Arxiv:0908.0646V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:2012.09981V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 17 Dec 2020 2 O](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3257/arxiv-2012-09981v1-astro-ph-sr-17-dec-2020-2-o-73257.webp)

Arxiv:2012.09981V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 17 Dec 2020 2 O

Contrib. Astron. Obs. Skalnat´ePleso XX, 1 { 20, (2020) DOI: to be assigned later Flare stars in nearby Galactic open clusters based on TESS data Olga Maryeva1;2, Kamil Bicz3, Caiyun Xia4, Martina Baratella5, Patrik Cechvalaˇ 6 and Krisztian Vida7 1 Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences 251 65 Ondˇrejov,The Czech Republic(E-mail: [email protected]) 2 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Universitetsky pr. 13, 119234, Moscow, Russia 3 Astronomical Institute, University of Wroc law, Kopernika 11, 51-622 Wroc law, Poland 4 Department of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kotl´aˇrsk´a2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic 5 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia Galileo Galilei, Vicolo Osservatorio 3, 35122, Padova, Italy, (E-mail: [email protected]) 6 Department of Astronomy, Physics of the Earth and Meteorology, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Informatics, Comenius University in Bratislava, Mlynsk´adolina F-2, 842 48 Bratislava, Slovakia 7 Konkoly Observatory, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, H-1121 Budapest, Konkoly Thege Mikl´os´ut15-17, Hungary Received: September ??, 2020; Accepted: ????????? ??, 2020 Abstract. The study is devoted to search for flare stars among confirmed members of Galactic open clusters using high-cadence photometry from TESS mission. We analyzed 957 high-cadence light curves of members from 136 open clusters. As a result, 56 flare stars were found, among them 8 hot B-A type ob- jects. Of all flares, 63 % were detected in sample of cool stars (Teff < 5000 K), and 29 % { in stars of spectral type G, while 23 % in K-type stars and ap- proximately 34% of all detected flares are in M-type stars. -

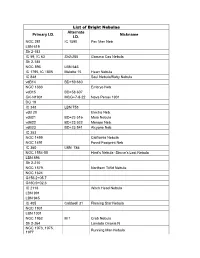

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

198 7Apjs. . .63. .645U the Astrophysical Journal Supplement

.645U The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 63:645-660,1987 March © 1987. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. .63. 7ApJS. A CO SURVEY OF THE DARK NEBULAE IN PERSEUS, TAURUS, AND AURIGA 198 H. Ungerechts and P. Thaddeus Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Columbia University Received 1986 February 20; accepted 1986 September 4 ABSTRACT A region of 750 square degrees including the well-known dark nebulae in Perseus, Taurus, and Auriga was surveyed in the 115 GHz, J = l-0 line of CO at an angular resolution of 0?5. The spectral resolution of the survey is 250 kHz, or 0.65 km s-1, and the rms noise per spectrometer channel is 0.14 K. Emission was detected from nearly 50% of the observed positions; most positions with emission are in the Taurus-Auriga dark nebulae, a cloud associated with IC 348 and NGC 1333, and a cloud associated with the California nebula (NGC 1499) and NGC 1579, which overlaps the northern Taurus-Auriga nebulae but is separated from them in velocity. Other objects seen in this survey are several small clouds at Galactic latitude —25° to —35° southwest of the Taurus clouds, and the L1558 and L1551 clouds in the south. The mass of each of the IC 348 and NGC 1499 4 4 clouds is about 5X10 M0, and that of the Taurus-Auriga clouds about 3.5 X10 M0; the total mass of all 5 clouds surveyed is about 2x10 Af0. On a large scale, the rather quiescent Taurus clouds are close to virial equilibrium, but the IC 348 and NGC 1499 clouds are more dynamically active. -

