England; Torgeir B. Andersen, Institutt for geologi, Post Box 1047, University of Oslo, N-41316 Oslo 3, Norway. In the Caledonides of northernmost Norway, maficdy kes tolites indicate an Early Silurian (Llandovery) age (Hen are common in many parts of the metamorphic allochthon ningsmoen 1961; Føyn 1967; Bassett 1985) for part of the and are invariably deformed and metamorphosed, locally succession. -

Ribbed Bedforms in Palaeo-Ice Streams Reveal Shear Margin

https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2020-336 Preprint. Discussion started: 21 November 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Ribbed bedforms in palaeo-ice streams reveal shear margin positions, lobe shutdown and the interaction of meltwater drainage and ice velocity patterns Jean Vérité1, Édouard Ravier1, Olivier Bourgeois2, Stéphane Pochat2, Thomas Lelandais1, Régis 5 Mourgues1, Christopher D. Clark3, Paul Bessin1, David Peigné1, Nigel Atkinson4 1 Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique, UMR 6112, CNRS, Le Mans Université, Avenue Olivier Messiaen, 72085 Le Mans CEDEX 9, France 2 Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique, UMR 6112, CNRS, Université de Nantes, 2 rue de la Houssinière, BP 92208, 44322 Nantes CEDEX 3, France 10 3 Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK 4 Alberta Geological Survey, 4th Floor Twin Atria Building, 4999-98 Ave. Edmonton, AB, T6B 2X3, Canada Correspondence to: Jean Vérité ([email protected]) Abstract. Conceptual ice stream landsystems derived from geomorphological and sedimentological observations provide 15 constraints on ice-meltwater-till-bedrock interactions on palaeo-ice stream beds. Within these landsystems, the spatial distribution and formation processes of ribbed bedforms remain unclear. We explore the conditions under which these bedforms develop and their spatial organisation with (i) an experimental model that reproduces the dynamics of ice streams and subglacial landsystems and (ii) an analysis of the distribution of ribbed bedforms on selected examples of paleo-ice stream beds of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. We find that a specific kind of ribbed bedforms can develop subglacially 20 from a flat bed beneath shear margins (i.e., lateral ribbed bedforms) and lobes (i.e., submarginal ribbed bedforms) of ice streams. -

WELLESLEY TRAILS Self-Guided Walk

WELLESLEY TRAILS Self-Guided Walk The Wellesley Trails Committee’s guided walks scheduled for spring 2021 are canceled due to Covid-19 restrictions. But… we encourage you to take a self-guided walk in the woods without us! (Masked and socially distanced from others outside your group, of course) Geologic Features Look for geological features noted in many of our Self-Guided Trail Walks. Featured here is a large rock polished by the glacier at Devil’s Slide, an esker in the Town Forest (pictured), and a kettle hole and glacial erratic at Kelly Memorial Park. Devil’s Slide 0.15 miles, 15 minutes Location and Parking Park along the road at the Devil’s Slide trailhead across the road from 9 Greenwood Road. Directions From the Hills Post Office on Washington Street, turn onto Cliff Road and follow for 0.4 mile. Turn left onto Cushing Road and follow as it winds around for 0.15 mile. Turn left onto Greenwood Road, and immediately on your left is the trailhead in patch of woods. Walk Description Follow the path for about 100 yards to a large rock called the Devil’s Slide. Take the path to the left and climb around the back of the rock to get to the top of the slide. Children like to try out the slide, which is well worn with use, but only if it is dry and not wet or icy! Devil’s Slide is one of the oldest rocks in Wellesley, more than 600,000,000 years old and is a diorite intrusion into granite rock. -