National Radio Astronomy Observatory 1977 National Radio Astronomy Observatory

NATIONAL RADIO ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY 1977 NATIONAL RADIO ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY 1977 OBSERVING SUMMARY Some Highlights of the 1976 Research Program The first two VIA antennas were used successfully as an interferometer in February, 1976. By the end of 1976, six antennas had been operated as an interferometer in test observing runs. Amongst the improvements to existing facilities are the new radiometers at 9 cm and at 25/6 cm for Green Bank. The pointing accuracy of the 140-foot antenna was improved by insulating critical parts of the structure. The 300-foot telescope was used to detect the redshifted hydrogen absorption feature in the spectrum of the radio source AO 0235+164. This is the first instance in which optical and radio spectral lines have been measured in a source having large redshift. The 140-foot telescope was used as an element of a Very Long Baseline Interferometer in the de¬ tection of an extremely small radio source in the Galactic Center. This source, with dimensions less than the solar system, is similar to, but less luminous than, compact sources observed in other galaxies. The interferometer was used to detect emission from the binary HR1099. Subsequently, a large radio flare was observed simultaneously with a Ly-a and H-cc outburst from the star. New molecules detected with the 36-foot telescope include a number of deuterated species such as DC0+, and ketene, the least saturated version of the CCO molecule frame. OBSERVING HOURS <CO 1 1967 ' 1968 ' ' 1969 ' 1970 ' 1971 ' 1972 ' 1973 ' 1974 ' 1975 ' 1976 ' 1977 ' 1978 ' 1979 ' 1980 ' 1981 ' 1982 ' 1983 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 FISCAL YEAR CALENDAR YEAR Fig, 1. -

A Compendium of Distances to Molecular Clouds in the Star Formation Handbook?,?? Catherine Zucker1, Joshua S

A&A 633, A51 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936145 & c ESO 2020 Astrophysics A compendium of distances to molecular clouds in the Star Formation Handbook?,?? Catherine Zucker1, Joshua S. Speagle1, Edward F. Schlafly2, Gregory M. Green3, Douglas P. Finkbeiner1, Alyssa Goodman1,5, and João Alves4,5 1 Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, One Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 3 Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, Physics and Astrophysics Building, 452 Lomita Mall, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 4 University of Vienna, Department of Astrophysics, Türkenschanzstraße 17, 1180 Vienna, Austria 5 Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, 10 Garden St, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Received 21 June 2019 / Accepted 12 August 2019 ABSTRACT Accurate distances to local molecular clouds are critical for understanding the star and planet formation process, yet distance mea- surements are often obtained inhomogeneously on a cloud-by-cloud basis. We have recently developed a method that combines stellar photometric data with Gaia DR2 parallax measurements in a Bayesian framework to infer the distances of nearby dust clouds to a typical accuracy of ∼5%. After refining the technique to target lower latitudes and incorporating deep optical data from DECam in the southern Galactic plane, we have derived a catalog of distances to molecular clouds in Reipurth (2008, Star Formation Handbook, Vols. I and II) which contains a large fraction of the molecular material in the solar neighborhood. Comparison with distances derived from maser parallax measurements towards the same clouds shows our method produces consistent distances with .10% scatter for clouds across our entire distance spectrum (150 pc−2.5 kpc). -

NGC-1579 Diffuse Nebula in Perseus (The Northern Trifid) Introduction the Purpose of the Observer’S Challenge Is to Encourage the Pursuit of Visual Observing

MONTHLY OBSERVER’S CHALLENGE Las Vegas Astronomical Society Compiled by: Roger Ivester, Boiling Springs, North Carolina & Fred Rayworth, Las Vegas, Nevada With special assistance from: Rob Lambert, Las Vegas, Nevada January 2013 NGC-1579 Diffuse Nebula in Perseus (The Northern Trifid) Introduction The purpose of the observer’s challenge is to encourage the pursuit of visual observing. It is open to everyone that is interested, and if you are able to contribute notes, drawings, or photographs, we will be happy to include them in our monthly summary. Observing is not only a pleasure, but an art. With the main focus of amateur astronomy on astrophotography, many times people tend to forget how it was in the days before cameras, clock drives, and GOTO. Astronomy depended on what was seen through the eyepiece. Not only did it satisfy an innate curiosity, but it allowed the first astronomers to discover the beauty and the wonderment of the night sky. Before photography, all observations depended on what the astronomer saw in the eyepiece, and how they recorded their observations. This was done through notes and drawings and that is the tradition we are stressing in the observers challenge. By combining our visual observations with our drawings, and sometimes, astrophotography (from those with the equipment and talent to do so), we get a unique understanding of what it is like to look through an eyepiece, and to see what is really there. The hope is that you will read through these notes and become inspired to take more time at the eyepiece studying each object, and looking for those subtle details that you might never have noticed before. -

December 2019 BRAS Newsletter

A Monthly Meeting December 11th at 7PM at HRPO (Monthly meetings are on 2nd Mondays, Highland Road Park Observatory). Annual Christmas Potluck, and election of officers. What's In This Issue? President’s Message Secretary's Summary Outreach Report Asteroid and Comet News Light Pollution Committee Report Globe at Night Member’s Corner – The Green Odyssey Messages from the HRPO Friday Night Lecture Series Science Academy Solar Viewing Stem Expansion Transit of Murcury Edge of Night Natural Sky Conference Observing Notes: Perseus – Rescuer Of Andromeda, or the Hero & Mythology Like this newsletter? See PAST ISSUES online back to 2009 Visit us on Facebook – Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Newsletter, Night Visions Page 2 of 25 December 2019 President’s Message I would like to thank everyone for having me as your president for the last two years . I hope you have enjoyed the past two year as much as I did. We had our first Members Only Observing Night (MOON) at HRPO on Sunday, 29 November,. New officers nominated for next year: Scott Cadwallader for President, Coy Wagoner for Vice- President, Thomas Halligan for Secretary, and Trey Anding for Treasurer. Of course, the nominations are still open. If you wish to be an officer or know of a fellow member who would make a good officer contact John Nagle, Merrill Hess, or Craig Brenden. We will hold our annual Baton Rouge “Gastronomical” Society Christmas holiday feast potluck and officer elections on Monday, December 9th at 7PM at HRPO. I look forward to seeing you all there. ALCon 2022 Bid Preparation and Planning Committee: We’ll meet again on December 14 at 3:00.pm at Coffee Call, 3132 College Dr F, Baton Rouge, LA 70808, UPCOMING BRAS MEETINGS: Light Pollution Committee - HRPO, Wednesday December 4th, 6:15 P.M. -

NOTES from OBSERVATORIES 353 from the Main Sequence, but Also

NOTES FROM OBSERVATORIES 353 from the main sequence, but also during the process of formation by gravitational contraction, which eventually carries the star to the main sequence. For a star as massive as ζ Persei probably is, however, the Helmholtz-Kelvin time scale rc is only of the 5 order of 10 years. While a rigorous calculation of tc for large masses has not been carried out, for stellar models with electron scattering as main source of opacity, χ0 should vary nearly in- versely proportional to the mass. Adopting with Henyey, Le- 6 6 Levier, and Levée the value τ0 =: 3 X 10 years for m = 3 mQ, it follows that for ζ Persei tc, as given before, is much shorter than the expansion age of the association. We may thus conclude that the hypothesis which makes the formation of ζ Per sei simul- taneous with the beginning of the expansion of the association is not corroborated by the estimate of the lifetime of the cBl stars at high galactic latitude. 1 W. W. Morgan, A. D. Code, and A. E. Whitford, Ap. J. Supplements, 2,41,1955 (No. 14). 2 P. C. Keenan and W. W. Morgan, "Classification of Stellar Spectra," Astrophysics, J. A. Hynek, ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1951), p. 12. 3 R. E. Wilson, General Catalogue of Stellar Radial Velocities (Wash- ington : Carnegie Institution of Washington Pub. No. 601, 1953). 4J. H. Oort and A. J. J. van Woerkom, B.A.N., 9, 185, 1941 (No. 338). s J. H. Oort, B.A.N., 12,177,1954 (No. -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Popular Names of Deep Sky (Galaxies,Nebulae and Clusters) Viciana’S List