Hele Troms Og Finnmark Hele Tromsø

Fylkestingskandidater Kommunestyrekandidater 1 2 3 1 2 3 Ivar B. Prestbakmo Anne Toril E. Balto Irene Lange Nordahl Marlene Bråthen Mats Hegg Jacobsen Olaug Hanssen Salangen Karasjok Sørreisa 4 5 6 4 5 6 Fred Johnsen Rikke Håkstad Kurt Wikan Edmund Leiksett Rita H. Roaldsen Magnus Eliassen Tana Bardu Sør-Varanger 7. Kine Svendsen 16. Hans-Ole Nordahl 25. Tore Melby Hele Hele 8. Glenn Maan 17. May Britt Pedersen 26. Kjell Borch 7. Marlene Bråthen, 10. Hugo Salamonsen, 13. Kurt Michalsen, 9. Wenche Skallerud 18. Frode Pettersen 27. Ole Marius Johnsen Tromsø Nordkapp Skjervøy 10. Bernt Bråthen 19. Mona Wilhelmsen 28. Sigurd Larsen 8. Jan Martin Rishaug, 11. Linn-Charlotte 14. Grethe Liv Olaussen, Troms og Finnmark Tromsø 11. Klaus Hansen 20. Fredrik Hanssen 29. Per-Kyrre Larsen Alta Nordahl, Sørreisa Porsanger 12. Ida Johnsen 21. Dag Nordvang 30. Peter Ørebech 9. Karin Eriksen, 12. Klemet Klemetsen, 15. Gunnleif Alfredsen, 13. Kathrine Strandli 22. Morten Furunes 31. Sandra Borch Kvæfjord Kautokeino Senja senterpartiet.no/troms senterpartiet.no/tromso 14. John Ottosen 23. Asgeir Slåttnes 15. Judith Maan 24. Kåre Skallerud VÅR POLITIKK VÅR POLITIKK Fullstendig program finner du på Fullstendig program finner du på For hele Tromsø senterpartiet.no/tromso for hele Troms og Finnmark senterpartiet.no/troms anlegg og andre stukturer tilpas- Senterpartiet vil ha tjenester Det skal være trygt å bli Næringsutvikling – det er i • Øke antallet lærlingeplasser. nord, for å styrke vår identitet og set aktivitet og friluftsliv Mulighetenes landsdel Helse og beredskap nær folk og ta hele Tromsø i gammel i Tromsø nord verdiene skapes Senterpartiet vil: Senterpartiet vil: • Utvide borteboerstipendet, øke stolthet. -

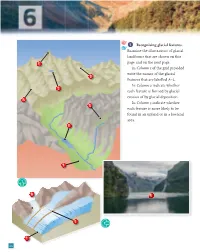

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Pulse-To-Pulse Coherent Doppler Measurements of Waves and Turbulence

1580 JOURNAL OF ATMOSPHERIC AND OCEANIC TECHNOLOGY VOLUME 16 Pulse-to-Pulse Coherent Doppler Measurements of Waves and Turbulence FABRICE VERON AND W. K ENDALL MELVILLE Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California (Manuscript received 7 August 1997, in ®nal form 12 September 1998) ABSTRACT This paper presents laboratory and ®eld testing of a pulse-to-pulse coherent acoustic Doppler pro®ler for the measurement of turbulence in the ocean. In the laboratory, velocities and wavenumber spectra collected from Doppler and digital particle image velocimeter measurements compare very well. Turbulent velocities are obtained by identifying and ®ltering out deep water gravity waves in Fourier space and inverting the result. Spectra of the velocity pro®les then reveal the presence of an inertial subrange in the turbulence generated by unsteady breaking waves. In the ®eld, comparison of the pro®ler velocity records with a single-point current measurement is satisfactory. Again wavenumber spectra are directly measured and exhibit an approximate 25/3 slope. It is concluded that the instrument is capable of directly resolving the wavenumber spectral levels in the inertial subrange under breaking waves, and therefore is capable of measuring dissipation and other turbulence parameters in the upper mixed layer or surface-wave zone. 1. Introduction ence on the measurement technique. For example, pro- ®ling instruments have been very successful in mea- The surface-wave zone or upper surface mixed layer suring microstructure at greater depth (Oakey and Elliot of the ocean has received considerable attention in re- 1982; Gregg et al. 1993), but unless the turnaround time cent years. -

Large-Scale Rock Slope Failures in the Eastern Pyrenees: Identifying a Sparse but Significant Population in Paraglacial and Parafluvial Contexts