POPULAR NAMES OF DEEP SKY (GALAXIES,NEBULAE AND CLUSTERS) VICIANA’S LIST 2ª version August 2014 There isn’t any astronomical guide or star chart without a list of popular names of deep sky objects. Given the huge amount of celestial bodies labeled only with a number, the popular names given to them serve as a friendly anchor in a broad and complicated science such as Astronomy The origin of these names is varied. Some of them come from mythology (Pleiades); others from their discoverer; some describe their shape or singularities; (for instance, a rotten egg, because of its odor); and others belong to a constellation (Great Orion Nebula); etc. The real popular names of celestial bodies are those that for some special characteristic, have been inspired by the imagination of astronomers and amateurs. The most complete list is proposed by SEDS (Students for the Exploration and Development of Space). Other sources that have been used to produce this illustrated dictionary are AstroSurf, Wikipedia, Astronomy Picture of the Day, Skymap computer program, Cartes du ciel and a large bibliography of THE NAMES OF THE UNIVERSE. If you know other name of popular deep sky objects and you think it is important to include them in the popular names’ list, please send it to [email protected] with at least three references from different websites. If you have a good photo of some of the deep sky objects, please send it with standard technical specifications and an optional comment. It will be published in the names of the Universe blog. It could also be included in the ILLUSTRATED DICTIONARY OF POPULAR NAMES OF DEEP SKY. -

The Astrology of Space

The Astrology of Space 1 The Astrology of Space The Astrology Of Space By Michael Erlewine 2 The Astrology of Space An ebook from Startypes.com 315 Marion Avenue Big Rapids, Michigan 49307 Fist published 2006 © 2006 Michael Erlewine/StarTypes.com ISBN 978-0-9794970-8-7 All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Graphics designed by Michael Erlewine Some graphic elements © 2007JupiterImages Corp. Some Photos Courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech 3 The Astrology of Space This book is dedicated to Charles A. Jayne And also to: Dr. Theodor Landscheidt John D. Kraus 4 The Astrology of Space Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................... 15 Astrophysics for Astrologers .................................. 17 Astrophysics for Astrologers .................................. 22 Interpreting Deep Space Points ............................. 25 Part II: The Radio Sky ............................................ 34 The Earth's Aura .................................................... 38 The Kinds of Celestial Light ................................... 39 The Types of Light ................................................. 41 Radio Frequencies ................................................. 43 Higher Frequencies ............................................... -

AUS DEM INHALT Mein Lieblingssternbild H

AUS DEM INHALT Mein Lieblingssternbild H0- Eine Magical Mystery Tour der Kosmologie Erste Erfahrungen mit der ZWO ASI2600MM pro 34. Jahrgang – 1/2021 3.- Euro Andromeda 1/21 Inhalt Editorial ................................................................................................................................ 4 Lustiges Silbenrätsel - Auflösung ..................................................................................... 4 Der 80mm Apochromat von Explore Scientific ........................................................... 5 Mein Lieblingssternbild ...................................................................................................... 7 Perseverance, der Mars und das Geheimnis von Elon? ............................................... 10 Stephans Quintett .............................................................................................................. 11 Sternfreunde intern ........................................................................................................... 11 Die habitable Zone und superhabitable Planeten Teil 1............................................... 12 Erste Erfahrungen mit der ZWO ASI2600MM pro Astrokamera ............................. 16 NGC 1579 - „Nördlicher Trifidnebel“ - Angaben zum Foto auf der Rückseite ..... 18 Die Große Konjunktion Jupiter / Saturn vom 21.12.2020 ........................................... 18 Die Hubble Konstante – Eine Magical Mystery Tour der Kosmologie ..................... 19 Was? Wann? Wo? ..............................................................................................................