Large-scale rock slope failures in the eastern Pyrenees: identifying a sparse but significant population in paraglacial and parafluvial contexts David Jarman1, Marc Calvet2, Jordi Corominas3, Magali Delmas2, Yanni Gunnell4 1 Mountain Landform Research, Scotland 2 University of Perpignan, CNRS UMR 7194, France 3 Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain 4 University of Lyon, CNRS UMR 5600, France ABSTRACT This first overview of large-scale rock slope failure (RSF) in the Pyrenees addresses the eastern third of the range. Around 30 principal RSFs >0.25 km2 and 20 lesser or uncertain cases have been identified from remote imagery and groundtruthing. Compared with other European mountain ranges, RSF incidence is relatively sparse, displays no obvious regional trend or spatial clustering, and occurs across diverse landscape types, if mainly on metamorphic rocks. A transition is observed from paraglacial RSFs in formerly-glaciated valleys to what are here termed ‘parafluvial’ RSFs, within wholly or mainly fluvial valleys but where slope failure is not directly provoked by or linked to river erosion. RSFs are particularly found in three topographic settings: (i) at cirque and trough-head thresholds (transition zones of elevated instability between cirque and main glaciated trough walls); (ii) near the upper or outer periphery of the ice field, where glacial adaptation of fluvial valleys is incomplete; and (iii) in fluvial valleys beyond glacial limits where incision is locally intense. RSF is absent from the range divide, from within cirques, and from most main valleys. In the montane areas, RSF is strongly associated with vestiges of preglacial summit surfaces, confirming that plateau ridges are less stable than sharpened crests and horns. -

WEST NORWEGIAN FJORDS UNESCO World Heritage

GEOLOGICAL GUIDES 3 - 2014 RESEARCH WEST NORWEGIAN FJORDS UNESCO World Heritage. Guide to geological excursion from Nærøyfjord to Geirangerfjord By: Inge Aarseth, Atle Nesje and Ola Fredin 2 ‐ West Norwegian Fjords GEOLOGIAL SOCIETY OF NORWAY—GEOLOGICAL GUIDE S 2014‐3 © Geological Society of Norway (NGF) , 2014 ISBN: 978‐82‐92‐39491‐5 NGF Geological guides Editorial committee: Tom Heldal, NGU Ole Lutro, NGU Hans Arne Nakrem, NHM Atle Nesje, UiB Editor: Ann Mari Husås, NGF Front cover illustrations: Atle Nesje View of the outer part of the Nærøyfjord from Bakkanosi mountain (1398m asl.) just above the village Bakka. The picture shows the contrast between the preglacial mountain plateau and the deep intersected fjord. Levels geological guides: The geological guides from NGF, is divided in three leves. Level 1—Schools and the public Level 2—Students Level 3—Research and professional geologists This is a level 3 guide. Published by: Norsk Geologisk Forening c/o Norges Geologiske Undersøkelse N‐7491 Trondheim, Norway E‐mail: [email protected] www.geologi.no GEOLOGICALSOCIETY OF NORWAY —GEOLOGICAL GUIDES 2014‐3 West Norwegian Fjords‐ 3 WEST NORWEGIAN FJORDS: UNESCO World Heritage GUIDE TO GEOLOGICAL EXCURSION FROM NÆRØYFJORD TO GEIRANGERFJORD By Inge Aarseth, University of Bergen Atle Nesje, University of Bergen and Bjerkenes Research Centre, Bergen Ola Fredin, Geological Survey of Norway, Trondheim Abstract Acknowledgements Brian Robins has corrected parts of the text and Eva In addition to magnificent scenery, fjords may display a Bjørseth has assisted in making the final version of the wide variety of geological subjects such as bedrock geol‐ figures . We also thank several colleagues for inputs from ogy, geomorphology, glacial geology, glaciology and sedi‐ their special fields: Haakon Fossen, Jan Mangerud, Eiliv mentology. -

Jens Esmark's Mountain Glacier Traverse 1823 À the Key to His

bs_bs_banner Jens Esmark’s mountain glacier traverse 1823 À the key to his discovery of Ice Ages GEIR HESTMARK Hestmark, G. 2018 (January): Jens Esmark’s mountain glacier traverse 1823 À the key to his discovery of Ice Ages. Boreas, Vol. 47, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/bor.12260. ISSN 0300-9483. The discovery of Ice Ages is one of the most revolutionary advances made in the Earth sciences. In 1824 Danish- Norwegian geoscientist Jens Esmark published a paper stating that there was indisputable evidence that Norway and other parts of Europe had previously been covered by enormous glaciers carving out valleys and fjords, in a cold climate caused by changes in the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit. Esmark and his travel companion Otto Tank arrived at this insight byanalogous reasoning: enigmatic landscape features theyobserved close to sea level alongtheNorwegian coast strongly resembled features they observed in the front of a retreating glacier during a mountain traverse in the summer of 1823. Which glacier they observed up close has however remained a mystery, and thus an essential piece of information in the story of this discovery has been missing. Based on previously unknown archive sources, supplemented by field study, I here identify the key locality as the glacier Rauddalsbreen. This is the northernmost outlet glacier from Jostedalsbreen, the largest glacier in mainland Europe. Here the foreland exposed byglacier retreat since the Little Ice Age maximum around AD 1750 contains a rich collection of glacial deposits and erosional forms. The point of enlightenment is more precisely identified to be a specific moraine and its distal sandur at 61°53026″N, 7°26043″E. -

Jens Esmark – Meteorologist

1 2 Jens Esmark’s Christiania (Oslo) meteorological observations 3 1816-1838: The first long term continuous temperature record 4 from the Norwegian capital homogenized and analysed 5 6 7 Geir Hestmark1 and Øyvind Nordli2 8 9 1 Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis, CEES, Department of 10 Biosciences, Box 1066 Blindern, University of Oslo, N-0316 Oslo, Norway 11 2 Norwegian Meteorological Institute (MET Norway), 12 Research and Development Department, Division for Model and Climate Analysis, 13 P.O. Box 43 Blindern, N-0313 Oslo, Norway 14 15 Correspondence to: Geir Hestmark ([email protected]) 16 17 Abstract 18 In 2010 we rediscovered the complete set of meteorological observation protocols 19 made by professor Jens Esmark (1762-1839) during his years of residence in the 20 Norwegian capital of Oslo (then Christiania). From 1 January 1816 to 25 January 21 1839 Esmark at his house in Øvre Voldgate in the morning, early afternoon and 22 late evening recorded air temperature with state of the art thermometers. He also 23 noted air pressure, cloud cover, precipitation and wind directions, and 24 experimented with rain gauges and hygrometers. From 1818 to the end of 1838 he 25 twice a month provided weather tables to the official newspaper Den norske 26 Rigstidende, and thus acquired a semi-official status as the first Norwegian state 27 meteorologist. This paper evaluates the quality of Esmark’s temperature 28 observations, presents new metadata, new homogenization and analysis of monthly 29 means. Three significant shifts in the measurement series were detected, and 30 suitable corrections are proposed. -

An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250

The Ohio Naturalist, PUBLISHED BY The Biological Club of the Ohio State University. Volume VIII. JANUARY. 1908. No. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS. SCHEPFEL—An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250 AN ESKER GROUP SOUTH OF DAYTON, OHIO.1 EARL R. SCHEFFEL Contents. Introduction. General Discussion of Eskers. Preliminary Description of Region. Bearing on Archaeology. Topographic Relations. Theories of Origin. Detailed Description of Eskers. Kame Area to the West of Eskers. Studies. Proximity of Eskers. Altitude of These Deposits. Height of Eskers. Composition of Eskers. Reticulation. Rock Weathering. Knolls. Crest-Lines. Economic Importance. Area to the East. Conclusion and Summary. Introduction. This paper has for its object the discussion of an esker group2 south of Dayton, Ohio;3 which group constitutes a part of the first or outer moraine of the Miami Lobe of the Late Wisconsin ice where it forms the east bluff of the Great Miami River south of Dayton.4 1. Given before the Ohio Academy of Science, Nov. 30, 1907, at Oxford, O., repre- senting work performed under the direction of Professor Frank Carney as partial requirement for the Master's Degree. 2. F: G. Clapp, Jour, of Geol., Vol. XII, (1904), pp. 203-210. 3. The writer's attention was first called to the group the past year under the name "Morainic Ridges," by Professor W. B. Werthner, of Steele High School, located in the city mentioned. Professor Werthner stated that Professor August P. Foerste of the same school and himself had spent some time together in the study of this region, but that the field was still clear for inves- tigation and publication.